© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Ketamine-associated nephropathy treated with

renal transplantation: a case report

John SL Leung, MB, BS1; Vincent YK Poon, FRCSEd (Urol)1; Thomas YC Lam, FRCSEd (Urol)1; CK Chan, FRCSEd (Urol)1; Y Chiu, FRCSEd (Urol)1; TY Chu, FRCSEd (Urol)1; Samuel KS Fung, FRCP (Edin), FRCP (Irel)2; WK Ma, FRCSEd (Urol)1

1 Department of Surgery, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr WK Ma (drmawk@gmail.com)

Case report

We present a 37-year-old man who had been on

continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis for 8 years

owing to ketamine-associated end-stage renal failure.

He received a cadaveric renal graft in December

2019 at Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong.

He first presented with haematuria and dysuria

in 2004. He had been abusing ketamine steadily for 4

years. Mid-stream urine culture and acid-fast bacillus

culture were negative; urine cytology, renal function,

and ultrasonography of the urinary system were

unremarkable. The patient subsequently defaulted

on investigations and follow-up appointments.

The patient returned in 2010 with more

severe symptoms of ketamine cystitis and reflux

nephropathy. At that time, he was taking 0.3 to 0.6 g

of ketamine by nasal inhalation up to 10 times a day.

He had urinary frequency every 10 minutes and

creatinine was 283 μmol/L (estimated glomerular

filtration rate [eGFR] 25 mL/min/1.73 m2). Flexible

cystoscopy showed cystitis changes; a biopsy of the

urothelium yielded neutrophilic exudates mixed with

fibrin, and fibroblastic stromal reaction. Ultrasound

scan revealed bilateral hydronephrosis and a

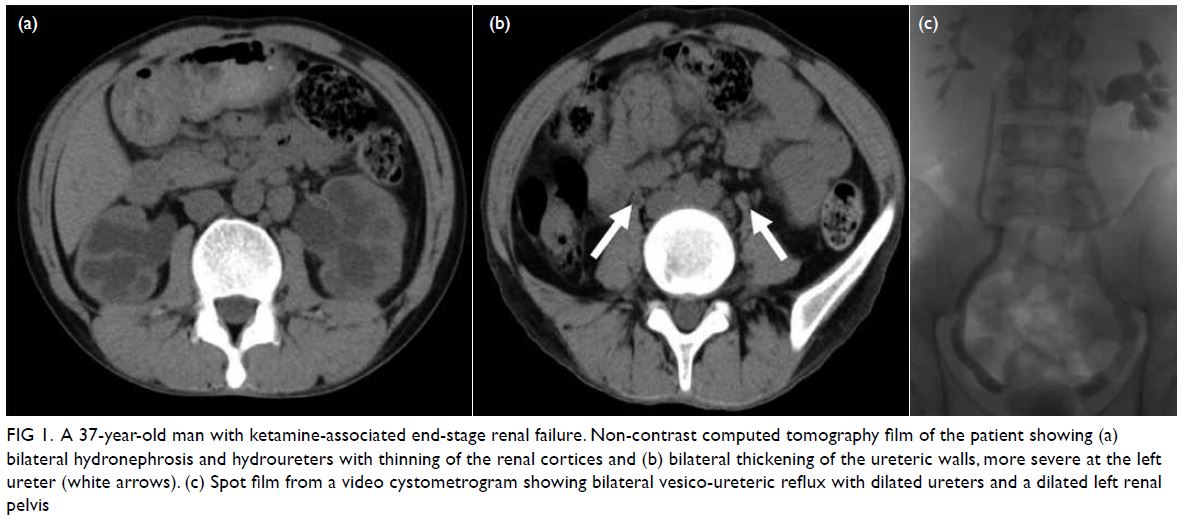

thickened bladder wall. Non-contrast computed tomography showed thinning of the renal cortex

and bilateral hydronephrosis as well as thickening

of the ureters, all indicative of ureteric inflammation

(Fig 1). Repeat urine cytology, routine culture, and

acid-fast bacillus cultures were all negative.

Figure 1. A 37-year-old man with ketamine-associated end-stage renal failure. Non-contrast computed tomography film of the patient showing (a) bilateral hydronephrosis and hydroureters with thinning of the renal cortices and (b) bilateral thickening of the ureteric walls, more severe at the left ureter (white arrows). (c) Spot film from a video cystometrogram showing bilateral vesico-ureteric reflux with dilated ureters and a dilated left renal pelvis

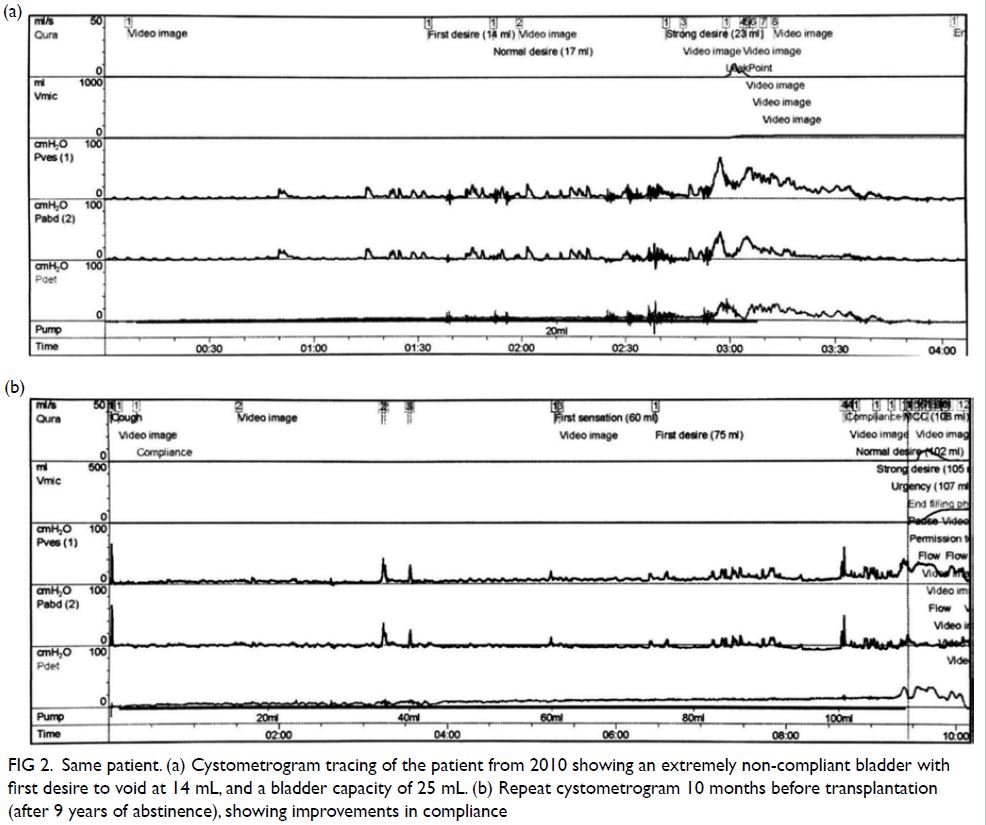

Video cystometrogram demonstrated typical

features of ketamine cystitis, namely that of a small

and contracted bladder: the bladder capacity was

25 mL; first desire to void was at 14 mL; detrusor

instability occurred at a Pdet of 22 cmH2O (Fig 2).

Additionally, bilateral grade III vesico-ureteric reflux

was documented (Fig 1). The patient agreed only to

a urethral catheter and refused upper tract urinary

diversion with percutaneous nephrostomies.

Figure 2. Same patient. (a) Cystometrogram tracing of the patient from 2010 showing an extremely non-compliant bladder with first desire to void at 14 mL, and a bladder capacity of 25 mL. (b) Repeat cystometrogram 10 months before transplantation (after 9 years of abstinence), showing improvements in compliance

He began abstaining from ketamine in 2010

but refused dialysis until 2011 when his creatinine

had reached 1079 μmol/L (eGFR 5 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Annual broad-spectrum drug screening of the

patient’s urine samples was negative for ketamine

and its metabolites since then.

A repeat video cystometrogram in 2013, 3 years after complete abstinence from ketamine, showed

improvements from his first video cystometrogram

in 2010. Bladder capacity had improved to 124 mL;

first desire to void improved to 51 mL. Detrusor overactivity was noted at 120 mL when the Pdet was 30 cmH2O. Only a left grade I vesico-ureteric reflux

was observed.

In 2019, another video cystometrogram

showed improvement in the first desire to void to

75 mL, no detrusor overactivity, and smooth

bladder contour with no vesico-ureteric reflux

(Fig 2). Bladder functional capacity was 200 mL.

It was therefore deemed worthwhile for him to

undergo renal transplantation without augmentation

cystoplasty.

The patient received a cadaveric renal graft

from a 14-year-old donor. The operation was

uneventful and he was no longer dialysis-dependent.

At 8 weeks after transplantation, his creatinine level

was 124 μmol/L (eGFR 63 mL/min/1.73 m2), and

urine output about 2000 mL per day. At 12 weeks

after the transplantation, his creatinine level was

122 μmol/L (eGFR 65 mL/min/1.73 m2), and urine

output remained stable at about 2000 mL per day.

Daytime frequency ranged from once every 1

to 3 hours, with 100 to 300 mL of urine per void.

At 22 weeks after transplantation his creatinine

level was 117 μmol/L (eGFR 68 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Ultrasonography excluded graft kidney

hydronephrosis and hydroureter.

Discussion

This is the first reported case of ketamine-associated nephropathy successfully treated with renal

transplantation.

Ketamine cystitis was first reported in Hong

Kong by Chu et al1 in 2007. Since then, numerous

publications regarding its management have

emerged. Abstinence remains the cornerstone

of treatment as it results not only in improved

cystitis symptoms, but also bladder capacity and

compliance.2 3 Early upper tract protection is

paramount in patients with ketamine cystitis. Up to

16.8% of chronic ketamine abusers have unilateral or

bilateral hydronephrosis owing to ureteric strictures

or vesico-ureteric reflux.4 Strategies to protect the

upper tract include percutaneous nephrostomy

or long-term urethral catheterisation to keep the

bladder decompressed.5 Internal ureteric stents

may aggravate cystitis symptoms and hence may

not be tolerated.6 In our case, the patient refused

percutaneous nephrostomies for upper tract

protection, and missed the window of opportunity

to preserve his renal function before development of

end-stage renal failure and need for dialysis.

There are two important prerequisites for renal transplantation in ketamine-related end-stage

renal failure. The first is abstinence to ensure

that the graft kidney and ureter are not subject to

ketamine toxicity. Significant improvements in

bladder compliance and capacity may be achieved

only after at least 1 year of abstinence.1 3 7 Since

improvement may take several years to stabilise,

we suggest that consideration for transplantation

should be at least 1 year after stabilisation of bladder

function improvement and proven by serial negative

urine toxicology screening. The second prerequisite

is that bladder compliance and capacity are sufficient

to accommodate the volume of urine produced by

the graft kidney. A well-functioning graft kidney

with a poorly compliant bladder can be damaged by

vesico-ureteric reflux. Serial urodynamic studies to

document improvements in bladder capacity before

considering renal transplantation are mandatory.

Although there is no absolute cut-off value for

satisfactory bladder volume before transplantation,

persistent vesico-ureteric reflux that does not

resolve or downgrade with ketamine abstinence

would be an indication for augmentation cystoplasty

prior to transplantation. This will avoid debilitating

urinary frequency after transplantation or early graft

failure due to vesico-ureteric reflux. In our patient,

bladder compliance and capacity improved steadily

with prolonged abstinence, as documented by serial

cystometrograms. Renal transplantation without

augmentation cystoplasty was therefore an option.

Patients with unsatisfactory bladder compliance

and capacity should be counselled for augmentation

cystoplasty before undergoing transplantation. This

concept can be likened to the use of augmentation

cystoplasty prior to renal transplantation in patients

with high-pressure neurogenic bladder.8 Nonetheless

augmentation cystoplasty for patients with ketamine

cystitis is technically challenging owing to the fibrotic

bladder with transmural thickening. Furthermore,

the need for clean intermittent self-catheterisation

afterwards may be cumbersome for this young

patient group, especially if substantial ketamine-related

bladder pain remains.

Frequent follow-up after transplantation to

monitor renal function, functional bladder capacity

in the form of a bladder diary, and ultrasonography to

exclude graft hydronephrosis should be maintained.

A video cystometrogram to exclude vesico-ureteric

reflux is mandatory should graft function deteriorate.

Early and sustained abstinence as well as

advocation for early upper tract urinary diversion

are important factors in the prevention of ketamine-related

nephropathy. Clinicians should maintain

a low threshold of suspicion for ketamine abuse in

young patients who present with recurrent lower

urinary tract symptoms.9 A population-based survey

of lower urinary tract symptoms in Hong Kong

adolescents revealed that of those who reported lower urinary tract symptoms, 6.6% were substance abusers.10

Management of the symptoms of ketamine

cystitis should adopt a stepwise approach starting with

abstinence and analgesics; failing that, intravesical

instillation of hyaluronic acid, hydrodistension, and

eventually augmentation cystoplasty.3

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design of the study, acquisition of the data, analysis or interpretation of the

data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors

had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved

the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/support

This case report received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of

Helsinki and provided informed consent for the treatment/

procedures and consent for publication.

References

1. Chu PS, Kwok SC, Lam KM, et al. ‘Street ketamine’–associated bladder dysfunction: a report of ten cases. Hong

Kong Med J 2007;13:311-3.

2. Cheung RY, Chan SS, Lee JH, Pang AW, Choy KW,

Chung TK. Urinary symptoms and impaired quality of life

in female ketamine users: persistence after cessation of use.

Hong Kong Med J 2011;17:267-73.

3. Hong YL, Yee CH, Tam YH, Wong JH, Lai PT, Ng CF. Management of complications of ketamine abuse: 10 years’

experience in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2018;24:175-81. Crossref

4. Yee CH, Teoh JY, Lai PT, et al. The risk of upper urinary

tract involvement in patients with ketamine-associated

uropathy. Int Neurourol J 2017;21:128-32. Crossref

5. Chu P, Ma WK, Wong S, et al. The destruction of the lower urinary tract by ketamine abuse: a new syndrome? BJU Int

2008;102:1616-22. Crossref

6. Tsai YC, Kuo HC. Ketamine cystitis: Its urological impact and management. Urol Sci 2015;26:153-7. Crossref

7. Yee CH, Lai PT, Lee WM, Tam YH, Ng CF. Clinical outcome of a prospective case series of patients with

ketamine cystitis who underwent standardized treatment

protocol. Urology 2015;86:236-43. Crossref

8. Basiri A, Otookesh H, Hosseini R, Moghaddam SM. Kidney transplantation before or after augmentation cystoplasty in

children with high-pressure neurogenic bladder. BJU Int

2009;103:86-8. Crossref

9. Ng SH, Tse ML, Ng HW, Lau FL. Emergency department presentation of ketamine abusers in Hong Kong: a review

of 233 cases. Hong Kong Med J 2010;16:6-11.

10. Tam YH, Ng CF, Wong YS, et al. Population-based survey

of the prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in

adolescents with and without psychotropic substance

abuse. Hong Kong Med J 2016;22:454-63. Crossref