Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE CME

2020 Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists guideline on investigations of premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding

Jacqueline HS Lee, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; Edith OL Cheng, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)2; KM Choi, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)3; SF Ngu, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)4; Rachel YK Cheung, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1,5 for the Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

5 Chairman, HKCOG Guideline Sub-committee

Corresponding author: Dr Rachel YK Cheung (rachelcheung@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal

women is a common gynaecological symptom and

composes of abnormality in the frequency, duration,

regularity, and flow volume of menstruation. It could

constitute the presentation of various gynaecological

malignancies. An appropriate history and physical

examination are mandatory to ascertain the diagnosis.

Depending on the clinical condition, a complete

blood picture, thyroid function test, clotting profile,

chlamydia test, cervical smear, and pregnancy test

can be performed. Ultrasound should be performed

in cases with a pelvic mass, unsatisfactory physical

examination, persistent symptoms, or no response

to medical treatment. In women aged ≥40 years,

an out-patient endometrial biopsy with Pipelle

should be performed. In women aged <40 years

with risk factors for endometrial cancer, persistent

symptoms, or no response to medical treatment, an

endometrial biopsy should be performed to rule out

endometrial cancer. Hysteroscopy or saline infusion sonohysterography is more sensitive than ultrasound

for diagnosing endometrial pathology. Details of the

above recommendations are presented.

Introduction

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is a common

problem in gynaecological practice and represents a

major proportion of out-patient attendance. A postal

survey in the United Kingdom found that AUB and

its subgroup, heavy menstrual bleeding, affected

15% to 25% of women aged 18 to 54 years.1 In Hong

Kong, the prevalence of AUB is not available, but

the following reference provides some information.

According to the 2014 Hong Kong College of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Territory Wide

Audit, the numbers of hospital admissions with

the diagnoses of ‘menorrhagia’ and ‘dysfunctional

uterine bleeding’ were 4080 and 3806, respectively.2

There were 6455 diagnostic hysteroscopies and

3075 hysteroscopic procedures conducted.2 Of all

operative hysteroscopic procedures performed,

the numbers of polypectomies and myomectomies

were 2468 (80%) and 380 (12%), respectively.2

Although many patients with AUB might not require

admission, the case volume mentioned in the above

report may reflect the scope of the problem locally.

As patterns of investigation became diversified, a guideline on AUB was considered

necessary. Premenopausal women are targeted by

this guideline. Postmenopausal bleeding is caused by

a different disease spectrum and is not included in

this guideline.

Definitions and initial

investigations of abnormal uterine

bleeding

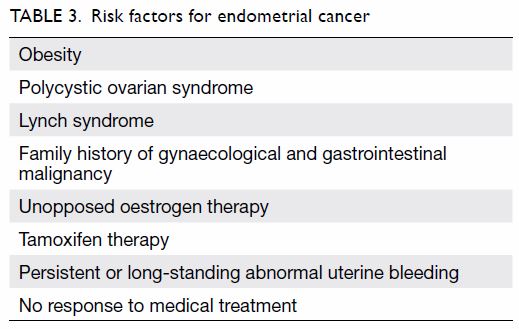

The International Federation of Gynecology and

Obstetrics classifies AUB in the reproductive

years into chronic versus acute non-gestational

AUB.3 Chronic non-gestational AUB is defined as

bleeding from the uterine corpus that is abnormal

in frequency, duration, regularity, and/or volume

(Table 1) and has been present for the majority of

the preceding 6 months. Acute AUB is defined as

an episode of heavy bleeding that, in the clinician’s

opinion, is of sufficient quantity to require immediate

intervention to minimise or prevent further blood

loss. Menorrhagia is heavy cyclical menstrual blood

loss over several consecutive cycles without any intermenstrual or postcoital bleeding (ie, without

cycle disturbance). The National Institute for Health

and Care Excellence (NICE) defines heavy menstrual

bleeding as excessive menstrual loss that interferes

with a woman’s physical, social, emotional, and/or

material quality of life.4 Intermenstrual bleeding,

premenstrual and postmenstrual spotting, and

perimenopausal bleeding can be considered as

dysfunctional uterine bleeding after exclusion of

organic causes.

Table 1. Abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

Obtaining an accurate menstrual history is

mandatory to guide the clinician’s diagnosis and

understand the impact on a woman’s quality of life

(online supplementary Appendix 1). On general

examination, any pallor or thyroid gland enlargement

should be noted. If there are features suggestive of

thyroid dysfunction or coagulopathy from history

or physical examination, a thyroid function test or

coagulopathy screening can be ordered accordingly.

History suggestive of coagulopathy includes heavy

menstrual bleeding since menarche, a family history

of coagulopathy, easy bruising, bleeding of the gums,

and epistaxis. However, routine thyroid function tests

or coagulopathy screening are not recommended

in all patients with menorrhagia. Speculum or

bimanual examination could elucidate the causes for

abnormal bleeding, such as cervical polyps, cervical

carcinoma, uterine fibroids, adenomyosis, or ovarian

tumours (online supplementary Appendix 1). The

following investigations can be arranged depending

on the clinical situation: (1) complete blood count to

look for anaemia; (2) pregnancy test; (3) ultrasound

scan, especially if physical examination suggests a

pelvic mass; (4) endometrial assessment; (5) cervical

smear if due; and (6) chlamydia screening in cases of

postcoital or intermenstrual bleeding.

Endometrial assessment

There are five main methods of endometrial

assessment: ultrasound scanning, magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI), endometrial biopsy or

aspirate, hysteroscopy, and dilatation and curettage

(D&C) under various modes of anaesthesia.

Ultrasound scanning

Ultrasound scanning, particularly the transvaginal

route, is used to assess endometrial thickness,

endometrial and myometrial consistency, and

abnormalities of the endometrial lining (eg,

submucosal fibroids or polyps). However, most

studies have investigated the endometrial thickness

of postmenopausal women. Smith-Bindman et al5

observed that the average endometrial thicknesses

were 4 mm, 10 mm, 14 mm, and 20 mm in normal

postmenopausal women, those with endometrial

polyps, those with endometrial hyperplasia, and

those with endometrial carcinoma, respectively. However, the prediction of endometrial pathology

based on ultrasound results in premenopausal

women was not reliable because of the great overlap

between the normal range and that of women with

endometrial pathology.

The NICE guideline4 recommends that in

patients with examination suggestive of fibroids,

a pelvic ultrasound should be performed.

Depending on the size of the uterus, transvaginal

or transabdominal ultrasonography could be

performed. Transvaginal ultrasonography produces

better image quality because of its higher frequency,

which allows greater image resolution at the expense

of decreased depth of penetration. In patients

in whom physical examination is impossible or

unsatisfactory, or symptoms persist despite medical

treatment, an ultrasound should also be arranged.

Pelvic ultrasound can be useful for detecting gross

endometrial or myometrial pathology such as fibroids

and adenomyosis. However, pelvic ultrasonography

does not replace an endometrial biopsy.

In cases where vaginal access is difficult or impossible, such as in adolescents and virgin girls,

transrectal ultrasonography should be offered. This

technique has been shown to provide better image

quality compared with the transabdominal route

without causing significant discomfort to patients.6

Saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS)

involves the instillation of 5 to 15 mL of normal

saline into the uterine cavity and may allow better

detection of endometrial polyps and submucosal

fibroids. A 2017 meta-analysis concluded that two-dimensional

SIS is highly sensitive for detection of

endometrial polyps and submucosal uterine fibroids,

with pooled sensitivity values of 93% and 94% and

specificity of 81% and 81%, respectively.7 Clinicians

may consider SIS in cases where further evaluation

of endometrial lesions is required.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging has been shown to

be more sensitive than transvaginal ultrasound

(TVS) for the identification of fibroids, especially

the growth of submucosal fibroids into the uterine

cavity.8 Magnetic resonance imaging is slightly more

sensitive than TVS for diagnosing adenomyosis

(sensitivity: 77% vs 72%).9 10 However, the chance of

identifying important additional findings by MRI

over ultrasound has to be weighed against the waiting

time and cost of MRI. Magnetic resonance imaging

should not be the routine for all cases of AUB. In

cases where vaginal access is difficult or impossible,

or when it is difficult to differentiate between fibroids

and adenomyosis, there is a role for MRI.

Endometrial biopsy

The main purpose of obtaining an endometrial

biopsy or endometrial aspirate is to exclude

endometrial pathology like hyperplasia, disordered

endometrium, or malignancies. Most endometrial

biopsies can be performed in out-patient or office

clinics and have the advantages of being simple,

quick, safe, and convenient and avoiding the

need for anaesthesia. Furthermore, the device is

disposable, and the procedure is much less costly

than conventional D&C.

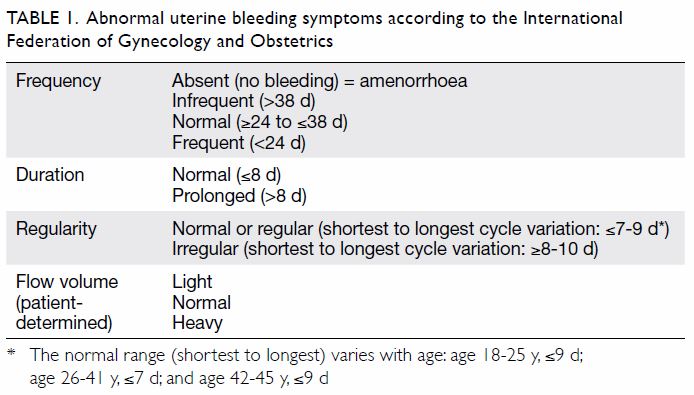

The Pipelle is the most common out-patient

endometrial assessment device used in the United

Kingdom and Hong Kong (Fig). Other devices

includes Novak (a silastic cannula with a beveled

lateral opening), Tis-u-Trap (a plastic curette with

suction), the Vabra aspirator (a cannula connected

to a vacuum pump), Endorette (a plastic cannula

with multiple openings), Tao Brush (a sheath brush

device), Cytospat (a polypropylene cannula with a

rhomboid head), Accurette (a quadrilateral-shaped

curette with four cutting edges), Explora (a plastic

curette with a Randall-type cutting edge), and

Z-sampler (a flexible polypropylene device). A meta-analysis

including 60 articles found that Pipelle

performs as well as D&C and as well as or better

than other endometrial sampling devices in terms of

sampling adequacy and sensitivity. Pipelle seems to

be better than the other options in terms of pain/discomfort and costs.11 The sample adequacy rate

was consistently high for Pipelle, mostly >85%,

compared with 98% for D&C.11 Pipelle’s specimen

adequacy rate and concordance rate to histology

on hysterectomy were similar to those of D&C.

Pipelle biopsy is reliable for excluding endometrial

carcinoma: previous studies showed that Pipelle

detected 98% of endometrial carcinomas.12

The Vabra device can sample a larger

proportion of the endometrium (42%) compared

with Pipelle (4%).13 However, other studies did not

find a better specimen adequacy rate of the Vabra

device over Pipelle14 15 (Table 2 11 12 16 17 18).

Table 2. Sensitivity and specificity of endometrial sampling devices for detecting endometrial carcinoma

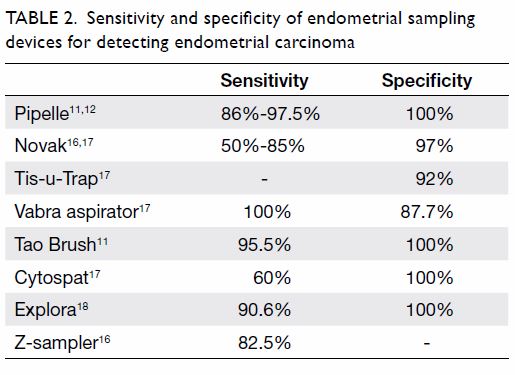

Endometrial cancer is thought to be uncommon

in women aged <40 years, and this matches the

reported local experience.19 In 2017, the Hong Kong

Cancer Registry report showed that out of a total of

1076 new cases of cancer of the endometrial corpus,

only 47 cases (4.4%) occurred in women aged

<40 years.19 Although endometrial cancer is

uncommon in women aged <40 years, its incidence

is increasing. In 2017, the age-specific incidences for

endometrial carcinoma in various age-groups were

4, 9, 18, 66, and 64 per 100 000 women at ages 30, 35,

40, 50, and 55 years, respectively, with the incidence

peaking at ages 50 to 54 years.19 In 2007, the figures

were 2 and 6 per 100 000 women at ages 30 and 35,

respectively.

At what age should the gynaecologist perform endometrial biopsy? It had been suggested that

routine endometrial biopsy is not necessary for

AUB in women aged <40 years. However, in view

of the increasing incidence of endometrial cancers

among younger women, an endometrial assessment

is warranted for women aged <40 years who present

with AUB and also have other high-risk features

(Table 3). Instead of arbitrarily choosing an age at

which endometrial biopsy should or should not be

done, the woman’s risk of endometrial carcinoma

should be assessed. When they present with AUB,

women at high risk of endometrial cancer need

endometrial biopsy regardless of age. Therefore, Hong

Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

recommends endometrial biopsy in all women

with AUB aged ≥40 years and in women with risk

factors for endometrial carcinoma irrespective of

age. Patients with persistent symptoms or in whom

medical treatments have failed should also undergo

endometrial biopsy.

Hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy allows direct visualisation of the

whole endometrial cavity, lower segment, and

cervical canal. Hysteroscopy can detect small

polyps or submucosal fibroids and provide an

opportunity for endometrial biopsy without the

need for general anaesthesia. The NICE guideline

recommends out-patient hysteroscopy for

women with uterine cavity abnormalities or when

endometrial pathology is suspected because it is

more accurate than pelvic ultrasound.4 A Hong

Kong study showed that out-patient hysteroscopy

was successful in 92% of patients.20 Prospective

studies have shown that diagnostic hysteroscopy

had significantly better diagnostic performance

than SIS and TVS.16 The sensitivity and specificity

for any uterine abnormality of SIS and TVS were

92% and 89% versus 60% and 56%, respectively.

The sensitivity and specificity for diagnostic

hysteroscopy were 97% and 92%, respectively.21

The patients’ acceptability was high, and the failure rate was low, with failure mainly occurring due to

pain during the procedure, distorted uterine cavity,

and tight cervical os, especially in postmenopausal

and nulliparous patients. The last problem can be

partially overcome by using a hysteroscope of smaller

diameter (minihysteroscopy). A ‘no touch’ approach

with vaginoscopy has been shown to be quicker,

less painful, and more successful than standard

hysteroscopy and can be considered for out-patient

hysteroscopy.22

A randomised controlled trial23 comparing

TVS, out-patient hysteroscopy, and endometrial

biopsy with in-patient hysteroscopy and D&C showed

that a combination of transvaginal scan, Pipelle

endometrial biopsy, and out-patient hysteroscopy

had similar efficacy to in-patient hysteroscopy and

D&C for the investigation of AUB. Transvaginal scan

and endometrial biopsy can therefore be considered

as the first-line investigation, followed by out-patient

hysteroscopy.24

Some authors have suggested that a normal

cavity on hysteroscopy obviates the need for an

endometrial biopsy. However, normal hysteroscopy

findings are not conclusive of the absence of

premalignant or malignant lesions and do not

eliminate the need for endometrial sampling, as they

do not substitute for benign histological examination

findings.25

Dilatation and curettage

Dilatation and curettage, and the endometrial

histology obtained by that method, were previously

considered as the ‘gold standard’ in AUB

management. However, multiple studies showed that

D&C is not superior to endometrial assessment with

Pipelle or other out-patient endometrial assessment

devices, and D&C requires general anaesthesia.11

Dilation and curettage only should no longer be

the gold standard in endometrial pathological

assessment, but D&C with concurrent hysteroscopy

may be useful when intrauterine lesions are

suspected, as it allows direct visual assessment of

the endometrial cavity. For patients in whom out-patient

hysteroscopy or endometrial biopsy is not

possible, in-patient hysteroscopy and D&C under

general anaesthesia should be offered, but D&C

does not have therapeutic value in AUB except for

temporarily stopping heavy menstrual bleeding.

Summary of recommendations

1. The chance of endometrial carcinoma in women

aged <40 years is low. However, endometrial

assessment is warranted if there are risk factors

for endometrial carcinoma, if symptoms are

persistent/long-standing, or symptoms fail to

respond to medical treatment (Grade B).

2. Pelvic ultrasound (preferably TVS) and endometrial sampling with Pipelle are the preferred first-line methods of assessing AUB. Hysteroscopy is indicated if uterine cavity abnormalities are suspected (Grade B).

3. Out-patient hysteroscopy is safe and reliable and should be the preferred setting for diagnostic hysteroscopy (Grade A).

4. Routine first-line D&C should be discouraged. Dilation and curettage should be reserved for women requiring general anaesthesia for other indications (Grade A).

2. Pelvic ultrasound (preferably TVS) and endometrial sampling with Pipelle are the preferred first-line methods of assessing AUB. Hysteroscopy is indicated if uterine cavity abnormalities are suspected (Grade B).

3. Out-patient hysteroscopy is safe and reliable and should be the preferred setting for diagnostic hysteroscopy (Grade A).

4. Routine first-line D&C should be discouraged. Dilation and curettage should be reserved for women requiring general anaesthesia for other indications (Grade A).

A summary of the recommendations are

shown in the online supplementary Appendix 2.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: JHS Lee, EOL Cheng, KM Choi, SF Ngu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: JHS Lee, EOL Cheng, KM Choi, SF Ngu.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: JHS Lee, EOL Cheng, KM Choi, SF Ngu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: JHS Lee, EOL Cheng, KM Choi, SF Ngu.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

This guideline was produced by the Hong Kong College of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists as an educational aid and

reference for obstetricians and gynaecologists practising in

Hong Kong. The guideline does not define a standard of care,

nor is it intended to dictate an exclusive course of management.

It presents recognised clinical methods and techniques for

consideration by practitioners for incorporation into their

practice. It is acknowledged that clinical management may

vary and must always be responsive to the needs of individual

patients, resources, and limitations unique to the institution

or type of practice. Particular attention is drawn to areas

of clinical uncertainty in which further research may be

indicated.

Declaration

The content of this guideline has been published in the

Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Guidelines Number 5, revised July 2020 (http://www.hkcog.org.hk/hkcog/Download/Guideline_on_investigations_of_premenopausal_women_with_abnormal_uterine_bleeding.pdf). This is a revised version of the 2001 Hong Kong College of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists guideline on investigations

of premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding

(http://www.hkcog.org.hk/hkcog/Download/Abnormal%20uterine%20bleeding_2001.pdf).

Funding/support

This medical practice paper received no specific grant from

any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit

sectors.

References

1. Shapley M, Jordan K, Croft PR. An epidemiological survey

of symptoms of menstrual loss in the community. Br J Gen

Pract 2004;54:359-63.

2. Hong Kong College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists.

Territory-wide audit in obstetrics & gynaecology.

2014. Available from: http://www.hkcog.org.hk/hkcog/Download/Territory-wide_Audit_in_Obstetrics_Gynaecology_2014.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2020.

3. Munro MG, Critchley HO, Fraser IS, FIGO Menstrual

Disorders Committee. The two FIGO systems for normal

and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification

of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive

years: 2018 revisions. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2018;143:393-408. Crossref

4. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heavy

menstrual bleeding: assessment and management NICE

guideline [NG88]. 2018. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88. Accessed 25 Feb 2020.

5. Smith-Bindman R, Kerlikowska K, Feldstein V, et al.

Endovaginal ultrasound to exclude endometrial cancer and

other endometrial abnormalities. JAMA 1998;280:1510-7. Crossref

6. Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Rebarber A, Goldstein SR,

Tsymbal T. Transrectal scanning: an alternative when

transvaginal scanning is not feasible. Ultrasound Obstet

Gynecol 2003;21:473-9. Crossref

7. Bittencourt CA, Dos Santos Simões R, Bernardo WM,

et al. Accuracy of saline contrast sonohysterography

in detection of endometrial polyps and submucosal

leiomyomas in women of reproductive age with abnormal

uterine bleeding: systematic review and meta-analysis.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017;50:32-9. Crossref

8. Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, Ledertoug S, Olesen F.

Evaluation of the uterine cavity with magnetic resonance

imaging, transvaginal sonography, hysterosonographic

examination, and diagnostic hysteroscopy. Fertil Steril

2001;76:350-7. Crossref

9. Bazot M, Daraï E. Role of transvaginal sonography and

magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of uterine

adenomyosis. Fertil Steril 2018;109:389-97. Crossref

10. Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, Balogun M, Khan KS.

Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the

diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing

test accuracy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2010;89:1374-84. Crossref

11. Narice BF, Delaney B, Dickson JM. Endometrial sampling

in low-risk patients with abnormal uterine bleeding: a

systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Fam Pract

2018 30;19:135. Crossref

12. Stovall G, Photopulos GJ, Poston WM, Ling FW, Sandles LG.

Pipelle endometrial sampling in patients with known

endometrial carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol 1991;77:954-6.

13. Rodriguez GC, Yaqub N, King ME. A comparison of

the Pipelle device and Vabra aspirator as measured by

endometrial denudation in hysterectomy specimens:

the Pipelle samples significantly less of the endometrial

surface than the Vabra aspirator. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1993;168:55-9. Crossref

14. Eddowes HA, Read MD, Codling BW. Pipelle: a more

acceptable technique for outpatient endometrial biopsy. Br

J Obstet Gynaecol 1990;97:961-2. Crossref

15. Naim NM, Mahdy ZA, Ahmad S, Razi ZR. The Vabra

aspirator versus the Pipelle device for outpatient endometrial sampling. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol

2007;47:132-6. Crossref

16. Larson DM, Krawisz BR, Johnson KK, Broste SK.

Comparison of the Z-sampler and Novak endometrial

biopsy instruments for in-office diagnosis of endometrial

cancer. Gynecol Oncol 1994;54:64-7. Crossref

17. Antoni J, Folch E, Costa J, et al. Comparison of Cytospat

and Pipelle endometrial biopsy instruments. Eur J Obstet

Gynecol Reprod Biol 1997;72:57-61. Crossref

18. Kufahl J, Pedersen I, Sindberg Eriksen P, et al. Transvaginal

ultrasound, endometrial cytology sampled by Gynoscann

and histology obtained by Uterine Explora Curette

compared to the histology of the uterine specimen. A

prospective study in pre- and postmenopausal women

undergoing elective hysterectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol

Scand 1997;76:790-6. Crossref

19. Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital Authority, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Cancer incidence and mortality

report in Hong Kong. 2016-2017 Available from: www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg, Assessed 25 Feb 2020.

20. Lo KW, Yuen PM. The role of outpatient diagnostic

hysteroscopy in identifying anatomic pathology and

histopathology in the endometrial cavity. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2000;7:381-5. Crossref

21. Grimbizis GF, Tsolakidis D, Mikos T, et al. A prospective

comparison of transvaginal ultrasound, saline infusion

sonohysterography, and diagnostic hysteroscopy in

the evaluation of endometrial pathology. Fertil Steril

2010;94:2720-5. Crossref

22. Smith PP, Kolhe S, O’Connor S, Clark TJ. Vaginoscopy

against standard treatment: a randomised controlled trial.

BJOG 2019;126:891-9. Crossref

23. Tahir MM, Bigrigg MA, Browning JJ, Brookes ST, Smith PA.

A randomised controlled trial comparing transvaginal

ultrasound, outpatient hysteroscopy and endometrial

biopsy with inpatient hysteroscopy and curettage. Br J

Obstet Gynaecol 1999;106:1259-64. Crossref

24. Bain C, Parkin DE, Cooper KG. Is outpatient diagnostic

hysteroscopy more useful than endometrial biopsy

alone for the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding

in unselected premenopausal women? A randomised

comparison. BJOG 2002;109:805-11. Crossref

25. Bakour SH, Dwarakanath LS, Khan KS, Newton JR. The

diagnostic accuracy of outpatient miniature hysteroscopy

in predicting premalignant and malignant endometrial

lesions. Gynaecol Endosc 1999;8:143-8. Crossref