Hong Kong Med J 2020 Aug;26(4):311–7 | Epub 2 Jul 2020

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Factors associated with depression in people with

epilepsy: a retrospective case-control analysis

PH Ho, MB, BS1; William CY Leung, MRCP (UK)2; Ian YH Leung, MRCP (UK)2; Richard SK Chang, FHKCP2

1 Department of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Division of Neurology, Department of Medicine, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Richard SK Chang (changsk@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Purpose: This study investigated factors associated

with depression in people with epilepsy.

Methods: All adult patients attending our epilepsy

clinic in 2018 were screened for inclusion in this

study. Eligible patients were divided into case

and control groups, depending on the presence

of co-morbid depression. Depressive disorders

were diagnosed by a psychiatrist. Demographics

and clinical characteristics, including epilepsy

features and antiepileptic drug use, were compared

between groups. The factors contributing to onset of

depression after diagnosis of epilepsy were further

analysed by binomial logistic regression. Statistical

significance was set at P<0.05.

Results: Forty four patients with epilepsy who had

depression and 514 patients with epilepsy who did

not have depression were included in this study

(occurrence rate=7.9%). Female sex (P=0.005), older

age (P<0.001), temporal lobe epilepsy (P=0.01), and

higher number of antiepileptic drugs used (P=0.003)

were associated with depression in patients with

epilepsy. No differences were observed in other

epilepsy-related factors including aetiology, seizure

type, and laterality of epileptic focus. Binomial

logistic regression showed that female sex (P=0.01; odds ratio [OR]=3.56), drug-resistant epilepsy

(P<0.001; OR=4.79), and clonazepam use (P<0.001;

OR=14.41) were significantly positively associated

with risk of depression after epilepsy diagnosis,

whereas valproate use (P=0.03; OR=0.37) was

significantly negatively associated with risk of

depression.

Conclusion: Female sex, refractoriness, and

clonazepam use may be risk factors for depression

after epilepsy diagnosis. Valproate may protect

against depression in people with epilepsy. Better

understanding of clinical features may aid in medical

management or research studies regarding co-morbid

depression in people with epilepsy.

New knowledge added by this study

- This retrospective study investigated factors associated with depression in people with epilepsy, including a subgroup of patients who experienced depression onset after epilepsy diagnosis.

- Female sex, drug-resistant epilepsy, and clonazepam use were significantly positively associated with depression in people with epilepsy.

- Valproate use was significantly negatively associated with depression in people with epilepsy.

- Clinicians who treat patients with epilepsy should be aware of the potential for co-morbid depression, especially in patients with potential risk factors (eg, female sex, drug-resistant epilepsy, and temporal lobe epilepsy).

- Psychotropic properties of antiepileptic drugs should be carefully considered when choosing treatment agents for people with epilepsy; clonazepam may promote depression, whereas valproate may protect against depression.

Introduction

People with epilepsy are susceptible to psychiatric

disorders. Depression is arguably the most

common psychiatric co-morbidity, which affects

approximately 25% to 30% of people with epilepsy.1 2

Depression disorders increase the risk of suicide

among people with epilepsy.3 Notably, co-morbid

depression can greatly impact clinical outcomes and

quality of life for people with epilepsy.4

The relationship between epilepsy and

depression is more complex than simple

psychological stress related to chronic illness.

Structural and functional changes in the brain may

explain the underlying pathogenic mechanism.5 6

Furthermore, people with epilepsy who exhibit

co-morbid depression also demonstrate worse

seizure control, compared with people with epilepsy

who do not have depression.7 Suboptimal drug adherence and higher rates of adverse effects from

antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) have also been reported

among people with epilepsy who exhibit co-morbid

depression.8 9

As discussed in a recent systematic review,

many studies have attempted to evaluate the roles

of various epilepsy-related factors in the onset of

depression; however, most showed no associations

with depression or demonstrated inconsistent

results.10 The present study was performed to

investigate the relationships of clinical factors,

including use of AEDs, with depression in people

with epilepsy.

Methods

Patients and study design

This was a retrospective study. All adult patients,

aged ≥18 years, attending the epilepsy clinic of

Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong, from January

to December 2018, were screened for inclusion in

the study. Relevant data were retrieved from the

computerised medical records system. Diagnoses of

epilepsy were made or confirmed by a neurologist.

Patients with both epilepsy and depression were

included in the case group, while those with epilepsy

alone were included in the control group. Depression

was defined as the presence of depressive disorders

as described in the International Classification of

Diseases 10th Revision, diagnosed by a psychiatrist. Patients with intellectual disability were excluded

due to potential difficulties in determining diagnoses

of mood disorders in this group11; patients with other

psychiatric disorders were also excluded to avoid

confounding effects.

Collection of data

The following data were collected from medical

records: basic demographic characteristics, epilepsy

and depression details, and use of AEDs. Major

neurological and medical conditions that had been

present before the epilepsy and depression diagnoses

were also recorded. The categorisation of epilepsy

was performed in accordance with the International

League Against Epilepsy 2017 classification

scheme.12 Patients were determined to have drug-resistant

epilepsy when adequate trials of two

tolerated, appropriately chosen, and appropriately

used AED schedules (whether as monotherapies or

in combination) failed to achieve sustained seizure

freedom.13 Seizure freedom was defined as the

absence of seizures for 1 year. Seizure type, location,

and laterality of epileptic focus were determined

by seizure semiology, any previous neuroimaging

findings, and electroencephalography results.

Locations of epileptic foci were classified according

to cerebral lobes. Any AED used for >6 months was

recorded in this analysis; the maximum number of

AEDs used was also recorded. This study followed

the STROBE guidelines for study reporting.14

Statistical analysis

Clinical features were compared between the

groups with and without co-morbid depression.

The Chi squared test was used to detect statistically

significant differences in categorical data, and the

t test was used to detect any statistically significant

differences in continuous data. Sample size was

based on the existing patient number during the

study period; thus, no sample size calculations were

performed.

To investigate the effects of AEDs on

development of depression in people with epilepsy,

further analysis was performed regarding the

subgroup of patients in whom depression was

diagnosed after epilepsy onset. In particular, patients

were selected for whom depression diagnosis

occurred in the calendar year (or later) after the year

of epilepsy diagnosis. Relevant factors, particularly

use of AEDs, were analysed for their predictive value

in terms of depression development, using binomial

logistic regression. Variables were entered into the

regression model by forward selection, based on

likelihood ratios. Statistical analyses were carried

out using SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 25.0;

IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States). Statistical

significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

Forty four patients with epilepsy who had co-morbid

depression were selected as the case group, while

558 patients with epilepsy who did not exhibit

depression were selected as the control group; the

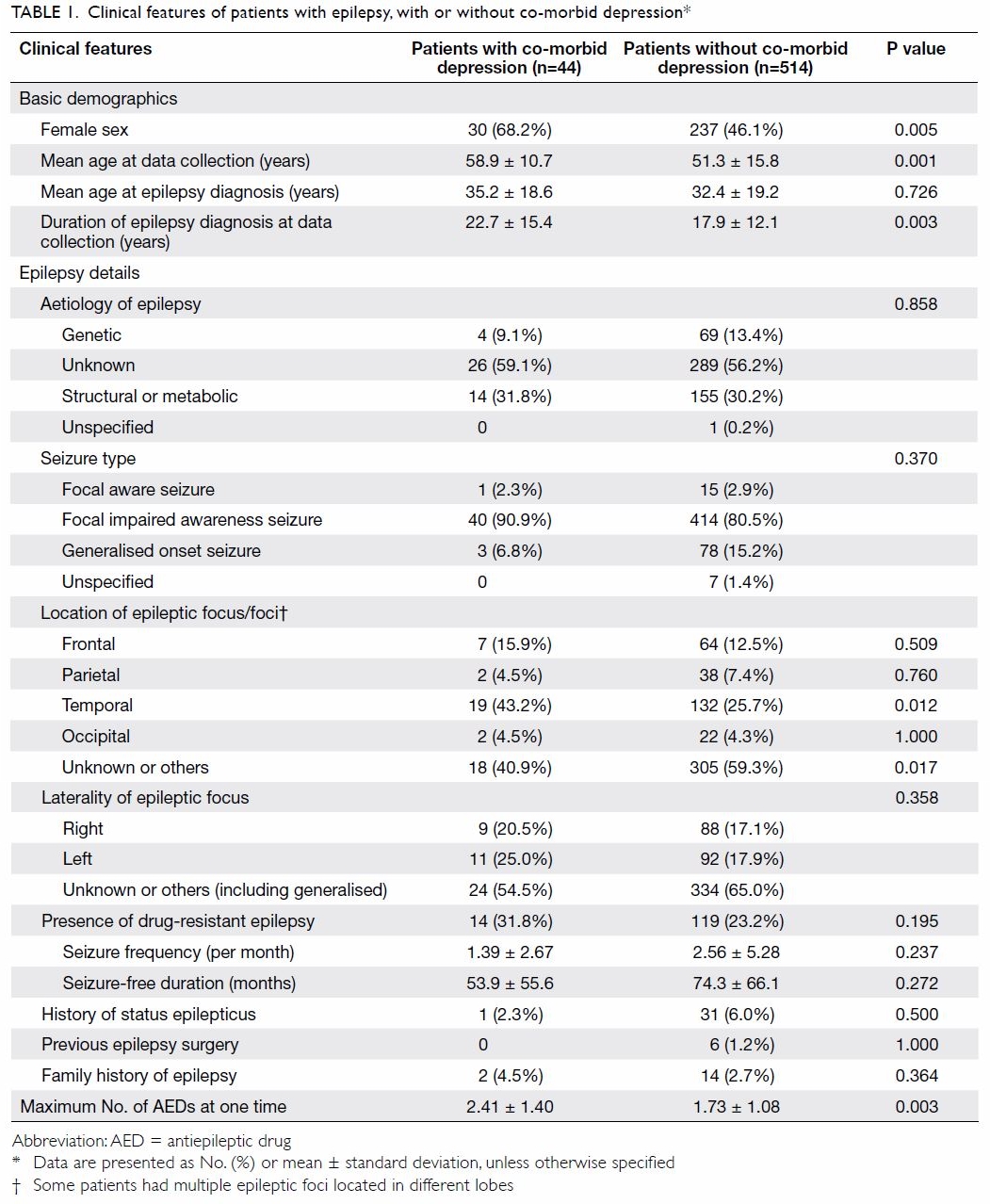

patient characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Among the patients with co-morbid depression,

32 (73%) experienced onset of epilepsy before the diagnosis of depression, while 12 (27%) had a

diagnosis of depression before the onset of epilepsy;

furthermore, 14 (32%) exhibited drug-resistant

epilepsy. Most patients with co-morbid depression

had a diagnosis of major depression (36/44, 82%); of

the remaining eight patients, one (2%) had dysthymia,

two (5%) had mixed anxiety and depressive disorder,

and five (11%) had a diagnosis of unspecified

depression. The mean age (±standard deviation)

at depression diagnosis was 46±13 years, while the mean age at epilepsy diagnosis was 35±19 years.

The mean duration between onset of epilepsy and

diagnosis of co-morbid depression was 13±13 years.

Most patients with epilepsy who had co-morbid

depression did not exhibit other major neurological

(36/44, 82%) or medical conditions (41/44, 93%). Of

the remaining eight patients with major neurological

conditions, six (14%) had stroke, one (2%) had

traumatic brain injury, and one (2%) had migraine.

Of the remaining three patients with major medical

conditions, two (5%) had malignancy and one (2%)

had rheumatoid arthritis. Notably, one patient had

both stroke and malignancy, while another patient

had both stroke and rheumatoid arthritis.

Comparison between case and control groups

Clinical features were compared between the case

and control groups (Table 1). Patients with depression

were older and included more women. A significantly

longer duration of epilepsy was observed in patients

with depression; however, the mean age at epilepsy

onset did not significantly differ between the groups.

Temporal lobe epilepsy was more common in

patients with depression; moreover, patients with

depression used a greater mean number of AEDs.

No differences were noted in other epilepsy-related

factors, including family history, drug-resistant

disease, seizure frequency, aetiology, seizure type,

or history of status epilepticus. Laterality in focal

epilepsy also showed no association with co-morbid

depression.

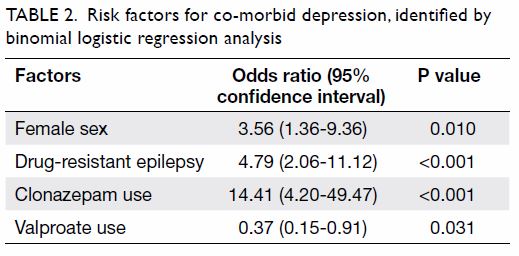

Subgroup analysis of patients in whom

depression was diagnosed after epilepsy onset

Relevant parameters were selectively included in

binomial logistic regression analysis to determine

risk factors for co-morbid depression (Table 2). The

relevant parameters depended on statistical results

in the whole group analysis and clinical judgement.

Parameters that reached statistically significance

in the whole group analysis were selected. Other

parameters considered as clinically important were

included as well. Only patients in whom depression

was diagnosed after epilepsy onset were included

in this analysis. Female sex, drug-resistant epilepsy, and clonazepam use were significantly positively

associated with a risk of co-morbid depression

among patients with epilepsy. In contrast, valproate

use was significantly negatively associated with a risk

of co-morbid depression.

Discussion

Depression is one of the most common psychiatric

co-morbidities among people with epilepsy. Our

study involving a cohort of people with epilepsy

revealed that 7.9% had depression; of these, 73%

had epilepsy onset before depression diagnosis.

This prevalence is much lower than the rate of

approximately 30% previously described in previous

studies of Western and Chinese populations17 16 17;

differences in study design may explain this

discrepancy. Previous studies were commonly

questionnaire or scale-based; generally, they used the

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Neurological

Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy, or

Patient Health Questionnaire nine-item depression

scale.18 19 20 Importantly, these different scales have

respective strengths and limitations.21 22 23 In our study,

the definition of depression was relatively stringent,

because it was confirmed by a psychiatrist. Patients

with co-existing psychiatric disorders (eg, psychotic

disorders, substance abuse, and personality

disorders) were deliberately excluded. Although

the psychiatric profile in our cohort was relatively

homogeneous because of the stringent criteria,

patients with relatively minor or occult depressive

symptoms might have been excluded. Importantly,

the low prevalence of depression may indicate that

this common affective disorder is often overlooked

by clinicians in our locality. Underdiagnosis of

psychiatric co-morbidities is a major problem

encountered by people with epilepsy.24 25 Awareness

of psychiatric co-morbidities, identified with the aid

of assessment scales, may improve the sensitivity of

diagnosis.

This study placed considerable emphasis

on the temporal relationship between epilepsy

and depression. A number of similar studies

used a cross-sectional design, which present a

methodological problem regarding the unclear

temporal relationship between epilepsy and

co-morbid depression.6 Extraction of data from

clinical records allows assessment of an individual

patient’s clinical features at different timepoints.

In the present study, only patients with depression

onset after epilepsy diagnosis were included in

logistic regression analysis, which enables clearer

assessment of the relationship between epilepsy and

co-morbid depression.

In our study, patients with epilepsy who

exhibited depression were predominantly women.

This finding is consistent with the results of a previous

systemic review.10 Female sex predominance has also been observed in studies of depression alone.26 27

In the present study, patients with depression were

older and had a longer duration of epilepsy diagnosis,

presumably because of accumulation bias. The mean

interval for development of depression was 13 years

after epilepsy onset; however, age at epilepsy onset

was not associated with development of depression.

It remains controversial whether younger epilepsy

onset age is related to a higher risk of subsequent

depression. Some studies have shown positive

associations, whereas others have not.28 29

Previous evidence suggested that focal

epilepsy, rather than generalised epilepsy, was

associated with co-morbid depression in people

with epilepsy.15 30 31 This finding was not observed

in our study; however, temporal lobe epilepsy

was significantly more prevalent in patients with

depression. The underlying pathogenic mechanism

may involve the close relationship of the temporal

lobe with the limbic system, which plays a key

role in emotional control. Frequent epileptic focus

discharge can lead to reduced blood flow and

metabolism in corresponding cerebral regions.5 32

Furthermore, temporal lobe epilepsy is associated

with hippocampal damage and atrophy, typically

comprising hippocampal sclerosis.33 Temporal lobe

hypometabolism and hippocampal volume loss have

also been implicated in depression.34 35 Finally, an

association of depression with epileptic foci in frontal

and left temporal lobes has also been reported,31 but

this phenomenon was not observed in our cohort.

In our study, drug-resistant epilepsy was

associated with depression in binomial logistic

regression analysis, but not when analysis was

performed using the Chi squared test. In this study,

patients included in analysis by the Chi squared test

had depression either before or after the diagnosis of

epilepsy. In contrast, the binomial logistic regression

model only included patients in whom depression

was diagnosed after epilepsy onset. Additionally,

the exact seizure frequency did not affect the risk

of depression in this study; conversely, seizure

frequency was associated with co-morbid depression

in a previous systemic review.10 This discrepancy may

be explained by differences in sample composition.

However, it remains unclear whether better epilepsy

control (ie, seizure frequency reduction) will alleviate

the risk of depression.

Use of AEDs also contributes to the onset

of mood disorder in people with epilepsy. This

study showed that clonazepam use was positively

associated with risk of depression in people with

epilepsy; conversely, valproate use was negatively

associated with risk of depression. The impact of

AEDs on psychiatric illness has been extensively

studied. Benzodiazepines, including clonazepam,

have been proposed to induce depression by

overinhibition of the GABAergic pathway.31 36 Valproate, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine are

examples of AEDs with positive psychotropic

effects, whereas benzodiazepine, levetiracetam,

phenobarbital, and topiramate exhibit negative

psychotropic effects.37 38 39 40

The findings of this study have a few important

implications for clinical practice. First, the

recognition of depression in people with epilepsy

can be challenging for clinicians, especially in a

busy out-patient clinic setting.24 The identification

of at-risk patients is essential for improving the

diagnostic yield of affective disorders among people

with epilepsy. Female sex, drug-resistant epilepsy,

and temporal lobe epilepsy may be associated with

co-morbid depression. Clinicians should be vigilant

in searching for depressive features in patients with

these characteristics during clinical consultation.

Second, the use of AEDs plays a role in

co-morbid depression in people with epilepsy.

Psychotropic properties of AEDs should be carefully

considered when choosing treatment agents for

people with epilepsy, especially for patients who

are at risk of depression (eg, women, patients with

drug-resistant epilepsy, and patients with temporal

lobe epilepsy). Clonazepam (ie, a benzodiazepine)

has been associated with depression onset in people

with epilepsy; in contrast, valproate may have a

protective effect against depression onset in people

with epilepsy. This could be due to the mood-stabilising

effect of valproate, which has led to its

use for treatment of patients with manic disorder.

Antiepileptic drugs can have a considerable impact

on quality of life in people with epilepsy, in addition

to their seizure control effects. The impact of newer-generation

AEDs requires further analysis, because

these drugs were inadequately represented among

the limited number of patients in the current study.

There were some limitations in this study.

First, there were inherent limitations due to the

retrospective nature of the analysis. In particular, the

information documented in medical records may not

be uniform and may be subject to recall bias. Second,

the diagnosis of depression in our study tended to

be stringent, because it relied on a psychiatrist’s

diagnosis, instead of more widely used assessment

tools (eg, depressive scales). However, this approach

may have led to underestimation regarding the

extent of depressive disorders among patients in this

cohort. Third, the AEDs were required to be used for

>6 months to be included in the analysis. However,

the durations, dosages, or serum drug levels of AEDs

were not considered, because they may have varied

during the course of epilepsy. Fourth, relatively few

socio-economic and psychological factors were

included in this analysis. Some previous studies

showed that these factors were associated with

co-morbid depression; however, they have been less

frequently investigated than other epilepsy-related factors (eg, employment, marital status, and stressful

life events).1 Further prospective studies that include

examinations of these psychosocial factors may

provide more complete information regarding

depression in people with epilepsy.

Conclusions

Depression is a common mood disorder in people

with epilepsy. This study showed that depression

tends to affect a subgroup of people with epilepsy who

exhibit specific demographic and epilepsy-related

factors. Notably, the use of AEDs may also influence

the risk of depression in people with epilepsy. This

study may contribute to better understanding of

clinical features, thereby aiding in future clinical

management or basic science studies regarding

co-morbid depression in people with epilepsy.

Author contributions

Concept or design: PH Ho.

Acquisition of data: PH Ho, RSK Chang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PH Ho, RSK Chang.

Drafting of the manuscript: PH Ho, RSK Chang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: PH Ho, RSK Chang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PH Ho, RSK Chang.

Drafting of the manuscript: PH Ho, RSK Chang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the

study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Declaration

This research was presented as a poster presentation titled

“Clinical features and predictors of depression in people with

epilepsy (PWE)” at the 33rd International Epilepsy Congress,

Bangkok, 22-26 June 2019.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Hospital Authority Hong Kong

West Cluster Institutional Review Board (Ref UW 19-742).

The need for informed consent was waived.

References

1. Hermann BP, Seidenberg M, Bell B. Psychiatric comorbidity

in chronic epilepsy: identification, consequences, and

treatment of major depression. Epilepsia 2000;41 Suppl

2:S31-41. Crossref

2. Asadi-Pooya AA, Kanemoto K, Kwon OY, et al. Depression

in people with epilepsy: how much do Asian colleagues

acknowledge it? Seizure 2018;57:45-9. Crossref

3. Kanner AM. Depression and epilepsy: a new perspective

on two closely related disorders. Epilepsy Curr 2006;6:141-

6. Crossref

4. Lehrner J, Kalchmayr R, Serles W, et al. Health-related

quality of life (HRQOL), activity of daily living (ADL)

and depressive mood disorder in temporal lobe epilepsy

patients. Seizure 1999;8:88-92. Crossref

5. Bromfield EB, Altshuler L, Leiderman DB, et al. Cerebral

metabolism and depression in patients with complex

partial seizures. Arch Neurol 1992;49:617-23. Crossref

6. Kanner AM, Schachter SC, Barry JJ, et al. Depression and

epilepsy: epidemiologic and neurobiologic perspectives

that may explain their high comorbid occurrence. Epilepsy

Behav 2012;24:156-68. Crossref

7. Hitiris N, Mohanraj R, Norrie J, Sills GJ, Brodie MJ.

Predictors of pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Epilepsy Res

2007;75:192-6. Crossref

8. Ettinger AB, Good MB, Manjunath R, Edward Faught R,

Bancroft T. The relationship of depression to antiepileptic

drug adherence and quality of life in epilepsy. Epilepsy

Behav 2014;36:138-43. Crossref

9. Cramer JA, Blum D, Reed M, Fanning K, Epilepsy Impact

Project Group. The influence of comorbid depression on

quality of life for people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav

2003;4:515-21. Crossref

10. Lacey CJ, Salzberg MR, D'Souza WJ. Risk factors for

depression in community-treated epilepsy: systematic

review. Epilepsy Behav 2015;43:1-7. Crossref

11. Walton C, Kerr M. Severe intellectual disability: systematic

review of the prevalence and nature of presentation

of unipolar depression. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil

2016;29:395-408. Crossref

12. Scheffer IE, Berkovic S, Capovilla G, et al. ILAE

classification of the epilepsies: position paper of the ILAE

Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia

2017;58:512-21. Crossref

13. Kwan P, Arzimanoglou A, Berg AT, et al. Definition of drug

resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task

Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies.

Epilepsia 2010;51:1069-77. Crossref

14. Equator Network. The Strengthening the Reporting

of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)

Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies.

Available from: http://www.equator-network.org.

Accessed 15 Nov 2019.

15. Chen K, Pan Y, Xu C, Wu W, Li X, Sun D. What are the

predictors of major depression in adult patients with

epilepsy? Epileptic Disord 2014;16:74-9. Crossref

16. Tellez-Zenteno JF, Patten SB, Jetté N, Williams J, Wiebe S.

Psychiatric comorbidity in epilepsy: a population-based

analysis. Epilepsia 2007;48:2336-44. Crossref

17. Kwong KL, Lam D, Tsui S, et al. Anxiety and depression in

adolescents with epilepsy. J Child Neurol 2016;31:203-10. Crossref

18. Alsaadi T, El Hammasi K, Shahrour TM, et al. Depression

and anxiety among patients with epilepsy and multiple

sclerosis: UAE comparative study. Behav Neurol

2015;2015:196373. Crossref

19. Azuma H, Akechi T. Effects of psychosocial functioning,

depression, seizure frequency, and employment on quality

of life in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2014;41:18-20. Crossref

20. Mohamed S, Gill JS, Tan CT. Quality of life of patients with

epilepsy in Malaysia. Asia Pac Psychiatry 2014;6:105-9. Crossref

21. Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Symonds P. Diagnostic validity

of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

in cancer and palliative settings: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2010;126:335-48. Crossref

22. Kim DH, Kim YS, Yang TW, Kwon OY. Optimal cutoff

score of the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory

for Epilepsy (NDDI-E) for detecting major depressive

disorder: a meta-analysis. Epilepsy Behav 2019;92:61-70. Crossref

23. Hartung TJ, Friedrich M, Johansen C, et al. The Hospital

Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the 9-item

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) as screening

instruments for depression in patients with cancer. Cancer

2017;123:4236-43. Crossref

24. O’Donoghue MF, Goodridge DM, Redhead K, Sander JW,

Duncan JS. Assessing the psychosocial consequences

of epilepsy: a community-based study. Br J Gen Pract

1999;49:211-4.

25. Boylan LS, Flint LA, Labovitz DL, Jackson SC, Starner K,

Devinsky O. Depression but not seizure frequency predicts

quality of life in treatment-resistant epilepsy. Neurology

2004;62:258-61. Crossref

26. Çakıcı M, Gökçe Ö, Babayiğit A, Çakıcı E, Eş A. Depression:

point-prevalence and risk factors in a North Cyprus

household adult cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry

2017;17:387. Crossref

27. Lam LC, Wong CS, Wang MJ, et al. Prevalence, psychosocial

correlates and service utilization of depressive and anxiety

disorders in Hong Kong: the Hong Kong Mental Morbidity

Survey (HKMMS). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol

2015;50:1379-88. Crossref

28. Kanner AM, Barry JJ. The impact of mood disorders in

neurological diseases: should neurologists be concerned?

Epilepsy Behav 2003;4 Suppl 3:S3-13. Crossref

29. Lacey CJ, Salzberg MR, D'Souza WJ. What factors

contribute to the risk of depression in epilepsy? Tasmanian

Epilepsy Register Mood Study (TERMS). Epilepsia

2016;57:516-22. Crossref

30. Kimiskidis VK, Triantafyllou NI, Kararizou E, et al. Depression and anxiety in epilepsy: the association with

demographic and seizure-related variables. Ann Gen

Psychiatry 2007;6:28. Crossref

31. Grabowska-Grzyb A, Jedrzejczak J, Nagańska E, Fiszer U.

Risk factors for depression in patients with epilepsy.

Epilepsy Behav 2006;8:411-7.Crossref

32. Victoroff JI, Benson F, Grafton ST, Engel J Jr,

Mazziotta JC. Depression in complex partial seizures.

Electroencephalography and cerebral metabolic correlates.

Arch Neurol 1994;51:155-63. Crossref

33. Kälviäinen R, Salmenperä T, Partanen K, Vainio P,

Riekkinen P, Pitkänen A. Recurrent seizures may cause

hippocampal damage in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology

1998;50:1377-82. Crossref

34. Hosokawa T, Momose T, Kasai K. Brain glucose

metabolism difference between bipolar and unipolar

mood disorders in depressed and euthymic states. Prog

Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2009;33:243-50. Crossref

35. Bremner JD, Narayan M, Anderson ER, Staib LH, Miller HL,

Charney DS. Hippocampal volume reduction in major

depression. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:115-8. Crossref

36. Luscher B, Shen Q, Sahir N. The GABAergic deficit

hypothesis of major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry

2011;16:383-406. Crossref

37. Tao K, Wang X. The comorbidity of epilepsy and

depression: diagnosis and treatment. Expert Rev Neurother

2016;16:1321-33. Crossref

38. Mula M, Agrawal N, Mustafa Z, et al. Self-reported

aggressiveness during treatment with levetiracetam

correlates with depression. Epilepsy Behav 2015;45:64-7. Crossref

39. Klufas A, Thompson D. Topiramate-induced depression.

Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1736.Crossref

40. Brent DA, Crumrine PK, Varma RR, Allan M, Allman C.

Phenobarbital treatment and major depressive disorder in

children with epilepsy. Pediatrics 1987;80:909-17.