© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

secondary to dengue fever: a case report

SW Cheo, MRCP (UK)1; WNFA Abdul Rashid, MB, BS (UM)1; CV Ho, MPath (UPM)2; Rosdina Z Ahmad Akhbar, MMed (UiTM)1; QJ Low, MRCP (UK)3; Giri S Rajahram, FRCP (UK)4

1 Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Lahad Datu, Sabah, Malaysia

2 Department of Pathology, Hospital Queen Elizabeth, Sabah, Malaysia

3 Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Sultanah Nora Ismail, Johor, Malaysia

4 Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Queen Elizabeth, Sabah, Malaysia

Corresponding author: Dr SW Cheo (cheosengwee@gmail.com)

Case presentation

A 30-year-old man with underlying microcytic

hypochromic anaemia presented to a local health

clinic with a 3-day history of fever and 1-day

history of arthralgia, myalgia, abdominal pain, and

vomiting. On presentation, he was hypotensive

at 84/50 mm Hg and tachycardic with pulse rate

118 beats per minute. He responded well to fluid

resuscitation and was referred to hospital. Upon

arrival, he was alert with normal Glasgow Coma

Scale score, blood pressure 126/82 mm Hg, pulse

rate 126 beats per minute and temperature 37.7°C.

Examination revealed jaundiced, cold peripheries,

poor pulse volume, and a capillary refill time >2 s.

Respiratory examination showed crepitations over

the lung bases bilaterally. Systemic examination was

otherwise unremarkable.

His initial full blood count revealed

haemoglobin of 9.8 g/dL, white cell count

6.37 × 109/L, and platelet count of 30 × 109/L. He had

a deranged renal profile with sodium 134 mmol/L,

potassium 5.2 mmol/L, urea 11.6 mmol/L, and creatinine 211 μmol/L. He was also acidotic with

pH 7.39 and bicarbonate 14.3 mmol/L. Liver function

biochemistry showed elevated transaminases,

alanine aminotransferase 1114 U/L, aspartate

aminotransferase 1816 U/L, and lactate 5.26 mmol/L

(Table). He tested positive for dengue NS-1 and

negative for dengue immunoglobulin M and

immunoglobulin G. Blood smear for malaria parasite

and Leptospira immunoglobulin M was negative. He

was diagnosed with severe dengue, decompensated

shock, and multiorgan failure.

He was admitted to the intensive care unit

and treated with fluid resuscitation and blood

transfusion. Despite prompt initial resuscitation,

his clinical response was poor with further

deterioration in organ function. Elective intubation

and urgent haemodialysis were performed but

he collapsed prior to completion of the dialysis

session. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

(HLH) was suspected in view of the multiorgan

failure and rapid clinical deterioration. Workup

revealed hypertriglyceridaemia of 8.7 mmol/L and hyperferritinaemia of >40 000 mg/L. Abdominal

ultrasound showed splenomegaly. There was no

family history of HLH. Unfortunately, he deteriorated

further and progressed to disseminated intravascular

coagulation, succumbing on day 3 of admission due

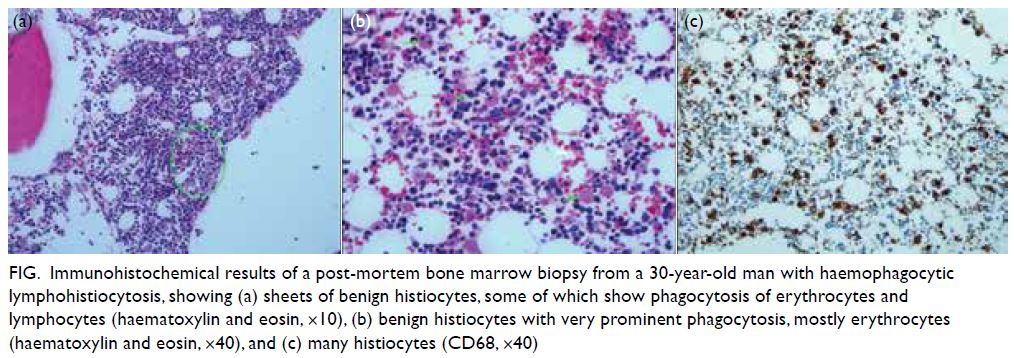

to multiorgan failure. Histopathological examination

of post-mortem bone marrow trephine biopsy

confirmed the diagnosis of HLH (Fig). His dengue

polymerase chain reaction test was later reported to

be positive for DEN3 infection.

Figure. Immunohistochemical results of a post-mortem bone marrow biopsy from a 30-year-old man with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, showing (a) sheets of benign histiocytes, some of which show phagocytosis of erythrocytes and lymphocytes (haematoxylin and eosin, ×10), (b) benign histiocytes with very prominent phagocytosis, mostly erythrocytes (haematoxylin and eosin, ×40), and (c) many histiocytes (CD68, ×40)

Discussion

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is a rare but

potentially life-threatening condition caused by

overactive immune activation. It was first described

by Farquhar and Claireaux in 1952.1 Broadly, it

can be divided into primary and secondary HLH.

Primary HLH typically manifests in children with

genetic abnormalities of natural killer cells and

T cells. Secondary HLH is often associated with

various infections that may be viral, bacterial,

fungal or parasitic, and connective tissue disorders

or malignancies, particularly T cell lymphoma.2

Dengue fever is a viral infection that can trigger

secondary HLH. In recent years, more reports

of dengue-associated HLH have emerged. It is

important for clinicians to recognise this entity

because it is associated with considerable mortality

and morbidity.

Dengue fever is an arboviral disease caused

by dengue virus, a virus of the Flaviviridae group.

Worldwide, it is endemic in more than 100 countries.

The World Health Organisation has estimated

there to be 390 million dengue infections annually

with 96 million manifesting clinically. It usually

presents with fever, myalgia, arthralgia, eye pain,

and headache. Around 5% of patients will progress

to severe dengue, characterised by plasma leakage,

hypovolaemic shock, haemorrhage, organ failure,

and encephalopathy.3 Some patients with severe

dengue will develop HLH.

Dengue is an uncommon cause of HLH,

but it should be suspected in patients with

unexplained systemic inflammatory response

syndrome such as prolonged fever, cytopenias,

malaise, and hepatosplenomegaly. Ongoing fever

after 8 days of illness should alert clinicians to

the possibility of HLH.4 Laboratory findings will

show cytopenia, raised ferritin, triglyceride, liver

impairment, hypofibrinogenaemia, and raised

lactate dehydrogenase. The diagnosis of HLH can be

established in the presence of a molecular diagnosis

consistent with HLH or the presence of five out

of eight criteria: fever >38.5°C; splenomegaly;

peripheral blood cytopenias; hypertriglyceridaemia;

hypofibrinogenaemia; haemophagocytosis in bone

marrow, spleen or liver; hyperferritinaemia

(>500 ng/mL); and increased CD25/interleukin-2

receptor or reduced natural killer cell function.4

The hallmark of diagnosis is observation of

haemophagocytosis in the tissue. Molecular

diagnosis consistent with HLH includes pathologic

mutations of PRF1, UNC13D, Munc18-2, Rab27a,

STX11, SH2D1A, or BIRC4.

Pathophysiologically, viral infection of T

cells leads to overproduction of cytokines such

as tumour necrosis factor alpha and interferon

gamma and can lead to uncontrolled histiocytic

activity. The consequent cytokine storm can lead

to organ dysfunction and death. To date, only three

serotypes of dengue virus (DEN1, DEN3 and DEN4)

are known to cause HLH. Our patient fulfilled

six of the HLH diagnostic criteria: having fever,

splenomegaly, cytopenias, hypertriglyceridaemia,

hyperferritenaemia, and haemophagocytosis in the

bone marrow. He also exhibited raised bilirubin,

liver enzymes and raised lactate dehydrogenase,

and developed acute renal failure that required

haemodialysis. Unfortunately, he became

haemodynamically unstable during dialysis and

eventually succumbed to his illness. Fibrinogen and

CD25 levels were not measured as the tests were not

available in our centre.

In the absence of treatment, dengueassociated

HLH carries a high mortality.5 Essentially,

it is important to suspect and diagnose the clinical

syndrome early so that appropriate treatment

can be given. In general, management of dengue-associated

HLH includes standard fluid protocols

and HLH-directed therapy. Dexamethasone and

etoposide can be given as HLH-directed therapy

to suppress the overactive immune response. The

exact mechanism of etoposide in hyperinflammation

is not well understood but it has been shown to

alleviate symptoms of all murine HLH.5 As well

as corticosteroid and etoposide, intravenous

immunoglobulin and antithymocyte globulin have

also been tried. However, clinicians should remain

vigilant when administering HLH-directed therapy

in the setting of concomitant sepsis.

Conclusion

Dengue-associated HLH is an important and unique

entity. We believe that it is very much underreported

due to failed recognition of the entity. The hallmark

of this disease is an overactive immune response and

presence of haemophagocytosis. Dengue-associated

HLH can be diagnosed by HLH criteria and HLH-directed

therapy initiated.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: SW Cheo.

Analysis or interpretation of data: SW Cheo, CV Ho, RZ Ahmad Akhbar, QJ Low.

Drafting of the manuscript: SW Cheo, WNFA Abdul Rashid, QJ Low.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: SW Cheo.

Analysis or interpretation of data: SW Cheo, CV Ho, RZ Ahmad Akhbar, QJ Low.

Drafting of the manuscript: SW Cheo, WNFA Abdul Rashid, QJ Low.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Tan Sri Dato' Seri Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah, the Director General of Health Malaysia

for his permission to publish this article.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration

of Helsinki. The patient provided informed consent for all

treatments and procedures, and the patient’s brother provided

consent for publication.

References

1. Farquhar JW, Claireaux AE. Familial haemophagocytic

reticulosis. Arch Dis Child 1952;27:519-25. Crossref

2. Ray U, Dutta S, Mondal S, Bandyopadhyay S. Severe dengue

due to secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a

case study. IDCases 2017;8:50-3. Crossref

3. Ellis EM, Sharp TM, Pérez-Padilla J, et al. Incidence and risk

factors for developing dengue-associated hemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis in Puerto Rico, 2008-2013. PLoS Negl

Trop Dis 2016;10:e0004939. Crossref

4. Koshy M, Mishra AK, Agrawal B, Kurup AR, Hansdak SG.

Dengue fever complicated by hemophagocytosis. Oxf Med

Case Reports 2016;2016:121-4. Crossref

5. Kan FK, Tan CC, Greenwood TVB, et al. Dengue infection

complicated by hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis:

experiences from 180 patients with severe dengue. Clin

Infect Dis 2020;70:2247-55. Crossref