Hong Kong Med J 2021 Apr;27(2):154–6 | Epub 9 Apr 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Optimising vitamin D levels in patients with COVID-19

Jasndeep Kaler, BA1; Azhar Hussain, BA, MBA1,2; Dua Azim, MB, BS3; Syed Ali, BS4; Sundus Nasim, MB, BS3

1 Xavier University School of Medicine, Oranjestad, Aruba

2 Doctoral Candidate of HealthCare Administration, Franklin University, Ohio, United States

3 Dow Medical College, Dow University of Health Sciences, Karachi, Pakistan

4 Stony Brook University, New York, United States

Corresponding author: Mr Azhar Hussain (azharhu786@gmail.com)

As the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) continues, the focus

on establishing a comprehensive treatment strategy

is greater than ever. Coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) places an immense burden on public

health and limited hospital capacity; thus, it comes

as no surprise that an effective therapeutic option

has become a dire necessity. Although many drugs

are currently undergoing clinical trials to test

their efficacy and safety for treating patients with

COVID-19, no specific medicine has been confirmed

as truly beneficial to date.

The pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 is considered

a two-phase viral response: the first immune

defence-mediated protective phase and the second

inflammation-driven destructive phase. Clinicians

need immune boosters to manage phase one of

COVID-19, and immune suppressors to manage

phase two.

Recently, tocilizumab, an immunosuppressive

drug, has gained considerable attention as a

potential treatment option for patients with

COVID-19. Tocilizumab, a synthetic monoclonal

antibody, competitively inhibits the binding of

interleukin (IL)-6 to its receptor, making it incapable

of inducing immune damage, and relieving the

inflammatory reactions.1 Therefore, tocilizumab

provides hope for treating critically ill patients with

COVID-19; however, it can be used to manage only

phase two, the inflammatory phase of COVID-19.

Moreover, tocilizumab is expensive and requires

intravenous administration, and it is associated with

complications including gastrointestinal perforation

and elevated pancreatic biomarkers.1 Thus, there

is a growing need for a cheaper and more readily

available alternative treatment that can be used in

both phases of COVID-19.

Several studies have demonstrated a potential

link between vitamin D and various respiratory

illnesses.2 The role of vitamin D against viral infections

is twofold. First, vitamin D induces the production

of antiviral peptides such as cathelicidin in the

respiratory epithelium, which strengthens mucosal defenses.3 Second, vitamin D reduces cytokine

production by enhancing the innate immune system

and suppressing the overactivation of the adaptive

immune system secondary to viral load.4 Recent

evidence also suggests an association of increased

levels of IL-6 with vitamin D deficiency in HIV

infection.5 Vitamin D may mitigate the production of

pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines,

such as tumour necrosis factor α and IL-6, generated

by the innate immune system in response to

SARS-CoV-2 infection.

There is little evidence on the role of vitamin D

deficiency in COVID-19 severity and mortality. The

SARS-CoV-2 outbreak emerged during winter in the

Northern Hemisphere; influenza virus also happens

to peak in winter.6 Because supplementation with

vitamin D lowers the risk of influenza A,7 insufficient

levels of vitamin D due to reduced sunlight exposure

in Northern regions may have contributed to the

increased incidence of COVID-19.

Another indirect connection between poorer

outcomes of COVID-19 and low vitamin D levels

arises from the observation that some ethnicities are

differentially affected by ongoing pandemic. Darker

skin tone raises the risk of vitamin D deficiency, and

estimates from the Office for National Statistics,

United Kingdom, indicate a fourfold risk of

COVID-19-related deaths in dark-skinned

individuals from England and Wales relative to

lighter-skinned individuals.8

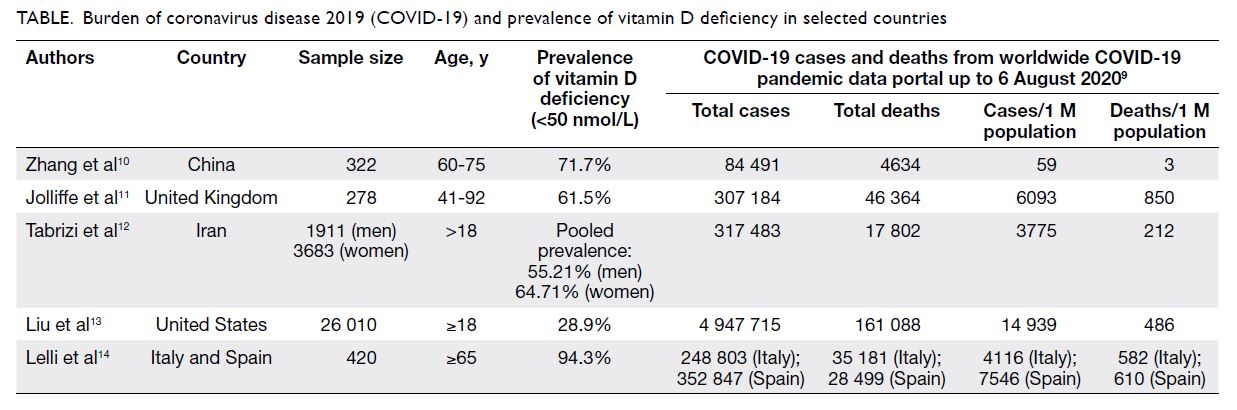

We extracted data on the number of

COVID-19 cases and deaths up to 6 August 2020

from the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic database9

and data on about the prevalence of vitamin D

deficiency from previous studies (Table).10 11 12 13 14 We

found that people residing in regions that are

severely affected by COVID-19 also often had

vitamin D deficiency, further reinforcing the

potential correlation of vitamin D with seriousness

of the disease.

Table. Burden of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in selected countries

Although low vitamin D levels are implicated

in severity and mortality of COVID-19, there is

no evidence to date supporting supplementation with vitamin D as a therapy with dose-response

curve. However, several randomised open-label

and blinded clinical trials are currently in progress

of investigating vitamin D as a treatment option for

COVID-19, rather than a preventive measure.15 16 17

Considering the expensiveness, limited

availability, and adverse effects of tocilizumab, we

believe that vitamin D is safe and offers a viable

therapeutic option. The twofold mechanism of

vitamin D in countering SARS-CoV-2 infection

reinforces our confidence in its preventive and

therapeutic adequacy. Further research is required

to elucidate the exact mechanism of vitamin D in

SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. We recommend that

patients with COVID-19 have blood vitamin D

levels tested on hospitalisation; these data would

be invaluable in investigating any links between

COVID-19 mortality and vitamin D. In the

meantime, we recommend following the vitamin D

supplementation guidelines set out by public health

authorities.

Author contributions

J Kaler and A Hussain contributed to the study concept and

critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual

content. All authors contributed to acquisition and analysis

of the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors had full

access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final

version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy

and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This commentary received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Nasim S, Hashmi SH, Azim D, Kumar S, Nasim J. Tocilizumab for COVID-19: a real ‘miracle drug’? Infect

Dis (Lond) 2020;52:681-2. Crossref

2. Berry DJ, Hesketh K, Power C, Hyppönen E. Vitamin D

status has a linear association with seasonal infections and

lung function in British adults. Br J Nutr 2011;106:1433-40. Crossref

3. Gombart AF, Borregaard N, Koeffler HP. Human

cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene is a

direct target of the vitamin D receptor and is strongly up-regulated

in myeloid cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3.

FASEB J 2005;19:1067-77. Crossref

4. Greiller C, Martineau A. Modulation of the immune response to respiratory viruses by vitamin D. Nutrients

2015;7:4240-70. Crossref

5. Manion M, Hullsiek KH, Wilson EM, et al. Vitamin D

deficiency is associated with IL-6 levels and monocyte

activation in HIV-infected persons. PLoS One

2017;12:e0175517. Crossref

6. Hope-Simpson RE. The role of season in the epidemiology of influenza. J Hyg (Lond) 1981;86:35-47. Crossref

7. Urashima M, Segawa T, Okazaki M, Kurihara M, Wada Y,

Ida H. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to

prevent seasonal influenza A in schoolchildren. Am J Clin

Nutr 2010;91:1255-60. Crossref

8. Office for National Statistics, UK Government. Coronavirus

(COVID-19) related deaths by ethnic group, England and

Wales: 2 March 2020 to 10 April 2020. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/coronavirusrelateddeathsbyethnicgroupenglandandwales/2march2020to10april2020. Accessed 5 Jul 2020.

9. Worldometer. COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.Accessed 6 Aug 2020.

10. Zhang W, Zheng X, Wang Y, Xiao H. Vitamin D deficiency as a potential marker of benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Urology 2016;97:212-8. Crossref

11. Jolliffe DA, James WY, Hooper RL, et al. Prevalence,

determinants and clinical correlates of vitamin D deficiency

in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

in London, UK. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2018;175:138-45.Crossref

12. Tabrizi R, Moosazadeh M, Akbari M, et al. High prevalence

of vitamin D deficiency among Iranian population: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Med Sci 2018;43:125-39.

13. Liu X, Baylin A, Levy PD. Vitamin D deficiency and

insufficiency among US adults: Prevalence, predictors and

clinical implications. Br J Nutr 2018;119:928-36. Crossref

14. Lelli D, Pérez Bazan LM, Calle Egusquiza A, et al. 25(OH)

vitamin D and functional outcomes in older adults admitted

to rehabilitation units: the safari study. Osteoporos Int

2019;30:887-95. Crossref

15. ClinicalTrials.gov, US National Library of Medicine.

Improving vitamin D status in the management of

COVID-19. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04385940. Accessed 6 Aug 2020.

16. ClinicalTrials.gov, US National Library of Medicine.

Prevention and treatment with calcifediol of COVID-19

coronavirus-induced acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04366908. Accessed 6 Aug 2020.

17. ClinicalTrials.gov, US National Library of

Medicine. Preventive and therapeutic effects of oral

25-hydroxyvitamin D3 on coronavirus (COVID-19) in

adults. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04386850. Accessed 6 Aug 2020.