© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Tsan Yuk Hospital and the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong

TW Wong, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)

Member of the Education and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

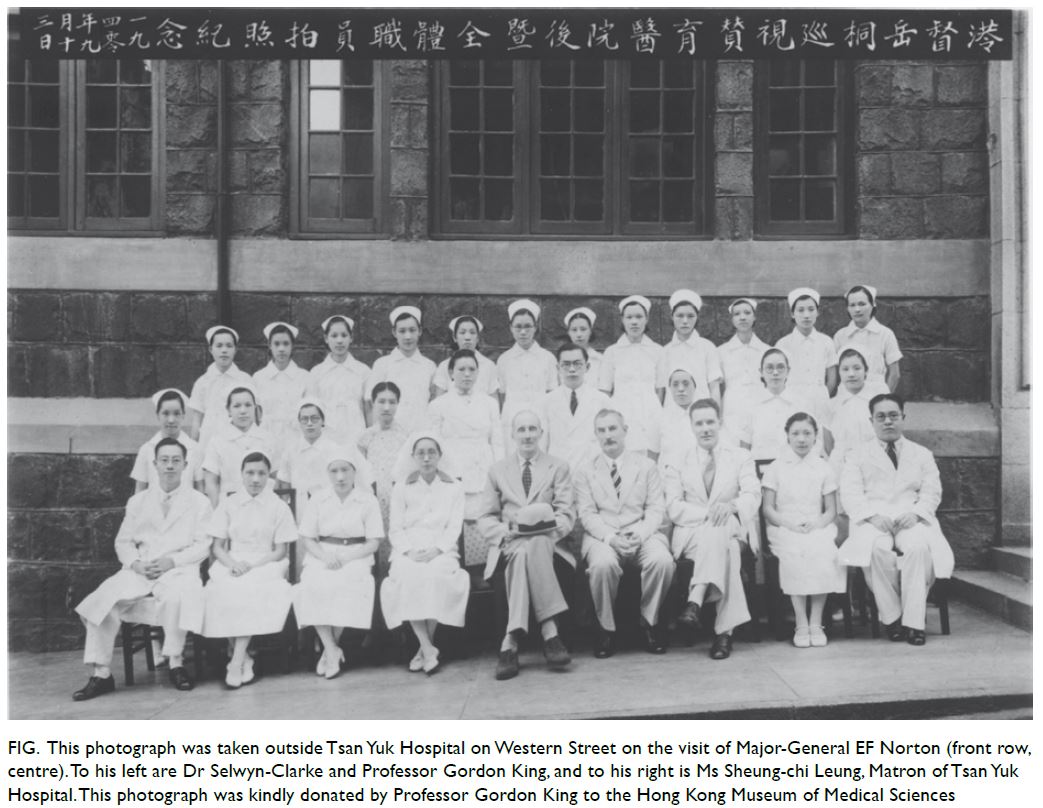

Major-General EF Norton arrived in Hong Kong

August 1940 as acting Governor while Sir Geoffry

Northcote was on sick leave (Fig). A year later, Sir

Mark Young became Governor in September 1941

just a few months before Japanese aggression. In

this familiarisation visit to the Hospital Norton was

accompanied by Dr Percy Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke

and Professor Gordon King. All the people in the

picture, except Norton, and the hospital would soon

be embroiled in the darkest years of the Japanese

Occupation from December 1941 to August 1945.

Dr Selwyn-Clarke came to Hong Kong in

March 1938 to join the Medical Department as its

head. He joined the Colonial Medical Service in 1919

and had spent most of his medical career in Africa prior to his transfer to Hong Kong.1 He was facing a

huge challenge, which occurred predated his arrival.

In 1937, the population in Hong Kong was around

1 million, and 100 000 more came to Hong Kong

as refugees due to the invasion of China by Japan.

The local medical facilities were overwhelmed not

to mention the need to feed and house this sudden

influx of people. Tuberculosis was rampant and

nutritional deficiencies disorders like beriberi and

pellagra were also common.

The capture of Canton by the Japanese Army in

October 1938 brought another wave of refugees. The

British government had to prepare for the possible

aggression from Japan and ordered the Hong Kong

government to prepare for its own defence with a target of surviving a siege for 130 days. So, in addition

to maintaining the daily operation of the medical and

health services, Dr Selwyn-Clarke had to transform

the existing hospitals to become casualty clearing

hospitals and relief hospitals and create 19 first aid

posts in some schools. Meanwhile, he was tasked

to prepare enough drugs, medical supplies, etc that

could last that long. The government evacuated

British women and children from Hong Kong in July

1940, 2 months before the picture was taken.

The Japanese military invaded Hong Kong on

8 December 1941 and the Hong Kong government

capitulated on Christmas Day after 18 days of

resistance. Hong Kong people suffered a lot during

the ensuing Japanese occupation, which lasted for

44 months. Dr Selwyn-Clarke did something unusual

hoping to lessen human suffering. He proposed to

the Military government to allow him to stay on so

that he could direct his staff to maintain the public

health services, eg removing dead bodies due to

the war, maintaining the sewage system, etc. The

Japanese authority agreed reluctantly to appoint

him as “adviser” for fear of an outbreak of infectious

disease. Dr Selwyn-Clarke also sought consent

from the Governor as his act could be accused as

collaboration with the enemy. In addition to running

the necessary health services with only a skeleton

staff, he also took it on himself to look after people in

internment camps and their dependents outside who

had no support. An Informal Welfare Committee

was formed and with donations from kind people

he was able to provide additional food and medical

supplies to those interned.2 For example, when

diphtheria broke out in the Sham Shui Po prisoner-of-

war camp, he was able to “smuggle” some anti-toxin

to the camp doctors and saved a few lives.

His resourcefulness and kindness earned him the

name of a “hard-boiled saint” among his supporters.

But his humanitarian work and its network drew

the attention of the Kempeitai and he was arrested

in May 1943 for alleged spying activities. He was

interrogated and tortured for refusing to admit

his crime and name his associates. As a result, he

suffered permanent injuries to his spine and left leg

and had to walk with aid afterwards. He was released

from Stanley Prison on 8 December 1944 to a civilian

internment camp to resume his work as a doctor till

the Japanese surrender in August 1945. Under his

leadership, the medical and health services were

restored soon after British resumed control. Despite

his ordeal under the Japanese Kempeitai, he refused

to act as a witness in the War Crime Tribunal. As

a true humanitarian he was known to use his own

money to buy each Japanese prisoner of war under

his supervision a toothbrush. In 1947, he left Hong

Kong to become the governor of the Seychelles.

The new Nurses’ Quarter of Kwong Wah Hospital

was named after him in 1952 to commemorate his guidance to the Tung Wah Medical Committee

during his time as head of the Medical Department.

Prof Gordon King came to China in 1927 as

a medical missionary. Due to the invasion of China

by Japan, he had to leave Cheeloo University in 1938

to take up headship of Department of Obstetrics

and Gynaecology at The University of Hong Kong

(HKU). At the time the picture was taken in 1940,

Prof King was Dean of the Medical Faculty, and he

was appointed medical superintendent of the Relief

Hospital at the University main buildings when war

broke out. Unlike Dr Selwyn-Clarke, who decided to

stay after the fall of Hong Kong, Prof King escaped

to Free China in February 1942. He became the key

person taking care of HKU students there, including

finding places for them in the Chinese universities

and also getting financial support from the British

Government.3 This was no easy task as he needed

to convince both the Chinese Minister of Education

and the British Foreign Office. Eventually he had to

provide relief for 346 students, which was more than

half of the total student body of HKU. As for the

115 medical students, they were placed in eight

different universities to continue their studies.

Although he was appointed Visiting Professor

of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the National

Shanghai Medical College at Koloshan, his main

preoccupation was looking after the HKU students.

After the surrender of Japan, Prof King returned

to Hong Kong and became the Assistant Director

of Medical Services under the temporary military

government of Rear-Admiral Harcourt. His main

responsibility was the re-organisation of the

government hospitals and clinics. His efforts in

helping the students were repaid amply by the

supply of greatly needed medical staff from these

new graduates from Free China. Of the 63 wartime

students who received a medical degree under

the Emergency Committee after the war included

famous doctors such as Dr Gerald Choa and Prof GB

Ong. Prof King resigned from HKU in 1956 to take

up the deanship of the new medical school of the

University of Western Australia.

Ms Sheung-chi Leung(梁尚志)was Matron

of Tsan Yuk Hospital since its establishment in

1922. Ms Leung received training in nursing

and midwifery at Nethersole Hospital. She spent

6 months at Rotunda Hospital, Ireland in 1926 to

gain more experience in running a maternity unit.4

Before the war, she had already been appointed a

member of the Nurses Board serving from 1938

to 1941. After the surrender on Christmas day, Ms

Leung stayed on to run the hospital with only meagre

supply. Dr Selwyn-Clarke provided extra funds to her

so that indigent patients could be taken care of. The

Japanese Military Government had requisitioned

Queen Mary Hospital, Kowloon Hospital and Tung

Wah Eastern Hospital. Nethersole became the main civil hospital on Hong Kong Island and Kwong Wah

Hospital was the only one still open to the public on

Kowloon side. The number of deliveries dropped to

around 20% of pre-war level though the maternal

mortality rate had almost tripled according to

records of Kwong Wah Hospital.5 Tsan Yuk Hospital

had to merge into Nethersole Hospital in December

1944 due to lack of funds. Ms Leung and her staff had the very difficult task of storing away hospital

assets while still providing service at Nethersole.

After Hong Kong was repossessed by the British

on 30 August 1945, her team reopened Tsan Yuk

Hospital with amazing speed on 6 October 1945. She

served one term (1949-1952) on the Midwives Board

after the war and retired in 1951. She was honoured

with an MBE on her retirement.

References

1. Horder M. The hard boiled saint: Selwyn-Clarke in Hong Kong. BMJ 1995;311:492-5. Crossref

2. Report compiled by direction of His Excellency Mr. FC Gimson, CMG, of duties performed by Dr. P S Selwyn-Clarke, Director of Medical Services, and non-interned staff and volunteer helpers, during the occupation of Hong

Kong by the Japanese forces. CO129/592/#1: p19-23.

3. Matthews C, Cheung O. Dispersal and Renewal: Hong Kong University during the War Years. Hong Kong University

Press; 1998.

4. Cheung SM. The 28-year history of Tsan Yuk Hospital. In: The 10th Anniversary Special Edition. Hong Kong Nurses

and Midwives Association; 1950.

5. Leung WC, Tai SM, Sham A, Yip W, See S. Labour room birth records of Kwong Wah Hospital since 1935. Hong Kong Med J 2021;27:374-6. Crossref

Figure. This photograph was taken outside Tsan Yuk Hospital on Western Street on the visit of Major-General EF Norton (front row, centre). To his left are Dr Selwyn-Clarke and Professor Gordon King, and to his right is Ms Sheung-chi Leung, Matron of Tsan Yuk Hospital. This photograph was kindly donated by Professor Gordon King to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences