Hong Kong Med J 2020 Oct;26(5):413–20 | Epub 17 Sep 2020

Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE CME

Labour analgesia: update and literature review

KK Lam, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology); May KM Leung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology); Michael G Irwin, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)

Department of Anaesthesiology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KK Lam (dr.patricklam.hk@gmail.com)

Abstract

Pain relief is an important component of modern

obstetric care and can be produced by neuraxial,

systemic, or inhalational analgesia or various physical

techniques. We review the most recent evidence on

the efficacy and safety of these techniques. Over the

past decade, the availability of safer local anaesthetics,

ultra-short acting opioids, combined spinal-epidural

needles, patient-controlled analgesic devices, and

ultrasound have revolutionised obstetric regional

analgesia. Recent meta-analyses have supported

epidural analgesia as the most efficacious technique,

as it leads to higher maternal satisfaction and good

maternal and fetal safety profiles. We examine the

controversies and myths concerning the initiation,

maintenance, and discontinuation of epidural analgesia. Recent evidence will also be reviewed

to address concerns about the effects of epidural

analgesia on the rates of instrumental and operative

delivery, lower back pain, and breastfeeding. New

developments in labour analgesia are also discussed.

Introduction

Labour pain is so notoriously painful that opium

and its derivatives have been used in childbirth for

several thousand years, along with numerous folk

medicines and remedies. Nulliparous women suffer

greater sensory pain during the early stage of labour

compared with multiparous women, for whom the

second stage is more intense.1 Labour pain has both

visceral and somatic components.2 The first stage of

labour pain is caused by contraction of the uterus

and gradual dilatation of the cervix. The visceral pain

is carried by small unmyelinated C-fibres through

sympathetic nerves to the T10 to L1 segments of

the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. The pain is often

referred to as located in the front and back of the

lower abdomen and sacrum. Stretching of the

vaginal wall, perineum, and vaginal surface of the

cervix in the later stage of labour causes ischaemic

pain, which is conducted through thick myelinated

A fibres in the pudendal and perineal branches of the

posterior cutaneous nerve in the thigh to the S2 to

S4 nerve roots, Thus, women who are giving birth

feel sharp somatic pain in the perineum.

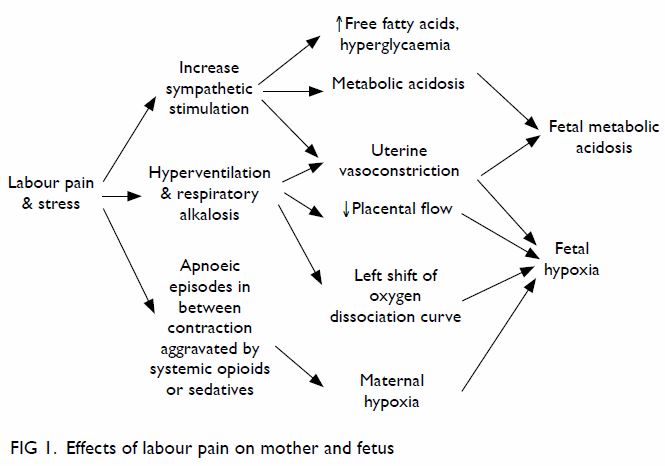

As well as being unpleasant, labour pain may

have harmful effects on the mother and baby,1 3 as pain

stimulates catecholamine release, which constricts

the uterine blood vessels. Pain also causes maternal

hyperventilation, resulting in hypocapnia, which

further constricts the uterine vessels and decreases

the mother’s ventilatory drive between contractions,

thereby causing the left shift of the maternal oxygen

dissociation curve. These factors compromise oxygen

supply to the fetus and can lead to fetal hypoxaemia and fetal metabolic acidosis (Fig 1). Premature

‘bearing down’ can also lead to birth canal trauma

and birth injury. Parenteral opioids can exacerbate

maternal respiratory depression, whereas regional

analgesia can reduce the adverse effects of labour

pain on respiration and the sympathetic nervous

system. Therefore, good labour analgesia should

aim not only to relieve the pain and suffering of the

mother but also to decrease fetal acidosis and make

the delivery process safer for both the mother and

baby. Traditionally, pain relief methods are classified

into non-pharmacological, pharmacological, and

regional techniques. In this article, we examine the

most recent evidence on the efficacy and safety of

the commonly available methods.

Non-pharmacological techniques

Mild labour pain may be reduced by massage,

psychological relaxation techniques, transcutaneous

electrical nerve stimulation, aromatherapy, hypnosis,

sterile water injection, acupuncture, deep breathing,

and hydrotherapy. However, most of the evidence

on non-drug interventions is based on anecdotal

reports from a small number of studies. A Cochrane

systematic review reported that immersion and

relaxation produced good satisfaction, and both

relaxation and acupuncture decreased the use

of forceps and ventouse, with acupuncture also

decreasing the number of Caesarean sections.4

There was insufficient evidence to judge whether or

not hypnosis, biofeedback, sterile water injection,

aromatherapy, and transcutaneous electrical nerve

stimulation are effective.4

Pharmacological techniques

Entonox is a mix of 50% nitrous oxide in oxygen

that has been in use for a long time. It has some

analgesic efficacy, but many women who used it

felt drowsy, nauseous, or were sick.4 Nitrous oxide

has detrimental effects on vitamin B12 metabolism,

and there are valid concerns about occupational

exposure to healthcare professionals in the delivery

suite, although the use of a proper scavenging system

can help. It has the advantage of being easy to use

by self-administration, but around 30% to 40% of

patients found pain relief inadequate with Entonox

alone.5

Sub-anaesthetic doses (0.8% in oxygen) of

sevoflurane have been evaluated as an alternative

to Entonox.6 7 In those studies, despite its lack of

analgesic effects and increased level of sedation,

most women preferred it to Entonox. It also caused

less nausea and vomiting than Entonox. However, there are valid concerns about loss of consciousness,

fetal toxicity, and air pollution; therefore, it is not

popular.

Intramuscular pethidine is widely prescribed.

Pethidine is a potent opioid, making the side-effects

of somnolence, nausea, vomiting, and respiratory

depression common. It is less effective than epidural

analgesia4 and cannot be given near the end of the

first stage or during the second stage of labour

because of its respiratory depressant effects on

the baby. It also has a neuroexcitatory metabolite,

norpethidine.

Remifentanil, an ultra-short acting opioid with

a half-life of about 3 minutes irrespective of the

duration of infusion, is usually given intravenously

using a patient-controlled analgesic pump. In 2001,

we found that the time to first request for rescue

analgesia and maternal satisfaction were higher with

patient-controlled analgesic remifentanil compared

with intramuscular pethidine. There was no sedation,

apnoea, or oxygen desaturation in either group, and

Apgar scores of the groups were similar.8 In 2018, the

RESPITE trial showed that remifentanil halved the

proportion of epidural conversions compared with

intramuscular pethidine.9 The pooled risk ratio for

rescue analgesia of remifentanil relative to pethidine

was 0.54. The study also reported that remifentanil

posed no excessive risk of respiratory depression to

the mothers or babies, thus challenging pethidine’s

routine use as a first-line opioid in the management

of labour pain. Although its analgesia is not superior

to an epidural, remifentanil is an efficacious

alternative for patients who have contra-indications

to epidural administration, including back problems,

coagulopathy, and fixed cardiac output diseases.

Many local and overseas centres have incorporated

this option into their labour pain management

programmes. The RemiPCA SAFE Network has

been established to set standards and monitor

maternal and fetal outcomes when remifentanil is

used for labour analgesia.10

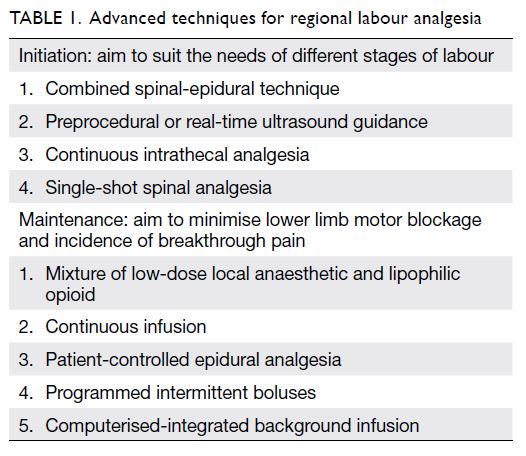

Neuraxial analgesic techniques

Epidural analgesia, introduced in the 1960s, is still

the most effective method of labour pain relief.11 It

involves placing a very fine catheter into the epidural

space for repeat boluses or continuous infusion of

local anaesthetics. This allows for continuous pain

relief throughout labour and ‘top-up’ boluses, if

required, for operative deliveries. New drugs and

technological advancements have improved safety,

and our understanding of its effects on obstetric

outcomes has been revised (Table 1). Levobupivacaine and

ropivacaine are the newest amide local anaesthetics,

and they are less cardiotoxic than bupivacaine.

Traditionally, a high concentration of local

anaesthetic (eg, 0.2%-0.25% bupivacaine) has been

used to maintain labour epidural analgesia. Over the years, the adoption of a lower concentration of local

anaesthetic (0.0625%-0.1%) and lipophilic opioids

(fentanyl or sufentanil) has lessened side-effects

such as motor blockage and hypotension.12 These

drugs have made it possible for women to walk or

move around more easily in bed and retain a mild

sensation of uterine contraction and urgency of

bearing down, thereby facilitating pushing the baby

out in the second stage of labour. In the Comparative

Obstetric Mobile Epidural Trial study, the use of

low-dose infusion significantly reduced the incidence

of assisted vaginal delivery.13 Meta-analysis showed

that a lower concentration of local anaesthetic

reduces the incidence of assisted vaginal delivery

and urinary retention and shortens the second stage

compared with a higher concentration.14 A 2018

Cochrane review stated that this type of epidural

analgesia has no adverse impact on the proportions

of Caesarean section, long-term backache, or

neonatal outcomes.11

Combined spinal-epidural technique

In the ‘needle-through-needle’ combined spinal-epidural

(CSE) technique, a 25- or 27-G pencil

point spinal needle with a locking device is inserted

through the epidural needle that allows the

deposition of a small dose of local anaesthetic, with

or without opioids, into the cerebrospinal fluid in

the intrathecal space. The onset of analgesia is rapid.

An epidural catheter is then threaded through the

epidural needle after withdrawing the spinal needle.

A review of the complications has concluded that

CSE is equally safe to a conventional epidural.15

The use of CSE has increased relative to that of the

conventional epidural technique, as it has a quicker

onset of analgesia in mothers with severe pain,

those in the advanced stage of labour, and those

who are multiparous. The technique also improves

the success of correct functioning epidural catheter

placement by prior verification of placement in the

subarachnoid space with the spinal needle.16 Despite

the increasingly widespread use of this technique

and numerous published investigations, the

optimal intrathecal drug regimen has not yet been

determined. The disadvantage of CSE is immediate

uncertainty about whether the epidural is working

because of the initial effects of spinal analgesia.

However, a 2016 study refuted this and favoured CSE

earlier detection of failed epidural analgesia.17 The

use of a 27-G spinal needle is preferred, as its small

size is associated with a lower risk of post-dural

puncture headache.18 Although there is faster onset

of analgesia, the effects on maternal satisfaction

are controversial. A systematic review found

no differences in maternal satisfaction, mode of

delivery, or ambulatory ability between CSE and the

conventional epidural technique.19 Subsequently,

the choice between conventional epidural and CSE has often been dictated by the clinical situation,

institutional protocols, available equipment, and

practitioner preference/experience.

Continuous intrathecal technique

In continuous intrathecal labour analgesia, local

anaesthetic with or without opioids is directly

deposited into the intrathecal space using a 23- to

28-G microcatheter. This technique can provide

rapid analgesia or anaesthesia and higher maternal

satisfaction with less use of local anaesthetic, but it

is also associated with more technical difficulties and

catheter failure compared with epidural analgesia. It

is theoretically advantageous in the management of

morbidly obese patients, patients with significant

co-morbidities who cannot tolerate haemodynamic

instability, and patients with potentially difficult

airways who undergo Caesarean section, as it allows

gradual titration and slower onset of subarachnoid

blockage.20 This technique is still uncommonly used

because of various concerns including post-dural

puncture headache and neuraxial infection. Further

studies are required to assess whether it can assist

in the management of patients with conditions that

make neuraxial labour analgesia challenging.

Maintenance of neuraxial analgesia

Once an epidural catheter is placed, analgesia

can be maintained by intermittent top-ups,

continuous infusion, patient-controlled analgesia, or

programmed intermittent epidural boluses (PIEB).

Continuous infusion technique became popular

in the early 1980s. This delivery method reduced

the variability of analgesia during labour, especially

when high concentrations of local anaesthetics were

replaced by low concentrations with the addition of

a lipophilic opioid. Unfortunately, this modality does

not suit all patients despite many combinations of infusion rate, local anaesthetic concentration, and

additives having been investigated. Many patients

still require clinician-initiated top-ups or experience

unacceptable motor blockage.

Patient-controlled epidural analgesia

Patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) was

first described in 1988.21 Boluses of 4 to 8 mL of

epidural mixture are delivered on patient demand

with a lockout interval of 10 to 20 minutes. As labour

pain has highly variable intensity, and the character

of the pain often changes as it progresses, it makes

sense that patients may be the best managers of

their own pain relief. There is recent evidence that

genetic polymorphism may also affect the patient’s

labour progress and response to labour analgesia.

One example is the Mu opioid receptor gene

single-nucleotide polymorphism (OPRM1, A118G),

which is believed to be present in 30% of women

in labour and may affect the response to neuraxial

opioids.22 23 Administration of PCEA allows for

some self-titration. Over the past 20 years, PCEA

has been widely studied and the technique refined.

High-volume, dilute local anaesthetic solutions

with a continuous background infusion appear

to be the best PCEA regimen.24 The American

Society of Anesthesiologists practice guidelines

for obstetric anaesthesia advise that basal infusion

improves analgesia when provided as part of a PCEA

regimen.25 Studies have also shown that PCEA

requires less anaesthesia intervention, lower doses of

local anaesthetic, and produces less motor blockage

than continuous epidural infusion.26 27 Although

PCEA delivery devices tend to be more expensive

than continuous infusion pumps, the technique may

have important benefits. The optimum method of

administration requires communication with both

the midwife and the patient.

Computer-integrated patient-controlled

epidural analgesia

An alternative approach to determining the

background infusion rate during PCEA is the use of

a computer programme to automatically adjust the

background infusion rate according to the amount of

local anaesthetic used in the previous hour. A laptop

computer is connected to a PCEA pump. In theory,

a system that responds to a patient’s analgesic

requirements should improve efficacy while

minimising the amount of local anaesthetic used

for background infusions. Initial studies with this

system have been encouraging. In a study comparing

demand-only PCEA with computer-integrated

background infusion PCEA (CIPCEA), the CIPCEA

group had similar local anaesthetic consumption

but increased maternal satisfaction.28 Another

study found that CIPCEA reduced the incidence of breakthrough pain without increasing drug

consumption compared with continuous epidural

infusion.29 When CIPCEA was compared with PCEA

using fixed-rate continuous infusion, the CIPCEA

group had higher maternal satisfaction, whereas

local anaesthetic consumption, visual analogue pain

scores, and incidence of breakthrough pain were

similar between the two groups.30 Therefore, an

adjustable background infusion appears to increase

maternal satisfaction and may further reduce the

incidence of breakthrough pain without increasing

local anaesthetic consumption.

Programmed intermittent epidural boluses

Programmed intermittent epidural boluses is a novel

technology in which boluses of epidural mixture

are delivered at predetermined intervals. Improved

analgesia may be offered by PIEB, as the local

anaesthetic is administered in boluses under high

driving pressure, which can disperse the solution

more widely than continuous infusion31 with multi-orifice

catheters.32 A system has been developed

in which a computer delivers both automated and

manual boluses. The authors demonstrated that

this ‘programmed intermittent mandatory epidural

bolus’ with a PCEA regimen provided advantages

over a PCEA plus background infusion regimen:

the former used less local anaesthetic dose, but

resulted in a higher maternal satisfaction and a

longer duration of analgesia. However, there was

no difference in the incidence of breakthrough

pain between the two groups.33 34 In 2012 and 2014,

respectively, Health Canada and the United States

Food and Drug Administration approved PIEB

combined with PCEA (CADD Solis Epidural Pump,

Smiths Medical, St Paul [MN], United States) for

clinical use.35 A 2013 systematic review investigating

PIEB for maintenance of labour analgesia that

included nine randomised controlled trials with

694 patients36 showed that the vast majority of

studies associated PIEB with decreased local

anaesthetic consumption, improved maternal

satisfaction scores, decreased instrumental delivery,

and lessened need for anaesthesia intervention. A

recent trial confirmed that reduced motor blockage

was associated with PIEB,37 although that study

could not identify other significant outcomes.

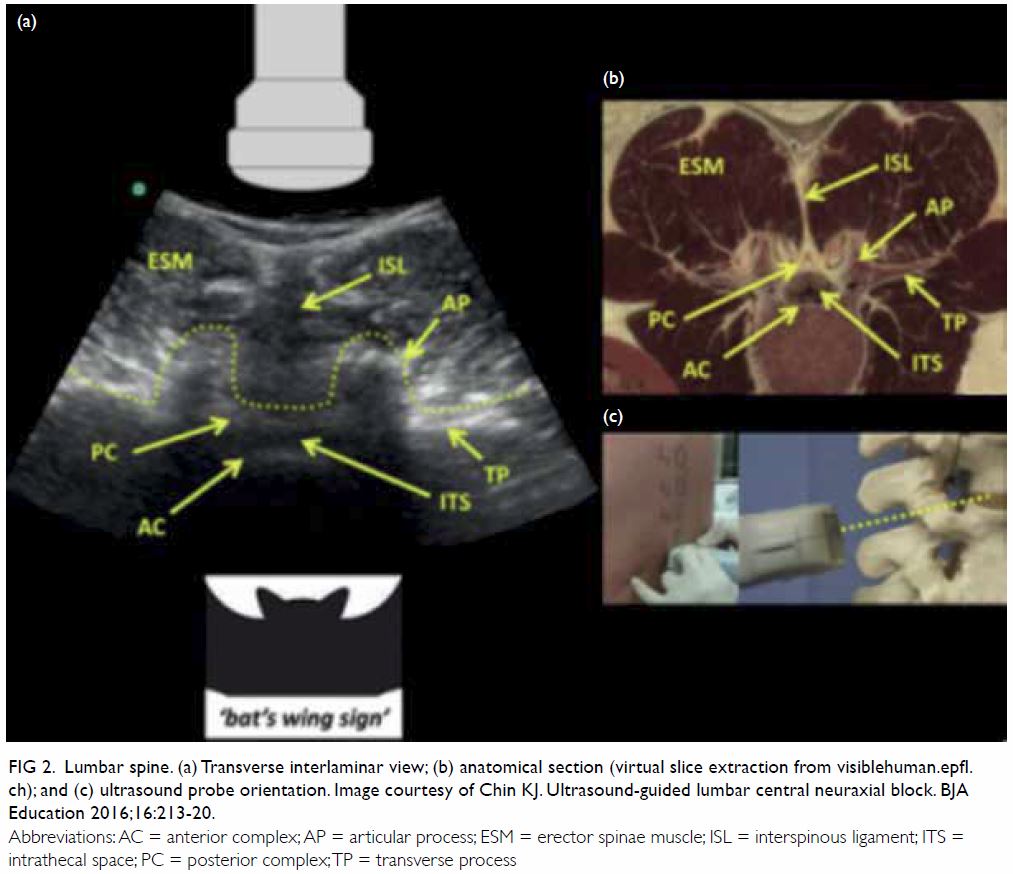

Ultrasound

Although ultrasound is widely used in the placement

of central venous catheters and peripheral nerve

blockage, it is less commonly used in neuraxial

analgesia for obstetric patients. It can be used either

before the procedure to study the site of needle

entry and the depth of the epidural space or for

real-time needle guidance (Fig 2). Although the

preprocedural use of ultrasound in normal pregnant mothers seems to have limited efficacy among both

experienced clinicians38 and trainees,39 some study

findings have suggested that it is a useful tool40 to

consider in obese patients41 or those with lumbar

spine problems. In 2008, the United Kingdom’s

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

determined that sufficient evidence had been

published to support the routine use of ‘ultrasound to

facilitate the catheterisation of the epidural space’.42

In March 2016, the American Society of Regional

Anesthesia and Pain Medicine43 published the second

evidence-based medicine assessment of ultrasoundguided

regional anaesthesia to ‘enable practitioners

to make an informed evaluation regarding the role

of ultrasound-guided regional anaesthesia in their

practice’. A high-quality review article by Arzola

outlined the controversies, advantages, and practical

applications of preprocedural ultrasound in obstetric

patients.44

Figure 2. Lumbar spine. (a) Transverse interlaminar view; (b) anatomical section (virtual slice extraction from visiblehuman.epfl. ch); and (c) ultrasound probe orientation. Image courtesy of Chin KJ. Ultrasound-guided lumbar central neuraxial block. BJA Education 2016;16:213-20.

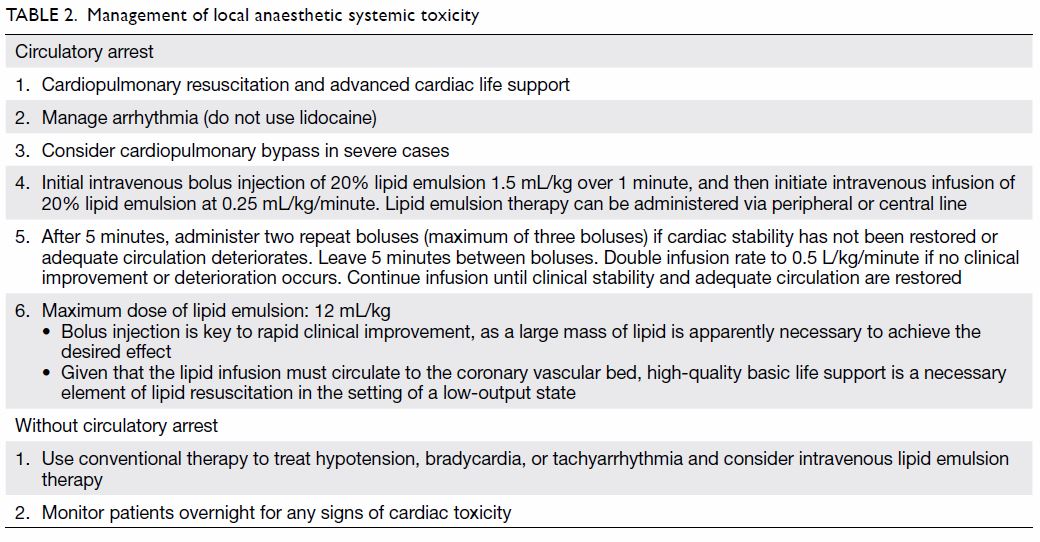

Intralipid infusion

Neuraxial analgesia is now also safer with the availability of intralipid as an antidote for local

anaesthetic toxicity.45 46 Intralipid binds with amide

local anaesthetic molecules in the plasma, thereby

decreasing the free fraction available to bind with

cardiac muscle. It has become widely adopted

as part of the resuscitation protocol for local

anaesthetic-caused systemic toxicity and should be

readily available in all delivery units where neuraxial

analgesia is practised. It is given intravenously by

boluses followed by continuous infusion according

to body weight (Table 2).

When should an epidural catheter

be sited?

Previous concerns that early epidural initiation

(when cervical dilatation <4 cm) would increase the

rate of instrumental delivery and Caesarean section

have been alleviated by more recent research.

Wong et al47 found that neuraxial analgesia in

early labour did not increase the rate of Caesarean

delivery but provided better analgesia and resulted

in a shorter duration of labour than systemic analgesia. The latest Cochrane review indicated that

there is abundant high-quality evidence that early

and late epidural initiation have similar effects on

all measured outcomes.48 The American College of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the American

Society of Anesthesiologists49 have also jointly

emphasised that there is no need to wait until

cervical dilation has reached 4 to 5 cm and stated

that ‘maternal request is a sufficient indication for

pain relief in labour’.50 When delivery is imminent,

the decision to offer regional anaesthesia should

be individualised and depends on various factors

including a woman’s parity, fetal condition, and

whether a prolonged second stage is expected, such

as malposition of the fetus or macrosomia. The Royal

College of Anaesthetists recommends that the time

from epidural request to the anaesthetist attending

should not exceed 30 minutes, after which a second

anaesthetist should be available.51

When should epidural analgesia be

terminated?

There is insufficient evidence to support the

discontinuation of epidural analgesia late in labour

as a means to reduce adverse delivery outcomes.52

Doing so also increases the rate of inadequate pain

relief in the second stage of labour. A meta-analysis

of high-quality studies did not show significant

differences in outcomes with immediate and delayed

pushing in the second stage of labour.53

Other effects

The effects of neuraxial analgesia on successful

breastfeeding have been evaluated in several studies with controversial results. A recent

large, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial

showed that epidural solutions containing fentanyl

concentrations as high as 2 μg/mL did not affect

breastfeeding rates at 6 weeks postpartum.54 The

results correlated with those of another study

investigating women with previous breastfeeding

experience, as both studies showed no difference

in the breastfeeding rates at 6 weeks postpartum

between groups of women who did and did not

receive epidural analgesia.55 Therefore, factors other

than epidural and fentanyl administration can affect

the successful breastfeeding rate.

The association of maternal fever with

epidural analgesia has remained an area of clinical

and research interest.56 A 2016 expert panel defined

maternal fever as maternal temperature of ≥38°C

measured orally for two readings 30 minutes apart.57

Up to one third of mothers may be affected, and

the aetiology and prophylactic prevention are still

not well understood, although the local anaesthetic

used for epidural analgesia is a likely culprit. Sterile

inflammation and activation of inflammasomes

probably play a role,58 and this is an area of ongoing

research.59

Conclusions

Epidural analgesia remains the best method of

relieving pain during labour. Advances in technology

have made it even safer than before. In the absence of

any medical contra-indications, maternal request is

a sufficient indication to initiate epidural analgesia,

and if it is properly conducted, it can be considered

at any stage of labour without affecting the rate

of instrumental or Caesarean delivery. Future improvements may lie in preventing breakthrough

pain via interaction with various closed-loop

feedback drug delivery systems. Remifentanil-based

opioid techniques are becoming a popular alternative

if epidural is contra-indicated.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept of study, drafting of

the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for

important intellectual content. All authors had full access to

the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version

for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and

integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, MG Irwin was not involved in the peer review process of the article. The other authors have no

conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Prof Ki-jinn Chin, Associate Professor,

Department of Anesthesia, Toronto Western Hospital,

University of Toronto for permission to use the image in

Figure 2.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Labor S, Maguire S. The pain of labour. Rev Pain 2008;2:15-

9. Crossref

2. Rowlands S, Permezel M. Physiology of pain in labour.

Bailliere Clin Obstet Gynaecol 1998;12:347-62. Crossref

3. Wong CA. Advances in labor analgesia. Int J Womens

Health 2009;1:139-54. Crossref

4. Jones L, Othman M, Dowswell T, et al. Pain management

for women in labour: an overview of systematic reviews.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(3):CD009234. Crossref

5. Carstoniu J, Levytam S, Norman P, Daley D, Katz J,

Sandler AN. Nitrous oxide in early labor safety and

analgesic efficacy assessed by a double-blind, placebo-controlled

study. Anesthesiology 1994;80:30-5. Crossref

6. Yeo ST, Holdcroft A, Yentis SM, Stewart A. Analgesia

with sevoflurane during labour: i. Determination of the

optimum concentration. Br J Anaesth 2007;98:105-9. Crossref

7. Yeo ST, Holdcroft A, Yentis SM, Stewart A, Bassett P.

Analgesia with sevoflurane during labour: ii. Sevoflurane

compared with Entonox for labour analgesia. Br J Anaesth

2007;98:110-5. Crossref

8. Ng TK, Cheng BC, Chan WS, Lam KK, Chan MT. A double-blind

randomised comparison of intravenous patient-controlled

remifentanil with intramuscular pethidine for

labour analgesia. Anaesthesia 2011;66:796-801. Crossref

9. Wilson MJ, MacArthur C, Hewitt CA, et al. Intravenous

remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia versus

intramuscular pethidine for pain relief in labour (RESPITE):

an open-label, multicentre, randomised controlled trial.

Lancet 2018;392:662-72. Crossref

10. Melber AA, Jelting Y, Huber M, et al. Remifentanil patient-controlled

analgesia in labour: six-year audit of outcome data of the RemiPCA SAFE Network (2010-2015). Int J

Obstet Anesth 2019;39:12-21.Crossref

11. Anim-Somuah M, Smyth RM, Cyna AM, Cuthbert A.

Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia for pain

management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2018;(5):CD000331. Crossref

12. Sharma RM, Setlur R, Bhargava AK, Vardhan S. Walking

epidural: an effective method of labour pain relief. Med J

Armed Forces India 2007;63:44-6. Crossref

13. Comparative Obstetric Mobile Epidural Trial (COMET)

Study Group UK. Effect of low-dose mobile versus

traditional epidural techniques on mode of delivery: a

randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2001;358:19-23. Crossref

14. Sultan P, Murphy C, Halpern S, Carvalho B. The effect of

low concentrations versus high concentrations of local

anesthetics for labour analgesia on obstetric and anesthetic

outcomes: a meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth 2013;60:840-54. Crossref

15. Skupski DW, Abramovitz S, Samuels J, Pressimone V,

Kjaer K. Adverse effects of combined spinal-epidural

versus traditional epidural analgesia during labor. Int J

Gynecol Obstet 2009;106:242-5. Crossref

16. Norris MC, Fogel ST, Conway-Long C. Combined spinalepidural

versus epidural labor analgesia. Anesthesiology

2001;95:913-20. Crossref

17. Booth JM, Pan JC, Ross VH, Russell GB, Harris LC, Pan PH.

Combined spinal epidural technique for labor analgesia

does not delay recognition of epidural catheter failures:

a single-center retrospective cohort survival analysis.

Anesthesiology 2016;125:516-24. Crossref

18. Landau R, Ciliberto CF, Goodman SR, Kim-Lo SH, Smiley

RM. Complications with 25-gauge and 27-gauge Whitacre

needles during combined spinal-epidural analgesia in

labor. Int J Obstet Anesth 2001;10:168-71. Crossref

19. Simmons SW, Taghizadeh N, Dennis AT, Hughes D, Cyna AM.

Combined spinal-epidural versus epidural analgesia in

labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(10):CD003401. Crossref

20. Drasner K, Smiley R. Continuous spinal analgesia for labor

and delivery: a born-again technique? Anesthesiology

2008;108:184-6. Crossref

21. Gambling DR, Yu P, Cole C, McMorland GH, Palmer L. A

comparative study of patient controlled epidural analgesia

(PCEA) and continuous infusion epidural analgesia (CIEA)

during labour. Can J Anaesth 1988;35:249-54. Crossref

22. Landau R, Cahana A, Smiley RM, Antonarakis SE, Blouin JL.

Genetic variability of μ-opioid receptor in an obstetric

population. Anesthesiology 2004;100:1030-3. Crossref

23. Sia AT, Lim Y, Lim EC, et al. A118G single nucleotide

polymorphism of human μ-opioid receptor gene influences

pain perception and patient-controlled intravenous

morphine consumption after intrathecal morphine for

postcesarean analgesia. Anesthesiology 2008;109:520-6. Crossref

24. Halpern SH, Carvalho B. Patient-controlled epidural

analgesia for labor. Anesth Analg 2009;108:921-8. Crossref

25. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on

Obstetric Anesthesia. Practice guidelines for obstetric

anesthesia: an updated report by the American Society

of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia.

Anesthesiology 2007;106:843-63.

26. van der Vyver M, Halpern S, Joseph G. Patient-controlled

epidural analgesia versus continuous infusion for labour

analgesia: a meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2002;89:459-65. Crossref

27. D’Angelo R. New techniques for labor analgesia: PCEA and

CSE. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2003;46:623-32. Crossref

28. Lim Y, Sia AT, Ocampo CE. Comparison of computer

integrated patient controlled epidural analgesia vs.

conventional patient controlled epidural analgesia for pain

relief in labour. Anaesthesia 2006;61:339-44. Crossref

29. Sia AT, Lim Y, Ocampo CE. Computer-integrated patientcontrolled

epidural analgesia: a preliminary study on a

novel approach of providing pain relief in labour. Singapore

Med J 2006;47:951-6.

30. Sng BL, Sia AT, Lim Y, Woo D, Ocampo C. Comparison of

computer-integrated patient-controlled epidural analgesia

and patient-controlled epidural analgesia with a basal

infusion for labour and delivery. Anaesth Intensive Care

2009;37:46-53. Crossref

31. Hogan Q. Distribution of solution in the epidural space:

examination by cryomicrotome section. Reg Anesth Pain

Med 2002;27:150-6. Crossref

32. Duncan LA, Fried MJ, Lee A, Wildsmith JA. Comparison of

continuous and intermittent administration of extradural

bupivacaine for analgesia after lower abdominal surgery. Br

J Anaesth 1998;80:7-10. Crossref

33. Sia AT, Lim Y, Ocampo C. A comparison of a basal

infusion with automated mandatory boluses in parturient-controlled

epidural analgesia during labor. Anesth Analg

2007;104:673-8. Crossref

34. Leo S, Sia AT. Maintaining labour epidural analgesia: what

is the best option? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2008;21:263-9. Crossref

35. Carvalho B, George RB, Cobb B, McKenzie C, Riley ET.

Implementation of programmed intermittent epidural

bolus for the maintenance of labor analgesia. Anesth Analg

2016;123:965-71. Crossref

36. George RB, Allen TK, Habib AS. Intermittent epidural

bolus compared with continuous epidural infusions for

labor analgesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Anesth Analg 2013;116:133-44. Crossref

37. Ojo OA, Mehdiratta JE, Gamez BH, Hunting J, Habib AS.

Comparison of programmed intermittent epidural boluses

with continuous epidural infusion for the maintenance of

labor analgesia: a randomized, controlled, double-blind

study. Anesth Analg 2020;130:426-35. Crossref

38. Ansari T, Yousef A, El Gamassy A, Fayez M. Ultrasound-guided

spinal anaesthesia in obstetrics: is there an

advantage over the landmark technique in patients with

easily palpable spines? Int J Obstet Anesth 2014;23:213-6. Crossref

39. Arzola C, Mikhael R, Margarido C, Carvalho JC. Spinal

ultrasound versus palpation for epidural catheter insertion

in labour: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol

2015;32:499-505. Crossref

40. Perlas A, Chaparro LE, Chin KJ. Lumbar neuraxial

ultrasound for spinal and epidural anesthesia: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med

2016;41:251-60. Crossref

41. Creaney M, Mullane D, Casby C, Tan T. Ultrasound to

identify the lumbar space in women with impalpable bony

landmarks presenting for elective Caesarean delivery

under spinal anaesthesia: a randomised trial. Int J Obstet

Anesth 2016;28:12-6. Crossref

42. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

Interventional procedures guidance (IPG249): Ultrasound-guided

catheterisation of the epidural space. 23 Jan 2008.

43. Neal JM, Brull R, Horn JL, et al. The Second American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine

evidence-based medicine assessment of ultrasound-guided

regional anesthesia: executive summary. Reg Anesth Pain

Med 2016;41:181-94. Crossref

44. Arzola C. Preprocedure ultrasonography before

initiating a neuraxial anesthetic procedure. Anesth Analg

2017;124:712-3. Crossref

45. Kosh MC, Miller AD, Michels JE. Intravenous lipid

emulsion for treatment of local anesthetic toxicity. Ther

Clin Risk Manag 2010;6:449-51. Crossref

46. Weinberg GL. Lipid emulsion infusion: resuscitation for

local anesthetic and other drug overdose. Anesthesiology

2012;117:180-7. Crossref

47. Wong CA, Scavone BM, Peaceman AM, et al. The risk

of Cesarean delivery with neuraxial analgesia given early

versus late in labor. N Engl J Med 2005;352:655-65. Crossref

48. Sng BL, Leong WL, Zeng Y, et al. Early versus late initiation

of epidural analgesia for labour. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev 2014;(10):CD007238. Crossref

49. Lim G, Levine MD, Mascha EJ, Wasan AD. Labor pain,

analgesia, and postpartum depression: are we asking the

right questions? Anesth Analg 2020;130:610-4. Crossref

50. Rendon KL, Wheeler V. Epidural analgesia and risk

of Cesarean delivery. Am Fam Physician 2018 Nov

1;98:Online.

51. Chapter 9: Guidelines for the provision of anaesthesia

services (GPAS). Guidelines for the Provision of

Anaesthesia Services for an Obstetric Population. Royal

College of Anaesthetists; 2020: 9.

52. Torvaldsen S, Roberts CL, Bell JC, Raynes-Greenow CH.

Discontinuation of epidural analgesia late in labour for

reducing the adverse delivery outcomes associated with

epidural analgesia. Cochrane Database Syst Review

2004;(4):CD004457. Crossref

53. Tuuli MG, Frey HA, Odibo AO, Macones GA, Cahill AG.

Immediate compared with delayed pushing in the second

stage of labor: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:660-8. Crossref

54. Lee AI, McCarthy RJ, Toledo P, Jones MJ, White N,

Wong CA. Epidural labor analgesia–fentanyl dose

and breastfeeding success: a randomized clinical trial.

Anesthesiology 2017;127:614-24. Crossref

55. Orbach-Zinger S, Landau R, Davis A, et al. The effect of

labor epidural analgesia on breastfeeding outcomes: a

prospective observational cohort study in a mixed-parity

cohort. Anesth Analg 2019;129:784-91. Crossref

56. Chan JJ, Dabas R, Han RN, Sng BL. Fever during labour

epidural analgesia. Trends in Anaesthesia and Crit Care

2018;20:21-5. Crossref

57. Higgins RD, Saade G, Polin RA, et al. Evaluation and

management of women and newborns with a maternal

diagnosis of chorioamnionitis: summary of a workshop.

Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:426-36. Crossref

58. Sultan P, David AL, Fernando R, Ackland GL. Inflammation

and epidural-related maternal fever: proposed mechanisms.

Anesth Analg 2016;122:1546-53. Crossref

59. Lim G, Facco FL, Nathan N, Waters JH, Wong CA,

Eltzschig HK. A review of the impact of obstetric anesthesia

on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Anesthesiology

2018;129:192-215. Crossref