Hong

Kong Med J 2020 Dec;26(6):492–9 | Epub 16 Dec 2020

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Cross-border reproductive care use by women

with infertility in Hong Kong: cross-sectional

survey

Dorothy YT Ng, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1,2; Ellen MW Lui, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; SF Lai, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)3; Tracy SM Law, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)4; Grace CY Wong, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)5; Ernest HY Ng, MD, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)5

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong

4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong

5 The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Dorothy YT Ng (dor723@gmail.com)

Abstract

Objectives: Cross-border reproductive care (CBRC)

is an increasingly common global phenomenon, but

there is a lack of information regarding its frequency

among residents of Hong Kong. This study aimed to

evaluate the use of CBRC and the factors affecting its

use among residents of Hong Kong.

Methods: This cross-sectional questionnaire study

collected data from 1204 women with infertility who

attended Hong Kong Hospital Authority and Family

Planning Association infertility clinics.

Results: In total, 178 women (14.8% of all

respondents) had used CBRC. Among respondents

who had not used CBRC, 36.3% planned to use or

would consider it. The main factors influencing

the likelihood of using CBRC among women with

infertility in Hong Kong use were long waiting times

in the public sector and high cost in the private

sector. Taiwan was the most preferred destination

for CBRC (69.6% of respondents). Most information

concerning CBRC was accessed via the internet.

More than two thirds of respondents believed that

the government in Hong Kong should formulate

some regulations or guidance regarding CBRC.

Conclusion: Nearly one in six women with infertility in Hong Kong had used CBRC. Among women who had not used CBRC, more than one third planned

to use or would consider it. The main factors

influencing the likelihood of CBRC use were long

waiting times in the public sector and high cost in

the private sector. These results will help clinicians

to more effectively counsel patients considering

CBRC and facilitate infertility services planning by

authorities in Hong Kong.

New knowledge added by this study

- Nearly one in six women with infertility in Hong Kong has used cross-border reproductive care (CBRC). Among women who have not used CBRC, more than one third plan to use CBRC or would consider using CBRC.

- The main factors influencing the likelihood of using CBRC instead of local reproductive care included long waiting times in the public sector and high cost in the private sector.

- More than two thirds of respondents believe that the authorities in Hong Kong should formulate some regulations or guidance regarding CBRC.

- Clinicians should remind patients about the implications of the number of embryos transferred during CBRC and the potential risk of multiple pregnancy.

- The safety of women in Hong Kong who travel abroad for fertility treatment is jeopardised by the current lack of uniform clinical and safety regulations in other parts of the world.

- To ensure fair access to infertility care in Hong Kong, local health authorities should implement more effective measures to manage long waiting lists in the public sector.

Introduction

Cross-border reproductive care (CBRC) is an

increasingly popular global trend in reproductive

medicine, whereby patients travel out of their

home country to receive fertility treatment.1 2

This phenomenon has also been referred to as

“reproductive tourism”, “reproductive travel”, “health

travel”, and “reproductive exile”.3 4 Among these

terms, CBRC has a relatively neutral meaning and

is used in the present study to avoid stigmatisation. Thus far, CBRC has been described in Europe, North

America, Middle East, Australia, and Japan.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

A survey in Europe in 2010 showed that there

were 24 000 to 30 000 cycles of CBRC annually,

which involved 11 000 to 14 000 patients.12 13 Because

525 640 total treatment cycles were performed

during the same period, approximately 5% of the

fertility care was estimated to involve CBRC. In

the US, nearly 4% of all fertility treatment provided

was delivered to non-US residents; this comprised

approximately 6000 cycles.13 14 The reasons for

CBRC use in Europe12 included avoidance of legal

restrictions at home (eg, fertility treatment for single

and lesbian women in France and pre-implantation

genetic testing in Germany), avoidance of lengthy

waiting lists at home (eg, for egg donation in

the United Kingdom), lower treatment cost, and

treatment within a more favourable framework (eg,

gamete donation with donor anonymity).

The aim of the present study was to evaluate

the use of CBRC and its influencing factors in Hong

Kong.

Methods

Participants

Women with infertility who attended infertility

clinics in the Hospital Authority (ie, Queen Mary

Hospital, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital,

Kwong Wah Hospital, and Prince of Wales Hospital)

and the Family Planning Association (FPA) from

1 February 2017 to 31 March 2019 were recruited to participate in the study. Women who could not

read English or Chinese were excluded from the

study. All participants provided written informed

consent to participate. The study was approved by

the Institutional Review Boards of all participating

centres, including the Hong Kong East Cluster Ethics

Committee (HKECREC-2018-014); The University

of Hong Kong Hong Kong West Cluster Clinical

Research Ethics Committee (UW 18-266); Kowloon

Central/Kowloon East Cluster Clinical Research

Ethics Committee (KC/KE-18-0073/ER-4); North

Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics

Committee (NTEC-2018-0384); and the Ethics

Panel and the Health Services Subcommittee of the

FPAHK (OA1-2).

Questionnaire development and distribution

A search of the literature was conducted using

PubMed using the terms “cross border reproductive

care”, “reproductive travel”, “infertility”, and

“Hong Kong”. It revealed no existing validated

questionnaires concerning CBRC use in Hong Kong.

Most questions in our questionnaire were adapted

from another questionnaire focused on CBRC.5 The

questionnaire content focused on three main areas:

(1) demographic information, (2) reproductive

history and attitudes concerning fertility, and (3)

factors affecting the use of CBRC. The questionnaire

was evaluated and revised by specialists in Obstetrics

and Gynaecology and subspecialists in Reproductive

Medicine, all of whom worked in the Hospital

Authority. It was then piloted by administration to

five patients in the clinic with the aim of ensuring

that patients could understand the questionnaire.

Women with infertility who attended infertility

clinics in the Hospital Authority or FPA were invited

to participate in the study. The questionnaire was

distributed by clinic nurses to clinic attendees.

Participation was voluntary and patients were

invited to complete the questionnaire without

assistance while awaiting medical consultation. The

questionnaire required approximately 20 minutes to

complete. Completed questionnaires were returned

to the clinic nurse at the end of the consultation.

Statistical analysis

Calculations were performed using SPSS Statistics

for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk [NY],

US). Associations between attitudes towards CBRC

and background variables (total monthly household

income, education level, years of attempting

conception, and age) were explored using the Chi

squared test. P values <0.05 were considered to

indicate statistical significance. Logistic regression

was used to investigate whether respondent age,

education level, years of attempting conception, and

total monthly household income were associated

with CBRC use.

Results

Respondent characteristics

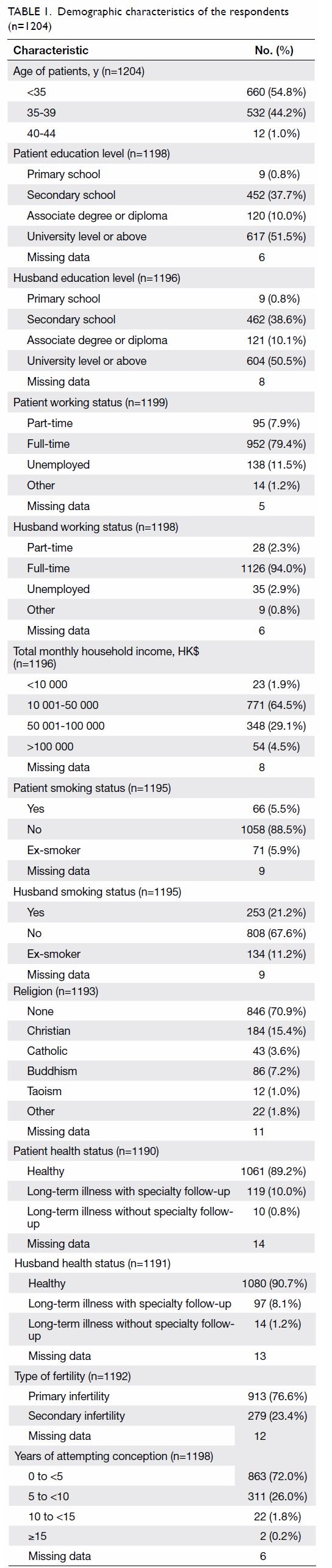

In total, 1204 questionnaires were returned (Table 1):

175 (14.5%) from Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern

Hospital, 510 (42.4%) from Queen Mary Hospital,

293 (24.3%) from Kwong Wah Hospital, 146 (12.1%)

from Prince of Wales Hospital, and 80 (6.6%) from

the FPA. The mean age (±standard deviation) of

the respondents was 34.7±6.8 years. Among the

1204 respondents, 913 women (76.6%) had primary

infertility and 279 women (23.4%) had secondary

infertility. Thirty one women had an existing child.

All respondents indicated that they were married;

the shortest duration was 0.2 years. This finding was

presumably influenced by the marriage requirement

for intrauterine insemination (IUI) and in vitro

fertilisation (IVF) in Hong Kong. Concerning the

duration of attempted conception, 863 women

(72.0%) had been actively trying for fewer than

5 years, 311 women (26.0%) had been actively trying

for 5 years to fewer than 10 years, 22 women (1.8%)

had been actively trying for 10 years to fewer than

15 years, and two women (0.2%) had been actively

trying for 15 years or more.

There were missing data in our study involving

non-responses to some questionnaire components.

The missing data exhibited a random pattern and

did not cluster around a particular question. Because

the number of missing values was small (<5%), these

values were omitted from further analyses.

Reproductive history and attitudes

concerning fertility

Overall, 1051 respondents (87.3%) reported

unremarkable medical histories. The cause of

infertility was unexplained in 516 respondents

(43.0%, 516/1200), related to the male partner in

216 respondents (18.0%, 216/1200), caused by a

tubal factor in 181 respondents (15.1%, 181/1200),

and caused by anovulation in 103 respondents (8.6%,

103/1200). The remaining respondents noted that

infertility was attributed to endometriosis, other

factors, or unknown (ie, no previous consultation).

Notably, 578 respondents (48.0%, 578/1204) or

their partners were unwilling to accept adoption.

When asked to rank the importance of having a

child, 382 respondents (31.7%, 382/1204) reported

a score of 10/10 (very important). Furthermore,

300 respondents (24.9%, 300/1204) reported that

having a child was very important to their marital

relationship (score of 10/10). Finally, 351 respondents

(29.2%, 351/1204) felt that having a child was very

important to their family members (score of 10/10).

Use of cross-border reproductive care and

factors affecting its use

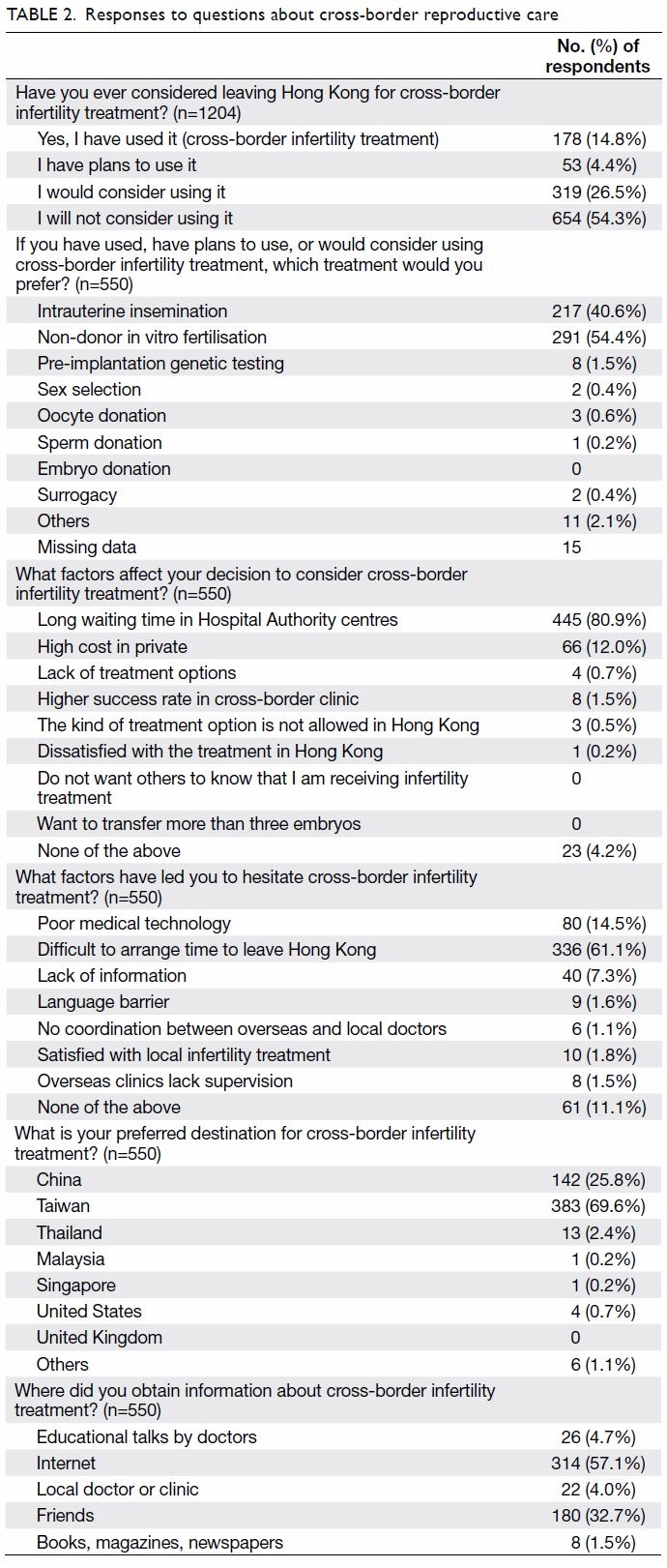

In total, 178 women (14.8% of total respondents) had used CBRC (Table 2). Among respondents who had

not used CBRC, 36.3% (372/1026) were planning

or would consider it. The 550 respondents who had

previously used CBRC, were planning for CBRC, or

would consider CBRC were then asked to choose

one reproductive technology that they preferred for

use in CBRC; 54.4% selected non-donor IVF as their

treatment of choice. In all, 40.6% of these respondents

showed interest in IUI; only 0.6% showed interest

in oocyte donation, 0.2% showed interest in sperm

donation, and 0.4% showed interest in surrogacy for

CBRC.

The two main factors positively influencing

its use (ie, motivational factors) were long waiting

times in the public sector and high treatment costs

in the private sector, reported by 80.9% (445/550)

and 12.0% (66/550), respectively, of the respondents

who had used or would consider CBRC. Only 0.5%

(3/550) of the respondents reported law evasion as a

positive influence for the use of CBRC.

Most respondents indicated that Taiwan was

their preferred destination (69.6%; 383/550); China

was the second-most preferred destination (25.8%;

142/550).

Most respondents who had used or would

consider CBRC (61.1%; 336/550) felt that it was

difficult to allocate time for CBRC. In total, 14.5%

of these respondents (80/550) had a suspicion of

substandard medical technology in the destination

countries. Some respondents were worried about

a language barrier and the lack of communication

between local doctors and doctors in the destination

countries.

Source of information

Respondents accessed information concerning

CBRC through multiple channels (Table 2). Among

the respondents who had used or would consider

CBRC, more than half (57.1%; 314/550) accessed

information from the internet; 32.7% (180/550)

obtained relevant information from their friends.

Notably, only 4.0% of these respondents (22/550)

obtained information concerning CBRC from

professional sources (eg, local fertility clinics).

Fertility treatment during cross-border

reproductive care

Among respondents who had used or would

consider CBRC (n=550), 340 (61.8%) indicated that

they had received local counselling from their home

country to assist in CBRC treatment. Among the

178 respondents who had previously used CBRC, 67

(37.6%) had some involvement from local doctors in

their home country during CBRC treatment.

Among respondents who had engaged in CBRC

and reached the point of embryo transfer (n=59),

40 (67.8%) had undergone transfer of two embryos.

Surprisingly, 10 women (16.9%) had undergone transfer of three embryos and three women (5.1%)

had undergone transfer of four embryos.

Among the 178 respondents who had used

CBRC, three (1.7%) had ovarian hyperstimulation

syndrome and three (1.7%) had other types of

complications. Overall, 70.2% of the respondents

believed that the authorities in Hong Kong should

formulate some regulations or guidance regarding

CBRC.

Respondent characteristics influencing use of

cross-border reproductive care

Associations between attitudes towards CBRC and

background variables were also explored using

the Chi squared test. Respondents who had a total

monthly household income above >HK$100 000

were more likely to consider CBRC than those who had total monthly household income of ≤HK$100 000

(P<0.001). Respondents who had a university degree

or above were also more likely to consider CBRC

than those who had education below university level

(P<0.001). Respondents who had been attempting

conception for ≥5 years had a similar likelihood

of CBRC use, compared with those who had been

attempting conception for <5 years. Respondents

aged ≥35 years had a similar likelihood of CBRC use,

compared with those aged <35 years.

Logistic regression analysis of factors

potentially associated with CBRC use revealed

no relationships with respondent age, education,

years of attempting conception, or total monthly

household income.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study

concerning the use of CBRC and factors affecting

its use in Hong Kong. Nearly one in six women

with infertility had used CBRC and approximately

one-third of the respondents planned to use or

would consider it. The main factors influencing the

likelihood of CBRC use, instead of local reproductive

care, included long waiting times in the public sector

and high cost in the private sector. Over half of the

respondents accessed information from the internet.

More than two thirds of respondents believed that

the authorities in Hong Kong should formulate some

regulations or guidance regarding CBRC.

Comparison with other regions

It is difficult to compare the use of CBRC in Hong

Kong with that in Europe (5%) and the US (4%); the

methodologies have differed among studies and the

extent of CBRC use in Hong Kong was not fully

established in the present study. Where women in

Europe frequently engage in CBRC for purposes of

law evasion, women in Hong Kong appear to engage

in CBRC primarily because of the long waiting lists

for public fertility treatment. In a survey of European

women, law evasion was a concern for 55% of

women using CBRC (9% of patients in the UK, 65%

in France, 71% in Italy, and 80% in Germany).12

Specific assisted reproduction treatment, such as

surrogacy or oocyte donation, is prohibited in some

countries (eg, Italy, Germany, and Japan), but legal

in other countries (eg, Belgium, India, and the US).

We found that only 0.5% of women in Hong Kong

travelled for purposes of law evasion. This may be

partly explained by the legal availability of gamete

donation and surrogacy in Hong Kong (although

no treatment centres in Hong Kong an appropriate

licence to offer surrogacy). Because of differences in

cultural backgrounds, compared with prior studies,

women in Hong Kong may be less interested in

gamete donation (eg, in relation to their traditional

Chinese beliefs).

Fertility treatment options

Surprisingly, many respondents in our study

engaged in IUI during CBRC. Among respondents

in this subgroup, the two main motivational factors

were identical: long waiting times in the public

sector and high treatment costs in the private sector.

The waiting time for IUI in public hospitals within

the Hospital Authority may be longer than many

patients prefer; this includes the waiting time for

the initial consultation, required examinations,

and subsequent waiting list for IUI treatment. The

treatment cost of IUI is much lower than that of IVF

in the private sector, but may be prohibitive for many

patients from lower and middle social classes. We

also acknowledge possible misconceptions among

our respondents, who may presume that IUI is

always the first-line approach or must be performed

prior to IVF.

Among women who had previously engaged

in non-donor IVF during CBRC, 33.1% were

aged <35 years. Among all the respondents who

engaged in CBRC, 30% of the respondents were

aged <35 years and had unexplained infertility.

Given the large percentage of young women with

unexplained infertility who actually engaged in

IVF during CBRC, it is unclear whether there is

an overtreatment problem or inappropriate use

of IVF treatment during CBRC. However, the

treatment of unexplained infertility is empirical.

A recent Cochrane systemic review revealed

insufficient evidence for differences in live birth

between expectant management and the other four

interventions (ovarian stimulation, IUI, stimulated

IUI, and IVF).15 For most couples, the American

Society of Reproductive Medicine recommends that

the preferred initial therapy is three or four cycles

of ovarian stimulation with oral medications and

IUI, followed by IVF for those unsuccessful with

stimulated IUI treatments.16 In contrast, the 2013

guidelines of the National Institute for Health and

Care Excellence recommend IVF treatment for

women with unexplained infertility who have not

conceived after 2 years of regular unprotected sexual

intercourse. Therefore, stimulated IUI and IVF are

both appropriate treatment options for unexplained

infertility as the first-line therapy after adequate

counselling.17

Pre-implantation genetic testing is increasingly

used to detect genetic abnormalities in embryos,

thus allowing replacement with normal embryos.

Pre-implantation genetic testing is useful when

prospective parents either have or are carriers of a

genetic disease that is potentially transmissible to

their offspring. A small proportion of the patients

in our study (1.5%) had engaged or were interested

in CBRC for pre-implantation genetic testing. In

Hong Kong, pre-implantation genetic testing is

permitted for medical indications and is available in Queen Mary Hospital, Prince of Wales Hospital, and

some private assisted reproduction centres. Because

it is legal and available in Hong Kong, few of our

respondents reported a desire to engage in CBRC for

pre-implantation genetic testing. A small percentage

of patients (0.4%) reported a desire to engage in

CBRC for sex selection. Notably, sex selection of

embryos for non-medical reasons is prohibited in

Hong Kong and many Western countries; however,

it is allowed in the US.

Destinations and sources of information

Our results found that the most popular CBRC

destination for Hong Kong couples with infertility

was Taiwan. This may be due to the presence of

Taiwanese agencies established in Hong Kong who

provide local couples with the option of going to

Taiwan to undergo CBRC. It may also be associated

with the close proximity, relatively lower costs, and

potential family ties involving Taiwan.

Importantly, we found that the internet was

the major source of information for women in

Hong Kong seeking CBRC. Women who intended

to go abroad sought information concerning CBRC

primarily via the internet, rather than from their

local doctors or fertility clinics. This phenomenon is

consistent with the findings in another study, which

reported that the internet was the main source

of information for Swedish, German, and British

women seeking CBRC.12

Multiple births

For respondents who had engaged in CBRC and

reached the point of embryo transfer, the majority

had undergone transfer of two embryos. An alarming

result of our study was that one of the patients

had undergone transfer of four embryos. High-order

multiple pregnancies can potentially cause

significant morbidity and mortality for the mother

and the baby. To reduce the likelihood of multiple

births, some countries/places (eg, the United

Kingdom and Hong Kong) have placed restrictions

on the number of embryos transferred during each

cycle. A previous survey found that 14 countries had

an upper limit of three embryos, 12 had a limit of four,

and six had a limit of five.18 This indicates that CBRC

may pose an increasing challenge for obstetricians

and paediatricians due to the increasing likelihood

of higher multiple pregnancies from CBRC, which

indirectly leads to a burden on the local healthcare

system. Clinicians should remind patients about the

implications of the number of embryos transferred

during CBRC and the potential risk of multiple

pregnancy.

Benefits and challenges involving cross-border

reproductive care

Potential advantages to CBRC include that it provides an equal opportunity for treatment, thus improving

patient autonomy; however, that autonomy may

come at a cost or involve law invasion. Cross-border

reproductive care also illustrates the principle of

freedom of patient movement, as set out in a 2008

Directive of the European Commission.19

The largest potential problem related to CBRC

involves patient health and safety. In the context of

assisted reproduction treatment, this could include

multiple pregnancies, ovarian hyperstimulation

syndrome, and infectious disease transmission.

The lack of uniform clinical and safety regulations

worldwide is further complicated by the lack of

policies to govern CBRC. This could mean that

patients are disadvantaged, such that they cannot

receive information or services that are of a minimum

quality standard. The lack of knowledge provided

to patients could inhibit their ability to discover

potential services. It is often difficult for a patient

to assess the standard of quality of a fertility clinic

in another country, in terms of infection screening

measures, embryology laboratory quality, and risk

management measures (eg, gamete and embryo

handling). Therefore, patients assume greater risk

when they engage in CBRC, compared with fertility

treatment in their home country, because of the

difference in accessible information. The safety of

women in Hong Kong who travel abroad for fertility

treatment is jeopardised by the current lack of

uniform clinical and safety regulations in other parts

of the world.

Strategies to reduce risks associated with

cross-border reproductive care

Strategies to minimise the negative impact of CBRC

should focus on each of the relevant stakeholders:

patients, clinicians, and local regulatory bodies. First,

patients who are interested in CBRC should obtain

more information prior to engaging in CBRC. They

should be aware of the potential complications and

the success rate in the destination country centre,

then make informed choices for themselves when

embarking on fertility treatment in another country.

Second, clinicians must educate their patients

about the potential risks of CBRC. Clinicians who

are collaborating with doctors in other countries

to facilitate in CBRC should formulate a clear plan

concerning the role of patient management, ensuring

that patients’ best interests are respected. Clinicians

should also resume care of a patient who has

returned after receiving CBRC treatment, especially

if that patient has encountered complications from

fertility treatment during CBRC. Third, in Europe,

the European Society of Human Reproduction and

Embryology has published a good practice guide

for CBRC for centres and practitioners.2 Such

guidelines can help regulators and policy makers

create a framework to enable centres to abide by these rules. The Hong Kong SAR Government can

also formulate guidance for clinicians and publish

advice for patients who are considering CBRC,

particularly highlighting the potential problems of

CBRC. Over two thirds of respondents in the present

study believed that authorities in Hong Kong should

formulate some regulations or guidance regarding

CBRC.

Limitations and implications

This study had a number of limitations. First, it

included patients with infertility who were not

pregnant at the time of consultation. Patients who

had a successful pregnancy following CBRC would

not attend infertility clinics; hence, they would not

be included in our sample. This could have led to

an underestimation of the use of CBRC. Second,

this study only involved heterosexual couples who

were legally married, which was a prerequisite for

receiving assisted reproduction in Hong Kong. The

study did not include single women, single men,

or same-sex couples in Hong Kong who probably

engaged in CBRC for gamete donation or surrogacy.

Third, the infertility centres in this study cannot be

considered representative of all infertility centres in

Hong Kong. A relatively small number of patients

were recruited. A territory-wide study should be

performed to further evaluate the state of CBRC in

Hong Kong.

Notably, the European Society of Human

Reproduction and Embryology recognises that ideal

reproductive care involves fair access to good quality

treatment in a patient’s home country.2 To ensure fair

access to infertility care in Hong Kong, the waiting

lists in the public sector should be shortened. Based

on the results of this questionnaire study, the current

CBRC trend in Hong Kong will presumably continue

until the local health authorities implement more

effective measures to manage the long waiting lists

in the public sector. Patient education on this topic

should also be improved.

Conclusion

Nearly one in six women with infertility in Hong

Kong had used CBRC. Among women who had not

used CBRC, more than one third had planned to use

or would consider it. The main factors influencing

the likelihood of using CBRC instead of local

reproductive care included long waiting times in

the public sector and high cost in the private sector.

These results will help clinicians to more effectively

counsel patients considering CBRC and facilitate

infertility services planning by authorities in Hong

Kong.

Author contributions

Concept or design: DYT Ng, EHY Ng.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: DYT Ng, EHY Ng.

Drafting of the manuscript: DYT Ng, EHY Ng.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: DYT Ng, EHY Ng.

Drafting of the manuscript: DYT Ng, EHY Ng.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to Ms Merie Yuen,

project nurse of University of Hong Kong for data collection

and entry.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards

of all participating centres, including the Hong Kong East

Cluster Ethics Committee (HKECREC-2018-014); The

University of Hong Kong Hong Kong West Cluster Clinical

Research Ethics Committee (UW 18-266); Kowloon Central/Kowloon East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee

(KC/KE-18-0073/ER-4); North Territories East Cluster

Clinical Research Ethics Committee (NTEC-2018-0384); and

the Ethics Panel and the Health Services Subcommittee of the

FPAHK (OA1-2).

All participants provided written informed consent to

participate in the questionnaire study.

References

1. Inhorn MC, Patrizio P. The global landscape of cross-border reproductive care: twenty key findings for the new

millennium. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2012;24:158-63. Crossref

2. Shenfield F, Pennings G, de Mouzon J, Ferraretti AP,

Goossens V, ESHRE Task Force ‘Cross Border Reproductive

Care’ (CBRC). ESHRE’s good practice guide for cross-border

reproductive care for centers and practitioners.

Hum Reprod 2011;26:1625-7. Crossref

3. Inhorn MC, Patrizio P. Rethinking reproductive ‘‘tourism’’

as reproductive ‘‘exile’’. Fertil Steril 2009;92:904-6. Crossref

4. Mattorras R. Reproductive exile versus reproductive

tourism. Hum Reprod 2005;20:3571. Crossref

5. Culley L, Hudson N, Rapport F, Blyth E, Norton W,

Pacey AA. Crossing borders for fertility treatment:

motivations, destinations and outcomes of UK fertility

travellers. Hum Reprod 2011;26:2373-81. Crossref

6. Gomez VR, de La Rochebrochard E. Cross-border

reproductive care among French patients: experiences in

Greece, Spain and Belgium. Hum Reprod 2013;28:3103-10. Crossref

7. Gürtin ZB. Banning reproductive travel: Turkey’s ART

legislation and third party assisted reproduction. Reprod

Biomed Online 2011;23:555-64. Crossref

8. Bergmann S. Reproductive agency and projects: Germans

searching for egg donation in Spain and the Czech

Republic. Reprod Biomed Online 2011;23:600-8. Crossref

9. Hughes EG, Dejean D. Cross-border fertility services

in North America: a survey of Canadian and American

providers. Fertil Steril 2010;94:e16-9. Crossref

10. Inhorn MC, Shrivastav P, Patrizio P. Assisted reproductive

technologies and fertility ‘‘tourism”: examples from global

Dubai and the Ivy League. Med Anthropol 2012;31:249-65. Crossref

11. Yuri H, Yosuke S, Yasuhiro K, Yoshiaki H, Hiroyuki N.

Attitudes towards cross-border reproductive care among

infertile Japanese patients. Environ Health Prev Med

2013;18:477-84. Crossref

12. Shenfield F, de Mouson J, Pennings G, et al. Cross border

reproductive care in six European countries. Hum Reprod

2010;25:1361-8. Crossref

13. Hudson N, Culley L, Blyth E, Norton W, Rapport F,

Pacey A. Cross-border reproductive care: a review of the

literature. Reprod Biomed Online 2011;22:673-85. Crossref

14. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and

Health Promotion, Division of Reproductive Health, US

Government. 2013 Assisted reproductive technology:

national summary report 5 (2015). Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/art/pdf/2013-report/art_2013_national_summary_report.pdf. Accessed 4 Dec 2019.

15. Wang R, Danhof NA, Tjon-Kon-Fat RI, et al. Interventions

for unexplained infertility: a systematic review and

network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2019;(9):CD012692. Crossref

16. Practice Committee of the American Society for

Reproductive Medicine. Evidence-based treatments for

couples with unexplained infertility: a guideline. Fertil

Steril 2020;113:305-22. Crossref

17. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s

Health (UK). Fertility: Assessment and Treatment for

People with Fertility Problems. London: Royal College of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2013.

18. International Federation of Fertility Societies. Global

Reproductive Health: IFFS Surveillance 2016. September

2016. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/grh/Fulltext/2016/09000/IFFS_Surveillance_2016.1.aspx. Accessed 4 Dec 2019.

19. Commission of the European Communities. Proposal

for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the

Council on the application of patients’ rights in cross-border

healthcare. 2008. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_overview/co_operation/healthcare/docs/COM_en.pdf. Accessed 4 Dec 2019.