Hong Kong Med J 2022 Feb;28(1):76–8 | Epub 14 Feb 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome

temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2: a case report

Gilbert T Chua, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)1 †; Joshua SC Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2 † Jaime Chung, MB, BS2; Ivan Lam, FHKCP, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2; Joyce Kwong, FHKAM (Pathology)3; Kate Leung, FRCPA, FHKAM (Pathology)3; CY Law, PhD, FHKAM (Pathology)4; CW Lam, PhD, FRCP5; Janette Kwok, PhD, FRCPA6; Patrick WK Chu, MPhil6; Elaine YL Au, FRCPA, FHKCPath7; Crystal K Lam, MB, BS7; Daniel Mak, MRCPCH, FHKAM (Paediatrics)2; NC Fong, FRCPCH2; Daniel Leung, PhD (Candidate)1; Wilfred HS Wong, PhD1; Marco HK Ho, MDM, FRCP1; Sabrina SL Tsao, MB, BS, FACC1; Christina S Wong, MRCP, FHKAM (Medicine)8; Jason C Yam, MB, BS, FCOphthHK,9; Winnie WY Tso, FHKAM (Paediatrics)1; Kelvin KW To, MD, FRCPath10; Paul KH Tam, FRCS, FRCPCH11,12Godfrey CF Chan, MD, FRCPCH1; WH Leung, MB, BS, PhD1; KY Yuen, MD, FRCPath10; Vas Novelli, FRCP, FRCPCH13,14; Nigel Klein, PhD13,14; Michael Levin, PhD, FRCPCH15; Elizabeth Whitaker, MRCPCH, PhD16; YL Lau, MD (Hon), FRCPCH1; Patrick Ip, MPH, FHKAM (Paediatrics)1; Mike YW Kwan, MRCPCH, MSc (Applied Epidemiology CUHK)2

1 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Haematology Laboratory, Department of Pathology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

4 Division of Chemical Pathology, Department of Pathology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

5 Department of Pathology, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

6 Division of Transplantation and Immunogenetics, Department of Pathology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

7 Division of Clinical Immunology, Department of Pathology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

8 Division of Dermatology, Department of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

9 Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

10 Department of Microbiology, Carol Yu Centre for Infection, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

11 Division of Paediatric Surgery, Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

12 Dr Li Dak-Sum Research Centre, The University of Hong Kong–Karolinska Institutet Collaboration in Regenerative Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

13 Department of Paediatric Infectious Diseases, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, United Kingdom

14 Institute of Child Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom

15 Section of Paediatrics, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

16 Paediatric Infectious Diseases Department, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom

† Co-first authors

Corresponding author: Dr Mike YW Kwan (kwanyw1@ha.org.hk)

Case report

A 10-year-old ethnic-Russian boy was confirmed to

have severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

2 (SARS-CoV-2) during the second wave of the

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak

in Hong Kong.1 He had a past medical history of

coarctation of the aorta with corrective surgery

performed at age 2 months. He returned from Russia

on 6 June 2020 and his first deep throat saliva specimen

saved on arrival at Hong Kong International Airport

tested negative for SARS-CoV-2. Four days later, he

developed fever, malaise, and headache. On 13 June

2021, he was admitted to our Paediatric Infectious

Disease Unit and a new deep throat saliva specimen

was positive for SARS-CoV-2. He did not require

oxygen during his hospital stay. He was discharged

from the hospital after being tested positive for

SARS-CoV-2 anti-nucleoprotein immunoglobulin G

antibodies 17 days after admission. This complied with the discharge criteria set by the Department

of Health, the Government of Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region.1

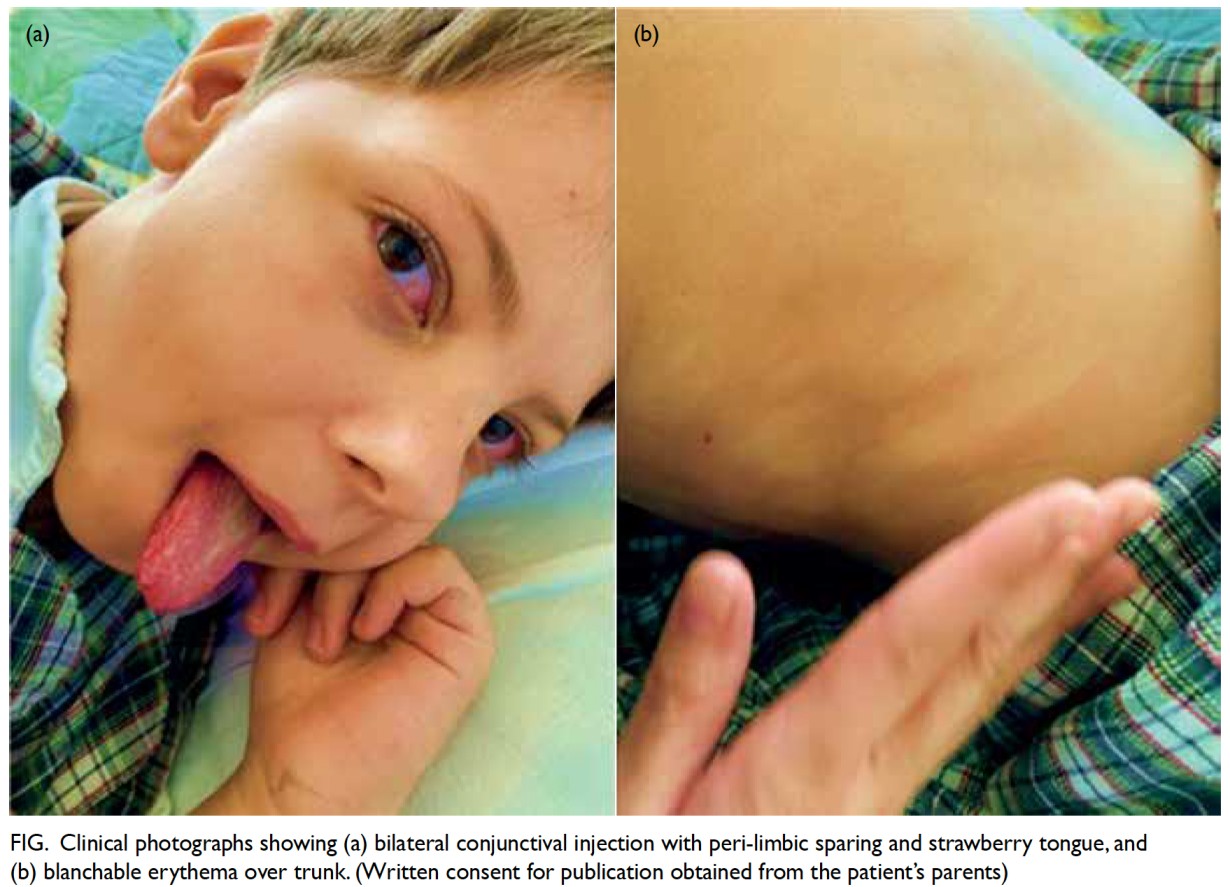

On 16 July, 16 days after being discharged, he

returned to our Paediatric Infectious Disease Unit

with a 2-day history of high fever and right cervical

tender lymphadenopathy. Repeat nasal pharyngeal

swab for SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction

was negative. He was presumed to have bacterial

lymphadenitis and was prescribed intravenous

antibiotics but symptoms progressed. Ultrasound

of the neck showed evidence of lymphadenitis

but no signs of abscess formation. His fever and

lymphadenitis persisted for 5 days and he also

developed bilateral non-purulent conjunctivitis

with peri-limbic sparing, erythematous and cracked

lips, strawberry tongue and blanchable erythema

over the trunk (Fig). Serial blood tests showed mild

thrombocytopenia (trough 110 × 109/L), and raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (peak 60 mm/Hr),

C-reactive protein (peak 102 mg/L; range, <5.0),

lactate dehydrogenase (270 U/L; range, <270),

ferritin (1568 pmol/L; range, 31-279), highly sensitive

troponin I (peak 643 ng/L; range, <21), N-terminal

prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (peak

3213 ng/L; range, <112), and interleukin-6 (IL-6)

(peak 480.9 pg/mL; range, <4). Electrocardiogram

and echocardiogram were unremarkable. His clinical

presentation was compatible with Kawasaki-like

disease. Since he had been infected with COVID-19

approximately 4 weeks previously, he was suspected to

have PIMS-TS (paediatric multisystem inflammatory

syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2).2

Other differential diagnoses were excluded but

included streptococcal and staphylococcal infection,

Epstein–Barr virus infection and infection-related

myocarditis. Owing to the rarity of PIMS-TS in

East Asia, the clinical team discussed the case with

experts from the United Kingdom who concurred

with the diagnosis. He was treated with two doses of

intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) at 2 g/kg/dose

as his fever resurged 1 day after the first dose. Fever

and other symptoms subsequently subsided after the

second dose of IVIG, and serial echocardiograms

did not reveal any coronary lesions. Whole exome

sequencing performed to look for the possibility of

an underlying monogenic immune dysregulation syndrome because of the rarity of this condition was unremarkable.

Figure. Clinical photographs showing (a) bilateral conjunctival injection with peri-limbic sparing and strawberry tongue, and (b) blanchable erythema over trunk. (Written consent for publication obtained from the patient’s parents)

Discussion

Paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome

temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 is one of the

most severe complications of COVID-19 infection

in children. It was initially described in several case

series in Europe and North America among children

who presented with Kawasaki-like illness and

were confirmed or known to have been in contact

with another SARS-CoV-2–infected individual.2 3

Kawasaki disease (KD) is most prevalent among

East Asians but rare in other parts of the world.3

On the contrary, paediatric cross-sectional clinical

studies from East Asia have reported that PIMS-TS

is rare among East Asians.1 We present the first, and

so far, the only case of PIMS-TS in China. The case

was an ethnic Russian boy who showed features of

KD approximately 4 weeks after confirmation of

SARS-CoV-2 infection. There is no consensus on the

treatment regimen at present. In our patient, IVIG

alone, instead of steroid or immunomodulators, was

effective in treating the condition.

The pathophysiology of PIMS-TS remains

uncertain. Studies have shown significant clinical

and laboratory differences between PIMS-TS and KD, despite some similarities in clinical

presentation. Patients with PIMS-TS are generally

older than those with KD (median age, 8.3-9 years vs

2.7 years).2 3 They also have a higher white blood cell

and neutrophil count and C-reactive protein, and

a greater degree of lymphopenia and anaemia and

tendency to develop thrombocytopenia in contrast

to thrombocytosis in KD. In addition, fibrinogen

and troponin levels are more elevated in PIMS-TS.2

These factors are associated with an increased risk

of intensive care admission among children with

PIMS-TS.2 These findings imply that PIMS-TS is

a different entity to KD, with a greater degree of

inflammation and myocardial injury. Studies have

shown that certain cytokines, such as IL-6, appear

to be particularly elevated in patients with PIMS-TS

and may be involved in myocardial depression.2

Studies have also suggested that life-threatening

COVID-19 pneumonia may be associated with

monogenic inborn errors of immunity related

to type 1 interferonopathies or type 1 interferon

neutralising antibodies.4 Certain human leukocyte

antigens, which are prevalent in East Asians but

not Caucasians, have been associated with KD.4

However, no genes have been identified to cause

PIMS-TS. Future studies will continue to explore the

genetic factors related to PIMS-TS and the possible

associated leukocyte antigen that explains the ethnic

differences in PIMS-TS prevalence.

The treatment for PIMS-TS is similar to that for

KD. A recent observational study demonstrated that

patients who received IVIG and methylprednisolone

together were less likely to require second-line

biological agents, and were at lower risk of secondary

acute left ventricular dysfunction and need for

haemodynamic support with a shorter length of stay

in the intensive care unit.5 Interleukin-1 and IL-6

receptor monoclonal antibodies have been used as

second-line biological agents and have been shown

to achieve remission when first-line therapies fail.2 5

Short-term outcomes of PIMS-TS are generally good.

Immediate cardiac complications include coronary

abnormalities, transient valvular regurgitation and

myocardial dysfunction.2 The majority of patients

recover without sequelae, but mortality has been

reported.2 Data on the long-term outcomes of

PIMS-TS are lacking.

The PIMS-TS remains a rare disease among

East Asian patients.1 Nevertheless, frontline

paediatricians in East Asia should remain vigilant

when looking after ethnic non-East Asian children

with COVID-19 infection in case they develop

PIMS-TS after their initial recovery. Paediatricians

should advise parents about the symptoms and signs of PIMS-TS so that timely medical consultation can be sought.

Author contributions

Concept or design: GT Chua, JSC Wong, P Ip, MYW Kwan.

Acquisition of data: J Chung, I Lam, J Kwong, K Leung, CY Law, CW Lam, J Kwok, PWK Chu, EYL Au, CK Lam, MYW Kwan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: D Mak, NC Fong, D Leung, WHS Wong, MHK Ho, SSL Tsao, CS Wong, JC Yam, WWY Tso, KKW To, PKH Tam, GCF Chan, WH Leung, KY Yuen, V Novelli, N Klein, M Levin, E Whitaker, YL Lau.

Drafting of the manuscript: GT Chua, JSC Wong, I Lam, J Chung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: J Chung, I Lam, J Kwong, K Leung, CY Law, CW Lam, J Kwok, PWK Chu, EYL Au, CK Lam, MYW Kwan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: D Mak, NC Fong, D Leung, WHS Wong, MHK Ho, SSL Tsao, CS Wong, JC Yam, WWY Tso, KKW To, PKH Tam, GCF Chan, WH Leung, KY Yuen, V Novelli, N Klein, M Levin, E Whitaker, YL Lau.

Drafting of the manuscript: GT Chua, JSC Wong, I Lam, J Chung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This work was supported by the Collaborative Research Fund

(CRF) 2020/21 and One-off CRF Coronavirus and Novel

Infectious Diseases Research Exercises (Ref: C7149-20G).

The funding source was not involved in the study design,

collection, analysis or interpretation of data; in the writing of

the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript

for publication.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the parents of the patient provided informed

consent for the treatment and procedures.

References

1. Chua GT, Wong JS, Lam I, et al. Clinical characteristics and

transmission of COVID-19 in children and youths during

3 waves of outbreaks in Hong Kong. JAMA Netw Open

2021;4:e218824. Crossref

2. Whittaker E, Bamford A, Kenny J, et al. Clinical

characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric

inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated

with SARS-CoV-2. JAMA 2020;324:259-69. Crossref

3. To KK, Chua GT, Kwok KL, et al. False-positive SARS-CoV-2

serology in 3 children with Kawasaki disease. Diagn

Microbiol Infect Dis 2020;98:115141. Crossref

4. Sancho-Shimizu V, Brodin P, Cobat A, et al. SARS-CoV-2-r

elated MIS-C: A key to the viral and genetic causes of

Kawasaki disease? J Exp Med 2021;218:e20210446.

5. Ouldali N, Toubiana J, Antona D, et al. Association of

intravenous immunoglobulins plus methylprednisolone vs

immunoglobulins alone with course of fever in multisystem

inflammatory syndrome in children. JAMA 2021;325:855-64.Crossref