Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Dec;25(6):491.e1-2

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PICTORIAL MEDICINE

Giant perivascular spaces: an uncommon cause of

obstructive hydrocephalus

MH So, MB, BS FRCR; WK Lo, FRCR, FHKAM (Radiology)

Department of Diagnostic and Interventional

Radiology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Yaumatei, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr MH So (manhon.so@gmail.com)

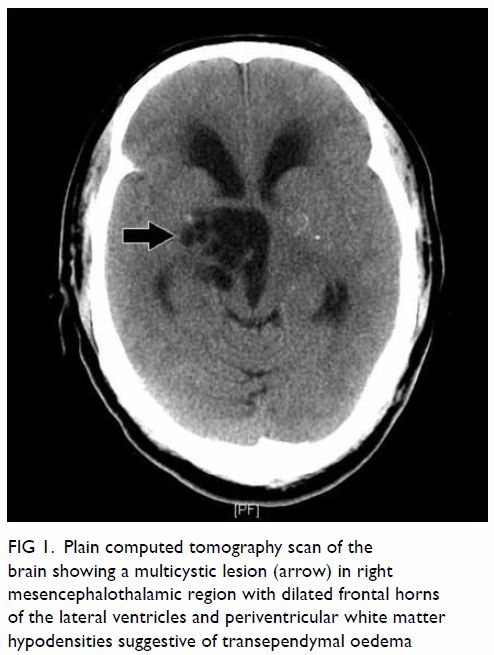

A 55-year-old man with good past health presented

to the emergency department with unsteady gait for 6 months with recent

mild left-sided weakness. Urgent computed tomography (CT) scan of the

brain showed a multiseptated cystic lesion in the right

mesencephalothalamic region with pressure effect on the third ventricle

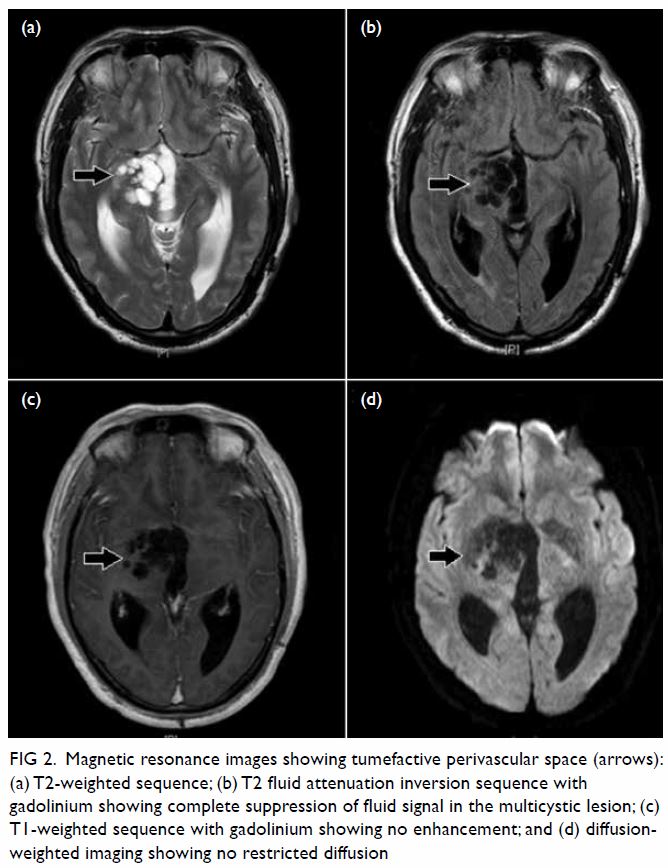

causing obstructive hydrocephalus (Fig 1). Urgent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

(Fig 2) of the lesion showed no post-gadolinium

enhancement, no restricted diffusion, complete suppression of the cystic

areas on T2 fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence and no

abnormal parenchymal signal intensities compared with normal brain

parenchyma. These imaging findings are consistent with tumefactive

perivascular space. Invasive biopsy and surgical excision were avoided,

and the patient underwent surgery for ventricular drain insertion.

Figure 1. Plain computed tomography scan of the brain showing a multicystic lesion (arrow) in right mesencephalothalamic region with dilated frontal horns of the lateral ventricles and periventricular white matter hypodensities suggestive of transependymal oedema

Figure 2. Magnetic resonance images showing tumefactive perivascular space (arrows): (a) T2-weighted sequence; (b) T2 fluid attenuation inversion sequence with gadolinium showing complete suppression of fluid signal in the multicystic lesion; (c) T1-weighted sequence with gadolinium showing no enhancement; and (d) diffusionweighted imaging showing no restricted diffusion

Dilated perivascular spaces (PVSs) in the brain are

interstitial fluid-filled structures lined by pia-mater that have

accompanying patent penetrating arteries within, most commonly seen along

the lenticulostriate arteries.1

They can be unilocular or multilocular and may have a radial pattern along

the course of the penetrating arteries. The PVSs occur across all

age-groups and are more frequent and larger with advancing age. The cause

of dilated PVS remains unknown though numerous theories have been

postulated including increased permeability of arterial wall and

obstruction/disturbance of interstitial fluid drainage/flow. Dilated PVSs

may be associated with microvascular diseases, trauma, non-vascular

dementia, multiple sclerosis, and the mucopolysaccharidoses.

Rarely PVSs are markedly expanded and are termed

tumefactive or giant PVSs. Some authors define tumefactive PVSs as those

>1.5 cm. Tumefactive PVSs are most commonly located in

mesencephalothalamic region.2 They

are also seen in cerebral white matter and in the cerebellar dentate

nuclei. They can exhibit mass effect and cause obstructive hydrocephalus

when occurring in the mesencephalothalamic region as in our case. The MRI

signal intensities of typical PVSs should follow cerebrospinal fluid in

all sequences including FLAIR imaging with no post-gadolinium enhancement.

There is no restricted diffusion as the compartments are communicating.

Tumefactive PVSs in cerebral white matter may have perilesional abnormal

T2 and FLAIR hyperintensities in up to 50% of cases. The mass effect of

the tumefactive PVS may cause chronic ischaemic change in adjacent white

matter.3 Histopathological results

typically show a pial-lined cyst with no evidence of neoplasm or

infection.

Differential diagnoses include cystic infarction,

tumour, and infection.4 Cystic

infarctions assume a slit-like or ovoid shape whereas PVSs are more

rounded or linear. The cystic content of tumours is usually not isointense

to cerebrospinal fluid on MRI. Solid components are often present, which

may enhance after contrast and are surrounded by oedema. Parasitic

infections have a range of appearances on CT or MRI scans with contrast

enhancement and oedema during the active phase and calcifications in the

quiescent phase.

Asymptomatic tumefactive PVSs can be managed by

follow-up imaging for stability in size. Spontaneous regression of

tumefactive PVSs without surgical intervention is rare. Tumefactive PVSs

with mass effect and obstructive hydrocephalus can be treated surgically

with ventriculostomy, cyst fenestration, ventriculoperitoneal shunting, or

cystoperitoneal shunting. When the appearance is typical, surgical biopsy

or excision should be avoided.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept, acquisition

and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and revision for

important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of

interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patient was treated in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided informed consent for all

procedures.

References

1. AI Abdulsalam H, Alatar AA, Elwatidy S.

Giant tumefactive perivascular spaces: a case report and literature

review. World Neurosurg 2018;112:201-4. Crossref

2. Choh NA, Shaheen F, Robbani I, Singh M,

Gojwari T. Tumefactive Virchow–Robin spaces: a rare cause of obstructive

hydrocephalus. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2014;17:345-6. Crossref

3. Salzman KL, Osborn AG, House P, et al.

Giant tumefactive perivascular spaces. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:298-

305.

4. Kwee RM, Kwee TC. Virchow-Robin spaces

at MR imaging. Radiographics 2007;27:1071-86. Crossref