© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Lessons learnt from a genetic disease registry in

Hong Kong

Stephen TS Lam, MD, FHKAM (Paediatrics)1 CH To, PhD2; KW Leung, FCOphth HK, FRCOphth2; SP Yip, PhD3; Ivan FM Lo, FHKCPaed, FHKAM (Paediatrics)4; KP Tsang5

1 Department of Clinical Genetics Service, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong

2 School of Optometry, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong

3 Department of Health Technology and Informatics, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong

4 Clinical Genetic Service, Department of Health, Hong Kong

5 Retina Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Stephen TS Lam (taksumlam@gmail.com)

Purpose of a genetic disease registry

A registry for a specific clinical condition

serves multiple purposes. Firstly, it provides a

systemic index of patients and families with the

condition. Secondly, it helps in the classification

and management of patients with the condition.

Thirdly, it is a good resource for research into the

epidemiology, phenotype and genotype variations,

disease mechanisms, and treatment modalities of

the condition. Fourthly, from the above functions,

it works as a tool for advocacy for the welfare of

patients with the condition. To serve these purposes

for patients with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) in Hong

Kong, a registry was started, and the following is a

summary of the issues encountered and lessons learnt.

Retinitis pigmentosa registry in

Hong Kong

A rare genetic eye disorder, RP causes progressive

visual loss due to degeneration of cells in the

retina, estimated to affect 1 in 4000 people in the

United States and worldwide.1 There are, however,

no reported prevalence data in Hong Kong. The

diagnosis of RP is based on the clinical features

which include symptoms of night vision impairment

and tunnel vision, and the findings of typical retinal

appearance of attenuated blood vessels, so-called

bone spicule pigmentation or its variant appearance

and an atrophic optic disc. These are supported

by an abnormal constricted visual field and a nonrecordable

or abnormal electroretinography with

diminished a and b waves with increased implicit

time. The RP is also highly genetically heterogeneous,

with more than 80 genes implicated and their mode

of inheritance varies. This means one patient’s

RP may be a different genetic disorder from that

of another RP patient, with different inheritance,

natural course, and prognosis. The rarity of the

disease and the associated genetic heterogeneity are major obstacles to facilitating research and

enhancing medical care to these patients and their

families. The Hong Kong Retinitis Pigmentosa

Society was started in 1995 as a patient group, and

subsequently renamed as Retina Hong Kong. Under

the auspices of Retina Hong Kong, a Scientific

and Medical Advisory Committee (SMAC) was

established. In 1997, the SMAC secured a grant from

the Healthcare and Promotion Fund of the Hong

Kong Government to start organising the Hong

Kong Patients Registry of Retinal Degenerations. It

was the original intention for this registry to cover

most retinal degenerative conditions. However,

because of resource constraints, it was decided that

the scope should be limited to RP as the first group of

members to be covered. Hence, the registry was also

abbreviated as the Hong Kong Retinitis Pigmentosa

Registry. It turned out to be the first registry of its

kind among Chinese populations in the whole world,

and to the best of our knowledge, there is no other

Chinese Registry presently.

The objectives of the Retinitis Pigmentosa

Registry are three-fold, including:

To provide detailed ophthalmic and genetic

examinations for inherited retinal degenerative

diseases patients so as to ascertain the symptoms

and the genetic pattern of the patients.

To collect relevant data and build up a database

for the benefit of future scientific, medical, and

sociological researches.

To provide lifelong follow-up services for patients

who participate in the project and to notify and

refer them for appropriate treatment as soon as it

is available.

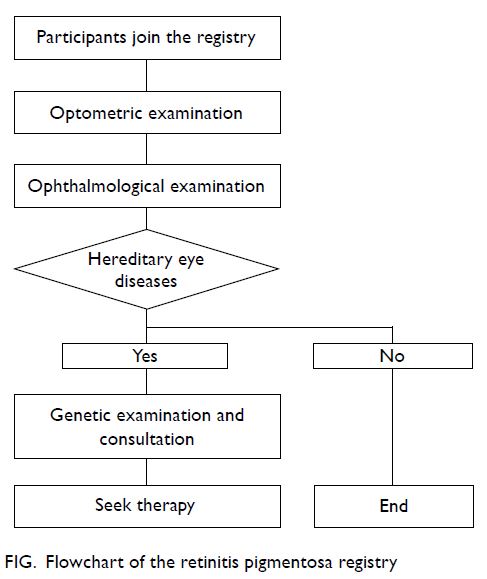

The holder of the Registry is the Retina Hong

Kong, whose members were offered the option

of voluntary participation in the Registry. Patient

members were invited to be seen by the specialists in

the SMAC in a sequence as outlined in the flowchart

in the Figure for clinical examinations, diagnostic

testing, and counselling.

Right at the start of their participation,

members were advised of the detailed flow of the

whole process. More importantly, they were advised

of their rights in this participation before signing for

consent. Their rights included:

To obtain detailed ophthalmic examination and

eye care apart from advice on genetics.

To know well their condition and progress

through different clinical examinations.

To be informed of all findings that might help in

their treatment plan.

To make use of relevant information to formulate

their future plan on career and family.

The Registry is maintained strictly in accordance

with the Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance.

Participants may obtain all information relating

to their own case, which is stored in the database of the

Registry.

To ensure that participants are well informed

of the flow of the registry and their rights and

obligations, pamphlets were designed and made

available as part of the informed consent process.

The first clinical assessment for the

participants was an optometric evaluation at The

Hong Kong Polytechnic University (HKPU), where

refraction studies, ocular health assessment, visual

field test, electroretinogram studies, and fundus

photography were performed. This was followed by

an ophthalmologic examination with dilated fundus

evaluation. As shown in the Figure, eye diseases are

defined upon clinical criteria as to whether they

fall into the categories of known hereditary nature. The third clinical assessment was genetic evaluation

and counselling together with sample collection

(blood sample with DNA extraction) performed at

the Clinical Genetic Service of the Department of

Health. Further genetic testing was carried out at

the molecular laboratory of HKPU for mutational

analysis. Periodic clinical and molecular conferences

were conducted among members of the SMAC to

confirm the exact clinical diagnosis, genetic defects,

and inheritance patterns for individual participants

to guide further genetic counselling, whence other

family members were also invited to participate on a

voluntary basis.

Periodic assessment of the Registry was

conducted by the SMAC and reported to the Retina

Hong Kong. The first of these reports covered the

period 1999 to 2005, during which a total of 94

families were documented. After detailed evaluation

was conducted conjointly by the specialists in the

SMAC, the diagnosis of RP was documented in

72 of these families with inheritance pattern

classified as simplex (44, 61.1%), autosomal dominant

(12, 16.7%), autosomal recessive (12, 16.7%) and

X-linked recessive (4, 5.6%), which showed

comparable results to those published by other

centres2 3; and the remaining 22 families of alternative

diagnosis with various genetic backgrounds. It

was noted that the phenotype of patients with

non-RP retinal degenerations may overlap with

that of RP, leading to erroneous clinical diagnosis,

as exemplified in 30% of this cohort. By combining

clinical data and genetic analysis, a more definitive

diagnosis could be achieved.

Cases of RP and other retinal degenerative

diseases were categorised and published.4 5 In these

early days of molecular analysis, genetic studies were

carried out on putative genes individually, hence on

a gene by gene basis, instead of on a multiplex basis.

As expected, the positive yield of such a laborious

approach was necessarily low.

Funding issues

It was most fortunate that the Healthcare Promotion

Fund has sponsored this registry for nearly 5 years

(1997-2002). With the cessation of this sponsorship,

the Registry could not be sustained, and was

suspended in 2002. It was resumed in April 2003

after further sponsorship was obtained from Retina

Hong Kong, with additional financial input from the

individual institutes to which the members of SMAC

were affiliated.

Further progress of the registry

With the advent of the massively parallel sequencing

(also known as next generation sequencing)

technology, it became possible for mutational

analysis to be performed on a multiplex instead of single gene basis. The previous cohort examined

until 2002 was expanded with new entries to a total

of 116 families by 2012. Their samples were subjected

to next generating sequencing performed on MiSeq

(Illumina) system, initially at HKPU, and, as an

ongoing process, also in Clinical Genetic Service

of the Department of Health. Additional mutations

were identified and put to good use in genetic

counselling of the affected individuals and families.

Lessons learnt

The above narration has highlighted some issues

pertaining to the success or failure of this kind

of registries. The Retinitis Pigmentosa Registry

is notably the first of its kind among all Chinese

populations, and hence has set an exemplary

function for others. The unique feature of the

Retinitis Pigmentosa Registry is that it is initiated

and led by a patient organisation, which works for

the welfare of its members. As such, the interest

of the patients and their families were considered

the primary objective of the registry. All necessary

steps were taken to upkeep the ethical principles

for patient confidentiality and informed consent

as exercised in the design and implementation of

this registry. In addition, a central core of highly

motivated individuals and institutes from the

clinical and scientific community is needed to

provide the academic and service input to make it

viable. From this combined clinical and scientific

approach, an accurate and reliable diagnosis

could be provided for genetic counselling of many

subjects. The data attained from the studies had also

provided information for the spectrum of retinal

degenerations seen in Chinese populations.

Yet, this registry has also uncovered a

major problem with setting up genetic registries:

financial instability. The experience shown here

is that a strategy is needed to ensure the financial

sustainability of the project. To achieve the objectives

of the provision of ongoing care for the participants,

a secure source of funding is needed on a long-term basis. It is advisable to explore different sources of

financial commitment both in the public and private

sectors.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis or

interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical

revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/support

The funders mentioned in the article had no role in study design, data collection/analysis/interpretation or manuscript

preparation.

References

1. National Eye Institute. Retinitis pigmentosa. Available

from: https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/retinitis-pigmentosa. Accessed 1 Jan 2021.

2. Ferrari S, Di Iorio E, Barbaro V, Ponzin D, Sorrentino FS,

Parmeggiani F. Retinitis pigmentosa: genes and disease

mechanisms. Curr Genomics 2011;12:238-49. Crossref

3. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences:

Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. About

GARD. Available from: http://rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Accessed 1 Jan 2021.

4. Yip SP, Cheung TS, Chu MY, et al. Novel truncating

mutations of the CHM gene in Chinese patients with

choroideremia. Mol Vis 2007;13:2183-93.

5. Lim KP, Yip SP, Cheung SC, Leung KW, Lam ST, To CH.

Novel PRPF31 and PRPH2 mutations and co-occurrence

of PRPF31 and RHO mutations in Chinese patients with

retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol 2009;127:784-90. Crossref