Hong Kong Med J 2022 Feb;28(1):64–72 | Epub 28 Jan 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE

Admission triage tool for adult intensive care unit

admission in Hong Kong during the COVID-19 outbreak

Gavin M Joynt, MBBCh, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)1; Anne KH Leung, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)2; CM Ho, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)3; Dominic So, MB, BS, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)4; HP Shum, MB, BS, MD5; FL Chow, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)6; Alwin WT Yeung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)7; KL Lee, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)8; Gloria KY Tang, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)9; WW Yan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)5; for the Triage Working Group of the Co-ordinating Committee (Intensive Care)

1 Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Intensive Care, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Department of Intensive Care, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong

4 Department of Intensive Care, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

5 Department of Intensive Care, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

6 Department of Intensive Care, Caritas Medical Centre, Hong Kong

7 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Ruttonjee & Tang Shiu Kin Hospitals, Hong Kong

8 Department of Intensive Care, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong

9 Department of Adult Intensive Care, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Gavin M Joynt (gavinmjoynt@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Intensive care is expensive, and the numbers of

intensive care unit (ICU) beds and trained specialist

medical staff able to provide services in Hong Kong

are limited. The most recent increase in coronavirus

disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections over July to

August 2020 resulted in more than 100 new cases

per day for a prolonged period. The increased

numbers of critically ill patients requiring ICU

admission posed a capacity challenge to ICUs across

the territory, and it may be reasonably anticipated

that should a substantially larger outbreak occur,

ICU services will be overwhelmed. Therefore,

a transparent and fair prioritisation process for

decisions regarding patient ICU admission is

urgently required. This triage tool is built on the

foundation of the existing guidelines and framework

for admission, discharge, and triage that inform

routine clinical practice in Hospital Authority ICUs,

with the aim of achieving the greatest benefit for

the greatest number of patients from the available

ICU resources. This COVID-19 Crisis Triage Tool

is expected to provide structured guidance to

frontline doctors on how to make triage decisions

should ICU resources become overwhelmed by

patients requiring ICU care, particularly during the

current COVID-19 pandemic. The triage tool takes

the form of a detailed decision aid algorithm based

on a combination of established prognostic scores,

and it should increase objectivity and transparency

in triage decision making and enhance decision-making

consistency between doctors within and across ICUs in Hong Kong. However, it remains an

aid rather than a complete substitute for the carefully

considered judgement of an experienced intensive

care clinician.

Introduction

The most recent wave of coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) infections in July to August 2020

resulted in more than 100 new cases per day in Hong

Kong for a prolonged period. The stress experienced

by individual intensive care units (ICUs) in Hong

Kong was demonstrated by the need for an unusually

large number of patient transfers between units to

maximise the available ICU capacity, despite the

implementation of surge strategies. Admission

decisions to ICUs resulting from the added pressure

for ICU beds, as well as social dimensions that were triggered by the COVID-19 outbreak, resulted

in an urgent requirement for contingencies to

inform admission triage practices in the face of

overwhelming ICU demand. Professional bodies

have recommended that triage protocols (clinical

decision support systems), rather than clinical

judgement alone, be used in triage whenever

possible,1 and that such protocols be available to

assist frontline doctors.1 2 Such protocols should be

locally relevant and prepared in advance of the need

for implementation.

This document is built on the existing Admission, Discharge, and Triage Guidelines

that inform routine clinical practice in Hospital

Authority ICUs. The purpose of this COVID-19

Crisis Triage Tool is to provide structured guidance

to frontline clinicians to assist with triage decision

making should ICU resources become overwhelmed

by patients requiring ICU care in Hong Kong.

Background

The Admission, Discharge, and Triage Guidelines

for Adult Intensive Care Services for use in day-to-day ICU operations in Hong Kong were recently

updated in an internal operations circular in 2018. A

brief summary of this guideline follows. Hong Kong

ICUs provide a high standard of intensive care by

international benchmarks.3 However, because of the

expensive nature of intensive care resources, there

are a limited number of ICU beds available in Hong

Kong. Hong Kong has approximately 7.1 critical care

beds per 100 000 population, a low number compared

with other high-income regions in Asia (Singapore:

11.4/100 000, Taiwan: 29/100 000), North America

(Canada: 12/100 000, United States: 20/100 000),

and Europe (Germany: 25/100 000, Belgium:

20/100 000).4 5 Therefore, ICU beds in Hong Kong

are generally reserved for patients with reversible

medical conditions who have reasonable prospects

of substantial recovery, and triage (prioritisation)

decisions are routinely necessary.6 7 The existing

admission and triage guidelines are designed to help

optimise the use of ICU services to achieve the largest possible benefit for the most patients within available

resources, a modified utilitarian ethical approach

that is recommended by ICU professional bodies

internationally.8 9 10 Briefly, patients who require ICU

care are referred to the ICU team for admission

screening. All ICU admission triage decisions are

supervised by a senior, experienced ICU doctor and

implemented according to individual unit policy. In

principle, all triage decisions should be based on the

patient’s medical condition and the benefits likely

to be derived from ICU admission (in comparison

with a lower level of care). Non-medical factors such

as gender, race, religion, education level, and social

status should not be considered when making triage

decisions. The existing broad-based framework

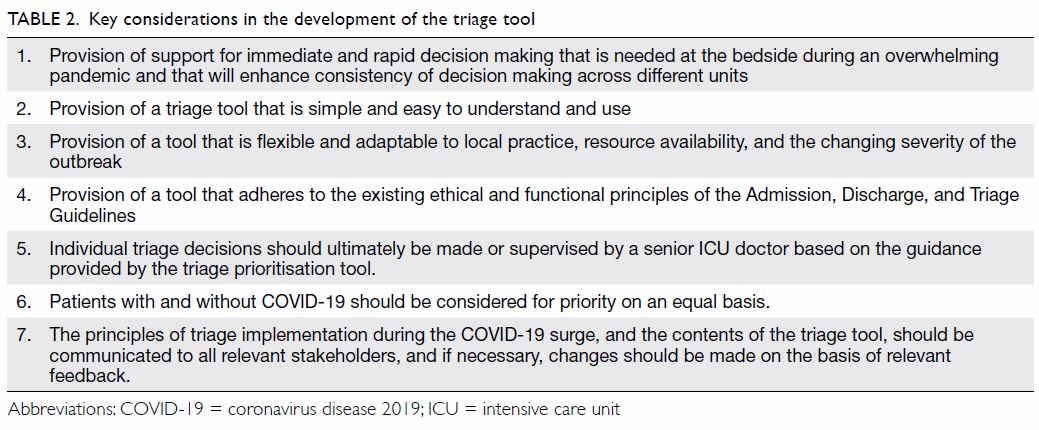

that guides individual unit policy (Fig 1) was used

to inform the relevant components of the new

COVID-19 Crisis Triage Tool.

Figure 1. Triage prioritisation is a complex clinical decision made when ICU beds are limited. Current objective scoring systems are unable to predict which patients will derive benefit from ICU admission. Nevertheless, a structured decision-making process is important to maximise transparency and improve consistency in decision making. A clinical estimation of likely benefits (comparing the outcomes of ICU admission vs the outcomes expected if the patient remained in a ward/other location) is necessary, so that patients who will benefit most from ICU admission can be given priority. This is best done by an ICU doctor who is aware of current resource pressures and is likely to be the most experienced staff member at estimating prognosis and the likely beneficial effects of ICU care. This conceptual algorithm outlines a process for making an individual triage decision. However, each decision is made on the basis of an agreed-upon triage threshold for the particular setting (ie, stricter thresholds are thus required during substantial surges in COVID-19 infections). Long-term benefits may include an assessment of expected quality of life, if appropriate.10 Before any final decision regarding ICU admission, if admission is considered potentially appropriate, patient autonomy should be respected, and therefore, the patient’s preference regarding desire for admission should be explored

Maximising existing intensive care

unit capabilities in response to a

surge of COVID-19 cases

Prioritisation for ICU admission in the form of

admission triage can only be justified once all

efforts to maximise available resources have been

exhausted. The Hospital Authority’s existing

infectious disease contingency plan dictates that

the number of available ICU beds be increased and

is based on certain key principles: first, that the

standard of intensive care should be maintained at a

standard similar to that usually provided by Hospital

Authority ICUs, and second, that infection control

procedures that provide a high level of protection

against staff cross-infection with severe acute

respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)

should be maintained. Maintaining these standards

requires the provision of appropriately trained staff

in adequate numbers. Failure to adhere to these

principles may have devastating consequences, as

occurred during the SARS outbreak in 2003.11 The

requirement to maintain these standards necessarily

results in a relatively limited surge capacity12 that may

be incapable of meeting all the demands of a large

COVID-19 transmission surge in the community.

Thus, the overall increase (68 beds) in ICU airborne

infection isolation room beds from Stage I (48 beds)

to Stage III (116 beds) will likely be insufficient.

The Hong Kong Government has plans to

construct a number of temporary community

hospitals for a potentially large surge. However, this

initiative does not include a provision for ICU beds,

and independent preparations will be required to

maximise ICU capacity. In the event that individual

hospitals need to increase ICU capacity beyond that

specified by the existing Contingency Plan Stage III

provisions, a number of key principles should be

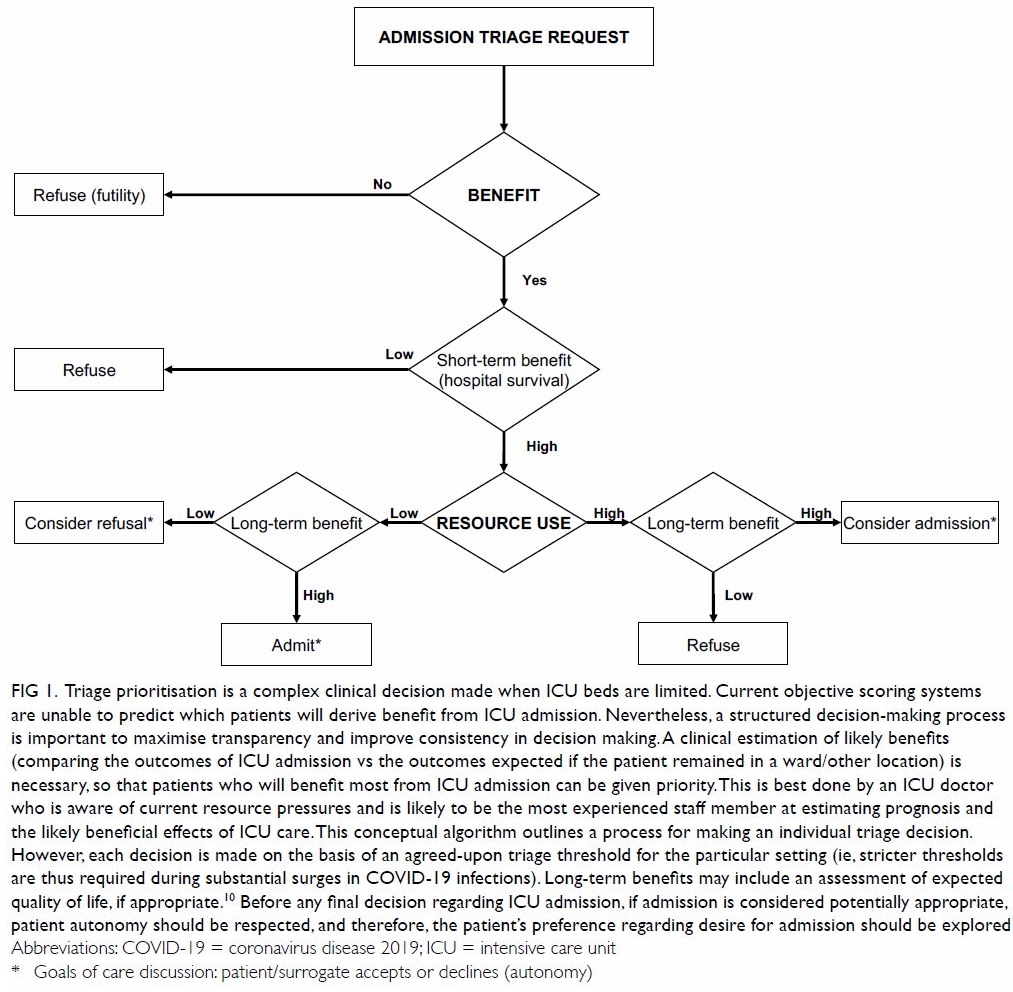

adopted (Table 1).

Table 1. Principles to be adopted for ICU bed provision and triage beyond the Stage III Contingency Plan (Crisis stage)

Methods

Despite some previous attempts, no single objective,

evidence-based triage tool in the form of a score or

combination of scores has been shown to effectively

determine appropriate ICU admission priority.13 14 15

Development of a guidance tool was thus initiated

using an iterative process in which possible

combinations of predictive scoring components

were progressively evaluated for face validity by

experienced intensive care specialists. The local

development of this triage tool to accompany the

Admission, Discharge, and Triage Guidelines for

Hong Kong (outlined above) was led by 10 senior ICU

clinical specialists who are currently practising in

ICUs in Hong Kong. The participants included at least

one representative of each of Hong Kong’s hospital

cluster regions. Additionally, each participant

routinely performs triage as a consequence of chronic

ICU bed resource limitations. An initial meeting was

held online, at which all key issues were discussed,

and a draft document of the consensus view

prepared by one author (GMJ). After circulation,

several disagreements were documented. These were

resolved by online voting, with a majority vote used

to resolve persistent disagreement. Three rounds of

online voting resulted in a finalised and universally

supported document. A decision was made to

respect and use the principles laid down in the

pre-existing triage framework but to provide further

detailed clinical guidance to frontline ICU doctors

in Hong Kong regarding COVID-19. The starting

point was to adapt and modify a recently published

COVID-19 triage prioritisation tool developed by an

international expert group.14 This tool took the form

of a decision-making algorithm based on established

ICU prognostic scoring systems that could inform

bedside decision making in the event that ICU bed

capacity becomes overwhelmed by patients with

COVID-19. Therefore, the specific aim of the triage

tool is to provide explicit and uniform guidance to all frontline doctors charged with the responsibility

of triaging ICU admissions. This guidance should

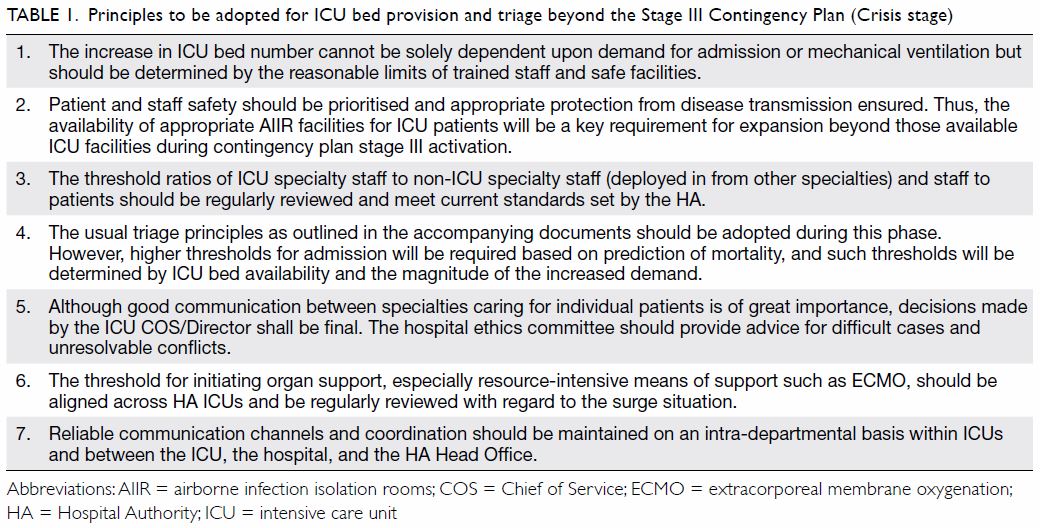

improve the objectivity and consistency of triage

decision making across Hong Kong. The

triage tool was designed to be easily understood,

rapidly implemented, and of high utility. A list of the

major considerations addressed to achieve this goal

is provided in Table 2.

Results

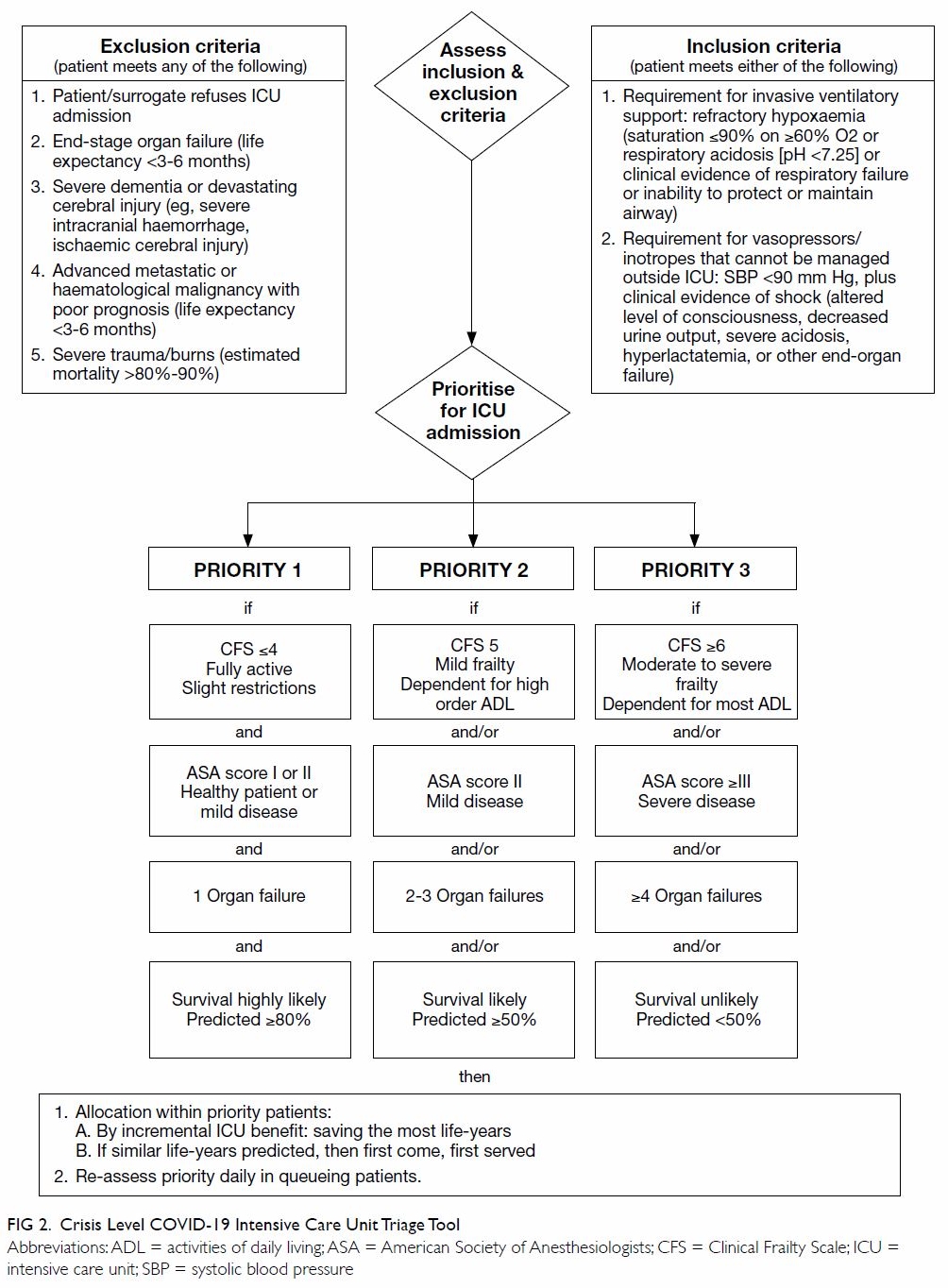

The first inclusion and exclusion criteria chosen for

the triage tool (Fig 2) were those that, when answered,

would rapidly finalise the decision without the need

to proceed further, and thus prevent excessive use of

valuable medical team time. Therefore, we created

clear clinical exclusion criteria. Patients who are too

ill to gain substantial incremental benefits from ICU

care and those who refuse ICU admission on the

basis of the perceived benefits and burdens of ICU

care are excluded.

The explicit exclusion criteria are the same

ones generally used in Hong Kong ICUs under

normal circumstances. We chose general rather than

specific diagnoses, as has been proposed previously,

as specific diagnoses require the construction of

long (but not exhaustive) lists.

The inclusion criteria are also directly

comparable with the major inclusion criteria for ICU

admission during ‘normal’ conditions: they reflect

the need to admit patients who require ICU care to

derive a survival benefit. Thus, patients who are ‘too

well’ (ie, they can be reasonably treated in the ward)

are excluded.

When a patient meets the inclusion criteria

and does not meet any exclusion criteria, they

become a potential ICU admission, and further

priority is determined. Patients are subsequently

chosen for admission based on their priority

rank, ranging from 1—high priority to 3—low

priority. A prioritisation score was developed by including variables that predict short–medium-term

mortality (3-6 months) in the first instance

and are the most compatible with the principle of

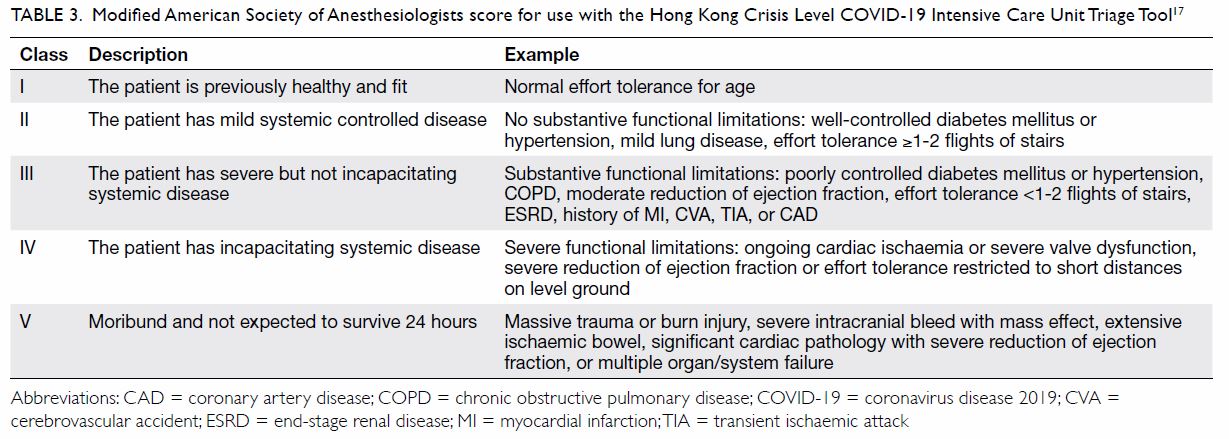

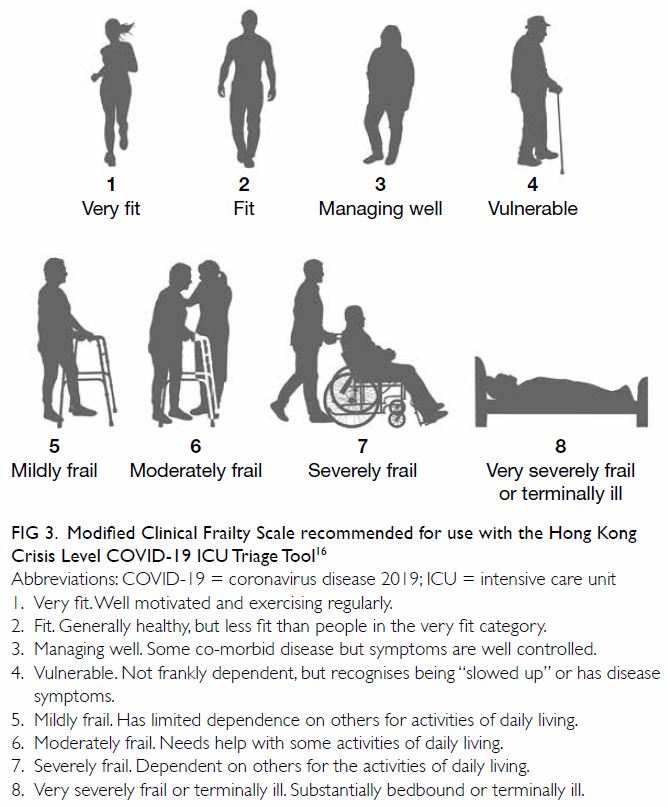

‘quick and clear’ decision making. The clinical frailty

scale (CFS) [Fig 3],16 a modified American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score17 to assess co-morbidity

(Table 3), and last, the clinical assessment of

the number of current organ system failures (OSF), that

has previously been well established as an indicator

to assist the prediction of mortality.

Table 3. Modified American Society of Anesthesiologists score for use with the Hong Kong Crisis Level COVID-19 Intensive Care Unit Triage Tool17

Figure 3. Modified Clinical Frailty Scale recommended for use with the Hong Kong Crisis Level COVID-19 ICU Triage Tool16

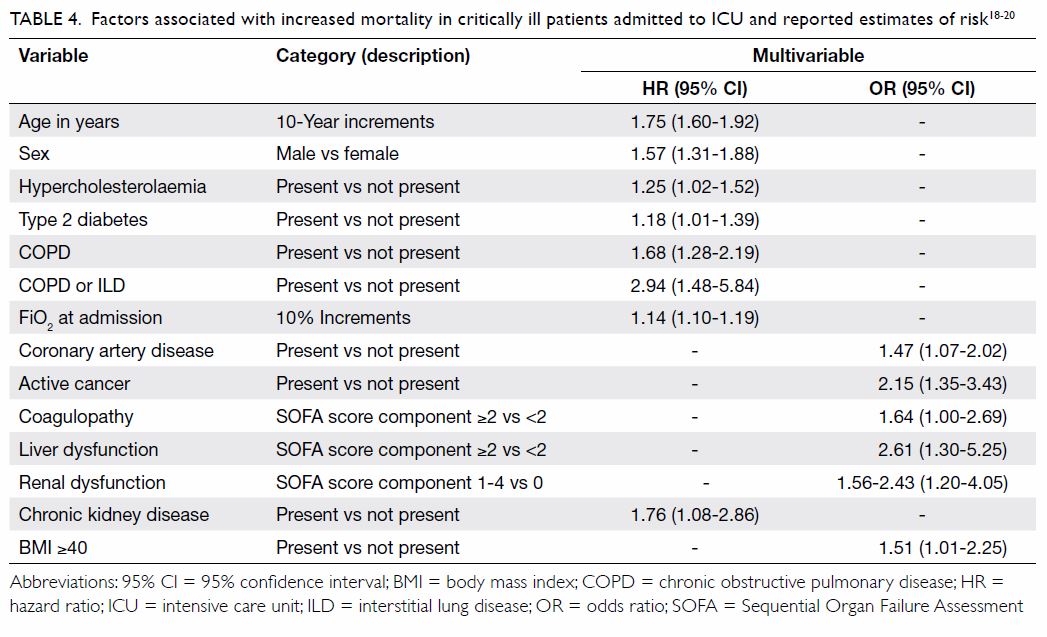

Outcome prognostication by the senior

supervising ICU doctor is largely dependent on

knowledge of the factors associated with poor

outcomes and clinical experience. Although key

relevant factors are captured by the tool, because

COVID-19 is a new condition, we provide a table

summarising mortality risk factors in patients with

COVID-19 who are admitted to ICU to further aid prognostication (Table 4).18 19 20 The data were adapted from countries with ICU practices that are

considered generally similar to those in Hong Kong.

Table 4. Factors associated with increased mortality in critically ill patients admitted to ICU and reported estimates of risk18 19 20

Finally, it has been previously recommended

that time-limited trials may be adopted at the time

of admission.21 A time-limited trial establishes an

agreement between the healthcare team and the

patient/surrogate to apply necessary intensive care

treatment for a pre-determined period of time.

The ICU team keeps the family informed of patient

progress, and when the pre-agreed time limit is

reached, life support therapies are either continued if

the patient has responded positively or withdrawn if

therapy is failing. Setting an appropriate time period

for the trial requires great care,22 and in the setting of

COVID-19, care should be taken to allow sufficient

time for the patient to respond to therapy. The median

number of days of mechanical ventilation and the

length of stay have been reported for patients with

COVID-19 (10 days, and 9 to 12 days, respectively), whose ICU stays are longer than those of patients with other viral pneumonias.18 19

The existing triage framework has been

circulated for comment and feedback from relevant

clinical specialty leadership groups in the Hospital

Authority. Further, the current accompanying tool

has been reviewed by the ad-hoc Hospital Authority

Clinical Ethics Committee Core Group and finalised

after incorporating relevant suggestions for change.

After implementation, the triage working group will

review the need for adjustment and updating of the

guidelines according to local circumstances.

Discussion

The conceptual algorithm recommended herein

broadly follows the existing recommended

framework for individual triage decisions in that

the inclusion criteria are based on a low likelihood

of survival without ICU care (5%-10% or less), if

met. Priorities for admission can then be allocated on the basis of agreed-upon criterion thresholds for

survival, as established in the accompanying triage

tool and adjusted for Hong Kong’s circumstances at a

specific time. Thus, an incremental benefit of at least

40% to 45% would be required to meet the criteria

for priority level 3, but one of at least 70% to 75%

would be required to meet the criteria for priority

level 1. Admission would depend on available

resources after safe maximisation of surge capacity

and the number of patients queuing for admission

(eg, stricter incremental benefit thresholds may

be required during the peak of the pandemic, and

less strict thresholds may be implemented at the

beginning and towards the end). The use of predicted

incremental benefit for decision making has been

previously endorsed by expert consensus groups

when triage is required, both under outbreak and

non-outbreak conditions.1 2 14

The CFS, which has nine variables, was chosen

as the appropriate general health performance

metric, as it meets local practice requirements:

familiarity, ease of use, and having been validated

as a predictor of short- and medium-term ICU

outcomes.23 24 25 26 The well-established ASA score was

chosen for modification to guide assessment of co-morbidities,

as its descriptions are clear, concise,

and logically presented (ASA 2019).17 Further, the

relationship between increasing OSF scores and

higher mortality is well established.27 28 A simple

bedside clinical assessment of organ failure to decide

the number of OSF is recommended, rather than

attempting to determine the SOFA (Sequential Organ

Failure Assessment) score, which requires additional calculations from clinical variables, assessment of

missing variables, and then further prioritisation.29 30

We suggest using a clinical judgement for assessing

end-stage organ failure of the noted organs (eg,

brain, heart, lungs). However, individual units may

choose to use the SOFA score if its calculation is

considered achievable under local circumstances.

After deliberating at length, the group

concluded that the indicative mortalities of the three

chosen variables for determining the priority scores

(general well-being [CFS], co-morbidities [ASA],

and number of OSF) are such that in combination

they are likely to correspond to the subjective

predicted outcomes and survival percentages noted

at the bottom of the notation for each priority score.

The noted predicted survival percentages were

calibrated with the recommendations of previous

consensus expert groups, one who decided to define

‘a minimal acceptable incremental ICU benefit’ in a

resource-limited setting as a 15% to 25% difference

in mortality,10 and the second who adjusted this

difference to be substantially larger (50%) to

account for the increased pressure anticipated in

an outbreak setting.14 The use of the tool to guide

the clinical estimation of likely benefits (outcome of

ICU admission compared with outcome expected if

the patient remained on the ward/other care area)

is necessary for prioritisation of patients who will

benefit most from ICU treatment. Nevertheless,

because individual patients may have overriding

characteristics not captured by the individual or

combined scores, the final decision regarding likely

incremental benefit and subsequent prioritisation should be made by the senior supervising triage doctor.

If there is more than one patient judged to

be within the same priority group, and there is

anticipated queuing for the remaining available

beds, further prioritisation by incremental ICU

benefit, such as saving the most life-years (evaluating

mortality from both acute and chronic disorders)

should be considered. If a tie for ICU admission

candidates remains after these progressive steps, we

recommend that admission be determined by the

first-come, first-served principle.

Because of the complexity of the decision-making

process and the multiple factors that require

careful consideration, final decisions are best made

by an experienced ICU doctor. However, should

uncontrollable circumstances dictate that decisions

need be made by a more junior colleague, the tool

can still provide assistance to guide and enhance

consistent and justifiable decision making. To

prepare for this possibility, preparatory education

should be provided to more junior colleagues

regarding triage decision making to facilitate

appropriate interpretation of this tool.

This tool specifically addresses the triage of

patients for ICU admission. However, when available

ICU resources are overwhelmed, enhanced levels

of care within the ward or available high care areas

should be used for the treatment of cases denied ICU

admission. This could optimise patient outcomes

within the constraints of available alternatives. In this

regard, both invasive and non-invasive mechanical

ventilation is routine practice in the wards and high-care

areas of many hospitals in Hong Kong. This

fact can potentially be harnessed for the treatment

of COVID-19 cases. Patients denied ICU admission

on the basis of triage should be preferentially

considered for diversion to such resources. Hospital-level

coordination and close liaison between hospital

facilities management and those who manage ICU

resources is required to facilitate the appropriate use

of all potentially available resources.31 Although this

tool is designed specifically to guide ICU admission

triage decisions, other users may consider using

the priority assigned by the ICU triage officer to a

refused case to allocate the patient to an appropriate

next level of care.

Many bedside operational factors are part of

the triage process but are not specifically embedded

in this crisis tool. Nevertheless, they are substantially

addressed in the current Admission, Discharge, and

Triage Guidelines, of which the COVID-19 Crisis

Triage Tool is an extension. These include the need

for clear, empathic communication with patients

and surrogates and the implementation of the

appropriate best care plan, including palliation of

symptoms when appropriate, to patients refused ICU

admission. Clear and transparent communication with referring medical teams, mechanisms for

audit and oversight, and channels for feedback and

reassessment are also required.

Important limitations must be acknowledged.

The current guideline is based on the consensus of

experienced Hong Kong clinicians with a history

of performing bedside triage and not high-level,

published medical evidence. Although the prognostic

systems chosen have been well demonstrated

to align with survival prognosis and functional

outcomes, prognostic uncertainty in intensive care

cannot be overcome by a single scoring system. All

prognostic scoring systems, including the CFS,32 have

limitations, and for this reason, the simultaneous use

of multiple scoring methods, as used in this tool, has

been recommended.15

Conclusion

The referral of a patient for ICU care triggers a

complex triage (prioritisation) decision that must

be made when ICU beds are limited. It is expected

that this triage tool, in the form of a detailed decision

aid algorithm, should increase objectivity and

transparency in triage decision making and help to

enhance consistency between doctors both within

and across ICUs in Hong Kong. However, this tool

is an aid rather than a complete substitute for the

carefully considered judgement of an experienced

intensive care clinician.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: GM Joynt.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: GM Joynt.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Christian MD, Sprung CL, King MA, et al. Triage: care

of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and

disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest 2014;146(4

Suppl):e61S-74S. Crossref

2. Joynt GM, Gopalan DP, Argent AA, et al. The Critical

Care Society of Southern Africa Consensus Statement

on ICU Triage and Rationing (ConICTri). S Afr Med J

2019;109:613-29. Crossref

3. Ling L, Ho CM, Ng PY, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients admitted to adult intensive care units in Hong

Kong: a population retrospective cohort study from 2008

to 2018. J Intensive Care 2021;9:2. Crossref

4. Phua J, Faruq MO, Kulkarni AP, et al. Critical care bed

capacity in Asian countries and regions. Crit Care Med

2020;48:654-62. Crossref

5. Murthy S, Wunsch H. Clinical review: international comparisons in critical care—lessons learned. Crit Care

2012;16:218. Crossref

6. Joynt GM, Gomersall CD, Tan P, Lee A, Cheng CA, Wong EL.

Prospective evaluation of patients refused admission to an

intensive care unit: triage, futility and outcome. Intensive

Care Med 2001;27:1459-65. Crossref

7. Shum HP, Chan KC, Lau CW, Leung AK, Chan KW,

Yan WW. Triage decisions and outcomes for patients with

Triage Priority 3 on the Society of Critical Care Medicine

scale. Crit Care Resusc 2010;12:42-9.

8. Nates JL, Nunnally M, Kleinpell R, et al. ICU Admission,

Discharge, and Triage Guidelines: a framework to enhance

clinical operations, development of institutional policies,

and further research. Crit Care Med 2016;44:1553-602. Crossref

9. Blanch L, Abillama FF, Amin P, et al. Triage decisions for

ICU admission: report from the task force of the World

Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care

Medicine. J Crit Care 2016;36:301-5. Crossref

10. Joynt GM, Gopalan DP, Argent AA, et al. The Critical

Care Society of Southern Africa Consensus Guideline

on ICU Triage and Rationing (ConICTri). S Afr Med J

2019;109:630-62. Crossref

11. Legislative Council, HKSAR Government. Report of the

Select Committee to inquiry into the handling of the severe

acute respiratory syndrome outbreak by the Government

and the Hospital Authority. 2004. Available from: https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr03-04/english/sc/sc_sars/reports/sars_rpt.htm. Accessed 15 Sep 2020.

12. Gomersall CD, Tai DY, Loo S, et al. Expanding ICU facilities

in an epidemic: recommendations based on experience

from the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong and Singapore.

Intensive Care Med 2006;32:1004-13. Crossref

13. Guidet B, Hejblum G, Joynt G. Triage: what can we do to

improve our practice? Intensive Care Med 2013;39:2044-6. Crossref

14. Sprung CL, Joynt GM, Christian MD, Truog RD, Rello J, Nates JL. Adult ICU triage during the coronavirus

disease 2019 pandemic: who will live and who will die?

Recommendations to improve survival. Crit Care Med 2020;48:1196-202. Crossref

15. Flaatten H, Beil M, Guidet B. Prognostication in older ICU patients: mission impossible? Br J Anaesth 2020;125:655-7. Crossref

16. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ

2005;173:489-95. Crossref

17. American Society of Anaesthesiologists. ASA Physical

Status Classification System. 2019. Available from: https://

www.asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines/asa-physical-status-classification-system. Accessed 16 Sep 2020.

18. Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, et al. Factors associated with death in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019

in the US. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:1-12.Crossref

19. Grasselli G, Greco M, Zanella A, et al. Risk factors

associated with mortality among patients with COVID-19

in intensive care units in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA Intern

Med 2020;180:1345-55. Crossref

20. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with

COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study.

Lancet 2020;395:1763-70. Crossref

21. Quill TE, Holloway R. Time-limited trials near the end of life. JAMA 2011;306:1483-4. Crossref

22. Vink EE, Azoulay E, Caplan A, Kompanje EJ, Bakker J.

Time-limited trial of intensive care treatment: an overview

of current literature. Intensive Care Med 2018;44:1369-77. Crossref

23. Bagshaw M, Majumdar SR, Rolfson DB, Ibrahim Q,

McDermid RC, Stelfox HT. A prospective multicenter

cohort study of frailty in younger critically ill patients. Crit

Care 2016;20:175. Crossref

24. Bagshaw SM, Stelfox HT, McDermid RC, et al. Association

between frailty and short- and long-term outcomes among

critically ill patients: a multicentre prospective cohort

study. CMAJ 2014;186:E95-102. Crossref

25. Brummel NE, Bell SP, Girard TD, et al. Frailty and subsequent disability and mortality among patients with

critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196:64-72. Crossref

26. Flaatten H, De Lange DW, Morandi A, et al. The impact of

frailty on ICU and 30-day mortality and the level of care

in very elderly patients (≥80 years). Intensive Care Med

2017;43:1820-8. Crossref

27. Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE.

Prognosis in acute organ-system failure. Ann Surg

1985;202:685-93. Crossref

28. Peres Bota D, Melot C, Lopes Ferreira F, Nguyen Ba V,

Vincent JL. The Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score

(MODS) versus the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

(SOFA) score in outcome prediction. Intensive Care Med

2002;28:1619-24. Crossref

29. Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related

Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ

dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group

on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of

Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 1996;22:707-10. Crossref

30. Ferreira FL, Bota DP, Bross A, Mélot C, Vincent JL. Serial

evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in

critically ill patients. JAMA 2001;286:1754-8. Crossref

31. Joynt GM, Loo S, Taylor BL, et al. Chapter 3. Coordination

and collaboration with interface units. Recommendations

and standard operating procedures for intensive care unit

and hospital preparations for an influenza epidemic or

mass disaster. Intensive Care Med 2010;36(Suppl 1):S21-31. Crossref

32. Darvall JN, Bellomo R, Bailey M, et al. Frailty and outcomes

from pneumonia in critical illness: a population-based

cohort study. Br J Anaesth 2020;125:730-8. Crossref