© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF

MEDICAL SCIENCES

Electroconvulsive therapy machine

HK Cheung, FRCPsych (UK), Hon FHKCPsych

Guest author, Education and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a psychiatric

treatment in which seizure is electrically induced

in patients, typically with muscular convulsions

subdued by muscle relaxant and anaesthesia. This

ECT machine was generously donated to the Hong

Kong Museum of Medical Sciences by Dr John

Chung, son of the late Dr Cho-man Chung (Fig).

The ECT machine is an Ectonus Mark 3 model

manufactured by Ectron Ltd.

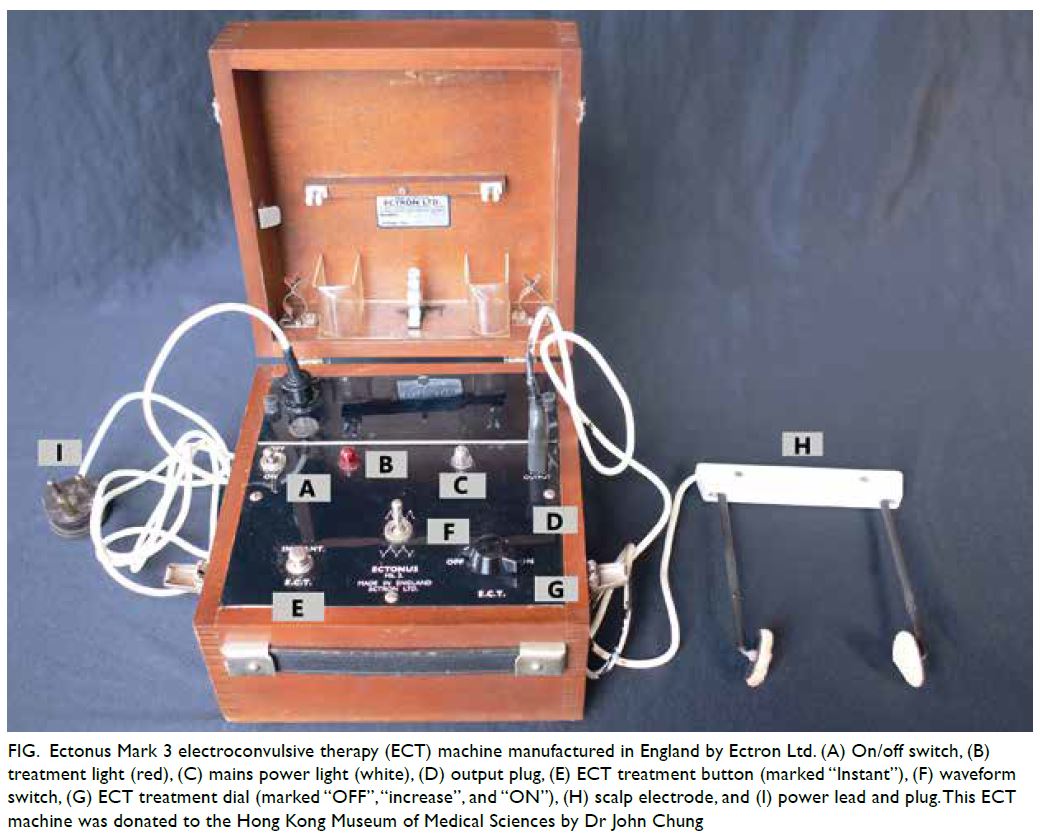

Figure. Ectonus Mark 3 electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) machine manufactured in England by Ectron Ltd. (A) On/off switch, (B) treatment light (red), (C) mains power light (white), (D) output plug, (E) ECT treatment button (marked “Instant”), (F) waveform switch, (G) ECT treatment dial (marked “OFF”, “increase”, and “ON”), (H) scalp electrode, and (I) power lead and plug. This ECT machine was donated to the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences by Dr John Chung

Convulsive therapy was first introduced in

1934 by Ladislas Joseph Meduna, a Hungarian

neuropsychiatrist who believed that schizophrenia

and epilepsy were antagonistic disorders. He induced

seizures first with camphor and then metrazol. In

1938, Ugo Cerletti, an Italian neuropsychiatrist and

his assistant Lucio Bini developed the idea of using

electricity as a substitute for metrazol in convulsive

therapy.1 Soon, ECT replaced metrazol therapy

worldwide, and Cerletti and his assistant Lucio Bini were nominated for a Nobel Prize. Later, the two

Italian inventors had a disagreement over the patent

of the ECT device, damaging their relationship.

Since the original Cerletti–Bini ECT apparatus,

there have been continuous modifications and

refinements in the ECT machines. All modifications

have had the same goal of maximising therapeutic

effect while minimising adverse consequences

(mainly confusion and amnesia). Many parameters

have been considered, including waveform, pulse

width, resistance (constant voltage or constant

current), electric charge, electrodes (unilateral

or bilateral), and dose (titration or fixed). In

addition, modern machines have added capabilities

to monitor physiological parameters such as

electroencephalogram, electrocardiogram, blood

oxygen level, and motion, as well as software that can

provide the clinician with detailed monitoring and

feedback.

In the 1940s, ECT was given in “unmodified”

form—without muscle relaxants—resulting in a fullscale

convulsive seizure, and sometimes inflicting

injury to the patient, including (rarely) fracture or

dislocation of the long bones. In order to modify

the convulsions, psychiatrists began to experiment

with curare, a poison from South America.

Unmodified ECT was introduced to Hong Kong in

the 1940s. Known colloquially as “straight ECT”,

it was performed by a psychiatrist without the use

of anaesthesia, muscle relaxant, or any machine-provided

physiological monitoring, and often

without proper informed consent from the patient.

In 1951, the introduction of suxamethonium

(succinylcholine), a safer synthetic alternative to

curare, led to the more widespread use of modified

ECT. Anaesthetics are unnecessary for ECT, as the

electric shock is capable of immediately rendering

the patient unconscious. Moreover, ECT can cause

retrograde amnesia, so the patient also has no

negative memory of the experience. Nevertheless,

muscle relaxants can invoke a feeling of suffocation,

so a short-acting anaesthetic was usually given in

addition to the muscle relaxant in order to spare the

patients this terrifying ordeal.

In the United States, ECT devices are

manufactured by two companies, Somatics and

MECTA. In the United Kingdom, the market for

ECT devices was long monopolised by Ectron Ltd.

In Hong Kong, following the British medical training

and tradition, Ectron machines were the only ones in

use for >50 years. It was not until the past 20 years

that non-British models were introduced into Hong

Kong.

The Ectonus Mark 3 ECT apparatus at the

Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences was one

of the first-generation models manufactured by

Ectron Ltd. The apparatus was housed in a square

wooden box with a lid that is hinged at the back, has

two clasps on the left and right sides near the front

and an attached leather handle on the front; the base

houses the motor of the apparatus and is covered

with a panel that with an on/off switch, an ECT

treatment button, a waveform switch, and an ECT

treatment dial, as well as various connectors and

indicator lights (Fig). At the time the apparatus was

manufactured and used, likely in the 1960s, current

would have been delivered in sine-wave form, with

a switch allowing the clinician to choose between

unidirectional or bidirectional sine waves. At that

time, it was believed that the unidirectional wave

produced fewer adverse effects but the bidirectional wave was more effective. A fixed dose of electricity

predetermined by the manufacturer could be

delivered by pressing a separate treatment button

(labelled “instant”). Alternatively, the operator

could choose to deliver a dose of variable strength

and/or duration by using the treatment dial. No

physiological monitoring or other software was

provided by the machine.

Despite improvements in technique and

equipment, the use of ECT declined from the 1950s

owing to declining public acceptance influenced

by negative depictions of ECT in the mass media,

as well as the emergence of alternative treatments.

Modern psychopharmacotherapy, including

effective antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood

stabilisers, tranquillisers, rendered ECT unnecessary

in most cases. There are also less-invasive cerebral

modulation interventions, such as repetitive

transcranial magnetic stimulation, which, although

not as effective as ECT, is acceptable to doctor

and patient because it does not require general

anaesthesia nor the induction of a seizure.

In Hong Kong, until the late 1970s, all ECT

procedures (including the general anaesthesia)

were carried out by psychiatrists. Typically, two

psychiatrists worked as a team, treating tens of

patients daily, with multiple ECT procedures each

hour. After this, anaesthetists participated in the

treatment. By the 2000s, taking the figures of Castle

Peak Hospital as an illustration, ECT was performed

in only two sessions per week, with one psychiatrist

and one anaesthetist. Typically only one or two

patients were treated per session, with no patients at

all in some sessions.

A modern course of ECT usually consists

of four to 12 treatments delivered 2 to 3 times per

week. Neuroimaging studies in people who have had

ECT, investigating differences between responders

and non-responders, find that responders have

decreased blood flow and metabolism in the frontal

lobes, and increased perfusion and metabolism in the

medial temporal lobe (such as the hippocampus).2

The general physical risks (and mortality) of ECT

are similar to those of a brief general anaesthesia.

The most common adverse effects are confusion

and transient memory loss. It is safe in pregnancy.

Despite the decline in use, ECT remains an

important backup treatment for patients with major

depressive disorder and other mental disorders,

including mania, catatonia, and treatment-resistant

schizophrenia, in whom other therapies have proved

ineffective.

References

1. Cerletti U. Electroshock therapy. In: Marti-Ibanez F, Sackler AM, Sackler MD, Sackler RR, editors. The Great

Physiodynamic Therapies in Psychiatry: an Historical Reappraisal. New York: Hoeber-Harper; 1956: 91-120.

2. Abbott CC, Gallegos P, Rediske N, Lemke NT, Quinn DK. A review of longitudinal electroconvulsive therapy:

neuroimaging investigations. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2014;27:33-46. Crossref