Hong Kong Med J 2021 Feb;27(1):61–3 | Epub 2 Feb 2021

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Successfully conducting an objective structured

clinical examination with real patients during the

COVID-19 pandemic

CH Lee#, MB, BS; Pauline Y Ng#, MB, BS; Shirley YY Pang#, MD; David CL Lam, MD; CS Lau, MD

Department of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

# These authors contributed equally to this commentary.

Corresponding author: Prof CS Lau (cslau@hku.hk)

Introduction

For decades, the objective structured clinical

examination (OSCE) has been regarded as a valid

and reliable method of assessing clinical competency

in medical education. The choice of patient

representation in an OSCE depends on context

and availability.1 The coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) pandemic presents an unprecedented

challenge to both medical education and examinations

worldwide, especially high-stakes qualification

examinations such as the final-year medical student

OSCE. Whereas some medical schools elected to

cancel all clinical examinations and grant provisional

registration to graduates, others have resorted to

the use of manikins, video recordings, or simulated

patients for assessment of clinical skills.2 Hong Kong

was one of the earliest regions in the world to be

affected by COVID-19.3 Owing to uncertainty about

the scale of the local outbreak, the Department of

Medicine at The University of Hong Kong decided to

uphold the format of its final-year OSCE by involving

assessment of real patients in all clinical stations. We

hereby report the organisation details of our OSCE

conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a

focus on adaptations that were necessary to address

concerns about infection control, whilst maintaining

the overall validity of the examination.

Objective structured clinical

examination design and structure

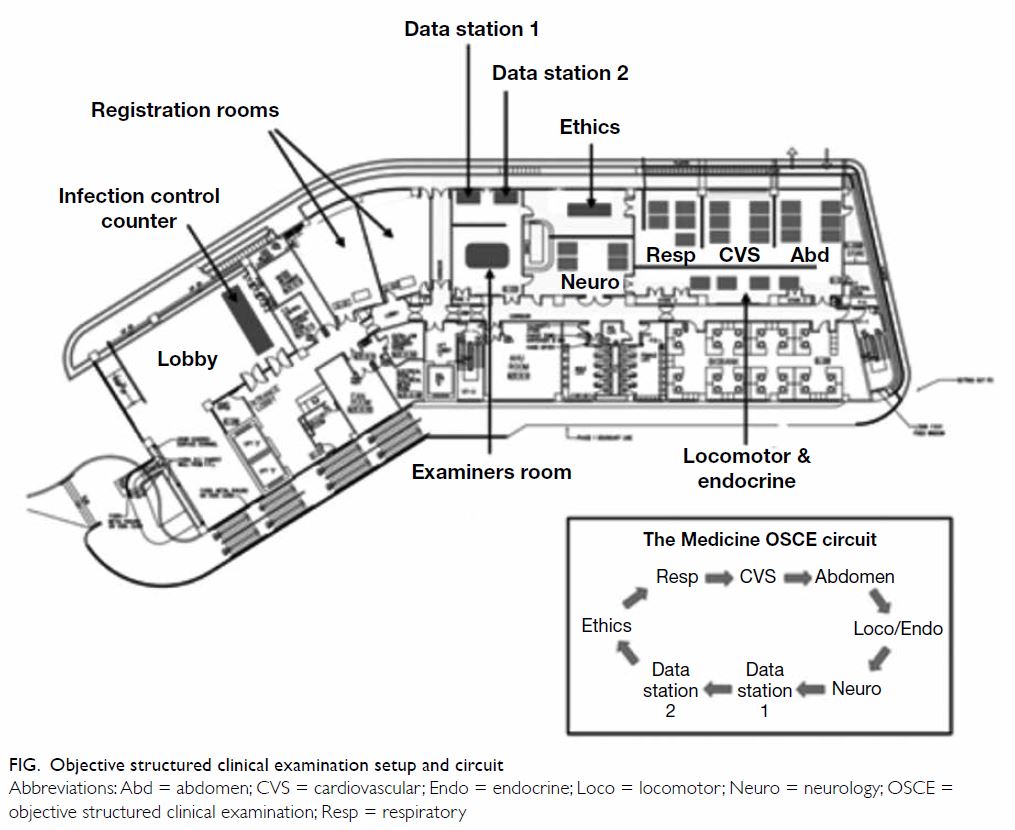

Our OSCE for the graduating class of 2020 was

conducted from 4 to 8 May 2020. A total of 204

candidates, divided into 26 cohorts, were examined.

As in previous years, each candidate was examined

in a circuit of eight stations within 80 minutes,

consisting of five clinical stations with real patients,

two data interpretation stations, and one on ethics

and communication with a trained actor. Candidates

were examined at each clinical station by a pair of

physician examiners, who separately graded their

performance based on a standardised marking

scheme, with emphasis on the approach to patients,

core examination skills, and ability to detect and

interpret physical signs.

In the past, our medical OSCE had always

been conducted in the ward areas of Queen Mary

Hospital, Hong Kong. However, following our first

confirmed COVID-19 patient on 22 January 2020

and activation of the Emergency Response Level

in public hospitals 3 days later mandating that

all teaching activities conducted within hospital

compounds be suspended,4 our OSCE had to be

relocated to a non-clinical area on campus. Seminar

rooms had to be temporarily converted to patient

cubicles using portable ward screens, and a total of

five seminar rooms were employed to construct the

OSCE circuit (Fig).

Altogether, 52 volunteer patients from the

community were recruited, with an average of

24 patients participating on each day of the

examination due to multiple attendances. Since

most clinical staff were deployed to combat

COVID-19, a crew of 70 research assistants,

laboratory technicians, post-doctoral fellows

and administrative staff, who mostly had no

prior experience with the OSCE, was enlisted as

administrators and helpers.

Infection control measures

Our OSCE was also conducted when the Prohibition

on Group Gathering Regulation, which limited

group gatherings of more than four people in

public places, was in force. Our Faculty successfully

acquired exemption from this Regulation for our

OSCE. Since close physical contact was inevitable

during clinical examination and in order to safeguard

all participants, several faculty-wide stringent

precautionary infection control measures were

implemented.

Firstly, all participants, including candidates,

examiners, patients and helpers, submitted a deep

throat saliva specimen for severe acute respiratory

syndrome coronavirus 2 reverse-transcription

polymerase chain reaction test at least 2 days prior to

their OSCE participation. Secondly, all participants

were required to submit a health declaration form

1 day prior to each day of examination. Those who

declared any suggestive symptom in the past 7 days,5 history of travel or contact with confirmed or

suspected COVID-19 patients in the past 14 days,

were flagged for further considerations before being

allowed to participate in the examination on the

following day. Thirdly, participants who persistently

had a body temperature of ≥37.5°C measured on

arrival at the examination venue were subjected to

clinical assessment by the on-duty infection control

supervisor to determine if they would be permitted

to participate. Protocols were in place for clinical

assessment of candidates for these purposes.

At all times during the OSCE, participants

were required to wear surgical masks, and examiners

and candidates had been instructed not to unmask

a patient at any time. Demonstration of cough

manoeuvre was also not mandatory. To minimise

close contact, fundoscopic examination was

replaced by interpretation of retinal photos in the

data stations. Participants were required to perform

strict hand hygiene using alcohol-based hand rub

and disinfect their clinical instruments before and

after examining each patient. Social distancing

was observed in all waiting areas, with a spacing of 2-metre radius between seats. All bedsheets,

pillows, and pyjamas of patients were changed daily,

and the examination hall was disinfected twice daily.

Lunch and drinks were all individually packaged

and consumed within each individual’s assigned

station.

At the conclusion of our OSCE, only one

candidate did not attend the examination because

of persistent fatigue and will be allowed to sit in the

Supplementary Examination. No candidates were

denied entry on the day of examination. A total

of 53 clinical teachers assessed the candidates at

the clinical examination stations. All volunteering

patients had negative COVID-19 tests and there

were at least three patients in each clinical station

daily. No major equipment failure occurred during

OSCE, except for a slight delay in the electronic

scoring system on the first day of the examination,

which were immediately resolved by our on-site

computer technicians. The candidates’ pass and fail

rates were similar to previous OSCEs. Importantly,

no participants have contracted COVID-19 through

participation in the examination.

Difficulties and limitations

The implementation of the above measures was not

without difficulties, and there remain limitations

worth highlighting. Although an out-of-hospital

venue was reassuring to patients who wished to avoid

hospital attendance during the pandemic, this limited

the diversity of patients, especially in terms of their

disease severity, represented in our OSCE. Some

patients who had participated in OSCEs in past years

declined to help this time for fear of contracting the

virus despite the out-of-hospital venue. Nonetheless,

since the selection of patients was based on a list

of core and optional medical competencies that

students are expected to acquire during various

clerkship teachings in our Department, the overall

disease spectrum represented was still comparable

with OSCEs in previous years.

Moreover, with compulsory quarantine

imposed on all inbound travellers entering Hong

Kong, special arrangements had to be made with

our external examiner, who was based in the United

Kingdom. A list of the patients recruited for OSCE

was sent to the external examiner to evaluate diversity

and appropriateness of cases, and the distinction

viva was conducted over video-teleconferencing

with his presence.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected all

strata of the healthcare system, and medical schools

are no exception. Organising an in-person real-patient

OSCE was an immense, but not impossible

challenge. We demonstrated that strict infection

control measures and detailed planning, albeit with a

high administrative cost, could provide reassurance

to all OSCE participants, facilitate the smooth

running of the examination, and uphold the standard

we expect from our medical graduates. Lastly,

we should emphasise that good patient rapport

fostered by physicians during routine clinical care is

unarguably a major key to the successful conduction

of our OSCE where our patients have demonstrated

tremendous support and trust in the measures

we have taken. While it remains uncertain when

this pandemic would come to an end, or if social

distancing practices have to be kept indefinitely, our successful experience may provide some guidance

and encouragement to those who are pressing on to

deliver safe and valid qualifying examinations during

one of the most difficult times in this century.

Author contributions

Concept or design: CH Lee, CS Lau, PY Ng, SYY Pang.

Drafting of the manuscript: CH Lee, PY Ng, SYY Pang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: DCL Lam, CS Lau.

Drafting of the manuscript: CH Lee, PY Ng, SYY Pang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: DCL Lam, CS Lau.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

CS Lau is Immediate Past President of the Hong Kong

Academy of Medicine. Other co-authors report no conflicts

of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank the Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine for its enduring

support. We are grateful for the efforts and contributions

from all participants, especially our patients, who have made

this objective structured clinical examination possible and

successful.

References

1. Collins JP, Harden RM. AMEE Medical Education Guide

No. 13: real patients, simulated patients and simulators in

clinical examinations. Med Teach 1998;20:508-21. Crossref

2. Boursicot K, Kemp S, Ong TH, et al. Conducting a high-stakes OSCE in a COVID-19 environment. MedEdPublish

2020;9:54.Crossref

3. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government. Latest situation of cases

of COVID-19. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/local_situation_covid19_en.pdf. Accessed 18 May

2020.

4. Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government. Hospital

Authority activates Emergency Response Level. Available

from: https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/pad/200125Eng6.pdf. Accessed 25 Jan 2020.

5. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China.

Lancet 2020;395:497-506. Crossref