© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

CASE REPORT

Secondary organising pneumonia complicating

acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by

severe influenza A: a case report

Alwin WT Yeung, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)1; Judianna SY Yu, MB, BS, MRCP1; Richard WC Wong, FHKCPath, FHKAM (Pathology)2

1 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Ruttonjee Hospital, Wan Chai, Hong Kong

2 Department of Clinical Pathology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Alwin WT Yeung (yeungwt@ha.org.hk)

Case report

A 69-year-old man with a history of diabetes mellitus

and benign prostatic hypertrophy was admitted

to our medical unit with a 1-week history of fever,

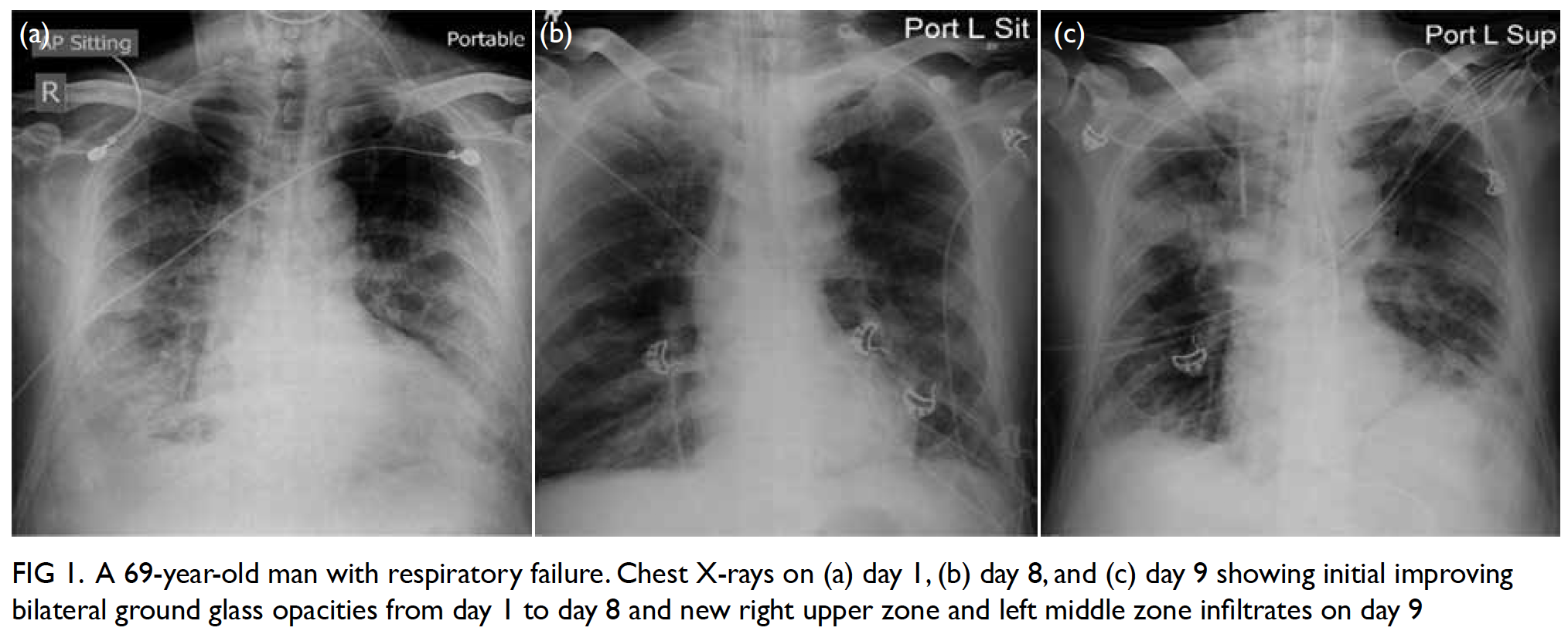

runny nose, and shortness of breath. Chest X-ray

revealed bilateral diffuse ground glass opacities in

both lung fields. The patient had type 1 respiratory

failure and required non-invasive positive pressure

ventilation to maintain oxygenation. The patient was

given ceftriaxone 1 g every 12 hours, and doxycycline

100 mg and oseltamivir 75 mg twice daily. He was

transferred to the intensive care unit and intubated

due to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome

(ARDS). The patient’s nasopharyngeal swab was

tested by polymerase chain reaction and the result

was positive for influenza A virus H1 RNA. His

clinical course was further complicated by septic

acute kidney injury that necessitated continuous

venovenous haemofiltration. His lungs gradually

improved with supportive measures including prone

ventilation and muscle paralysis for 48 hours. The

fractional oxygenation requirement improved from

1.0 to 0.4 between day 1 and day 8 of admission and

chest X-ray showed improving aeration of both lungs.

Unfortunately, his ventilatory requirement

deteriorated again from day 9 onwards, with chest

X-ray showing new right upper zone and left middle

zone infiltrates (Fig 1). Repeat microbiological

investigation results were negative except for

Candida albicans and Candida species in the

endotracheal culture. Antibiotics were upgraded to

meropenem 500 mg every 8 hours. High-resolution

computed tomography of the thorax on day 14

showed patchy consolidation with air bronchogram

and ground glass opacities in both lungs, more

prominent in the right upper lobe, right lower

lobe, and left lower lobe, and mild bilateral pleural

effusions.

Figure 1. A 69-year-old man with respiratory failure. Chest X-rays on (a) day 1, (b) day 8, and (c) day 9 showing initial improving bilateral ground glass opacities from day 1 to day 8 and new right upper zone and left middle zone infiltrates on day 9

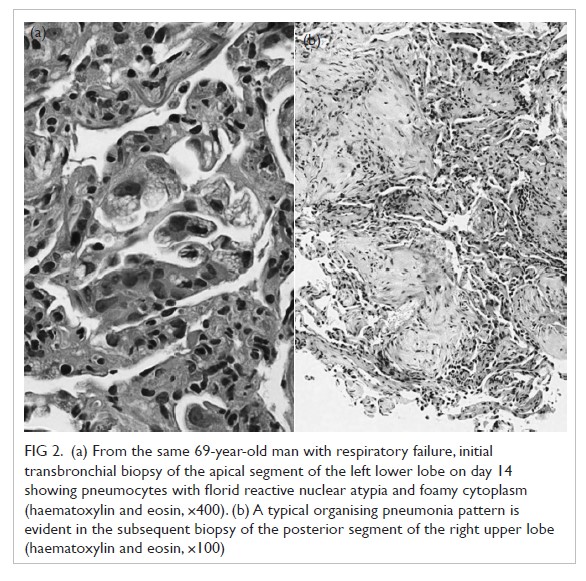

Bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy

of the apical segment of the left lower lobe was

performed uneventfully. Histological examination

of the biopsy specimen revealed alveolar lining

partially composed of cuboidal cells with foamy

cytoplasm, a variable degree of nuclear enlargement

and pleomorphism, and prominent nucleoli. The

histology could be suggestive of adenocarcinoma

with appropriate clinical settings. In view of the

unusual clinical course, it was decided to repeat transbronchial biopsies at different sites, namely at

the left lower lobe apical segment again on day 18

and the right upper lobe posterior segment on day

19. Both histological specimens revealed a pattern

compatible with organising pneumonia (OP) [Fig 2].

Intravenous hydrocortisone 100 mg every 8 hours

and subsequently enteral prednisolone 40 mg

daily were prescribed, and surgical tracheostomy

performed in view of the prolonged mechanical

ventilation.

Figure 2. (a) From the same 69-year-old man with respiratory failure, initial transbronchial biopsy of the apical segment of the left lower lobe on day 14 showing pneumocytes with florid reactive nuclear atypia and foamy cytoplasm (haematoxylin and eosin, ×400). (b) A typical organising pneumonia pattern is evident in the subsequent biopsy of the posterior segment of the right upper lobe (haematoxylin and eosin, ×100)

The patient showed dramatic improvement

with steroid treatment. He was weaned off mechanical

ventilatory support and renal replacement therapy

and discharged from the intensive care unit on

day 22. He underwent rehabilitation in a general

ward and was weaned off tracheostomy and

supplementary oxygen. Serial chest X-rays showed

resolution of both lung consolidations with minimal

residual fibrotic scarring.

Discussion

In general, H1 influenza infection causes mild upper

respiratory tract symptoms. A minority of patients

present with ARDS secondary to viral pneumonia

with or without bacterial co-infection. Apart from

neuraminidase inhibitors such as oseltamivir,

management is mostly supportive. This includes

protective lung ventilation and a conservative fluid

management strategy. In moderate to severe ARDS

with partial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired

oxygen ratio <150 mm Hg, 48 hours of muscle paralysis, prone ventilation, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may be required.

The definition of ARDS includes acute onset

within 1 week, bilateral radiological opacities not

explained by pleural effusion or lung collapse,

respiratory failure not explained by heart failure,

or fluid overload with partial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen ratio <300 mm Hg under

a positive end-expiratory pressure of at least 5 cm

H2O. Typically, patients with ARDS exhibit diffuse

alveolar damage in histological specimens, divided

into an acute exudative phase shortly after the

pulmonary insult, followed by an organising phase,

with or without a final fibrotic phase. However, a

continuum and overlapping features exist, especially

late in the first week or if the patient has encountered

repeat pulmonary insults. The acute exudative phase

is characterised by hyaline membranes that gradually

disappear in the subsequent organising phase. The

organising phase is characterised by interstitial

fibrosis and pronounced type 2 pneumocyte

hyperplasia. Cytological atypia may be quite

pronounced and can be confused with malignancy,

as in our case.1 Subsequently, diffuse alveolar damage

will gradually resolve although some may progress

to a fibrotic phase with continued interstitial fibrosis

and compromises lung function.

Other histological patterns can present in

patients with ARDS, including OP and acute fibrinous

OP. In acute fibrinous OP, the alveolar spaces are

filled with organising fibrin balls instead of hyaline

membranes, whereas in OP, patchy accumulation of

intra-alveolar organising fibroblastic tissue primarily

centred around bronchioles is present.2

Organising pneumonia, acute fibrinous

OP, and diffuse alveolar damage are histological

manifestations arising from a broad range of

pulmonary insults. Temporal and regional

heterogeneity of the pulmonary parenchymal

alterations may result in diverse or mixed patterns

upon lung biopsy sampling. Corticosteroids remain

the first-line therapy in OP. Around two thirds

of patients with OP respond to treatment with

corticosteroids. However, the role of corticosteroids

in diffuse alveolar damage remains controversial.

The steroid response of acute fibrinous OP is

intermediate, between that of diffuse alveolar

damage and OP.3

To the best of our knowledge, few cases of post-influenza OP have been reported in the literature.4 5

Most were influenza A infection and patients

usually presented with refractory respiratory failure,

incomplete recovery, or new radiological infiltrate

after initial improvement. Most cases responded

well to corticosteroid therapy.

The present case demonstrates that OP can

complicate influenza-related ARDS. Physicians

should be aware of this possibility: timely confirmation by histological proof, exclusion of superimposed nosocomial pneumonia, and

initiation of corticosteroid therapy after balancing

the risks and benefits may result in a more favourable

outcome in the disease trajectory.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept of study, acquisition and analysis of data, drafting of the manuscript, and had

critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual

content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to

the study, approved the final version for publication, and take

responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This case report received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient verbally agreed publication of this

anonymous case report.

References

1. Butnor KJ. Avoiding underdiagnosis, overdiagnosis, and misdiagnosis of lung carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med

2008;132:1118-32.

2. Beasley MB. The pathologist's approach to acute lung injury. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010;134:719-27.

3. Bihari S, Bailey M, Bersten AD. Steroids in ARDS: to be or not to be. Intensive Care Med 2016;42:931-3. Crossref

4. Cornejo R, Llanos O, Fernández C, et al. Organizing pneumonia in patients with severe respiratory failure due

to novel A (H1N1) influenza. BMJ Case Rep 2010; 2010. pii:

bcr0220102708.Crossref

5. Asai N, Yokoi T, Nishiyama N, et al. Secondary organizing pneumonia following viral pneumonia caused by severe

influenza B: a case report and literature reviews. BMC

Infect Dis 2017;17:572. Crossref