Hong Kong Med J 2022 Feb;28(1):45–53 | Epub 23 Jul 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Questionnaire survey on knowledge, attitudes,

and behaviour towards viral hepatitis among the Hong Kong public

Henry LY Chan, MD1,2; Grace LH Wong, MD1,3,4,5; Vincent WS Wong, MD1,3,4,5; Martin CS Wong, 1,6; Carol YK Chan, PhD7; Shikha Singh, PhD8

1 Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Internal Medicine, Union Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

4 Medical Data Analytic Centre (MDAC), The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

5 Institute of Digestive Disease, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

6 JC School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

7 Gilead Sciences, Hong Kong

8 Kantar Health, Singapore

Corresponding author: Dr Henry LY Chan (hlychan@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: We aimed to identify gaps in

knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours towards viral

hepatitis among the Hong Kong public and provide

insights to optimise local efforts towards achieving

the World Health Organization’s viral hepatitis

elimination target.

Methods: A descriptive, cross-sectional, self-reported

web-based questionnaire was administered

to 500 individuals (aged ≥18 years) in Hong Kong.

Questionnaire items explored the awareness and

perceptions of viral hepatitis-related liver disease(s)

and associated risk factors in English or traditional

Chinese.

Results: The majority (>80%) were aware that

chronic hepatitis B and/or C could increase the

risks of developing liver cirrhosis, cancer, and/or

failure. Only 55.8% had attended health screenings

in the past 2 years, and 67.6% were unaware of their

family’s history of liver diseases. Misperceptions

surrounding the knowledge and transmission

risks of viral hepatitis strongly hint at the presence

of social stigmatisation within the community.

Many misperceived viral hepatitis as airborne or

hereditary, and social behaviours (casual contact or

dining with an infected person) as a transmission

route. Furthermore, 62.4% were aware of hepatitis B

vaccination, whereas 19.0% knew that hepatitis C

cannot be prevented by vaccination. About 70%

of respondents who were aware of mother-to-child

transmission were willing to seek medical

consultation in the event of pregnancy. Gaps in knowledge as well as the likelihood of seeking

screening were observed across all age-groups and

education levels.

Conclusions: Comprehensive hepatitis education

strategies should be developed to address gaps in

knowledge among the Hong Kong public towards

viral hepatitis, especially misperceptions relevant

to social stigmatisation and the importance of

preventive measures, including vaccination and

screening, when exposed to risk factors.

New knowledge added by this study

- General awareness of potential risks of viral hepatitis developing into liver cirrhosis, cancer, or liver failure.

- Many still had misperceptions in terms of knowledge and transmission risk of viral hepatitis, suggestive of social stigma or discrimination towards infected individuals.

- Gaps in knowledge about viral hepatitis and likeliness to seek medical screening were observed across all age-groups, especially in respondents with secondary or higher education.

- We emphasise the importance of preventive measures including screening, diagnosis, treatment, and care to effectively manage viral hepatitis in Hong Kong.

- It is essential to develop universal education strategies to address misperceptions relevant to social stigmatisation, aligning with the community’s preferences for various information media channels to optimise information reception.

Introduction

Viral hepatitis is a major public health burden

worldwide and is the predominant aetiology of liver

cirrhosis and/or liver cancer.1 2 At least 325 million

individuals were reported to be infected with

viral hepatitis B (HBV) and/or C (HCV).2 3

Hong Kong is considered an endemic area with

intermediate incidence of HBV infection.4 In a local

epidemiological study conducted between 2015

and 2016, the seroprevalence of hepatitis B surface

antigen (HBsAg) was estimated at 7.8% among the

general population.5 In contrast, the prevalence rate

of HCV infection in Hong Kong has remained low.6

The seroprevalence of anti-HCV positivity among

new blood donors was 0.06% in 2017, compared with

0.11% in 2008.6 The local HCV prevalence among

the general population between 2015 and 2016 was

estimated at 0.5%,5 which has remained relatively unchanged since 1992.7

In 2016, the World Health Organization

(WHO) implemented a global elimination strategy

targeted to achieve at least a 90% diagnosis rate

of all viral hepatitis cases, an 80% treatment rate

for all diagnosed cases, and a 90% reduction in

the incidence of viral hepatitis cases.3 Recent

epidemiological studies in Hong Kong revealed that

the diagnosis and treatment uptake rates within

the community were significantly lacking, hovering

around 50% compared with the WHO’s 90%/80% targets.5 8 It has been suggested that inadequate

knowledge and awareness about viral hepatitis B and

C within Hong Kong’s community might be driving

this deficiency.5 8 9 10 In other parts of the world,

social stigma arising from poor knowledge has been

reported to reduce diagnosis and treatment rates

among high-risk individuals.11 12 13

In 2020, the Hong Kong Viral Hepatitis

Action Plan (HKVHAP) 2020-2024 was launched

to facilitate achieving the WHO’s eradication

target goals by 2030. The action plan outlined four

major strategies: (1) Awareness, (2) Surveillance,

(3) Prevention, and (4) Treatment to monitor and

implement local efforts towards achieving the

WHO’s 2030 elimination target.14

In the present study, we aimed to explore

the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour within

Hong Kong’s general population pertaining to viral

hepatitis and related risk factors. Furthermore, in

this study, we sought to identify potential gaps in

existing knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour related

to the WHO’s global viral hepatitis elimination

strategy to optimise local efforts towards the WHO’s

target goal.

Methods

Study population

Potential respondents were recruited through an

existing, general purpose (ie, not healthcare-specific)

web-based consumer panel via email in February

2020. Respondents who were aged ≥18 years,

had access to online or comfort with web-based

administration, and were able to read English or

traditional Chinese were eligible to participate in

the study. There were no exclusion criteria for this

study. All eligible respondents explicitly agreed to

join the panel and provided informed online consent

to participate in the study.

Assuming 95% confidence intervals and 50%

response distribution, responses collected from

500 adult individuals were deemed sufficient to

provide descriptive estimates with 4.33% margin of

error.

Study design

Items pertaining to awareness and perceptions

of liver diseases among the general public were

explored using a self-administered web-based

survey. The survey questionnaire was developed

in English and translated into traditional Chinese.

The translation was validated by a linguist from a

translation company who is a native speaker of the

language. The developed questionnaire was reviewed

and finalised by a steering committee comprising

gastroenterology and/or hepatology experts from

11 countries/territories as part of a regional liver

index study (Lee Mei-hsuan et al, unpublished). All respondents completed the questionnaire in either

English or Chinese. Only de-identified data were

collected.

Survey questionnaire

The internal consistency of the questionnaire from the regional liver index study was assessed by

Cronbach’s alpha (threshold: alpha >0.7). As part

of this study’s objective to explore the knowledge,

attitudes, and behaviour of Hong Kong’s public

towards viral hepatitis-related liver diseases, seven

items were extracted from the questionnaire used in

a regional liver index study. These items pertained

to the awareness and knowledge of liver diseases as

well as the respondents’ attitudes and behaviours

towards screening and diagnosis of liver diseases

(online supplementary Appendix 1; Q1-7).

Seven screener questions (online

supplementary Appendix 1; S1-7) pertaining to the

respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics,

including age, sex, education, monthly household

income, and their awareness of different types of

hepatitis were also included in this study.

Respondents who indicated their awareness

of ‘hepatitis B’ or ‘hepatitis C’ in screener item S7

proceeded to answer Q1(I)-Q2(I) or Q1(II)-Q2(II).

Female respondents who correctly recognised the

statement ‘from a pregnant mother to her baby’ in

Q2f(I) or Q2f(II) proceeded to answer Q3c.

Descriptive analysis

This study was exploratory and descriptive in nature. Respondents’ characteristics and responses

to the survey questions were summarised and

are presented as frequencies and percentages. No

statistical analyses were performed.

Missing data were random; all data were

reported, including those of respondents who

declined to answer certain screener questions, such

as on monthly household income. Missing data for

any question were excluded from analysis of that

question only, not from the whole study.

Results

Study population characteristics

Among the respondents, 68.0% were aged ≥35 years,

and 56.0% were female. Among the respondents,

59.0% had completed university or higher education,

and 76.0% possessed private insurance. About 70%

of respondents had a monthly household income of

≥HK$30 000. The respondents’ sex, age, education

level, and household income were reflective of Hong

Kong’s population.15 Approximately half of the

respondents (55.8%) self-reported having attended

health screenings within the last 2 years, and about

32.4% of them were aware of their family history

pertaining to liver diseases (Table 1).

General knowledge and awareness of

hepatitis B and C

A higher proportion of respondents were aware of

hepatitis B (93.0%, 465/500) than hepatitis C (46.4%,

232/500) [online supplementary Appendix 2]. The

majority (>80%) were aware that hepatitis B and

C can cause liver failure and increase the risks of

developing liver cirrhosis and liver cancer (Fig 1a).

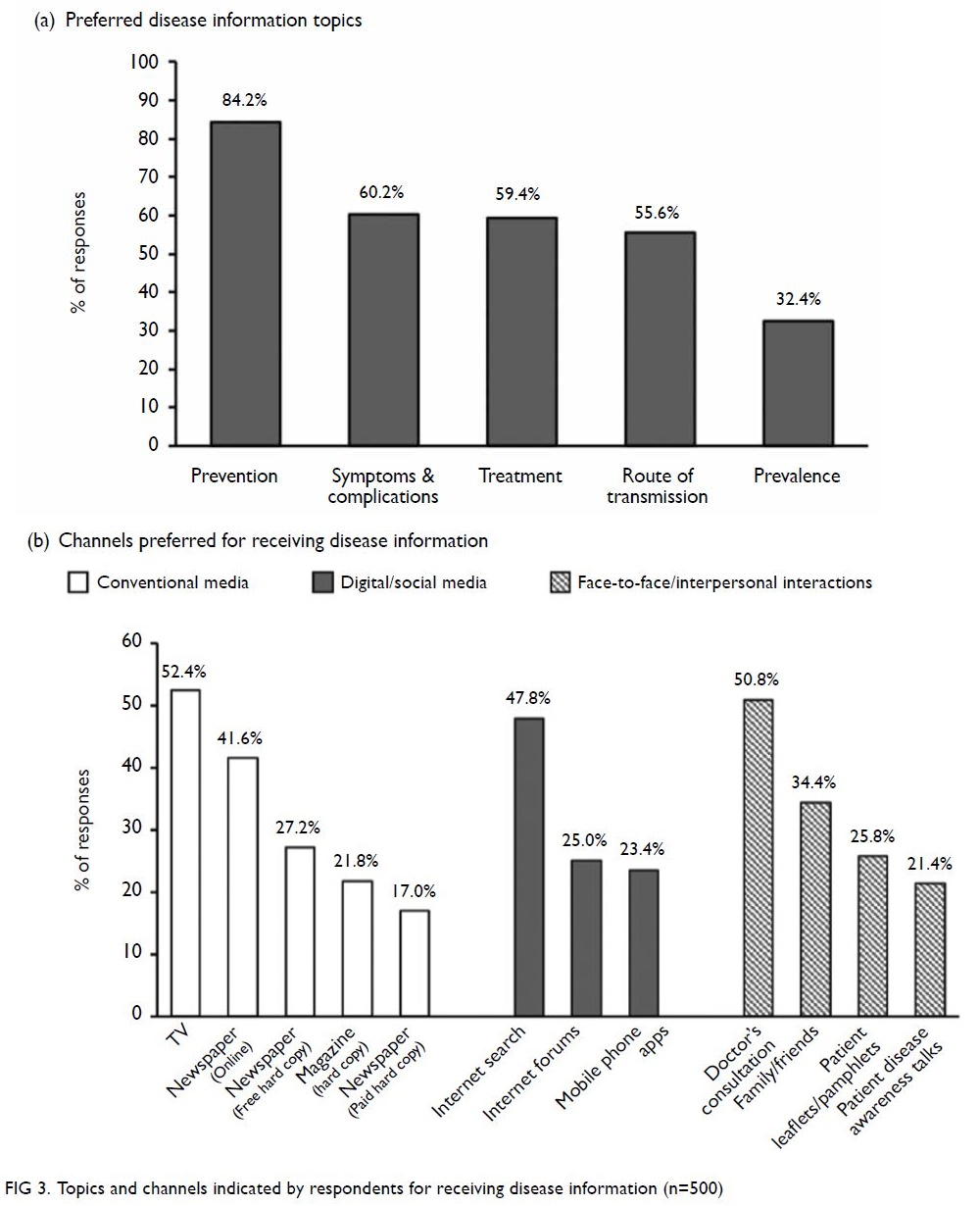

Figure 1. Proportion of respondents who correctly identified the features and transmission risks of hepatitis B and C

About 60% of respondents who were aware of

hepatitis B knew that HBV is not airborne (61.5%)

and can be prevented by a vaccine (62.4%). Only

approximately 40% (186/465) of the respondents

were aware that hepatitis B is not hereditary (Fig 1a).

In contrast, only 19.0% (n=44/232) of those aware

of hepatitis C knew that it cannot be prevented by

vaccination, and about half knew that it is neither

airborne (54.3%) nor hereditary (41.8%) [Fig 1a].

About half of the respondents aged <25 years

(58.2%) and 55 to 64 years (46.9%) were not aware

that hepatitis B is preventable by vaccination. More

than half of the respondents across all age-groups were unaware that hepatitis B is not hereditary,

with the highest proportion aged <25 years (80.0%).

A substantial proportion of respondents (>35%)

with either secondary or university education

misperceived hepatitis B to be airborne (38.5%;

39.8%) or hereditary (62.0%; 59.7%) [online supplementary Appendix 3].

More than 70% of respondents across all age-groups and >80% with secondary school or university

education misperceived that a vaccine could prevent

hepatitis C. About half of subjects aged 25 to 44 years

and ≥65 years were not aware that hepatitis C is

not airborne, whereas >70% of those aged 25 to

34 years and ≥65 years misperceived hepatitis C

to be hereditary. More than half of respondents

with university (61.0%) or postgraduate (51.9%)

education misperceived hepatitis C as hereditary

(online supplementary Appendix 4).

Knowledge about the transmission risks of

hepatitis B and C

At least 30% of respondents rightly perceived that

(1) touching an infected person (HBV: 29.9%; HCV:

31.5%), (2) the faecal-oral route (21.9%; 28.4%); or (3)

dining with an infected person (42.2%; 38.4%) were

not possible modes of transmission of viral hepatitis

B and C (Fig 1b). More than half of the respondents

were aware of the mother-to-child transmission risk

of HBV (68.4%) and HCV (53.9%) [Fig 1b]. Awareness

of other transmission modes of HBV and HCV are

detailed in online supplementary Appendix 2.

More than 60% of respondents across all age-groups and those with at least secondary school

education did not correctly identify the transmission

risks of HBV (online supplementary Appendix 5):

more than half with secondary or university

education misperceived touching (73.3%; 70.4%) or

dining with an infected person (60.4%; 56.2%) as

HBV transmission risks.

With regard to hepatitis C, more than half of

the respondents aged ≥35 years and at least 60% of

individuals with at least secondary-level education

were unaware or incorrectly identified with the

statements regarding social interaction and food

contamination as HCV transmission risks. Notably,

no respondents with the primary school education

level were aware of hepatitis C (online supplementary Appendix 6).

Likelihood of attending health screening in

the event of family planning

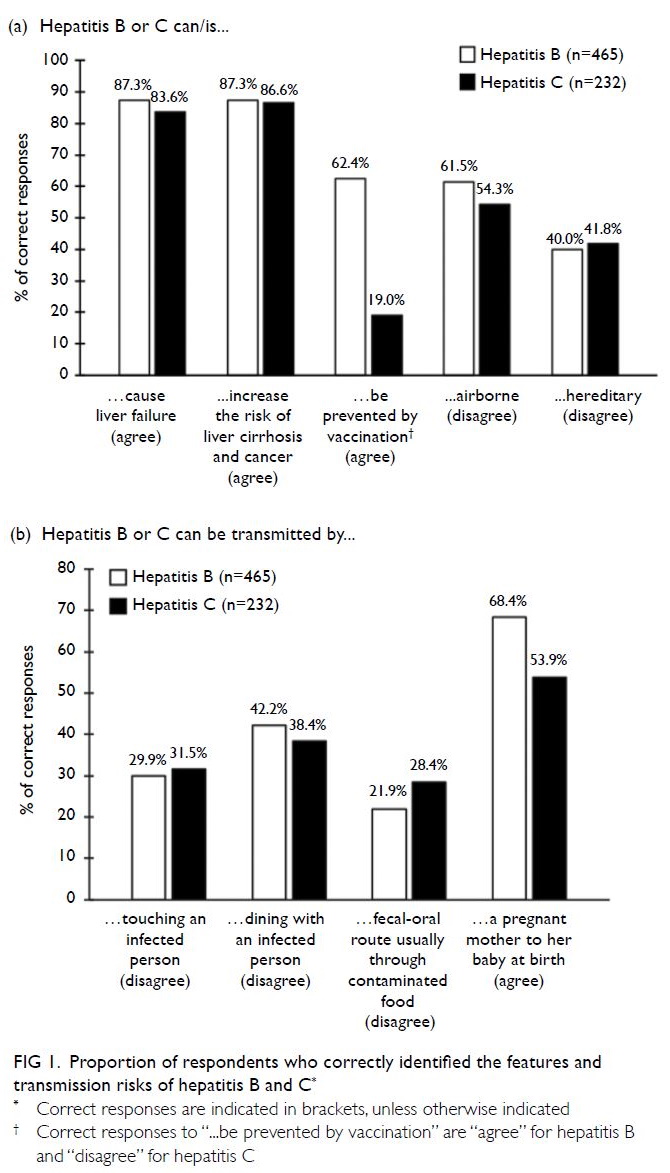

Among the 280 female respondents, 65% correctly identified mother-to-child transmission as a

transmission risk of viral hepatitis B and/or C

(Fig 2). Among these respondents, 70.3% expressed

that they were extremely likely or likely to seek a

doctor’s consultation to get tested if they were or

intended to become pregnant (Fig 2).

Figure 2. Respondents’ self-reported likelihood of seeking doctor’s consultation in the event of pregnancy (n=182)

About one-fifth of the respondents with

university (25.3%) or postgraduate (21.4%) education

indicated that they were unlikely (neutral, unlikely,

or extremely unlikely) to get tested for viral hepatitis

in the event of pregnancy planning. About 40% of

the respondents aged <25 years (46.7%) expressed

that they were unlikely to seek screening if they

wanted to become or became pregnant (Table 2).

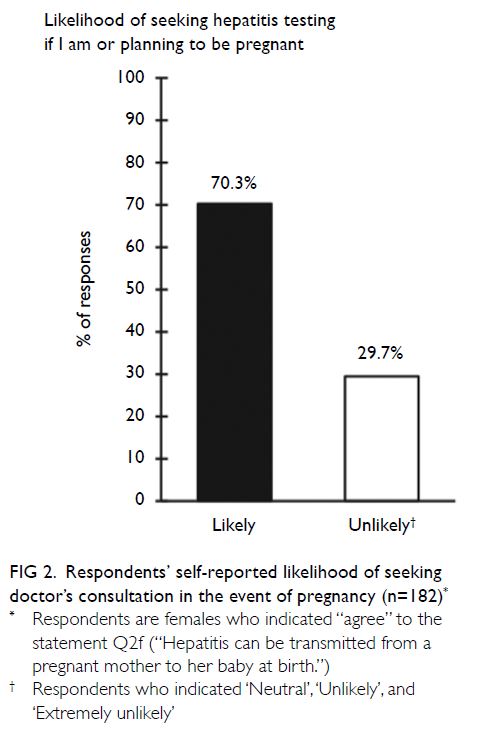

Table 2. Characteristics of respondents who indicated their likelihood of seeking viral hepatitis testing/screening

Preferred disease information topics and

channels

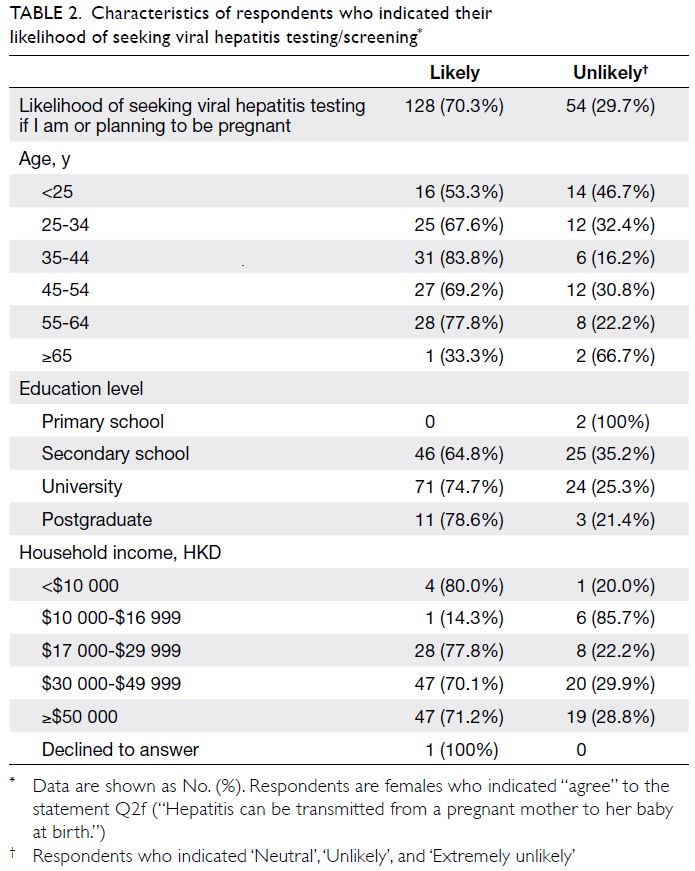

The top three disease information topics that

the respondents stated that they would like to

understand more were disease prevention (84.2%),

disease symptoms and complications (60.2%), and

treatment (59.4%) [Fig 3a].

Among the various information dissemination

channels, about half of the respondents preferred

TV (conventional media [52.4%]), internet

search (digital/social media [47.8%]) and doctor’s

consultation (face-to-face/interpersonal interactions

[50.8%]) [Fig 3b].

Discussion

There was an improved general awareness (>80%)

about the sequelae of HBV and HCV compared with that observed in 2010 (>70%).16 However, a

substantial proportion (>60%) of respondents across

all age-groups and education levels in Hong Kong

held misconceptions about HBV and HCV and their

transmission risks.

The local awareness of HBV vaccination

among Hong Kong respondents (62.4%) was higher

than that of Nigeria (31.9%)17 but lower than that

of Singapore (75.1%).18 Among those unaware of

hepatitis B vaccination in Hong Kong, the majority

were aged ≥25 years. This is concerning because

these respondents were born before the rollout of

the local vaccination programme in 1988. Extensive

global and local studies have reported that the

implementation of HBV vaccination effectively

reduced the incidence and seroprevalence of HBV-associated

viral hepatitis.3 6 14 19 20 A recent study

in Nigeria showed a relationship between HBV

vaccination and knowledge about viral hepatitis,17

suggesting an unmet need to improve knowledge

about HBV to increase HBV vaccination uptake,

particularly in older adults.

Moreover, in this study, we observed a general

local misperception that a vaccine is available

for HCV, which has been similarly observed

globally,18 21 although we observed a slightly higher

local awareness rate (19.0%) than that in Singapore

(15.0%).18 This lack of awareness pertaining to HCV

might impede the adoption of correct preventive

measures against hepatitis C infection.22

Both the WHO’s hepatitis elimination

strategy and HKVHAP 2020-2024 emphasised the

importance of combating any forms of stigmatisation

or discrimination in the implementation of

awareness and communication strategies to improve

health outcomes among high-risk individuals.3 14

Social stigmatisation and discrimination stem from

the lack of knowledge within society12 23 and among healthcare practitioners.10 Misperceptions such

as the idea that hepatitis can be spread by sharing

of food or eating utensils, the faecal-oral route, or

touching an infected person (perceived by >60% of

the study’s respondents) often underlie the social

stigmatisation surrounding viral hepatitis.16 18 23 24

These often result in the avoidance of casual contact,

self-isolation,11 23 or denial of potential employment

or professional advancement,25 26 as experienced

by infected individuals across the world. Many

respondents without HBV infection in China

expressed discomfort about being in close contact

or sharing meals with HBV-infected individuals

and felt that they should not be allowed to work

in restaurants or with children.25 Similarly, 55.2% respondents in a 2019 Korean survey thought HCV

patients should use separate towels and dishes,27 which is an indication of the misperception of HCV

transmission by causal contact.

Over time, these social behaviours arising from

misperceptions could result in a paradox for those

infected with viral hepatitis, as stigma and shame

could lead them to conceal their condition and

avoid seeking the necessary medical treatment.26 28

Therefore, there is a need to adopt a comprehensive

approach to raise community awareness and

knowledge to tackle stigmatisation against infected

individuals.

The belief that viral hepatitis is hereditary (ie, it could be inherited through ‘bad genes’29) could

potentially result in the misunderstanding that there

are no preventive measures against viral hepatitis. In

fact, mother-to-child transmission is a major route

of hepatitis B transmission in Asia. The potential

confusion between a vertically transmitted disease

and a hereditary one could impede efforts to reduce

community transmission of viral hepatitis, as many

might not bother to find out more information or

proactively seek screening.

The HBsAg seropositivity screening during

pregnancy and neonatal vaccination are integral

parts of HKVHAP and the WHO’s hepatitis

elimination strategy to prevent mother-to-child

transmission.3 14 Prevention of perinatal transmission

of HBV in Hong Kong includes an additional viral

load screening of HBsAg-seropositive mothers to

guide maternal antiviral therapy. Approximately

70% of pregnant women in Hong Kong (between

May 2017 and December 2019) reportedly did not

undergo viral load testing or regular hepatological

surveillance before pregnancy.30 This is an important

public health issue, as viral load in mothers who

are hepatitis B carriers is a key influencing factor of

immunoprophylaxis success in their babies.31 Among

the 280 female respondents, only 128 (45.7%) were

aware of the risk of mother-to-child transmission

and likely to seek medical consultation in the event

of pregnancy, suggesting a gap in women’s awareness and knowledge about viral hepatitis in Hong Kong.

Besides vertical transmission, horizontal

spread is also an important means of HBV infection.

In this study, 67.6% of respondents were unaware of

their family’s history of liver disease(s), and only 50%

knew that sexual contact is a transmission risk of HBV

and HCV (online supplementary Appendix 2). This

suggests an unmet need to educate the community

about not only mother-to-child transmission, but

also other transmission risks. More robust education

efforts are needed to raise the population’s level of

knowledge and awareness about viral hepatitis

to work towards the WHO’s elimination goal.

Such outreach efforts could be aligned with the

respondents’ preferences for information media

channels such as TV, internet search, and doctor’s

consultation to optimise community reception.

This study has some limitations. Being a self-administered

cross-sectional study based on self-reported

data, the study is subject to recall bias. As

such, data validation could not be performed, and

no causal associations could be made. Respondents

who lack internet access or comfort with online

administration could be underrepresented.

Furthermore, this study did not consider factors that

could influence respondents’ levels of knowledge

and/or awareness or attitudes towards HBV and

HCV (eg, respondents’ health consciousness or

vaccination or hepatitis status). With <60% having

attended a health screening in the past 2 years

and <70% expressing a high likelihood of medical

consultation when exposed to risk factors, it would

be insightful to explore the reasons for these gaps

in proactive health-seeking behaviours. This would

facilitate addressing and dispelling concerns to

promote precautionary measures and health-seeking

behaviours to reduce community transmission.

As this study is exploratory and descriptive

in nature, statistical analyses were not performed

to evaluate factors associated with the gaps in

knowledge, awareness, and/or practices pertaining

to hepatitis B and C; thus, the associations of

respondents’ characteristics could not be identified

in this study. Additional analyses would be warranted

in future studies to confirm any independent factors

associated with the community’s levels of knowledge

and awareness.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that respondents had a

general awareness of hepatitis B and C. However, our

findings revealed gaps in respondents’ knowledge

and understanding of the transmission risks of

hepatitis B and C as well as awareness of their family

history related to liver disease(s). The findings

suggest that there may be social stigmatisation or

discrimination against people with HBV and HCV within the community, which may deter some from

undergoing screening and diagnosis.

It is essential to develop targeted education

strategies with special attention towards addressing

misperceptions relevant to social stigmatisation

or discrimination and raise the importance of

preventive measures such as vaccination and

screening when exposed to risk factors. Outreach

of such targeted education efforts should be aligned

with the community’s preferred information

channels to maximise information accessibility.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: S Singh.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: S Singh.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

HLY Chan is an advisor to AbbVie, Aligos, Arbutus, Gilead

Sciences, GSK, Hepion, Janssen, Merck, Roche, Vaccitech,

Venatorx, and Vir Biotechnology; and a speaker for Gilead

Sciences, Mylan, and Roche.

GLH Wong has served as an advisory committee

member for Gilead Sciences; as a speaker for Abbott, Abbvie,

Bristol-Myers Squibb, Echosens, Furui, Gilead Sciences,

Janssen and Roche; and received a research grant from Gilead

Sciences.

VWS Wong served as a consultant or advisory board

member for 3V-BIO, AbbVie, Allergan, Boehringer Ingelheim,

the Center for Outcomes Research in Liver Diseases,

Echosens, Gilead Sciences, Hanmi Pharmaceutical, Intercept,

Inventiva, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Perspectum

Diagnostics, Pfizer, ProSciento, Sagimet Biosciences,

TARGET PharmaSolutions, and Terns; and a speaker for

AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Echosens, and Gilead Sciences.

He has received a grant from Gilead Sciences for fatty liver

research. He is also a Co-founder of Illuminatio Medical

Technology Limited.

As an editor of the Journal, MCS Wong was not involved in the peer review process for this article.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge valuable support from Dr Vince

Grillo of Kantar Health overseeing the development of the

project. The authors thank Dr Amanda Woo of Kantar Health

for providing medical writing and editorial support, which

was funded by Gilead Sciences, Hong Kong, in accordance

with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3). The translation of the questionnaire

from English to traditional Chinese was performed by

GlobaLexicon Limited, United Kingdom and funded by Gilead

Sciences, Hong Kong. The authors acknowledge the members

of the steering committee for their contribution in reviewing

and finalising the questionnaire: Dr Mei-hsuan Lee, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University (Taiwan); Dr Sang-hoon

Ahn, Yonsei University College of Medicine (South Korea);

Dr Henry LY Chan, Union Hospital (Hong Kong); Dr Asad

Choudhry, Chaudhry Hospital (Pakistan); Dr Rino Alvani

Gani, University of Indonesia (Indonesia); Dr Rosmawati

Mohamed, University of Malaya (Malaysia), Dr Janus P Ong,

University of the Philippines (Philippines); Dr Akash Shukla,

King Edward Memorial Hospital, Global Hospital (India); Dr

Chee-kiat Tan, Singapore General Hospital (Singapore); Dr

Tawesak Tanwandee, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University

(Thailand); and Dr Pham-thi Thu Thuy, Ho Chi Minh Medic

Medical Center (Vietnam).

Funding/support

This study was funded by Gilead Sciences, Hong Kong. Kantar Health, Singapore, received funding from Gilead Sciences,

Hong Kong, for the conduct of the study and development of

the manuscript.

Ethics approval

All eligible respondents explicitly agreed to join the panel and provided informed online consent to participate in the study.

References

1. Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol 2019;70:151-71. Crossref

2. World Health Organization. Hepatitis in the Western Pacific. Available from: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/health-topics/hepatitis. Accessed 3 Aug 2020.

3. World Health Organization. Global Health Sector

Strategy on Viral Hepatitis, 2016-2021: towards ending

viral hepatitis. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/246177/WHO-HIV-2016.06-eng.pdf;jsessionid=F5934335456A761C7349258535E3E5EC?sequence=1. Accessed 14 Dec 2020.

4. Lin AW, Wong KH. Surveillance and response of hepatitis B

virus in Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, 1988-2014. Western Pac Surveill Response J 20163;7:24-8. Crossref

5. Liu KS, Seto WK, Lau EH, et al. A territory-wide prevalence

study on blood-borne and enteric viral hepatitis in Hong

Kong. J Infect Dis 2019;219:1924-33. Crossref

6. Viral Hepatitis Control Office, Special Preventive

Programme, Centre for Health Protection, Department of

Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Surveillance of viral

hepatitis in Hong Kong—2017 update report. Available

from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/viral_hepatitis_report.pdf. Accessed 14 Jan 2021.

7. Chan GC, Lim W, Yeoh EK. Prevalence of hepatitis C infection in Hong Kong. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1992;7:117-20. Crossref

8. Hui YT, Wong GL, Fung JY, et al. Territory-wide

population-based study of chronic hepatitis C infection

and implications for hepatitis elimination in Hong Kong.

Liver Int 2018;38:1911-9. Crossref

9. Lao TT, Sahota DS, Suen SS, Lau TK, Leung, TY. Chronic

hepatitis B virus infection and rubella susceptibility in

pregnant women. J Viral Hepat 2010;17:737-41. Crossref

10. Paterson BL, Backmund M, Hirsch G, Yim C. The depiction of stigmatization in research about hepatitis C. Int J Drug

Policy 2007;18:364-73. Crossref

11. Zacks S, Beavers K, Theodore D, et al. Social stigmatization and hepatitis C virus infection. J Clin Gastroenterol

2006;40:220-4. Crossref

12. Mokaya J, McNaughton AL, Burbridge L, et al. A blind

spot? Confronting the stigma of hepatitis B virus (HBV)

infection—a systematic review. Wellcome Open Res

2018;3:29. Crossref

13. Marinho RT, Barreira DP. Hepatitis C, stigma and cure.

World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:6703-9. Crossref

14. Viral Hepatitis Control Office, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Hong Kong Viral Hepatitis Action

Plan 2020-2024. Available from: https://www.hepatitis.gov.hk/english/document_cabinet/action_plan.html. Accessed 4 Dec 2020.

15. Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Population and Household Statistics Analysed

by District Council District. Available from: https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B11303012019AN19B0100.pdf. Accessed 14 Jan 2021.

16. Leung CM, Wong WH, Chan KH, et al. Public awareness of

hepatitis B infection: a population-based telephone survey

in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2010;16:463-9.

17. Eni AO, Soluade MG, Oshamika OO, Efekemo OP,

Igwe TT, Onile-ere OA. Knowledge and awareness of

hepatitis B virus infection in Nigeria. Ann Glob Health

2019;85:56. Crossref

18. Tan CK, Goh GB, Youn J, Yu JC, Singh S. Public awareness

and knowledge of liver health and diseases in Singapore.

J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021 Mar 18. Epub ahead of

print. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jgh.15496. Accessed 2 May 2021. Crossref

19. Meireles LC, Marinho RT, Van Damme P. Three decades

of hepatitis B control with vaccination. World J Hepatol

2015;7:2127-32. Crossref

20. Posuwan N, Wanlapakorn N, Sintusek P, et al. Towards the

elimination of viral hepatitis in Thailand by the year 2030. J

Virus Erad 2020;6:100003. Crossref

21. Ha S, Timmerman K. Awareness and knowledge of

hepatitis C among health care providers and the public: a

scoping review. Can Commun Dis Rep 2018;44:157-65. Crossref

22. Wait S, Kell E, Hamid S, et al. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C in

southeast and southern Asia: challenges for governments.

Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;1:248-55. Crossref

23. Lee H, Fawcett J, Kim D, Yang JH. Correlates of hepatitis B

virus-related stigmatization experienced by Asians:

a scoping review of literature. Asia-Pac J Oncol Nurs

2016;3:324-34. Crossref

24. Smith-Palmer J, Cerri K, Sbarigia U, et al. Impact of stigma

on people living with chronic hepatitis B. Patient Relat

Outcome Meas 2020;11:95-107. Crossref

25. Huang J, Guan ML, Balch J, et al. Survey of hepatitis B

knowledge and stigma among chronically infected patients

and uninfected persons in Beijing, China. Liver Int

2016;36:1595-603. Crossref

26. Northrop JM. A dirty little secret: stigma, shame and

hepatitis C in the health setting. Med Humanit 2017;43:218-24. Crossref

27. Choi GH, Jang ES, Kim JW, Jeong SH. A survey of the

knowledge of and testing rate for hepatitis C in the general

population in South Korea. Gut Liver 2020;14:808-16. Crossref

28. Gautier RL, Wallace J, Richmond JA, Pitts M. The personal

and social impact of chronic hepatitis B: a qualitative

study of Vietnamese and Chinese participants in Australia.

Health Soc Care Community. 2020. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/hsc.13197.

Accessed 27 Jan 2021. Crossref

29. Haga SB, Barry WT, Mills R, et al. Public knowledge of and

attitudes toward genetics and genetic testing. Genet Test

Mol Biomarkers 2013;17:327-35. Crossref

30. Hui PW, Ng C, Cheung KW, Lai CL. Acceptance of

antiviral treatment and enhanced service model for

pregnant patients carrying hepatitis B. Hong Kong Med J

2020;26:318-22. Crossref

31. Cheung KW, Seto MT, Wong SF. Towards complete

eradication of hepatitis B infection from perinatal

transmission: review of the mechanisms of in utero

infection and the use of antiviral treatment during

pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2013;169:17-23. Crossref