Hong Kong Med J 2022 Apr;28(2):107–15 | Epub 31 Mar 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Surgical treatment of pelvic organ prolapse in

women aged ≥75 years in Hong Kong: a multicentre retrospective study

Daniel Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; YT Lee, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)2; Grace PY Tang, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)3; Symphorosa SC Chan, MD, FRCOG4

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Pamela Youde Nethersole

Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Prince of Margaret Hospital,

Hong Kong

3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong

Kong

4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Prince of Wales Hospital,

Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Daniel Wong (dlwhk@yahoo.com)

Abstract

Introduction: Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is

common among older women. With the increasing

lifespan and emphasis on quality of life worldwide,

older women increasingly prefer surgical treatment

for POP. We reviewed the surgical treatment of

POP in older women to characterise its safety,

effectiveness, and the type most often selected.

Methods: This multicentre, retrospective study

was conducted at four hospitals between 2013 and

2018. Included patients were aged ≥75 years and

had undergone POP surgery. We compared patient

demographic characteristics, POP severity, and

surgical outcomes between reconstructive and

obliterative surgeries; these comparisons were also

made among vaginal hysterectomy plus pelvic floor

repair (VHPFR), transvaginal mesh surgery (TVM),

vaginal hysterectomy (VH) plus colpocleisis, and

colpocleisis alone.

Results: In total, 343 patients were included; 84.3%

and 15.7% underwent reconstructive and obliterative

surgeries, respectively. Overall, 246 (71.7%), 43

(12.5%), 20 (5.8%), and 34 (9.9%) patients underwent

VHPFR, TVM, VH plus colpocleisis, and colpocleisis

alone, respectively. Patients who were older (81.9 vs

79.6 y; P=0.001), had vault prolapse (38.9% vs 3.5%;

P<0.001), and had medical co-morbidities (37%

vs 4.8%; P<0.001) chose obliterative surgery more frequently than reconstructive surgery. Obliterative

surgeries had shorter operative time (73.5 min vs

107 min; P<0.001) and fewer surgical complications

(9.3% vs 28.0%; P=0.003). Vaginal hysterectomy plus

pelvic floor repair had the highest rate of surgical

complications (most were minor), while colpocleisis

alone had the lowest rate (30.1% vs 8.8%; P=0.01).

Conclusions: Pelvic organ prolapse surgeries were safe and effective for older women. Colpocleisis may be appropriate as primary surgery for fragile older women.

New knowledge added by this study

- The most common type of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery was vaginal hysterectomy plus pelvic floor repair. Patients who were older (81.9 vs 79.6 y; P=0.001), had medical co-morbidities (37% vs 4.8%; P<0.001), had a history of pelvic floor repair surgery (13% vs 1.7%; P=0.001), and had vaginal vault prolapse (38.9% vs 3.5%; P<0.001) chose obliterative surgery more frequently than reconstructive surgery.

- Because all types of POP surgery were associated with no mortality and generally had self-limiting surgical complications, they are safe for women aged ≥75 years. However, fluid replacement should be cautiously administered in fragile patients and in patients susceptible to fluid overload.

- Colpocleisis alone had the shortest operative time (60 min; P<0.001), least blood loss (50 mL; P<0.001), and fewest surgical complications (8.8%; P=0.01). Moreover, 76.5% of procedures comprising colpocleisis alone were performed under spinal anaesthesia (P<0.001).

- All four types of POP surgeries are safe and effective for the treatment of POP in older women.

- The incidence of carcinoma of the corpus uteri (Ca corpus) was 0.3% in this study. To reduce the risk of missing Ca corpus, preoperative transvaginal ultrasound (to assess endometrial thickness) and endometrial aspiration should be considered women who plan to undergo uterine-preserving surgery.

- Comparison of vaginal hysterectomy plus colpocleisis and colpocleisis alone showed that the combined treatment had a longer operative time and greater blood loss, but a comparable rate of complications. Therefore, vaginal hysterectomy plus colpocleisis remains a valid treatment option. Both methods involving colpocleisis lead to difficulty in assessment of the cervix and uterus regardless of pathology.

- Colpocleisis alone had the shortest operative time, least blood loss, and fewest surgical complications. These excellent results suggest that colpocleisis may be appropriate as primary surgery for fragile older women who do not engage in sexual intercourse.

Introduction

The incidence of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is

reportedly near 50% and the lifetime risk of POP

requiring surgery is approximately 20%.1 2 With the

increasing lifespan and emphasis on quality of life

worldwide, older women increasingly prefer surgical

treatment, instead of vaginal pessaries, as definitive

treatment for POP.3 Surgical treatment options are

either reconstructive or obliterative. Reconstructive

surgery comprises native tissue repair (mainly

vaginal hysterectomy [VH]), pelvic floor repair, and

mesh-related repair; obliterative surgery comprises

colpocleisis with or without concomitant VH.

Older women who undergo urogynaecological

surgery have a higher surgical risk, regardless of

fragility index; they have lower risks of prolapse

recurrence and repeated surgery.4 Although the

World Health Organization has defined old age as

≥65 years,5 a threshold of ≥75 years may be more

appropriate for older women in terms of fragility and

need for care. A previous Hospital Authority ageing

projection6 indicated that the number of individuals

aged 75 to 84 years will substantially increase in

Hong Kong, while the numbers of individuals aged

≥85 years or ≤74 years will remain comparatively

stable. A threshold of ≥75 years for geriatric medicine

may be reasonable because most chronic, complex disabling disease occurs among individuals in this age-group.7

To our knowledge, despite the increasing

number of women aged ≥75 years and the need for

surgical treatment of POP among these individuals,

there is limited evidence regarding the risks and

benefits of the available surgical options. This

multicentre, retrospective study was performed

to review the surgical treatment of POP in women

aged ≥75 years; we aimed to characterise its safety,

effectiveness, and the type most often selected. We

hope that the findings will help clinicians to counsel

older women with POP who are considering surgical

treatment.

Methods

Patients

This multicentre, retrospective cohort study was

conducted at Kwong Wah Hospital, Pamela Youde

Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Princess Margaret

Hospital, and Prince of Wales Hospital. We included

patients aged ≥75 years, all of whom underwent

surgical treatment of POP in one of the above four

gynaecological units between 2013 and 2018. We

reviewed patient information from the Clinical

Data Analysis and Reporting System and Clinical

Medical System; for patients with incomplete data

in the Clinical Medical System, we reviewed paper-based

medical records. Ethical approvals were

obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of

all four Clusters including Hong Kong East Cluster,

Kowloon Central Cluster, Kowloon West Cluster

and New Territories East Cluster.

Examination and treatment selection

Demographic data and symptoms of prolapse

were collected during each patient’s first visit

to a participating gynaecology unit. Physical

examinations were conducted to confirm POP,

stage of prolapse, and the compartments involved;

all examinations were performed using the

International Continence Society Pelvic Organ

Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) staging system.7

Patients were offered vaginal pessary management

or surgical treatment. Patients who opted for surgical

treatment were scheduled for surgery with or without

a trial period of vaginal pessary management.

Preoperative urodynamics studies were performed if

indicated. During the preoperative assessment, each

patient underwent a comprehensive evaluation that

included patient-reported symptoms of prolapse,

as well as urinary, intestinal, and sexual statuses;

they also underwent prolapse assessment using

POP-Q staging. Thorough counselling was provided

regarding reconstructive and obliterative treatment

options, including a discussion of the potential

benefits and risks of both procedures, as well as the need for concomitant VH or mid-urethral sling transobturator tape (TVT-O) for urodynamic stress incontinence.

Surgical procedures

Reconstructive procedures involved native tissue

repair and mesh-related surgery. Native tissue repair

mainly comprised vaginal hysterectomy followed

by pelvic floor repair (VHPFR; eg, anterior and/or

posterior colporrhaphy). In addition, sacrospinous

ligament fixation was performed for stage ≥III

uterine prolapse or vaginal vault prolapse. Patients

with stage ≥III anterior compartment prolapse were

offered anterior vaginal mesh repair. Obliterative

surgery comprised colpocleisis with or without

concomitant VH. Anterior vaginal mesh repair

and colpocleisis were only offered to patients who

were sexually inactive before surgery or agreed not

to engage in sexual intercourse. Combinations of

concomitant procedures were performed in the

following order, using only the procedures selected

by each patient and their surgeon: VH, mesh

placement and sacrospinous fixation, native tissue

repair, and TVT-O placement. All native tissue

repair procedures were performed or supervised by

a gynaecological specialist; all sacrospinous ligament

fixation or anterior vaginal mesh repair procedures

were performed or supervised by urogynaecologists.

One dose of prophylactic intravenous antibiotic

was administered during anaesthesia induction.

In patients who underwent reconstructive surgery,

one piece of vaginal gauze was placed to achieve

haemostasis for 1 day. A Foley catheter was placed

to ensure urinary drainage for 1 to 2 days according

to the procedures used in each unit. Operative

time, intra-operative blood loss, perioperative

complications, and postoperative adverse events

were recorded. Postoperative fever was defined as

≥2 readings of temperature ≥38°C with no positive

culture or identifiable cause. A diagnosis of urinary

tract infection was made on the basis of positive

midstream urine culture results. A diagnosis of

urinary retention was made when a patient could not

void and required catheterisation. All instances of

postoperative haematoma were diagnosed by imaging

(ultrasound or computed tomography scan). When

available, pathology reports were also reviewed.

Postoperative assessments

All patients underwent the same postoperative

assessment, which was structured using a

standardised datasheet. Follow-up visits were

scheduled at 6 to 12 weeks and 1 year after surgery,

then annually until 5 years after surgery. Each follow-up

visit evaluation included assessments of urinary

and intestinal function; symptoms of prolapse,

vaginal pain and dyspareunia; and symptoms of mesh erosion. Vaginal examinations and POP-Q

assessments were performed to identify instances

of POP recurrence or mesh-related complications,

in accordance with the recommendations of

the International Continence Society and the

International Urogynecological Association.9

Prolapse recurrence was defined as the presence of

subjective symptoms of prolapse or a POP-Q stage

of ≥II in a clinical examination.

Statistical analysis

We compared patient demographic characteristics,

POP severity, and surgical outcomes between two

groups: reconstructive and obliterative surgeries.

These comparisons were also made among four

subgroups: VHPFR, transvaginal mesh surgery

(TVM), VH plus colpocleisis, and colpocleisis alone.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

(Windows version 26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY],

United States). Descriptive statistics were used to

summarise demographic and clinical characteristics.

Continuous variables were expressed as mean

(standard deviation) or median (interquartile

range); they were analysed by independent-samples

t tests or the Mann-Whitney U test (comparison

of two groups)/one-way analysis of variance or

Kruskal–Wallis H test (comparison of ≥3 groups),

depending on the normality of the data assessed by

Shaprio–Wilk test. Categorical data were expressed

as numbers and percentages; the Chi squared test

and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical

data analysis. A P value of <0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

Results

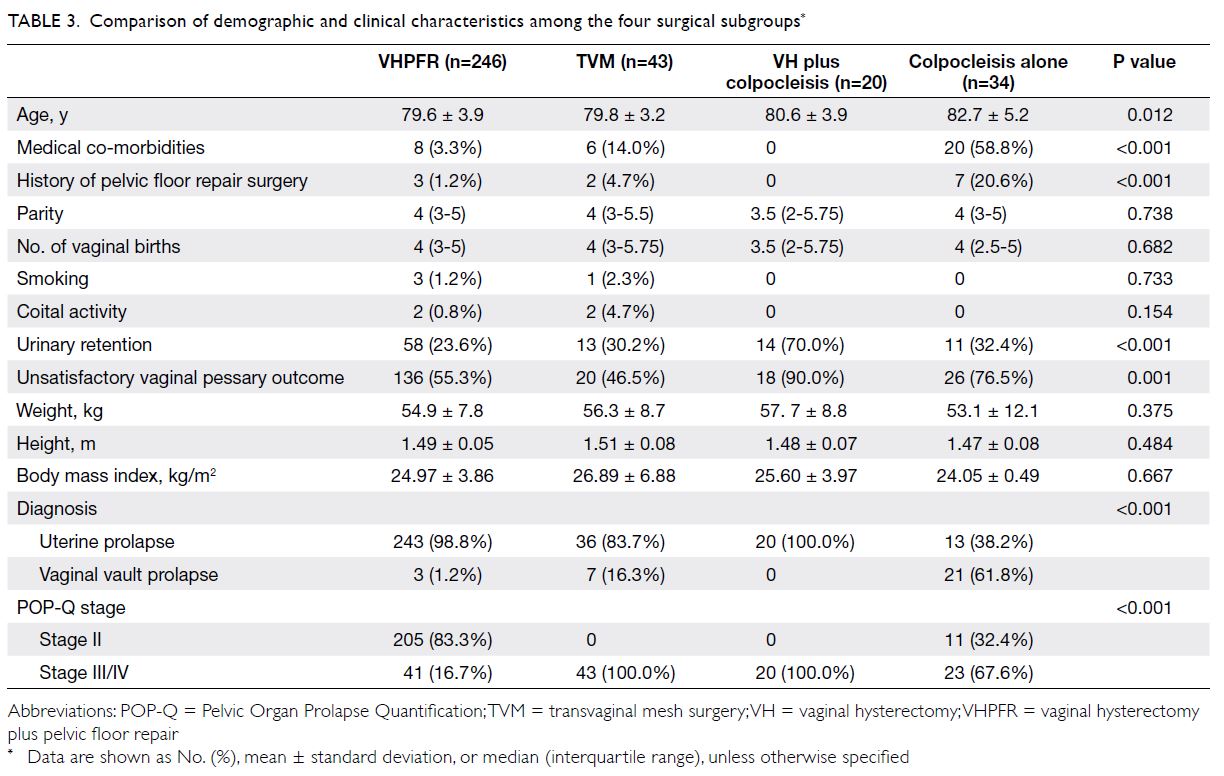

In total, 343 patients underwent surgery for POP

from 2013 to 2018 in the study hospitals. The types

of surgical treatment at each hospital are shown

in Table 1. Vaginal hysterectomy plus pelvic floor repair procedures were evenly distributed among all

four hospitals. However, 93% of TVM procedures,

95% of VH plus colpocleisis procedures, and 50%

of procedures comprising colpocleisis alone were

performed in Prince of Wales Hospital, Princess

Margaret Hospital, and Pamela Youde Nethersole

Eastern Hospital, respectively.

Table 1. Type of surgical treatment performed in women aged ≥75 years with pelvic organ prolapse in the study hospitals

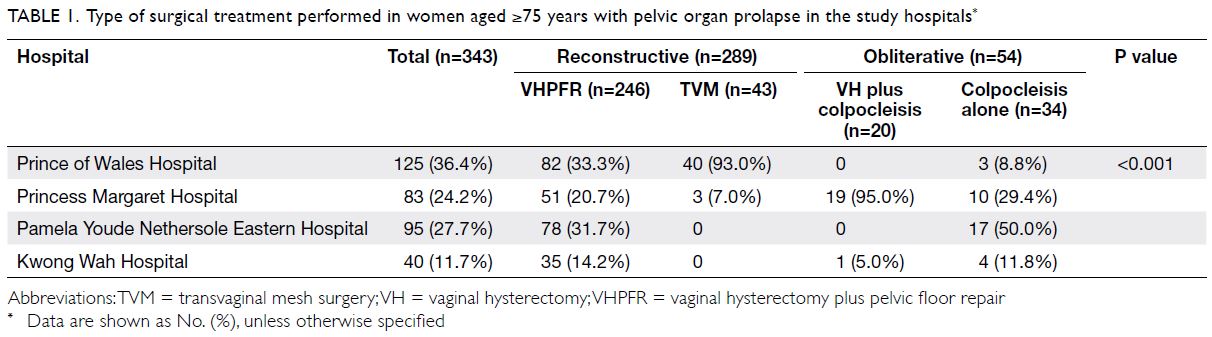

Among the 343 patients, 216 (63%), 90 (26.2%),

and 37 (10.8%) had stages II, III, and IV POP,

respectively (Table 2). Furthermore, 289 (84.3%)

patients underwent reconstructive surgery and

54 (15.7%) patients underwent obliterative surgery.

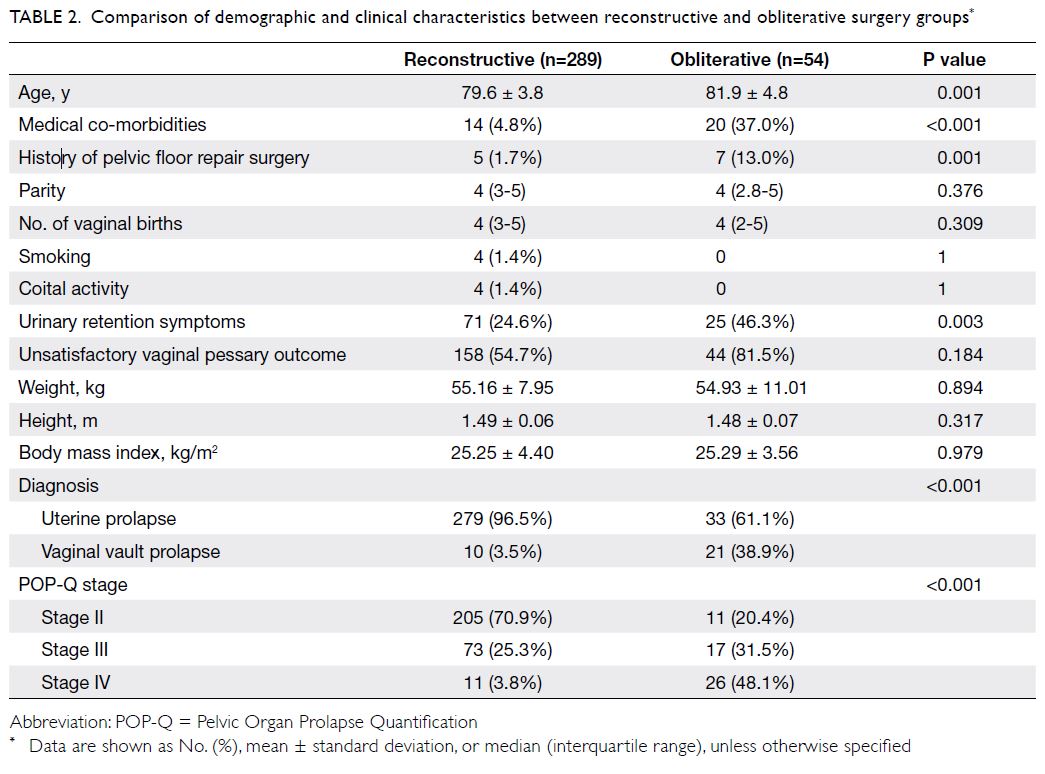

Of the 289 reconstructive surgeries, 246 (71.7%) were

native tissue repair procedures (mainly VHPFR),

while 43 (12.5%) were TVM (36 had concomitant

VH); among the 54 obliterative surgeries, 20 (5.8%)

were colpocleisis plus VH, while the remaining

34 (9.9%) were colpocleisis alone (Table 3).

Table 2. Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics between reconstructive and obliterative surgery groups

Table 2 compares demographic and clinical

characteristics between the reconstructive and

obliterative surgery groups. Patients with more

advanced age chose obliterative surgery, rather than

reconstructive surgery (81.9 vs 79.6 y; P=0.001).

Other variables including parity, number of vaginal

births, number of instrumental deliveries, body mass

index, smoking, and coital activity were comparable

between the two groups.

More patients with vaginal vault prolapse opted

for obliterative surgery, rather than reconstructive surgery (38.9% vs 3.5%; P<0.001) [Table 2]. The

difference was more striking when the colpocleisis

alone group was compared with all patients who

underwent reconstructive surgery (61.8%; P<0.001)

[Table 3]. Moreover, the number of patients who had

medical co-morbidities (eg, hypertension, diabetes

mellitus, heart disease, or history of stroke) was

greater in the obliterative surgery group than in the

reconstructive surgery group (37% vs 4.8%, P<0.001)

[Table 2].

Concerning patients with stage III/IV POP, more patients underwent TVM, rather than VHPFR,

in the reconstructive surgery group (100% vs 16.7%;

P<0.001); in the obliterative surgery group, more

patients with stage III/IV POP underwent VH plus

colpocleisis, rather than colpocleisis alone (100% vs

67.6%; P<0.004) [Table 3].

One case of carcinoma of the corpus uteri

(Ca corpus) was confirmed from the pathology report

of a patient who underwent VH. Thus, the incidence

of Ca corpus was 0.3% (1/312). The affected woman

was an asymptomatic patient in the TVM group; she

had incidental findings of endometrial thickening

during preoperative assessment. The results of

endometrial aspiration could not exclude a diagnosis

of hyperplasia. The patient underwent postoperative

contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the

abdomen and pelvis 2 months after surgery; there

were no signs of distant metastasis. After detailed

counselling, the patient refused further surgery or

adjuvant therapy. For 25 months of follow-up, the

patient’s cancer has remained in remission.

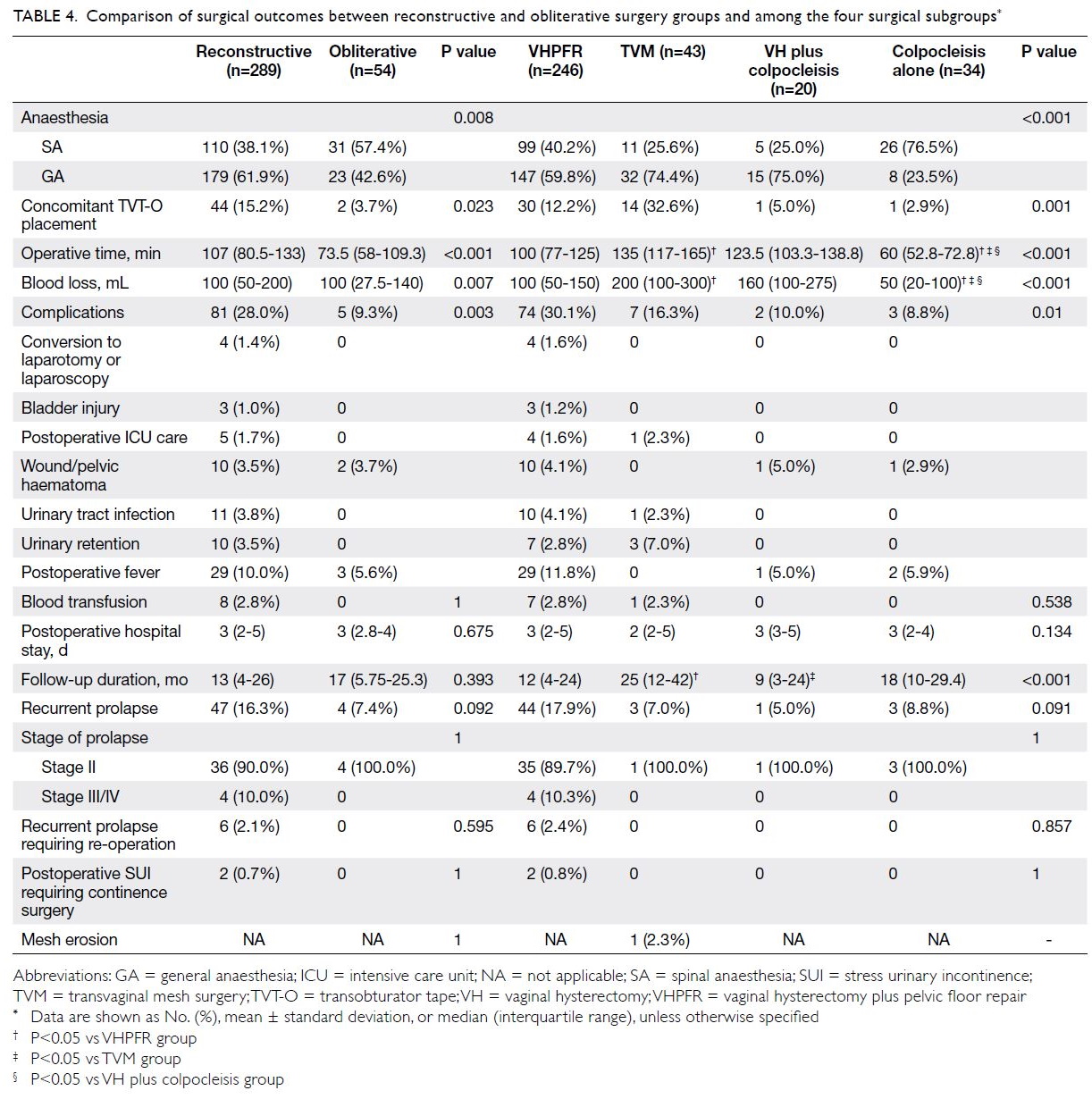

Table 4 shows surgical outcomes in both

groups and all subgroups. Compared with

obliterative surgeries, fewer reconstructive surgeries

were performed under spinal anaesthesia (57.4%

vs 38.1%; P=0.008). Notably, 76.5% of procedures comprising colpocleisis alone were performed under

spinal anaesthesia (P<0.001). Obliterative surgeries

had a shorter operative time (73.5 min vs 107 min;

P<0.001) and fewer surgical complications (9.3% vs

28.0%; P=0.003) than did reconstructive surgeries.

Among the four subgroups, colpocleisis alone had

the shortest operative time (60 min; P<0.001) and

least blood loss (50 mL; P<0.001).

Table 4. Comparison of surgical outcomes between reconstructive and obliterative surgery groups and among the four surgical subgroups

Analysis of surgical complications (Table 4)

showed that the VHPFR group had the highest

intra- and peri-operative complication rate (30.1%;

P=0.01), compared with the other subgroups. In

the VHPFR group, four (1.6%) patients required

conversion to laparoscopy/laparotomy (two had

dense adhesion, one had large uterine size, and one

had difficulty achieving haemostasis). There were

three (1.2%) bladder injuries; all underwent primary

repair with good recovery and did not experience

long-term consequences. Four (1.6%) patients in the

VHPFR group required intensive care unit (ICU)

admission after surgery (one had fluid overload, one

had respiratory acidosis, one had cardiac problems,

and one had metabolic acidosis). In all, 29 (11.8%)

patients had fever of unknown cause; 90% of them

resolved by oral antibiotics. Ten (4.1%) patients had

postoperative wound or pelvic haematoma, and 10 (4.1%) patients had urinary tract infection. In

the TVM group, one (2.3%) patient required ICU

admission because of fluid overload, while three (7%)

patients had urinary retention after surgery. The VH

plus colpocleisis and colpocleisis alone groups both

included one patient with wound haematoma. In

the TVM group, 32.6% of patients had concomitant

TVT-O placement; 12.2%, 5%, and 2.9% of patients

had concomitant TVT-O placement in the VHPFR,

VH plus colpocleisis, and colpocleisis alone groups, respectively (P=0.001) [Table 4].

The median durations of follow-up were 13

and 17 months in the reconstructive and obliterative

surgery groups, respectively (Table 4). The TVM

group had a significantly longer median follow-up

duration (25 months; P<0.001); this was consistent

with the need to monitor any mesh complications.

There was only one patient was lost to follow-up

throughout the study period. Although there tended

to be fewer instances of recurrence in the obliterative surgery group than in the reconstructive surgery

group (7.4% vs 16.3%; P=0.092), the difference was

not statistically significant. There also tended to be

a higher rate of prolapse recurrence in the VHPFR

group than in the TVM, VH plus colpocleisis, or

colpocleisis alone groups (VHPFR 18%, TVM 7%,

VH plus colpocleisis 5%, and colpocleisis alone

8.8%), but this trend was not statistically significant

(P=0.091). Finally, few patients in each group

underwent surgery for prolapse recurrence or stress

urinary incontinence after surgery.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first multicentre

retrospective study in Hong Kong concerning

POP surgery for women aged ≥75 years. Overall

analysis of demographic characteristics indicated

that most patients underwent VHPFR because the

largest proportion of patients had stage II POP.

Most patients were sexually inactive (only four of

343 patients reported sexual activity), multiparous

(median of four births overall), and had a history

of exclusively vaginal delivery. The mean body

mass index overall was 25.3 kg/m2. Compared with

reconstructive surgery, obliterative surgery was

more frequently selected by patients who were

older, had medical co-morbidities, had a history of

pelvic floor repair surgery, and had vaginal vault

prolapse.

In this study, we found that surgical treatment

was a safe option for older women who sought

to improve their quality of life. The postoperative

mortality rate was zero, consistent with the low

mortality rate 4.1% in a previous study.4 Notably,

prior studies10 11 in Chinese populations suggested

that poor quality of life and complications associated

with vaginal pessary management lead to an

increased likelihood of surgical treatment. In our

study, over 80% of patients in the obliterative surgery

group had an unsatisfactory vaginal pessary outcome;

nearly half of the patients also had urinary retention.

Therefore, it is reasonable that these patients chose

POP surgery, despite their advanced age.

In studies from other countries, the reported

rates of surgical complications associated with POP

surgery in women aged ≥75 years were 30% to 40%.12 13

Although the VHPFR group had the highest rate of

surgical complications among all subgroups in the

present study, the rate of 30.1% was comparable to

the rates in studies from other countries. However,

1.7% of patients in the reconstructive surgery group

were admitted to the ICU after surgery; this was

higher than the reported rate of 0.45% in a large

cohort study with a mean patient age of 62.7 years.14

Because older women are more likely to experience

fluid overload—it was present in 40% of the patients

who required postoperative ICU care in our study—perioperative fluid replacement should be cautiously administered.

Patients in the obliterative surgery group had

fewer surgical complications than did patients in

the reconstructive surgery group. When the four

types of surgeries were compared, the proportion

of surgeries performed under spinal anaesthesia

was greatest for procedures comprising colpocleisis

alone; these procedures also had the least blood loss,

shortest operative time, and fewest complications.

Furthermore, the hospital stay in the colpocleisis

alone group was comparable with the lengths in other

groups, although significantly larger proportions of

patients in the colpocleisis alone group had medical

co-morbidities and were older.

Theoretically, colpocleisis with concomitant

VH is superior to colpocleisis alone because it

avoids the possibility of missing Ca corpus during

surgery or later in the patient’s life15 16; however,

it is associated with a longer operative time and

increased blood loss.17 18 Our results were consistent

with the findings in previous studies from other

countries. Patients aged ≥75 years are beyond the

peak incidence of Ca corpus: according to the Hong

Kong Cancer Registry, the median age of patients

with Ca corpus is 55 years.19 In the present study, one

patient in the TVM group had Ca corpus; thus, the

rate of incidental malignancy was 0.3%, which was

comparable to the rate of 0.26% previously reported

in Hong Kong.20 Currently, pelvic ultrasound is not

a routine component of preoperative assessment. To

reduce the risk of missing Ca corpus, preoperative

transvaginal ultrasound (to assess endometrial

thickness) and endometrial aspiration should be

considered in women who have abnormal vaginal

bleeding or plan to undergo uterine-preserving

surgery.20

Although TVM is a more complex surgery

than VHPFR, the rate of perioperative surgical

complications was lower in the TVM group; hospital

stays were comparable between the two groups.

However, the operative time was longer and blood

loss was greater in the TVM group. Compared

with patients in the VHPFR group, patients in the

TVM group had a lower rate of POP recurrence (all

recurrences occurred in patients with stage III/IV

POP) and a significantly longer follow-up duration.

The mesh erosion rate in this study (2.3%) was

lower than in another study in Hong Kong (8.9%),

which had a longer follow-up duration of 40 months

and included younger patients.21 When proper

counselling is provided, TVM is a safe option for

healthier patients with stage III/IV POP because

stage III/IV POP is a risk factor for recurrence.22

Strengths and limitations

Notable strengths of this study included its multicentre design and focus on POP surgery among

older women in the Hong Kong Chinese population,

which has not been previously explored. Patients in

this study included all women aged ≥75 years who

underwent POP surgery in a 6-year period at four

hospitals; these hospitals are jointly accredited as

a single urogynaecological training centre under

the Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists, and they have extensive experience

performing all types of POP surgery (Table 1).

Furthermore, the electronic medical record system

of the Hospital Authority facilitated complete data

collection and retrieval. However, there were a few

limitations in this study. First, it was a retrospective

study. Second, we did not perform quality of life

assessment or investigate the presence of guilt

concerning colpocleisis surgery. Because few patients

reported sexual activity before surgery, we presume

that most older women in Hong Kong would not

regret the selection of colpocleisis because of its

effects on sexual activity. Third, although the median

follow-up period was <18 months, it may have been

insufficient to fully characterise prolapse recurrence

and gynaecological malignancy. Finally, the levels of

independence and family support may be important

factors for older women to consider before making

any surgical decision; however, we did not have

access to such data. These factors could be examined

in future studies.

Conclusion

This multicentre retrospective study showed that

multiple types of POP surgeries were safe and

effective for women aged ≥75 years. Most surgical

complications were self-limiting and the recurrence

rate was low. The excellent results suggest that

colpocleisis may be appropriate as primary surgery

for fragile older women. These findings will facilitate

preoperative counselling for older women with POP

who are considering surgical treatment.

Author contributions

Concept or design: D Wong, SSC Chan

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: D Wong, SSC Chan.

Drafting of the article: D Wong, SSC Chan.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: D Wong, SSC Chan.

Drafting of the article: D Wong, SSC Chan.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to Ms LL Lee, Dr TH Chan and Dr CW Chu for data collection and entry.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Hong Kong East Cluster Ethics

Committee (HKECREC-2020-069), the Kowloon Central

Cluster Ethics Committee (KC/KE-20-0223/ER-2), the

Kowloon West Cluster Ethics Committee (EX-20-108[150-02]), and the New Territories East Cluster Ethics Committee

(NTEC-2020-138).

References

1. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL.

Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse

and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 1997;89:501-6. Crossref

2. Smith FJ, Holman CD, Moorin RE, Tsokos N. Lifetime risk

of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet

Gynecol 2010;116:1096-100. Crossref

3. Griebling TL. Vaginal pessaries for treatment of pelvic

organ prolapse in elderly women. Curr Opin Urol

2016;26:201-6. Crossref

4. Sung VW, Weitzen S, Sokol ER, Rardin CR, Myers DL.

Effect of patient age on increasing morbitity and mortality

following urogynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol

2006;194:1411-7. Crossref

5. World Health Organization. Global recommendations

on physical activity for health. 2010. Available from:

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241599979.

Accessed 21 Mar 2022.

6. Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government. Strategic

service framework for elderly patients. 26 April 2012.

Available from: https://www.ha.org.hk/ho/corpcomm/Strategic%20Service%20Framework/Elderly%20Patients.pdf. Accessed 21 Mar 2022.

7. Kong TK. Hospital service for the elderly in Hong Kong—present and future. J Hong Kong Geriatr Soc 1990;1:16-20.

8. Haylen BT, Maher CF, Barber MD, et al. An International

Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International

Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology

for female pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Int Urogynecol J

2016;27:165-94. Crossref

9. Toozs-Hobson P, Freeman R, Barber M, et al. An

International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the

terminology for reporting outcomes of surgical procedures

for pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 2012;23:527-35. Crossref

10. Chan SS, Cheung RY, Yiu AK, et al. Chinese validation

of pelvic floor distress inventory and pelvic floor impact

questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J 2011;22:1305-12. Crossref

11. Chan SS, Cheung RY, Yiu KW, Lee LL, Pang AW,

Chung TK. Symptoms, quality of life, and factors affecting

women’s treatment decisions regarding pelvic organ

prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 2012;23:1027-33. Crossref

12. Friedman WH, Gallup DG, Burke JJ 2nd, Meister EA,

Hoskins WJ. Outcomes of octogenarians and

nonagenarians in elective major gynecologic surgery. Am

J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:547-52. Crossref

13. Stepp KJ, Barber MD, Yoo EH, Whiteside JL, Paraiso MF,

Walters MD. Incidence of perioperative complications of

urogynecologic surgery in elderly women. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2005;192:1630-6. Crossref

14. Mairesse S, Chazard E, Giraudet G, Cosson M, Bartolo S.

Complications and reoperation after pelvic organ prolapse,

impact of hysterectomy, surgical approach and surgeon

experience. Int Urogynecol J 2020;31:1755-61. Crossref

15. Elkattah R, Brooks A, Huffaker RK. Gynecologic

malignancies post-lefort colpocleisis. Case Rep Obstet

Gynecol 2014;2014:846745. Crossref

16. Frick AC, Walters MD, Larkin KS, Barber MD. Risk of

unanticipated abnormal gynecologic pathology at the time

of hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2010;202:507.e1-4. Crossref

17. FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Siddique S, Thompson P,

Zyczynski H, Ann Weber for the Pelvic Floor Disorders

Network. Colpocleisis: a review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic

Floor Dysfunct 2006;17:261-71. Crossref

18. Bochenska K, Leader-Cramer A, Mueller M, Davé B,

Alverdy A, Kenton K. Perioperative complications following colpocleisis with and without concomitant

vaginal hysterectomy. Int Urogynecol J 2017;28:1671-5.Crossref

19. Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital Authority, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Cancer in 2018. Available from:

https://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/pdf/factsheet/2018/corpus_2018.pdf. Accessed 29 Dec 2020.

20. Wan OY, Cheung RY, Chan SS, Chung TK. Risk of

malignancy in women who underwent hysterectomy for

uterine prolapse. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2013;53:190-6. Crossref

21. Wan OY, Chan SS, Cheung RY, Chung TK. Mesh-related

complications from reconstructive surgery for pelvic organ

prolapse in Chinese patients in Hong Kong. Hong Kong

Med J 2018;24:369-77. Crossref

22. Friedman T, Eslick GD, Dietz HP. Risk factors for prolapse

recurrence: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int

Urogynecol J 2018;29:13-21. Crossref