Hong Kong Med J 2020 Jun;26(3):176–83 | Epub 1 Jun 2020

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

How are family doctors serving the Hong Kong

community during the COVID-19 outbreak? A survey of HKCFP members

Esther YT Yu, MB, BS, FHKAM (Family Medicine)1,2; Will LH Leung, FHKAM (Family Medicine), MScHSM (CUHK)1,3; Samuel YS Wong, MD, FHKAM (Family Medicine)1,4; Kiki SN Liu, BSc2; Eric YF Wan, PnD2,5; for the HKCFP Executive and

Research Committee

1 The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians, Hong Kong

2 Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

3 Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, Kowloon West Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong

4 The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

5 Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof Samuel YS Wong (yeungshanwong@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: This study evaluated the preparedness of family doctors during the early phase of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in Hong Kong.

Methods: All members of the Hong Kong College

of Family Physicians were invited to participate

in a cross-sectional online survey using a 20-item

questionnaire to collect information on practice

preparedness for the COVID-19 outbreak through

an email followed by a reminder SMS message

between 31 January 2020 and 3 February 2020.

Results: Of 1589 family doctors invited, 491 (31%)

participated in the survey, including 242 (49%) from

private sector. In all, 98% surveyed doctors continued

to provide clinical services during the survey period,

but reduced clinic service demands were observed

in 45% private practices and 24% public clinics.

Almost all wore masks during consultation and

washed hands between or before patient contact.

Significantly more private than public doctors

(80% vs 26%, P<0.001) experienced difficulties in

stocking personal protective equipment (PPE); more

public doctors used guidelines to manage suspected

patients. The main concern of the respondents was

PPE shortage. Respondents appealed for effective

public health interventions including border control,

quarantine measures, designated clinic setup, and public education.

Conclusion: Family doctors from public and private

sectors demonstrated preparedness to serve the

community from the early phase of the COVID-19

outbreak with heightened infection control measures

and use of guidelines. However, there is a need for

support from local health authorities to secure PPE

supply and institute public health interventions.

New knowledge added by this study

- The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in Hong Kong resulted in reduced primary care service demands and abrupt shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) among primary care clinics.

- The majority of surveyed Hong Kong family doctors consistently adopted facemask wearing and handwashing for infection control at their practice.

- Public health measures including border control, quarantine, and public education were advocated as important interventions to limit the spread of COVID-19.

- Family doctors in Hong Kong from both public and private sectors were willing and prepared to provide firstcontact clinical service to the community during the COVID-19 outbreak.

- Family doctors in Hong Kong needed better support from local health authorities on PPE supply, guided management of patients with COVID-19, greater availability of rapid diagnostic tests, and complementary public health interventions.

- Better coordination between public and private sectors is crucial, to include private family doctors as part of the overall health system strategy and emergency responses, because 70% of primary care consultations take place in the private sector in Hong Kong.

Introduction

Family doctors, serving as the first point of

professional contact for patients, are inevitably first

to identify probable cases of coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) among the many patients presenting

with respiratory symptoms each day.1 Family doctors

in Hong Kong have experience in dealing with the

severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic

in 20032 3 and the H1N1 pandemic in 2009.4 5

However, their preparedness in handling another

outbreak of a novel infectious disease has not been

explored. Furthermore, Hong Kong has a dual-track

healthcare system in which 70% of primary medical

care, especially acute episodic care, is provided in the

private sector where practice settings and resources

vary and differ from those of public clinics.6 7 8 Family

doctors play a crucial role in the community to

offer first contact and coordinated care for patients,

and their preparedness, perceptions, and attitudes

towards COVID-19 are particularly important to

inform future strategies for responding to epidemics. Hence, the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians

(HKCFP) conducted an online survey among its

members to evaluate preparedness and to identify

clinic-related challenges of private and public family

doctors who were providing primary care services

during the early phase of the evolving COVID-19

outbreak in Hong Kong.

Methods

All family doctors who are HKCFP members were

invited to complete an online survey. The structured

questionnaire (online supplementary Appendix 1)

comprised 20 questions. Twelve closed-ended

questions assessed the effects of the COVID-19

outbreak (at the time of the survey, the World

Health Organization had not announced it as a

pandemic) on clinical services and the preparedness

of the responding family doctors, such as changes in

infection control practice. An open-ended question

invited respondents to express their concerns

towards the COVID-19 outbreak and suggest

measures that would facilitate their clinical practice.

The last seven questions collected demographics of

the respondents. The survey questions were modified

from a previous survey for primary care doctors

in Hong Kong and Canada9 10 and pilot-tested by

a panel of experienced academic family doctors

and HKCFP Research and Executive Committee

members. Invitation e-mails and short message

service reminders were sent to target participants

between 31 January 2020 and 3 February 2020.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise

the characteristics of the respondents. Respondents

were stratified by their practice sector (ie, public

vs private). The differences in the effects of the

COVID-19 outbreak on the clinical practices, clinic

service, and infection control practices between

public and private family doctors were evaluated

by Pearson Chi squared test. Thematic analysis

was performed on the respondents’ free comments

and suggestions. The responses were reviewed

independently by two investigators and consolidated

into themes. Inconsistencies were resolved by

discussion between the two investigators to reach

consensus on a common theme. The consolidated

themes from the respondents’ suggestions and

concerns were further stratified by respondents’

practice sector using descriptive statistics.

All significance tests were two-tailed and those

with a P value of <0.05 were considered statistically

significant. The statistical analysis was executed by

Stata (Version 16.0; StataCorp LLC, College Station

[TX], US).

Since the survey was initially conducted to

examine the needs and preparedness of frontline

family doctors who are members of the HKCFP

during the early phase of COVID-19 outbreak in

Hong Kong, ethics approval was obtained from

the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics

Committee of The Chinese University of Hong Kong

subsequently for data analysis and presentation.

The Strengthening the Reporting of

Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)

checklist for cross-sectional studies was used in the

drafting of this article.11

Results

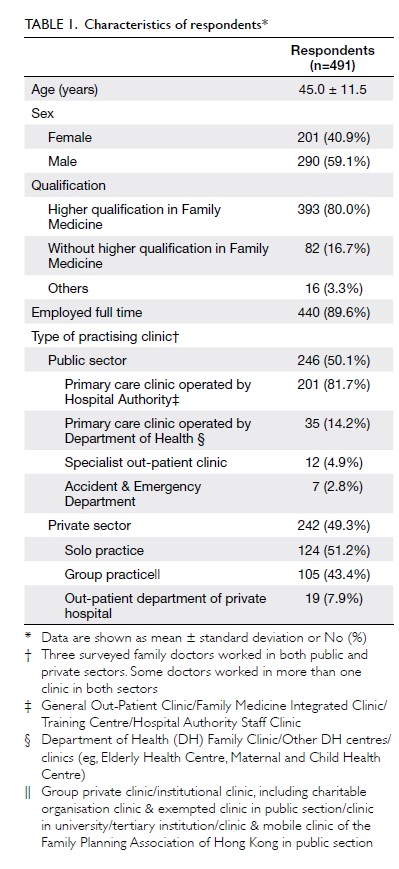

Of 1589 HKCFP members invited to complete

the survey, 491 (31%) provided a complete and

valid response (Table 1). Of the respondents, 393

(80%) had attained higher qualifications in Family

Medicine. Among the respondents, 236 (48%)

worked at public primary care clinics operated by

the Hospital Authority or Department of Health,

and 242 (49%) worked in the private sector, half of

whom were solo practitioners. The ratio of public to

private sector respondents was approximately 1:1.

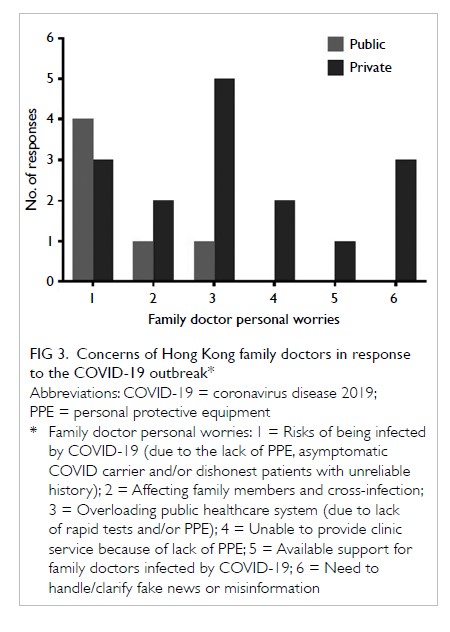

Effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on clinical

practices and regular clinic services

The vast majority of the respondents (n=482, 98%) continued to provide clinic services although most

of their clinic practices (n=428, 87%) had been

affected by the COVID-19 outbreak (Fig 1, online

supplementary Appendix 2). Significantly a higher

proportion of private than public family doctors

reported reduced clinic service demands during

this outbreak (n=111 [45%] vs n=60 [24%], P<0.001).

Half of the surveyed family doctors adjusted non-acute consultation services and/or reduced consultation time. As of 4 February 2020, over 140

patients with suspected severe acute respiratory

syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection

had been encountered by 70 (14%) surveyed family

doctors; one public family doctor reported

a patient who was subsequently confirmed to have

SARS-CoV-2 infection. Among the surveyed family

doctors, 310 (63%) perceived needs for more training

on how to deal with the COVID-19 outbreak. At time

of the survey, to assist clinical decision making for

diagnosing COVID-19, guidelines from the Centre

for Health Protection or the Hospital Authority

were used by public family doctors more frequently

than by private family doctors (n=143 [58%] vs

n=98 [40%], P<0.001). Conversely, 195 (80%) of

the surveyed private family doctors encountered

problems in stocking personal protective equipment

(PPE).

Figure 1. Effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on (a) clinical practices and (b) regular clinic service of family doctors in the public and private sectors in Hong Kong

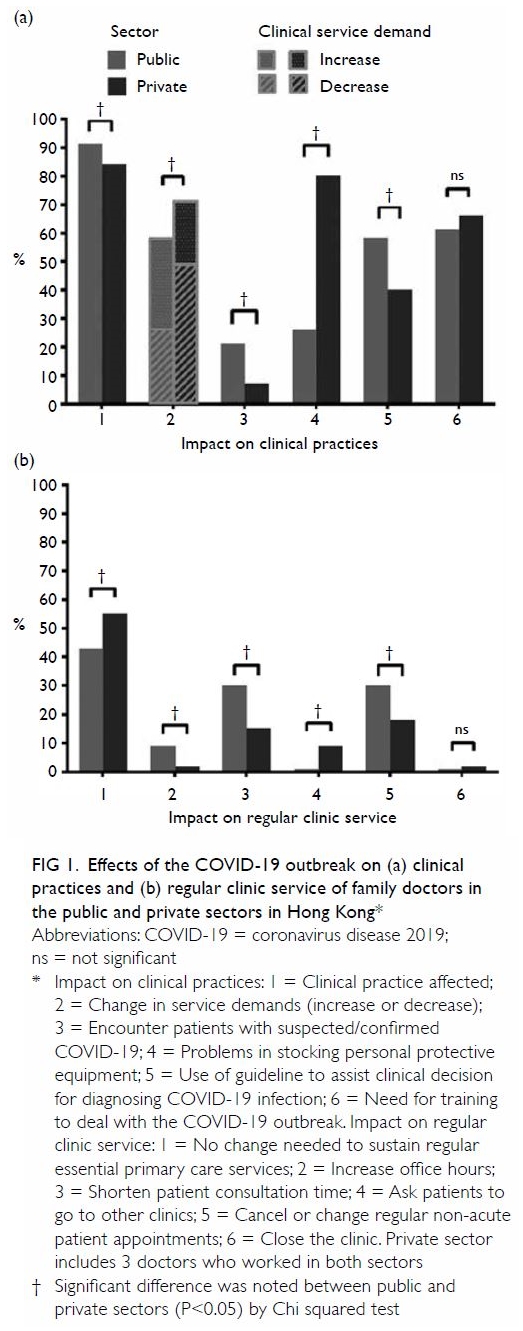

Changes in infection control practices in

response to the COVID-19 outbreak

Nearly all respondents wore masks during

consultations (n=490, 99%) and washed hands

between or before patient encounter (n=486, 99%)

[Fig 2 and Supplementary Appendix 2]. A greater

proportion of public than private family doctors

insisted patients wear masks during consultations

(n=210 [85%] vs n=165 [67%], P<0.001) and routinely

screened patients’ body temperatures (n=211 [86%]

vs n=183 [75%], P=0.002). In contrast, a greater

proportion of private than public family doctors

cleaned work surfaces with antiseptics at least once

a day (n=223 [91%] vs n=200 [81%], P=0.002) and

installed air purifiers (n=71 [29%] vs n=35 [14%],

P<0.001).

Figure 2. Clinic infection control practices of family doctors in the public and private sectors in Hong Kong in response to the COVID-19 outbreak

Suggested measures to respond to the

COVID-19 outbreak

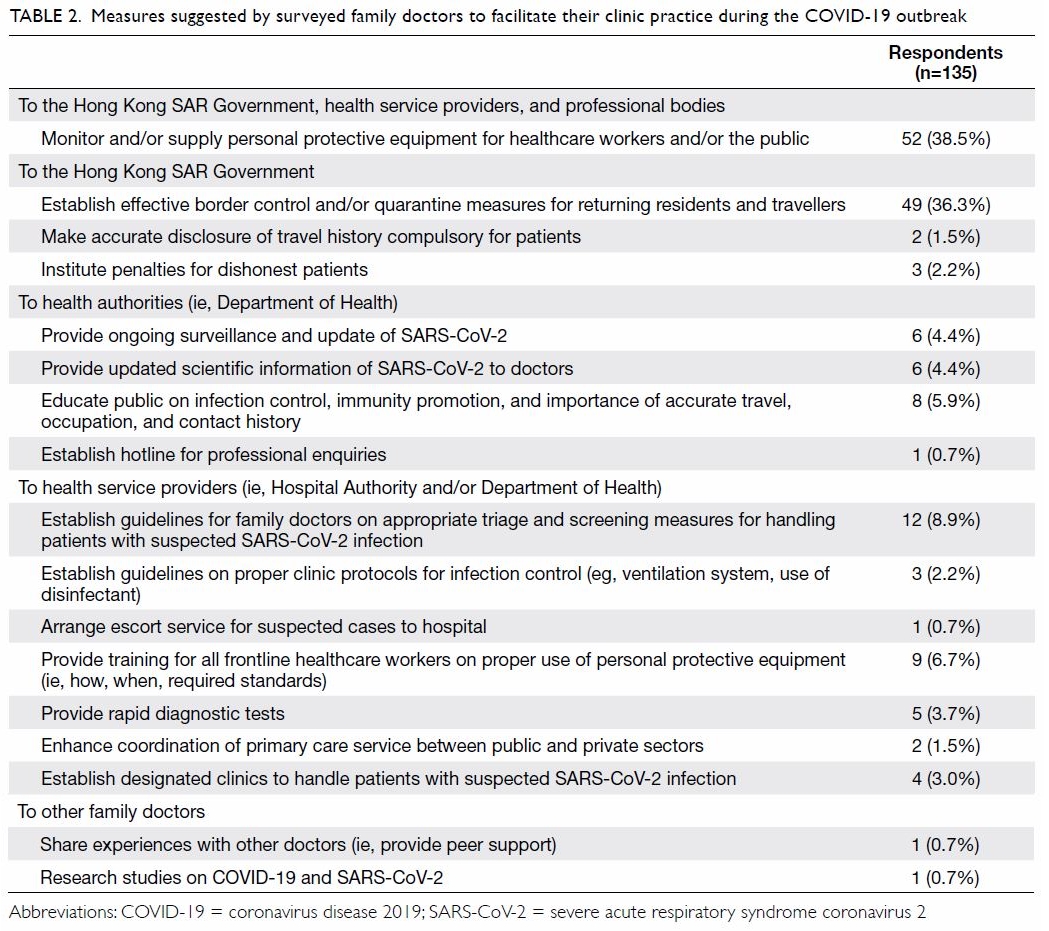

Of the respondents, 159 (32%) answered the open-ended

question, among which 135 (85%) suggested

measures to be instituted by government and/or

local health authorities to facilitate frontline family

doctors to respond to the COVID-19 outbreak

(Table 2). A significant proportion of respondents

(n=52, 39%) appealed to the government, health

service providers and/or professional bodies for

securing adequate supply of PPE, especially surgical

masks, for frontline healthcare workers as well as the

general public. There was a strong call (n=49, 36%)

for more effective public health policy to contain the

outbreak, such as border control and/or quarantine

measures for returning residents and travellers to

reduce imported cases. Two respondents (1.5%)

had expectations for better coordination between

the public and private sectors with respect to role

delineation and resource allocation, for example,

setting up a Primary Care Authority to maximise efficiency and effectiveness of scattered primary

healthcare delivery locally. Some family doctors (n=9,

7%) advocated for the introduction of designated

clinics and requested availability of rapid diagnostic

tests. A few respondents (n=8, 6%) stressed the

importance of public education on infection control

practice and reporting accurate travel and contact

history during consultation.

Table 2. Measures suggested by surveyed family doctors to facilitate their clinic practice during the COVID-19 outbreak

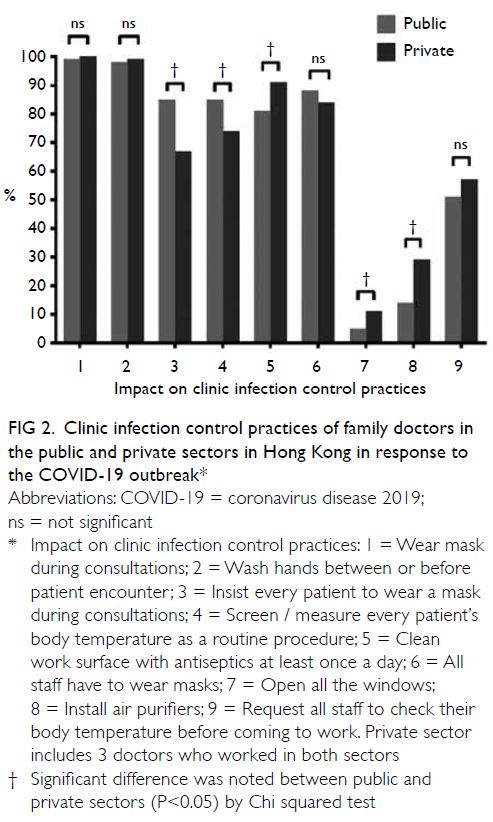

Concerns of Hong Kong family doctors in

response to the COVID-19 outbreak

Nineteen respondents (4%) expressed personal

concerns that were consolidated into six themes (Fig 3 and online supplementary Appendix 3). The major

concern was the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection,

as a result of the lack of PPE, consultation with an

asymptomatic patient with SARS-CoV-2 infection,

or dishonest patients with unreliable history. Owing

to the lack of rapid tests and/or PPE, two private

family doctors (11%) worried that they would be

unable to provide clinic services, resulting in public

healthcare system overload. Three respondents

(16%) raised concerns about the need to handle

and/or clarify “fake news” (ie, misinformation).

Discussion

The vast majority of surveyed family doctors were

committed to discharging their duties in the early

phase of the COVID-19 outbreak despite clinical

uncertainties, psychological distress arising from

infectious risk to self and family, and corresponding

significant effects on clinical services. Only 2% of

the surveyed private family doctors had closed their

clinics, compared with 8% during the SARS epidemic

in 2003.9 These figures were also much lower than

reported absenteeism rates of healthcare workers

during influenza pandemics.12 13 14 In the 2009 H1N1

pandemic in 2009, 59% of local primary care doctors

reported higher demands in clinical services.4 In

contrast, in the present study, 25% of public family

doctors and 45% of private family doctors reported

reductions in clinical service demand. Different from

an influenza outbreak when primary care doctors are

tasked with providing confirmatory diagnostic tests

and antiviral treatment, rapid diagnostic tests were not readily accessible in the primary care setting at

time of our survey, and treatments for COVID-19 were available only in hospital settings. Patients

with highly probable SARS-CoV-2 infection were

sent directly to hospital isolation wards for further

management. Patients suspecting themselves to have

SARS-CoV-2 infection presented in large numbers

to emergency departments instead of primary care

clinics. Local citizens were also strongly encouraged

to practise social distancing, especially avoiding areas

of high contact risk, including clinics.15 Patients with

other non-urgent health needs might opt to delay their

clinic visits. Nevertheless, family doctors encountered

probable SARS-CoV-2 infection, especially patients

with milder, non-specific respiratory symptoms

and with less clear travel and/or contact history.

Thus, family doctors needed to remain vigilant in

identifying suspected cases in the community during

this period, while providing continuing care to other

patients with unrelated medical conditions, mental

health support for patients affected by the outbreak

and educating healthy patients.

Although the mode of transmission of

COVID-19 was not clearly understood in the early phase of outbreak, almost all surveyed family doctors

readily adopted standard droplet and contact

precautions, including wearing facemasks during

consultation and washing hands before and/or

between seeing patients as recommended by the

Centre for Health Protection of Hong Kong.16

Wearing facemask during consultation became

a common practice among family doctors in

Hong Kong since the global outbreak of SARS.4 9 17

Conversely, hand hygiene practices of family doctors

were less consistent and varied between 45% before

the H1N1 influenza epidemic4 to 70% during SARS

in 2003.9 In the present survey, 99% of family

doctors reported washing their hands before patient

encounters during the current outbreak, which has

been proven more effective than facemask wearing

alone in limiting the transmission of respiratory

infections.18 19 The practice of other recommended

infection control measures differed between public

and private family doctors, reflecting practical

challenges in their implementation. A particular

infection control challenge for local small-sized

clinics would be the required isolation of patients

with suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection, where an

extra single isolation room with or without negative

pressure, or even a designated isolation area >1 m

from the rest of the waiting area, was often

unavailable.16 To protect other patients from possible

cross-infection in clinics, respondents adjusted non-nonacute

patient appointments, shortened consultation

times to avoid crowding of patients in the clinic,

or divert patients to other clinics. Despite the

variations, these infection control measures might

be contributory to the zero-infection rate observed

among primary care providers in Hong Kong at the

time of the survey.

Many respondents considered public health

policies and interventions in response to the

COVID-19 outbreak to be important. There has

been an escalation of infection control responses

to the COVID-19 outbreak, especially wearing

of facemasks, in the healthcare20 and community

settings.21 Consequently, an acute shortage of

facemasks was experienced by respondents, similar

to the situation observed in the US.22 Echoing the

viewpoints of Australian general practitioners

towards influenza pandemic management, family

doctors from Hong Kong also considered that

government and health authorities should be

responsible for ensuring steady supply of PPE to

frontline healthcare workers and/or the public.23

A few surveyed family doctors commented that

they would cease to provide clinical service if PPE

became unavailable, owing to the high infection

risk. Moreover, a large proportion of respondents

advocated for border controls and quarantine

measures to limit cross-border transmission.24

Subsequently, border controls and mandatory

quarantine were implemented on people arriving

from mainland China in early February 2020,25 and

extended to travellers from most regions around the

globe in March 2020.26 These measures may have

contributed to the relatively slow rise in the number

of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Hong Kong.

Some private family doctors requested the

introduction of designated fever clinics for the

public, so that high-risk patients presenting with

fever and/or respiratory symptoms could be diverted

to a designated location and managed appropriately.

Such arrangements would be particularly important

for protecting the many small private clinics

which lack the capacity to properly isolate high-risk

patients. Designated clinics were successfully

implemented in Hong Kong during the 2009 H1N1

pandemic5 and in China and the US during the

current COVID-19 outbreak.1 22 Unfortunately,

local citizens opposed these clinics owing to a fear

of COVID-19 transmission in the neighbourhood.

Instead, designated doctors were assigned to attend

high-risk or febrile patients in certain public primary

care clinics. However, the arrangement was not clear

to the public nor frontline private family doctors and

symptomatic patients continued to seek care from

private family doctors. Despite repeated calls for

coordinated care or clear role delineation of family

doctors between public and private sectors at times

of outbreak, this has still not been achieved.5 9

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study had two key strengths. First, our survey

was conducted in the early phase of the COVID-19

outbreak, thus the survey rapidly captured the early

effects of an emerging outbreak on primary care

services and reflected the clinic preparedness and

needs of frontline family doctors in Hong Kong.

Second, our study covered family doctors from both

public and private sectors, allowing for comparison

between the two sectors. Possible service gaps in the

current dual-track primary healthcare system could

be readily identified to inform policy makers.

A major limitation of this study was the low

response rate, attributable to the relatively short

survey period. Although our response rate (31%) was

lower than previous similar surveys among family

doctors in Hong Kong during SARS (75%) and H1N1

pandemic (42%), the crude response rate was higher

(n=491, vs 137 and 126, respectively). However, our

respondents included only approximately 10% of the

doctors listed in the Primary Care Directory.27 Also,

only HKCFP members and fellows were targeted

in this survey. Hence, the sample might not be

representative of all primary care physicians in Hong

Kong. Lastly, as an observational study, reporting

bias existed.

Conclusion

Family doctors from both public and private sectors

in Hong Kong reported willingness and preparedness

to provide primary, continuous, and whole-person

care to the community from the early phase of the

COVID-19 outbreak. Despite limitations in clinic

physical settings and potential for PPE shortages,

most family doctors adopted standard precautions

and effectively protected themselves and the public

from cross-infection. Nevertheless, there is an obvious

need for health authorities to improve role delineation

and coordination between private and public primary

care services and to provide relevant support during

an outbreak, so that family doctors can continue to

play their various roles in the community under the

current dual-track primary healthcare system.

Author contributions

Concept or design: SYS Wong, EYT Yu, WLH Leung.

Acquisition of data: SYS Wong, EYT Yu, WLH Leung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: SYS Wong, EYT Yu, WLH Leung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank The Hong Kong College of Family

Physicians (HKCFP) Research and Executive Committee

members who have contributed to the design of questionnaire

and review of the draft, including Dr Angus Chan, Dr David

Chao, Dr Catherine Chen, Dr Lap-kin Chiang, Dr Billy Chiu,

Dr Cecilia Fan, Dr Ho-lim Lau, Dr Jun Liang, Dr Shuk-yun

Leung, Dr Lorna Ventura Ng, Professor Martin Wong, and

Dr William Wong; and Miss Erica So, Miss Crystal Yung, and

Miss Angel Fung who provided administrative support for the

study. We would also like to thank all the participating family

doctors who responded promptly to this survey.

Declaration

This research has not been presented in any academic

conference or published previously. Part of the findings from

the survey was disseminated through a local press release on

10 March 2020.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Survey and Behavioural

Research Ethics Committee of The Chinese University of

Hong Kong (Ref SBRE-19-578).

References

1. Li DK, Zhu S. Contributions and challenges of general

practitioners in China fighting against the novel coronavirus

crisis. Fam Med Community Health 2020;8:e000361. Crossref

2. Zhong NS, Zheng BJ, Li YM, et al. Epidemiology and

cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in

Guangdong, People’s Republic of China, in February, 2003.

Lancet 2003;362:1353-8. Crossref

3. Tsang KW, Ho PL, Ooi GC, et al. A cluster of cases of

severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J

Med 2003;348:1977-85. Crossref

4. Wong SY, Kung K, Wong MC, et al. Primary care

physicians’ response to pandemic influenza in Hong Kong:

a mixed quantitative and qualitative study. Int J Infect Dis

2012;16:e687-91. Crossref

5. Lee A, Chuh AA. Facing the threat of influenza pandemic—roles of and implications to general practitioners. BMC

Public Health 2010;10:661. Crossref

6. Lee A. Seamless health care for chronic diseases in a dual

health care system: managed care and the role of family

physicians. J Manag Med 1998;12:398-405. Crossref

7. Working Party on Primary Health Care. Health for all, the

way ahead: Report of the Working Party on primary health

care. Hong Kong: Government Printer; 1990.

8. Wun YT, Lee A, Chan KK. Morbidity pattern in private and

public sectors of family medicine/general practice in a dual

health care system. Hong Kong Practitioner 1998;20:3-15. Crossref

9. Wong WC, Lee A, Tsang KK, Wong SY. How did general

practitioners protect themselves, their family, and staff

during the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong? J Epidemiol

Community Health 2004;58:180-5. Crossref

10. Wong SY, Wong W, Jaakkimainen L, Bondy S, Tsang

KK, Lee A. Primary care physicians in Hong Kong and

Canada—how did their practices differ during the SARS epidemic? Fam Pract 2005;22:361-6. Crossref

11. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC,

Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening

the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

(STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting

observational studies. Lancet 2007;370:1453-7. Crossref

12. Balicer RD, Omer SB, Barnett DJ, Everly GS, Jr. Local

public health workers’ perceptions toward responding to

an influenza pandemic. BMC Public Health 2006;6:99. Crossref

13. Ehrenstein BP, Hanses F, Salzberger B. Influenza pandemic

and professional duty: family or patients first? A survey of

hospital employees. BMC Public Health 2006;6:311. Crossref

14. Damery S, Wilson S, Draper H, et al. Will the NHS

continue to function in an influenza pandemic? A survey of

healthcare workers in the West Midlands, UK. BMC Public

Health 2009;9:142. Crossref

15. Fung CS, Yu EY, Guo VY, et al. Development of a Health

Empowerment Programme to improve the health of

working poor families: protocol for a prospective cohort

study in Hong Kong. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010015. Crossref

16. Ashton LM, Hutchesson MJ, Rollo ME, Morgan PJ, Collins

CE. Motivators and barriers to engaging in healthy eating

and physical activity. Am J Mens Health 2017;11:330-

43. Crossref

17. Wong CK, Yip BH, Mercer S, et al. Effect of facemasks on

empathy and relational continuity: a randomised controlled

trial in primary care. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:200. Crossref

18. Cowling BJ, Chan KH, Fang VJ, et al. Facemasks and hand

hygiene to prevent influenza transmission in households:

a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:437-

46. Crossref

19. Aiello AE, Murray GF, Perez V, et al. Mask use, hand

hygiene, and seasonal influenza-like illness among young

adults: a randomized intervention trial. J Infect Dis

2010;201:491-8. Crossref

20. Cheng VC, Wong SC, Chen JH, et al. Escalating infection

control response to the rapidly evolving epidemiology of

the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) due to SARS-CoV-2 in Hong Kong. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol

2020;41:493-8. Crossref

21. Leung CC, Lam TH, Cheng KK. Mass masking in the COVID-19 epidemic: people need guidance. Lancet

2020;395:945. Crossref

22. Kamerow D. Covid-19: Don’t forget the impact on US

family physicians. BMJ 2020;368:m1260.Crossref

23. Shaw KA, Chilcott A, Hansen E, Winzenberg T. The GP’s

response to pandemic influenza: a qualitative study. Fam

Pract 2006;23:267-72. Crossref

24. Jefferson T, Foxlee R, Del Mar C, et al. Physical interventions

to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses:

systematic review. BMJ 2008;336:77-80. Crossref

25. Viner R, Macfarlane A. Health promotion. BMJ

2005;330:527-9. Crossref

26. Magnussen CG, Koskinen J, Chen W, et al. Pediatric

metabolic syndrome predicts adulthood metabolic

syndrome, subclinical atherosclerosis, and type 2 diabetes

mellitus but is no better than body mass index alone: the

Bogalusa Heart Study and the Cardiovascular Risk in

Young Finns Study. Circulation 2010;122:1604-11. Crossref

27. Hong Kong SAR Government. Primary Care Directory.

Available from: https://apps.pcdirectory.gov.hk. Accessed

15 Mar 2020.