Hong Kong Med J 2021 Dec;27(6):405–12 | Epub 17 Dec 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Effectiveness of a childbirth massage programme for labour pain relief in nulliparous pregnant women at term: a randomised controlled trial

CY Lai, MSc (Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism), MSc Nursing (Midwifery)1; Margaret KW Wong, MSc (Women’s Health Studies)2; WH Tong, MSc (Public Health)2; SY Chu, MN (Clinical Leadership); BSc (Health Science)3; KY Lau, MSc (Women’s Health Studies)2; Agnes ML Tam, MSc (Women’s Health Studies)2; LL Hui, PhD (Community Medicine)4; Terence TH Lao, MD, FRCOG1; TY Leung, MB, ChB, MD1

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong

4 Department of Paediatrics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Ms CY Lai (cylai@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The effect of massage for pain relief

during labour has been controversial. This study

investigated the efficacy of a programme combining

intrapartum massage, controlled breathing, and

visualisation for non-pharmacological pain relief

during labour.

Methods: This randomised controlled trial was

conducted in two public hospitals in Hong Kong.

Participants were healthy low-risk nulliparous

Chinese women ≥18 years old whose partners were

available to learn massage technique. Recruitment

was performed at 32 to 36 weeks of gestation;

women were randomised to attend a 2-hour

childbirth massage class at 36 weeks of gestation or

to receive usual care. The primary outcome variable

was the intrapartum use of epidural analgesia or

intramuscular pethidine injection.

Results: In total, 233 and 246 women were

randomised to the massage and control groups,

respectively. The use of epidural analgesia or

pethidine did not differ between the massage and

control groups (12.0% vs 15.9%; P=0.226). Linear-by-linear analysis demonstrated a trend whereby

fewer women used strong pharmacological pain

relief in the massage group, and a greater proportion

of women had analgesic-free labour (29.2% vs 21.5%;

P=0.041). Cervical dilatation at the time of pethidine/epidural analgesia request was significantly greater in the massage group (3.8 ± 1.7 cm vs 2.3 ± 1.0 cm;

P<0.001).

Conclusion: The use of a massage programme appeared to modulate pain perception in labouring

women, such that fewer women requested epidural

analgesia and a shift was observed towards the use

of weaker pain relief modalities; in particular, more

women in the massage group were analgesic-free

during labour.

New knowledge added by this study

- In this randomised controlled trial of healthy low-risk nulliparous Chinese women, fewer women used strong pharmacological pain relief in the childbirth massage group, and a greater proportion of women had analgesicfree labour, compared with the control group.

- Cervical dilatation at the time of pethidine/epidural analgesia request was significantly greater in the childbirth massage group than in the control group.

- A structured childbirth massage programme delivered by qualified midwife trainers can provide couples with both theoretical knowledge and practical skills, which help to modulate pain perception among labouring women.

- With appropriate training, massage can be an efficacious option for labour pain relief with no associated adverse effects on delivery.

Introduction

Labour is regarded as a time of suffering in a

woman’s life, during which she may experience intensive pain that lasts for many hours. Ineffective

labour pain management could create a negative

life experience for a woman, which may negatively impact postpartum sexual and marital satisfaction.1 2

Labour pain involves both physical and psychological

elements such as uterine contractions, tension, fear,

anxiety, and the sensations of powerlessness and a

loss of control.3 Current remedies for labour pain

include pharmacological and non-pharmacological

interventions. The most common pharmacological

interventions include nitrous oxide inhalation,

the injection of narcotic analgesics (eg, pethidine),

and epidural analgesia. However, these methods

are associated with adverse effects such as nausea

and vomiting, longer first and second stages of

labour, hypotension, motor blockade, fever, and

urinary retention; they can also lead to neonatal

respiratory depression and newborn sleepiness

that affects breastfeeding.4 5 6 7 8 9 Hence, women prefer

safer and simpler non-pharmacological pain relief

methods.10 11

A notable non-pharmacological remedy is

massage, which may provide pain relief to the site

of application, along with overall psychological

relaxation.12 The pressure applied during massage

is presumed to block the transmission of pain

impulses to the brain, while stimulating local

release of endorphins.13 Randomised controlled

trials concerning intrapartum massage have been

conducted in various countries over the past two

decades.12 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 However, there have been conflicting

findings concerning beneficial effects (ie, reductions

in pain score or the use of pharmacological

analgesia)12 14 15 16 17 21 because of small sample sizes which ranged from 28 women12 to 176 women.21

Furthermore, the duration of intrapartum massage

was either unspecified15 21 or lasted for only 30 to

40 minutes.12 14 18 19 22 23 In addition, intrapartum

massage was performed by various types of people:

student midwives,22 therapists17 19 or partners who

had received training by therapists immediately

before labour.12 14 These factors probably influenced

the effectiveness, consistency, and duration of the

application of massage. A recent Cochrane review

concluded that the current quality of evidence

regarding intrapartum massage is low to very

low.24 Therefore, this randomised controlled study

investigated the efficacy of a comprehensive massage

programme, combined with controlled breathing

and visualisation—all initiated during the antenatal

period—as a non-pharmacological pain relief

method during labour, with the goal of reducing

pethidine or epidural analgesia use.

Methods

Design and recruitment

This randomised controlled study was conducted

in two public hospitals in Hong Kong, where

the midwives were responsible for intrapartum

management and natural vaginal delivery of low-risk

pregnancies. The respective annual childbirth rates

were approximately 5000 and 7000; the caesarean

section rates were 21% and 23%.25 Recruitment

commenced in September 2016 and completed in

December 2017. The recruitment of women was

conducted at 32 to 36 weeks of gestation during

their routine antenatal visit by a team of research

midwives. The inclusion criteria were low-risk

nulliparous Chinese women aged ≥18 years,

who could communicate in Cantonese, and who

carried a singleton pregnancy without known

contraindications for vaginal delivery. Exclusion

criteria were the use of massage among women in

the control group, the absence of a partner to learn

the massage technique, planned delivery in hospitals

other than the study sites, and planned caesarean

delivery. There was no exclusion of recruited

women who attempted vaginal delivery or induction

of labour but eventually required intrapartum

caesarean delivery.

Randomisation was conducted via two-by-two

blocking with a block size of 4; a computer-generated

number indicating either the study or

control group was sealed in an opaque envelope.

After a woman had provided written informed

consent to participate, the midwife revealed the

group allocation by opening the envelope. Because

there were multiple midwifery staff responsible for

participant recruitment at different occasions, none

of the staff were aware of the allocation of previous

participants; hence, they were unable to guess the

group allocation.

Intervention

Couples (ie, participating women and their partners)

randomised to the massage group were invited to

attend a 2-hour childbirth massage programme

class at 36 weeks of gestation. This programme

was based on the United Kingdom’s Royal College

of Midwives accredited course ‘Towards Natural

Childbirth and Beyond’.26 It included a 30-minute

theoretical explanation of the evidence

underpinning the childbirth massage programme,

followed by a 90-minute practicum. During the

90-minute practicum, the couples received training

by accredited midwifery trainers with respect to

the massage technique, controlled breathing, and

visualisation, in accordance with the methods used

in previous studies.16 20 The massage areas included

the lower back and four limbs. Couples were taught

how to synchronise the massage strokes with slow

rhythmic breathing. Visualisation (ie, a mind

mapping component) was also taught.26 In this

process, the woman was asked to imagine something

comfortable, which could bring her to a relaxed

state. Subsequently, the couples were encouraged to

practise the massage technique regularly at home in

the evening, in a dimly lit and quiet environment,

with the aim of encouraging relaxation and

improving the quality and duration of sleep.27 The

control group received standard antenatal education

without instruction concerning massage, controlled

breathing, or visualisation techniques.

When a woman in the massage group was

admitted to the study hospital at onset of labour

or for planned labour induction, her partner was

first asked to demonstrate massage technique to the

research team midwives to ensure that the partner

could perform the procedure properly. If labour was

not yet established, each woman was encouraged

to relax through self-massage on her abdomen and

legs. When labour commenced, the partner stayed

to provide arm and shoulder massage for relaxation

or lateral sacral massage for pain relief, according

to the woman’s preference. There was no time limit

for massage as long as the couple was happy and felt

comfortable to continue the procedure throughout

the labour. The partner could take a break in times

of fatigue, or when the woman fell asleep. The

partners of women in the control group were also

encouraged to accompany the women during labour

and delivery. Women in both groups otherwise

received the same intrapartum care. They received

explanations concerning the effectiveness of various

analgesic methods according to the ranking of

reported efficacy4 7: epidural was ranked highest,

followed by pethidine, then nitrous oxide and other

non-pharmacological analgesia methods (including

transcutaneous nerve stimulation, birthing ball, and

warm pads). Women could choose various methods

or a combination of methods according to their pain tolerance and acceptance, using a step-up approach

or direct implementation of the most effective

methods. The degree of labour pain was assessed

using the visual analogue scale for pain (ranging

from 0 [no pain] to 10 [most painful]) at different

stages of labour: latent phase (cervical dilatation of

1-3 cm), active phase (cervical dilatation of 4-7 cm),

late active phase (cervical dilatation of 8-9 cm), and

second stage (cervical dilatation of 10 cm); it was also

assessed when the women first requested pethidine

or epidural analgesia.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of this study was the use of

the two most effective pharmacological methods (as

described above): intramuscular pethidine injection

or epidural analgesia. Women were also categorised

according to the type of analgesia that they

eventually received: none of the analgesic methods;

non-pharmacological methods only; nitrous oxide ±

non-pharmacological methods; pethidine ± other

pain relief except epidural; or epidural ± above

methods. The proportions of women that received

each type of analgesia were also compared as one of

the secondary outcomes. Other secondary outcomes

included intrapartum caesarean rate, duration of

labour, the pain score at the point when the women

first requested pethidine or epidural analgesia, the

interval between the onset of labour to the time of

making such a request, and the cervical dilatation at

which such a request was made.

Sample size calculation

A previous study reported a reduction of 60% in the

epidural rate with the use of intrapartum massage

when compared with the control group.2 Therefore,

our study sample size was calculated based on the

assumption that the requirement for pethidine

injection or epidural analgesia could be reduced by

60% (ie, from the current 15% according to Hospital

Authority data to 6%) in the study group. Using an

80% power (beta) threshold and a two-tailed alpha

value of 5%, we calculated that 181 participants were

required in each arm. The method of calculation

was obtained from the website of Department of

Obstetrics and Gynaecology, the Chinese University

of Hong Kong (http://www.obg.cuhk.edu.hk/ResearchSupport/StatTools/index.php). Because we

anticipated that 40% of the recruited participants

would be excluded (eg, because of a shift to a private

hospital for delivery, change to elective caesarean

section, or withdrawal from the study), we planned

to recruit 300 participants for each arm.

Statistical analysis

The Chi squared test and t test were used to assess

differences in baseline characteristics, obstetric outcomes, neonatal outcomes, and the proportions

of women using specific pharmacological pain relief

methods between the massage and control groups.

Linear-by-linear association was used to assess trends

regarding the use of different types of analgesia. The

t test was used to compare between-group differences

in the stage of labour, cervical dilatation, and pain

score among participants who used pethidine/epidural, as well as the mean pain scores in different

phases of labour among participants who did not

use any pain relief modalities. A P value of <0.05 was

considered statistically significant. All analyses used

a per-protocol approach. Intention-to-treat analysis

(including all participants recruited at baseline)

could not be conducted because information

collected during labour (eg, the use of pain relief

modalities) was not available for participants who

delivered in other hospitals, required caesarean

section before pain labour commenced, or withdrew

from the study. Statistical analyses were performed

using SPSS software (Windows version 22.0; IBM

Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

Results

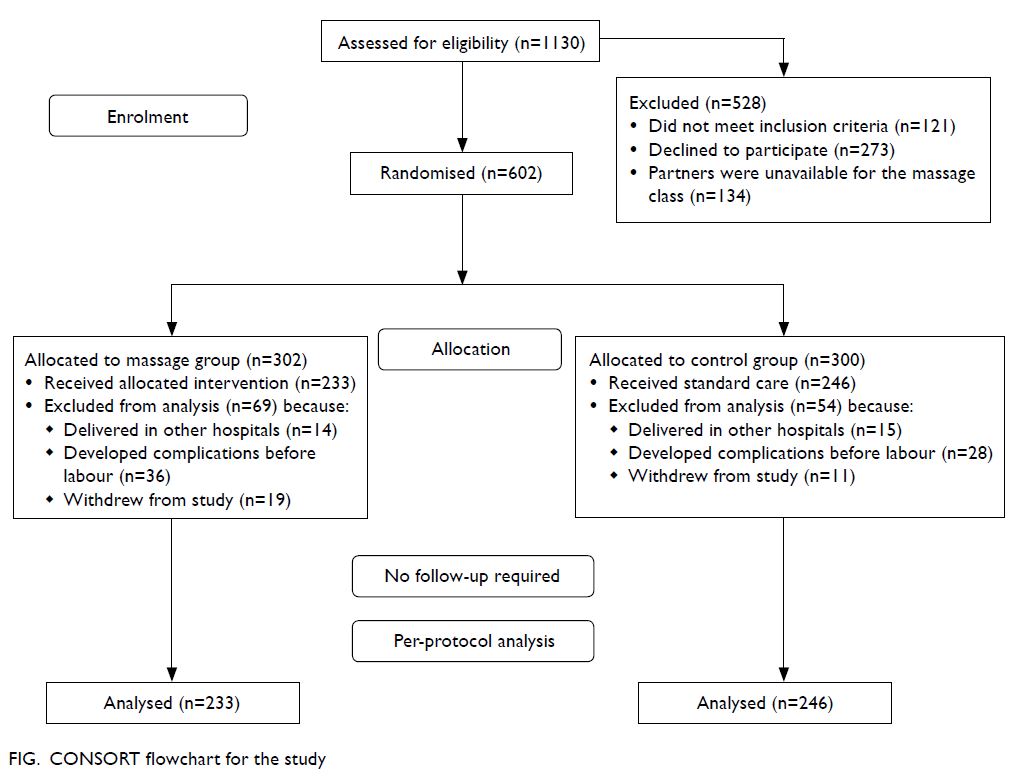

Of the 1130 women eligible for this study, 528 were

excluded for reasons shown in the Figure; thus, 602 women were randomised to the massage group

(n=302) and control group (n=300). Furthermore,

69 (22.8%) and 54 (18.0%) women were subsequently

excluded from the massage and control groups,

respectively, for reasons such as delivery in private

hospitals, planned caesarean section, development

of complications before labour, or withdrawal from

the study. Finally, 479 pregnant women (233 in the

massage group and 246 in the control group) were

included in the per-protocol analysis.

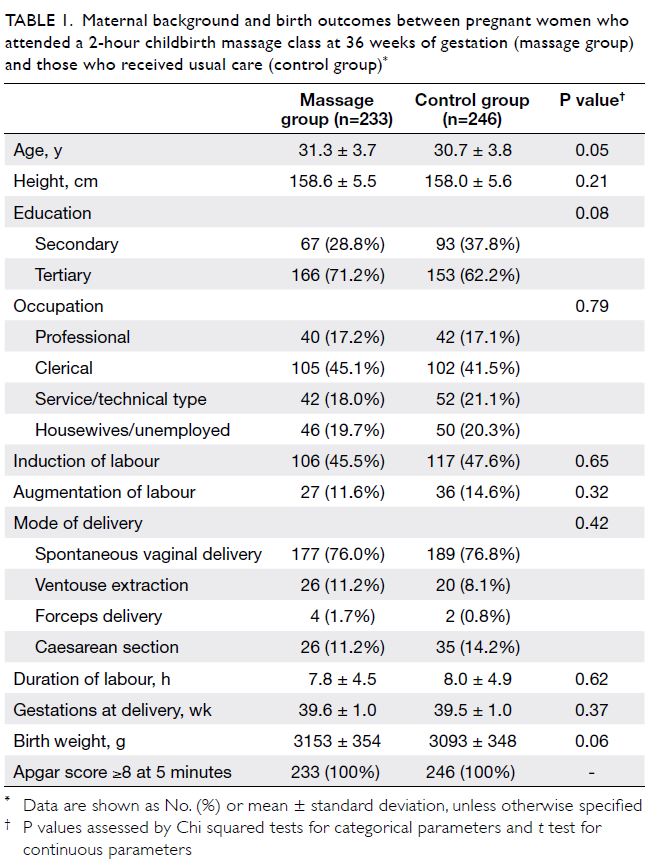

There were no significant differences between

groups in terms of maternal age, height, or

demographic characteristics nor in the proportions

of women who underwent induction of labour,

augmentation of labour, or delivered by caesarean

section (Table 1). The mean duration of labour did

not differ between the massage and control groups.

No significant differences were found in gestational

age at delivery, birthweight, or the proportion of

babies with Apgar score ≥8 at 5 minutes (Table 1).

All women in the massage group practised massage

during labour (n=233). The duration of massage

ranged from 35 minutes to 195 minutes (median,

100 minutes).

Table 1. Maternal background and birth outcomes between pregnant women who attended a 2-hour childbirth massage class at 36 weeks of gestation (massage group) and those who received usual care (control group)

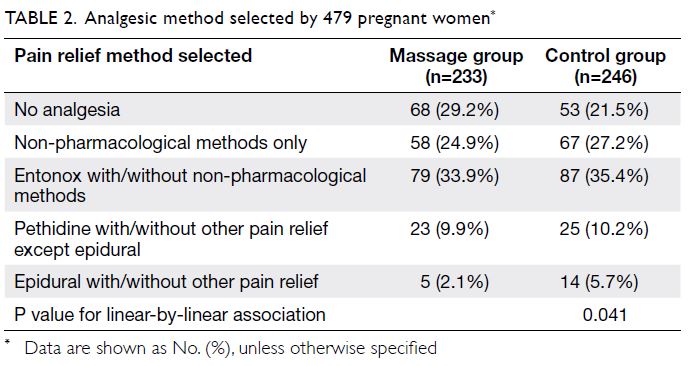

The proportion of women who used pethidine

or epidural did not significantly differ between

the massage and control groups (12.0% vs 15.9%; P=0.226). However, linear-by-linear association

analysis showed a significant shift in the massage

group, from using stronger analgesics (eg, epidural

analgesia: 2.1% in the massage group vs 5.7% in the

control group) to weaker analgesics. Thus, more

women in the massage group required none of the

analgesics, compared with women in the control

group (29.2% vs 21.5%; P=0.041) [Table 2].

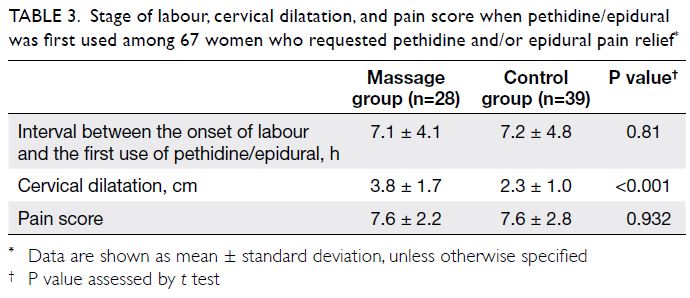

Among women who needed pethidine or

epidural for pain control, there was no difference

between the two groups in terms of the pain score

at the point when they requested these pain relief

modalities, or the interval between the onset of labour

to the time of requesting these modalities (Table 3).

However, the cervical dilatation at which pethidine

or epidural was first requested was significantly

greater in the massage group (3.8 ± 1.7 cm)

than in the control group (2.3 ± 1.0 cm; P<0.001)

[Table 3].

Table 3. Stage of labour, cervical dilatation, and pain score when pethidine/epidural was first used among 67 women who requested pethidine and/or epidural pain relief

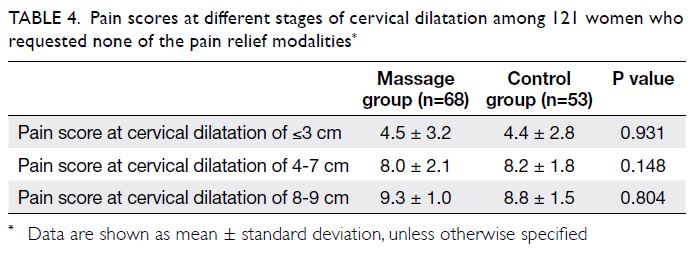

Among women who needed none of the pain

relief modalities, the pain scores progressively

increased with cervical dilatation, although there

were no differences between the two groups

(Table 4).

Table 4. Pain scores at different stages of cervical dilatation among 121 women who requested none of the pain relief modalities

Discussion

Although our study did not show a statistically

significant reduction in the number of women who

used either pethidine or epidural analgesia with the

practice of massage (12.0% vs 15.9%), linear-by-linear

analysis revealed that there was a statistically

significant overall shift in the pattern of analgesics

use in the massage group: a smaller proportion of

women requested epidural analgesia (2.1% vs 5.7%)

and a larger proportion of women requested none of

the pain relief methods (29.2% vs 21.5%). Our results

suggest that the pain perceptions of labouring

women were improved by the training and practice

of massage, controlled breathing, and visualisation.

Thus, some women who initially requested the

stronger methods (eg, epidural analgesia) might

have achieved satisfactory pain control with weaker

analgesic methods (eg, pethidine or nitrous oxide).

Similarly, women who initially requested pethidine

or nitrous oxide might have shifted to non-pharmacological

methods only; this led to a greater

proportion of women in the massage group who

requested no analgesia.

Interpretation

Although pain scores are commonly used to compare

analgesic effectiveness, such comparisons are often

difficult on the basis of a single pain score during

labour. This is because the labour process is generally

long and its characteristics are variable; labouring

women might use more than one method of pain

relief at different stages of labour. Nonetheless, if the pain is intolerable, labouring women require

a stronger analgesic method.28 Hence, we used a

pattern of analgesic utility (rather than a single

pain score) as an indicator for the effectiveness

of the massage programme; our linear-by-linear

association findings indicated that the massage

programme may reduce pain perception among labouring women. Furthermore, the mean cervical

dilatation at the time of pethidine or epidural

analgesia request was higher in the massage group

than in the control group (3.8 ± 1.7 cm vs 2.3 ± 1.0 cm).

Notably, among women who requested pethidine

or epidural analgesia, the pain score at the point of

first pethidine or epidural analgesia request was very

similar between the massage and control groups

(7.6 ± 2.2 vs 7.6 ± 2.8). Although the midwives were

not blinded to the allocation in this study, women in

both groups received the same intrapartum care and

could choose pain relief methods according to their

pain tolerance and acceptance. These results further

support the notion that the practice of massage

might have modulated the pain perception among

labouring women, such that they only requested

stronger pharmacological pain relief during later

phases of labour; additional studies are required to

confirm the underlying biological mechanism.

Janssen et al17 also reported a delay in epidural

insertion by 1 cm of cervical dilatation (5.9 cm in the

massage group vs 4.9 cm in the control group) in their

randomised controlled trial. However, they failed to

show a significant reduction in the rate of epidural

analgesia use (81.1% in the massage group vs 65.0%

in the control group). Importantly, their participants

only learned and practised massage at the time of

labour, while our participants began learning the

massage programme during the antenatal period.

In another randomised controlled trial,

Levett et al21 showed that the incidence of epidural

analgesia was significantly reduced (from 68.2% to 23.9%) in a cohort of 176 Australian patients.

However, their control group had a baseline epidural

analgesia rate of 68.2%, which was much higher than

the rate in our control group (ie, 5.7%, which is similar

to the 6.6% reported previously in Hong Kong29)

Possible reasons for the large difference in epidural

rates between Australia and Hong Kong include

variations in midwifery practices, pain tolerance

among labouring women, and limited resources in

Hong Kong public hospitals. Other obstetric practice

differences include an overall (massage and control

groups combined) higher normal vaginal delivery

rate in our cohort than in the cohort reported by

Levett et al21 (76.4% vs 57.9%); our overall cohort

also exhibited a lower instrumental delivery rate

(10.9% vs 17.0%) and a lower caesarean section rate

(12.7% vs 25.1%). Regardless of our low baseline

epidural rate, we found a 60% reduction in epidural

use in the massage group (2.1%), compared with

the control group (5.7%). Finally, Levett et al21 only

reported the incidence of simultaneous use of

pethidine and nitrous oxide, whereas we stratified

analgesic methods according to the strength of

pain relief; this allowed us to detect an overall shift

towards weaker analgesics among women in the

massage group.

Importantly, neither study (this study or the

study by Levett et al21) demonstrated any reduction

in the overall duration of labour in nulliparous

women, although the cohort reported by Levett et al21

exhibited a marked reduction in the rate of epidural

use. In contrast, Bolbol-Haghighi et al22 showed that

massage practice was associated with significantly

shorter durations in both the first stage (9.0 hours

vs 11.5 hours) and the second stage of labour

(49 minutes vs 64 minutes) among a cohort of Iranian

women. However, their study included multiparous

women with an overall vaginal delivery rate over

95%; they did not describe the availability of epidural

analgesia for their participants. In summary, it

remains unclear whether the practice of massage

has consistent effects on labour progression; the

underlying mechanisms of such effects are unknown.

Strengths and limitations

This study had several strengths. First, it involved

a large number of nulliparous labouring women.

To our knowledge, this is the largest number of

such women among similar published studies; it

allowed us to identify any changes in the utilisation

of different levels of analgesic methods, without

any confounding effects related to multiparity.20 22

Second, this study involved a team of accredited

and dedicated midwife trainers, which enabled us

to ensure that a consistent high-quality massage

technique was applied to women in the study. Third,

training at 36 weeks of gestation allowed each

couple (ie, a participating woman and her partner) to have sufficient time to practise massage at home

and refine their technique before the woman began

labour. Fourth, on admission prior to delivery,

an accredited midwife trainer was available to

verify each couple’s massage technique and ensure

quality. Finally, there was no limit to the duration

of intrapartum massage; women could receive their

preferred amount of massage to achieve optimal

results.

There were some notable limitations in this

study. First, because of the pain relief methods

used, we were unable to incorporate blinding in

the trial design. However, the midwives providing

intrapartum care were not involved in data

collection. Second, approximately one-fifth of the

participants in each group had changes to their

childbirth plan, including shift to a private hospital

or to planned caesarean delivery; thus, they were

excluded from the final analysis. Third, we could

only assess the intrapartum massage provided by the

participating women’s partners; we could not assess

the breathing and visualisation practice at home,

which are also essential components of the overall

massage programme. Finally, because continuous

foetal heart monitoring was the standard method of

intrapartum foetal surveillance in Hong Kong during

the study period, women were unable to move freely

during labour; this restriction might have limited

the ability to perform certain massage techniques.

Nevertheless, the shifts towards less epidural

analgesia use and higher rates of analgesic-free

labour, in the absence of adverse labour outcomes,

support the efficacy of our massage programme.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated an overall shift towards

using weaker pain relief modalities among women

participating in an intrapartum massage programme.

The findings imply that massage, in combination

with controlled breathing and visualisation, may

modulate pain perception among labouring women,

leading to higher rates of analgesic-free labour.

Author contributions

Concept or design: CY Lai.

Acquisition of data: MKW Wong, WH Tong, SY Chu, KY Lau, AML Tam.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CY Lai, LL Hui.

Drafting of the manuscript: CY Lai, TTH Lao, TY Leung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: MKW Wong, WH Tong, SY Chu, KY Lau, AML Tam.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CY Lai, LL Hui.

Drafting of the manuscript: CY Lai, TTH Lao, TY Leung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Ms Linda Kimber, Midwife/Director, and

Ms Mary McNabb, Scientific Advisor and Academic Midwife,

both of Childbirth Essentials, Banbury, United Kingdom, for

training the midwives involved in the present study and for

advising the authors on the study design.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by The Joint Chinese University of

Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research

Ethics Committee (CREC Ref: 2016.332). The study has been registered

at the Centre for Clinical Research and Biostatistics, The

Chinese University of Hong Kong, (Unique Trial Number:

CUHK_CCRB00525; https://www2.ccrb.cuhk.edu.hk/registry/public/393). All participants were informed about the nature

of the study and provided written consent to participate

before randomisation into study groups.

References

1. Kabeyama K, Miyoshi M. Longitudinal study of the intensity of memorized labour pain. Int J Nurs Pract

2001;7:46-53. Crossref

2. Rijnders M, Baston H, Schönbeck Y, et al. Perinatal factors

related to negative or positive recall of birth experience

in women 3 years postpartum in the Netherlands. Birth

2008;35:107-16. Crossref

3. Rachmawati IN. Maternal reflection on labour pain management and influencing factors. Br J Midwifery

2012;20:263-70. Crossref

4. Yerby M. Managing pain in labour. Part 3: pharmacological

methods of pain relief. Mod Midwife 1996;6:22-5.

5. Cawthra AM. The use of pethidine in labour. Midwives Chron 1986;99:178-81.

6. Rajan L. The impact of obstetric procedure and analgesia/anaesthesia during labour and delivery on breastfeeding.

Midwifery 1994;10:87-103. Crossref

7. Jones L, Othman M, Dowswell T, et al. Pain management for women in labour: an overview of systematic reviews.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(3):CD009234. Crossref

8. Anim-Somuah M, Smyth RM, Cyna AM, Cuthbert A.

Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia for pain

management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;(5):CD000331. Crossref

9. Klomp T, van Poppel M, Jones L, Lazet J, Di Nisio M, Lagro-Janssen AL. Inhaled analgesia for pain management

in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(9):CD009351. Crossref

10. Thomson G, Feeley C, Moran VH, Downe S, Oladapo OT.

2019 Women’s experiences of pharmacological and non-pharmacological

pain relief methods for labour and

childbirth: a qualitative systematic review. Reprod Health

2019;16:71. Crossref

11. Chaillet N, Belaid L, Crochetière C, et al. Nonpharmacologic

approaches for pain management during labor compared

with usual care: a meta-analysis. Birth 2014;41:122-37. Crossref

12. Field T, Hemandez-Reif M, Taylor S, Quintino O, Burman I. Labor pain is reduced by massage therapy. J Psychosom

Obstet Gynecol 1997;18:286-91. Crossref

13. McCaffery M, Beebe A. Pain: clinical manual for nursing practice. J Pain Symptom Manage 1990;5:338-9. Crossref

14. Chang MY, Wang SY, Chen CH. Effects of massage on pain

and anxiety during labour: a randomized controlled trial in

Taiwan. J Adv Nurs 2002;38:68-73. Crossref

15. Karami NK, Safarzadeh A, Fathizadeh N. Effect of massage

therapy on severity of pain and outcome of labour in

primipara. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 2007;12:6-9.

16. Kimber L, McNabb M, Mc Court C, Haines A,

Brocklehurst P. Massage or music for pain relief in labour:

a pilot randomised placebo controlled trial. Eur J Pain

2008;12:961-9. Crossref

17. Janssen P, Shroff F, Jaspar P. Massage therapy and labor

outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Ther

Massage Bodywork 2012;5:15-20. Crossref

18. Mortazavi SH, Khaki S, Moradi R, Heidari K, Vasegh

Rahimparvar SF. Effects of massage therapy and presence

of attendant on pain, anxiety and satisfaction during

labour. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012;286:19-23. Crossref

19. Silva Gallo RB, Santana LS, Jorge Ferreira CH, et al. Massage

reduced severity of pain during labour: a randomised trial.

J Physiother 2013;59:109-16. Crossref

20. Mc Nabb MT, Kimber L, Haines A, McCourt C. Does

regular massage from late pregnancy to birth decrease

maternal pain perception during labour and birth? A

feasibility study to investigate a programme of massage,

controlled breathing and visualization, from 36 weeks

of pregnancy until birth. Complement Ther Clin Pract

2006;12:222-31. Crossref

21. Levett KM, Smith CA, Bensoussan A, Dahlen HG. Complementary therapies for labour and birth study:

a randomised controlled trial of antenatal integrative medicine for pain management in labour. BMJ Open

2016;6:e010691. Crossref

22. Bolbol-Haghighi N, Masoumi SZ, Kazemi F. Effect of massage therapy on duration of labour: a randomized

controlled trial. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:12-5. Crossref

23. Taghinejad H, Delphisheh A, Suhrabi Z. Comparison between massage and music therapies to relieve the severity

of labour pain. Womens Health (Lond) 2010;6:377-81. Crossref

24. Smith CA, Levett KM, Collins CT, Dahlen HG, Ee CC,

Suganuma M. Massage, reflexology and other manual

methods for pain management in labour. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2018;(3):CD009290. Crossref

25. Hui AS, Lao TT, Leung TY, Schaaf JM, Sahota DS. Trends

in preterm birth in singleton deliveries in a Hong Kong

population. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014;127:248-53. Crossref

26. The Royal College of Midwives. Childbirth essentials

towards natural childbirth and beyond. Available from:

https://www.rcm.org.uk/promoting/learning-careers/

accredited-learning/childbirth-essentials-towards-natural-childbirth-and-beyond/. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

27. Fuchs AR, Behrens O, Liu HC. Correlation of nocturnal

increase in plasma oxytocin with a decrease in plasma

estradiol/progesterone ratio in late pregnancy. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 1992;167:1559-63. Crossref

28. Tsui MH, Ngan Kee WD, Ng FF, Lau TK. A double blinded

randomised placebo-controlled study of intramuscular

pethidine for pain relief in the first stage of labour. BJOG

2004;111:648-55. Crossref

29. Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

Report of the territory-wide audit in obstetrics &

gynaecology. 2014. Available from: https://www.hkcog.org.hk/hkcog/pages_4_307.html. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.