Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE

Hong Kong College of Physicians Position

Statement and Recommendations on the

2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and 2018 European

Society of Cardiology/European Society of

Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of

Arterial Hypertension

KK Chan, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1; CC Szeto,FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)2; Christopher CM Lum, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)3; PW Ng, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)4; Alice PS Kong, MD, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)2; KP Lau, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)5; Jenny YY Leung, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)6; SL Lui, MD (HK), FHKAM (Medicine)7; KL Mo, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)1; Francis CK Mok, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)8; Vincent CT Mok, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)2; Bryan PY Yan, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)2; Philip KT Li, FHKCP, FHKAM (Medicine)2

1 Department of Medicine, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong

3 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Shatin Hospital, Hong Kong

4 Private Practice, Hong Kong

5 Department of Medicine, North District Hospital, Hong Kong

6 Department of Medicine, Ruttonjee Hospital, Hong Kong

7 Department of Medicine, Tung Wah Hospital, Hong Kong

8 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding authors: Dr KK Chan, Prof Philip KT Li (chankk5@ha.org.hk; philipli@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

The American College of Cardiology/American

Heart Association released guidelines for the

prevention, detection, evaluation, and management

of high blood pressure (BP) in adults in 2017. In

2018, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Society of Hypertension (ESH) published

new guidelines for the management of arterial

hypertension. Despite the many similarities between

these two guidelines, there are also major differences

in the guidelines in terms of diagnosis and treatment

of hypertension. A working group of the Hong

Kong College of Physicians (HKCP) convened

and conducted a focused discussion on important

issues of public interest, including classification of

BP, BP measurement, thresholds for initiation of

antihypertensive medications, BP treatment targets,

and treatment strategies. The HKCP concurs with

the 2018 ESC/ESH guideline on BP classification,

which defines hypertension as office systolic BP

≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg. The

HKCP also acknowledges the growing evidence of

home BP monitoring and ambulatory BP monitoring

in the diagnosis and monitoring of hypertension and

endorses the wider use of both methods. The HKCP

also supports the direction of a risk-based approach

for initiation of antihypertensive medications and

the specification of a treatment target range for

both systolic and diastolic BP with consideration of

different age-groups and specific disease subgroups.

Non-pharmacological interventions are crucial, both at the societal and individual patient levels.

The recent guideline publications provide good

opportunities to increase public awareness of

hypertension and encourage lifestyle modifications

among the local population.

Introduction

In 2017, the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) released a

guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation,

and management of high blood pressure (BP) in

adults.1 This guideline was a collaborative effort by

11 organisations that updated the JNC7 (Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention,

Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood

Pressure) in 2003.2 In 2018, the European Society of

Cardiology (ESC)/European Society of Hypertension

(ESH) published a new guideline for the management

of arterial hypertension.3 Both the European and

American guidelines provide comprehensive information for the clinical and public-health

practice communities on high BP management.

There are many similarities between these two

sets of guidelines: both emphasise the importance

of accurate BP measurement and encourage

out-of-office BP measurement for confirmation of

hypertension diagnosis. Both sets of guidelines also

recommend cardiovascular disease risk estimation

for risk stratification and a core strategy of

non-pharmacological lifestyle interventions and

drug treatment, including combination drug therapy.

Despite the many similarities between these two

guidelines, the guidelines also have major differences

in terms of diagnosis and treatment of hypertension.

Hypertension is prevalent in Hong Kong. In

a population health survey in 2014/15 conducted

by Department of Health,4 the prevalence of

hypertension (systolic BP [SBP] ≥140 mm Hg and/or

diastolic BP [DBP] ≥90 mm Hg) was 27.7% among

persons aged 15 to 84 years, with 47.5% of them

having been undiagnosed before the survey. The

prevalence of hypertension increased steadily with

age, from 4.5% among those aged 15 to 24 years to

64.8% among those aged 65 to 84 years.

A working group of the Hong Kong College

of Physicians (HKCP) convened and conducted a

focused discussion on important issues of public

interest pertaining to these two guidelines. This

document formulates the HKCP’s views on the

following issues: (1) classification of BP; (2) BP

measurement; (3) thresholds for initiation of

antihypertensive medications; (4) BP treatment

targets; and (5) treatment strategies.

Classification of blood pressure

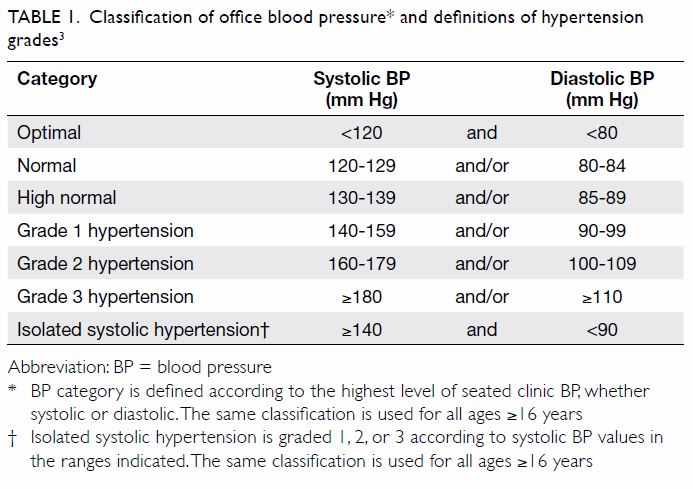

The 2018 ESC/ESH guideline defines hypertension

as office SBP ≥140 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥90 mm Hg

(Table 13). This definition remains unchanged from

the previous 2013 ESC/ESH guideline.5 However,

the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline contains a new BP

classification that proposes a lower threshold to

define hypertension (SBP ≥130 mm Hg and/or DBP

≥80 mm Hg). The same guideline defines normal

BP as <120/80 mm Hg and elevated BP as 120 to

129 mm Hg SBP and <80 mm Hg DBP.

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention

Trial is an important trial that significantly

influenced the recommendations of the 2017

ACC/AHA guidelines.6 The method used for office

BP measurement in the Systolic Blood Pressure

Intervention Trial was unattended automatic

measurement, in which automated multiple BP

readings in a doctor’s office are obtained with the

patient seated alone and unobserved. This method

has not been used in any previous randomised

controlled trials that provide an evidentiary basis

for the treatment of hypertension. The relationship

between conventional office BP measurement and unattended office BP measurement remains unclear,

but available evidence suggests that conventional

office SBP readings may be at least 5 to 15 mm Hg

higher.3

The 2017 ACC/AHA guideline’s definition

of hypertension is controversial. According to that

new definition, about 46% of adults in the US have

hypertension, as compared with about 32% under

the previous definition.1 This corresponds to an increase in the number of eligible patients requiring

treatment by more than 7 million in the US and more

than 55 million in China.7 The potential implications

for management of patients with hypertension are immense, both for individual patients as well society

and healthcare economics. The American College

of Physicians and the American Academy of Family

Physicians do not agree with this new definition of

hypertension.8

Other international guidelines, such as those

of the World Health Organization and International

Society of Hypertension,9 the Chinese Joint

Committee for Guideline Revision,10 the Japanese

Society of Hypertension,11 and Hypertension

Canada12 define hypertension as SBP ≥140 mm Hg

and/or DBP ≥90 mm Hg.

The HKCP concurs with the 2018 ESC/ESH

guideline on BP classification, which reflects the

BP-related cardiovascular risks and benefits of BP

reduction in clinical trials.

Blood pressure measurement

Both the European and American guidelines

strongly emphasise accurate BP measurement and

recording and consideration of readings in various

settings as needed. A description detailing the

steps of accurate BP measurement is provided (ie,

having the patient sit quietly for 5 minutes before

measurement, supporting the limb used to measure

BP, ensuring that the BP cuff is at heart level, and

using the correct cuff size). Out-of-office BP

measurements are recommended in patients with

suspected white coat hypertension, for confirmation

of the diagnosis of hypertension, and for titration of

BP-lowering medication, in conjunction with

telehealth counselling or clinical interventions.

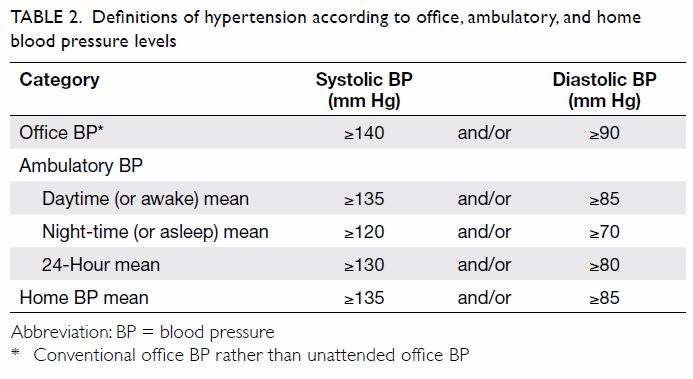

Out-of-office BP measurement refers to home

BP monitoring and ambulatory BP monitoring.

These two methods use different BP thresholds

to define high BP than office-based methods do.

The 2018 ESC/ESH statement’s best estimates for

corresponding clinic BP, home BP monitoring, and

ambulatory BP monitoring can be considered as a

guide (Table 2).

Table 2. Definitions of hypertension according to office, ambulatory, and home blood pressure levels

Although most randomised controlled trials have used clinic BP as the reference, the

HKCP acknowledges the growing body of evidence

surrounding the use of home and ambulatory BP

monitoring in the diagnosis and monitoring of

hypertension and endorses the wider use of both

methods.

Thresholds for initiation of

antihypertensive medications

Both the European and American guidelines adopt

a risk-based approach to treatment. Screening

for and management of other cardiovascular

disease risk factors common in hypertensive

patients is recommended. The European guideline

uses the Systematic COronary Risk Evaluation

system to estimate the 10-year risk of a first

fatal atherosclerotic event in relation to age, sex,

smoking habits, total cholesterol level, and SBP. It

is based on large, representative European cohort

datasets with correction factors for different

first-generation immigrants to Europe. Very high

risk, high risk, and moderate risk correspond to

calculated 10-year Systematic COronary Risk

Evaluation risk values of ≥10%, 5% to <10%, and

≥1% to <5%, respectively. Hypertensive patients

with documented cardiovascular disease, diabetes

mellitus, chronic kidney disease (stage 3-5), and very

high levels of individual risk factors (including grade

3 hypertension) are automatically considered to be

at high or very high risk.

The American guideline recommends using

the ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equations to estimate

the 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular

disease and to guide treatment in mild hypertension.

However, the ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equations

are validated only in the US adults aged 45 to

79 years in the absence of concurrent statin therapy.

The results cannot be generalised to other age and

ethnic groups, and there are no correction factors to

refine the risk calculations for Asian populations.

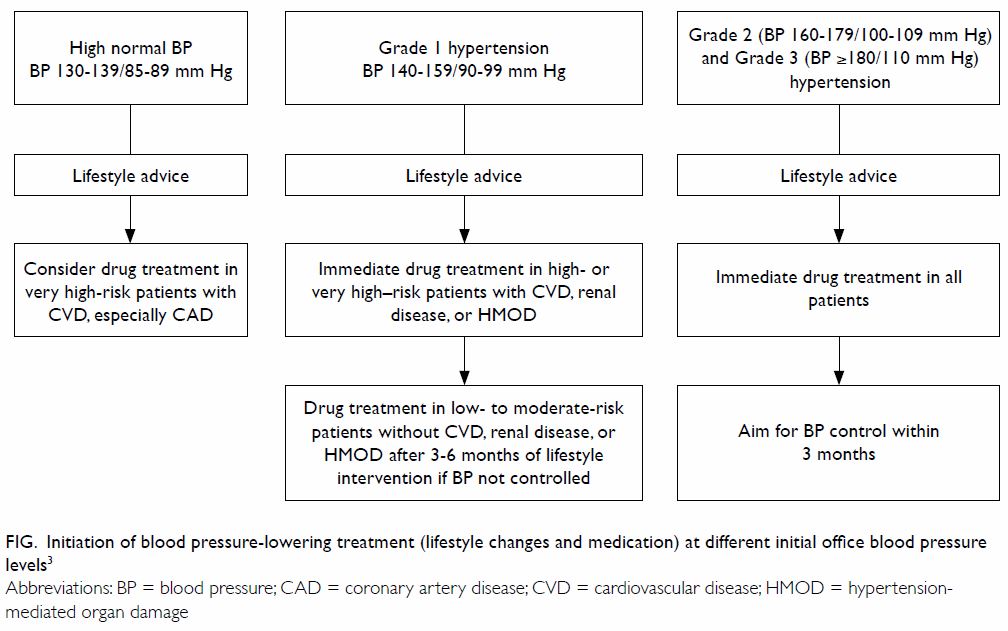

According to the 2018 ESC/ESH guideline,

patients with grade 2 and 3 hypertension should

be treated with BP-lowering drug treatment and

lifestyle interventions. In patents with grade 1

hypertension (BP 140-159/90-99 mm Hg) at high

risk of cardiovascular disease or with hypertension-mediated

organ damage, drug treatment should

also be initiated simultaneously with lifestyle

interventions. In low- to moderate-risk patients

with grade 1 hypertension, BP-lowering drug

treatment should be initiated after 3 to 6 months if

BP is not controlled by lifestyle interventions alone.

Drug treatment in adults with high normal BP

(130-139/85-89 mm Hg) should only be considered

in very high-risk situations with the presence

of established cardiovascular disease, especially

coronary artery disease (Fig3). In fit, older patients

with hypertension (aged ≥80 years), BP-lowering drug treatment and lifestyle interventions are

recommended when SBP ≥160 mm Hg and/or DBP

≥90 mm Hg.

Figure. Initiation of blood pressure-lowering treatment (lifestyle changes and medication) at different initial office blood pressure levels3

The HKCP supports the direction of a riskbased

approach to treatment decision making and

echoes the 2018 ESC/ESH approach. The HKCP

recommends that patients seek physicians’ advice

and that individualised treatment be provided after

a complete assessment of the patient’s clinical profile,

risk factors, and preferences.

Blood pressure treatment targets

The American guideline recommends lowering BP to

<130/80 mm Hg for adults, except in older patients

(aged ≥65 years, noninstitutionalised, ambulatory,

community-living adults), in whom the target is SBP

<130 mm Hg. This one-size-fits-all BP goal raises

much concern, especially for the elderly population.13

In contrast, the American College of Physicians

and the American Academy of Family Physicians

recommend pharmacological treatment to a target

of SBP <150 mm Hg in adults aged ≥60 years

who have persistently elevated SBP (≥150 mm Hg)

and to a target of SBP <140 mm Hg in selected

patients with high cardiovascular risk.8

The European guideline establishes target

ranges. The first objective is to lower BP to

<140/90 mm Hg in all patients, and provided that

treatment is well tolerated, treated BP values should

be targeted to ≤130/80 mm Hg in most patients.

In patients aged <65 years who are receiving BP-lowering drugs, it is recommended that SBP be

lowered to 120 to 129 mm Hg in most patients. If

the BP value reaches 120/70 mm Hg, a step-down

of drug treatment should be considered, with close

BP monitoring during follow-up. In older patients

(aged ≥65 years) and in patients with chronic kidney

disease, the SBP target should be less aggressive:

130 to 139 mm Hg. A DBP target range of 70 to

79 mm Hg is considered for all hypertensive patients,

independent of risk level and co-morbidities.

The HKCP concurs with the 2018 ESC/ESH

guideline in specifying target ranges for both SBP and

DBP, with consideration of different age-groups and

specific disease subgroups.

Treatment strategies

The European and American guidelines have much

in common in terms of treatment strategies.14 Both

recommend a similar array of non-pharmacological

lifestyle interventions and drug treatments as the

core strategy for BP reduction.

Non-pharmacological interventions are crucial

in the prevention and management of high BP, either

on their own or in combination with pharmacological

therapy. These include weight reduction, heart-healthy

diet, sodium reduction, physical exercise,

smoking cessation, and moderation in alcohol intake.

The core drug treatment is based on four major

classes: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,

angiotensin receptor blockers, calcium channel

blockers, and thiazide/thiazide-like diuretics. Beta blockers are used when there is a specific indication

(eg, heart failure, angina, post myocardial infarction,

or heart rate control). Both guidelines recommend

the initiation of treatment in most patients with a

single-pill combination containing two drugs to

improve adherence and BP control. It is reasonable

to use monotherapy in frail older patients and those

at low risk with mild hypertension.

The HKCP assigns major importance to

non-pharmacological interventions, both at the

societal and individual patient levels. The HKCP

sees the recent guideline publications as good

opportunities to increase public awareness about

hypertension and to encourage lifestyle modifications

among the local population.

The HKCP agrees with the 2018 ESC/ESH

guideline’s drug treatment algorithm and the

initiation of a two-drug combination in most patients.

Monotherapy is recommended in frail older patients

and those at low risk with mild hypertension.

Specific considerations for

geriatric patients

Older patients are characterised by clinical

heterogeneity. A multi-dimensional assessment

is required to assess the biological age of each

individual patient, as well as the risks and benefits of

tight BP control. For patients aged 65 to 79 years with

few co-morbidities who are biologically young, the

target SBP should be 130 to 139 mm Hg, provided

that a medication burden is acceptable. For patients

aged ≥80 years, or patients aged 65 to 79 years with

multiple co-morbidities who are biologically old

(ie, frail), the optimal BP targets are not yet defined

and have to be individualised. A treatment goal of

SBP of 130 to <150 mm Hg can be considered, as

suggested by other professional societies.10 15 Careful

monitoring for any adverse effects or tolerability

problems associated with BP-lowering treatment

is required in frail and dependent older adults.

Monotherapy rather than a single-pill combination

is the preferable initial pharmacotherapy according

to the 2018 ESC/ESH guideline.

Specific considerations for renal

patients

Patients with chronic kidney disease should be

considered as having high cardiovascular risk.

Adequate hypertension control is important for

reducing the rate of renal function deterioration as

well as cardiovascular protection. The BP targets

should be tailored according to age, tolerability,

and the level of proteinuria.16 For diabetic and

non-diabetic patients with albumin excretion rates

of <30 mg per 24 hours (or equivalent), the suggested

BP target is ≤140/90 mm Hg. For diabetic and

non-diabetic patients with urinary albumin excretion ≥30 mg per 24 hours (or equivalent), the suggested

BP target is ≤130/80 mm Hg. The available evidence

is inconclusive but does not prove that a BP target

of <130/80 mm Hg improves clinical outcomes

more than a target of <140/90 mm Hg in adults with

chronic kidney disease.16

Specific considerations for

diabetic patients

Diabetes in combination with hypertension

magnifies the risk of diabetes-related complications.

Control of BP reduces the risk of microvascular

(retinopathy and nephropathy) and macrovascular

(especially stroke) complications. A BP goal of below

130/80 mm Hg is appropriate for individuals with

diabetes, particularly those with established kidney,

eye, or cerebrovascular damage, provided that the

medication burden is acceptable.17

The authors represent the Hong Kong College of Physicians in

the following capacity:

President: Philip KT Li

Cardiology Board: KK Chan, Bryan PY Yan

Nephrology Board: SL Lui, CC Szeto

Geriatric Medicine Board: Christopher CM Lum, Francis CK Mok

Neurology Board: PW Ng, Vincent CT Mok

Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism Board: KP Lau, Jenny YY Leung

Advanced Internal Medicine Board: Alice PS Kong, KL Mo

President: Philip KT Li

Cardiology Board: KK Chan, Bryan PY Yan

Nephrology Board: SL Lui, CC Szeto

Geriatric Medicine Board: Christopher CM Lum, Francis CK Mok

Neurology Board: PW Ng, Vincent CT Mok

Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism Board: KP Lau, Jenny YY Leung

Advanced Internal Medicine Board: Alice PS Kong, KL Mo

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept of the manuscript,

acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting

of the article and critical revision for important intellectual

content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to

the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, BPY Yan was not involved in the

peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts

of interest.

Funding/support

This medical practice paper received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-forprofit

sectors.

References

1. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/

AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection,

Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in

Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical

Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:e127-248. Crossref

2. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report

of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure.

Hypertension 2003;42:1206-52. Crossref

3. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH

guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension.

Eur Heart J 2018;39:3021-104. Crossref

4. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Report of Population Health

Survey 2014/15. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/static/51256.html. Accessed 14 Jan 2020.

5. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC

guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the

Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension

of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of

the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J

2013;34:2159-219. Crossref

6. SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, et al.

A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure

control. N Eng J Med 2015;373:2103-16. Crossref

7. Khera R, Lu Y, Lu J, et al. Impact of 2017 ACC/AHA

guidelines on prevalence of hypertension and eligibility

for antihypertensive treatment in United States and

China: nationally representative cross sectional study. BMJ

2018;362:k2357. Crossref

8. Wilt TJ, Kansagara D, Qaseem A, Clinical Guidelines

Committee of the American College of Physicians.

Hypertension limbo: balancing benefits, harms and patient

preferences before we lower the bar on blood pressure.

Ann Intern Med 2018;168:369-70. Crossref

9. Whitworth JA, World Health Organization, International

Society of Hypertension Writing Group. 2003 World

Health Organization (WHO)/International Society

of Hypertension (ISH) statement on management of

hypertension. J Hypertens 2003;21:1983-92. Crossref

10. Joint Committee for Guideline Revision. 2018 Chinese guidelines for prevention and treatment of hypertension—a

report of the Revision Committee of Chinese Guidelines

for Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension. J Geriatr

Cardiol 2019;16:182-245.

11. Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, et al. The Japanese

Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management

of hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertens Res 2019;42:1235-

481. Crossref

12. Nerenberg KA, Zarnke KB, Leung AA, et al. Hypertension

Canada’s 2018 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment,

prevention and treatment of hypertension in adults and

children. Can J Cardiol 2018;34:506-25. Crossref

13. Bakris G, Sorrentino M. Redefining hypertension—assessing the new blood-pressure guidelines. N Eng J Med

2018;378:497-9. Crossref

14. Whelton PK, Williams B. The 2018 European Society

of Cardiology/European Society of Hypertension and

2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart

Association blood pressure guidelines: more similar than

different. JAMA 2018;320:1749-50. Crossref

15. Benetos A, Bulpitt CJ, Petrovic M, et al. An expert opinion

from the European Society of Hypertension–European

Union Geriatric Medicine Society Working Group on

management of hypertension in very old, frail subjects.

Hypertension 2016;67:820-5. Crossref

16. Tang SC, Wong AK, Mak SK. Clinical practice guidelines

for the provision of renal service in Hong Kong: general

nephrology. Nephrology (Carlton) 2019;24 Suppl 1:9-26. Crossref

17. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus

statement by the American Association of Clinical

Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology

on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management

algorithm—2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract

2020;26:107-29. Crossref