Hong Kong Med J 2019 Dec;25(6):473–82 | Epub 4 Dec 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REVIEW ARTICLE CME

Assessment and diagnosis of dementia: a review for

primary healthcare professionals

K Lam, FRCP (Edin), FHKAM (Medicine)1;

Windy SY Chan, MClinPharm, DHSc2; James KH Luk, FHKCP, FHKAM

(Medicine)3; Angela YM Leung, PhD, FHKAN (Geron)4

1 Cheshire Home (Shatin), Hospital

Authority, Hong Kong

2 School of Health Sciences, Caritas

Institute of Higher Education, Hong Kong

3 Department of Medicine, Fung Yiu King

Hospital, Hong Kong

4 Centre for Gerontological Nursing, The

Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Angela YM Leung (angela.ym.leung@polyu.edu.hk)

Abstract

Dementia is one of the most costly,

disabling diseases associated with ageing, yet it remains underdiagnosed

in primary care. In this article, we present the comprehensive approach

illustrated with a classical case for diagnosing dementia which can be

applied by healthcare professionals in primary care. This diagnostic

approach includes history taking and physical examination, cognitive

testing, informant interviews, neuropsychological testing, neuroimaging,

and the utility of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. For the differential

diagnosis of cognitive impairment, the differences and similarities

among normal ageing, mild cognitive impairment, depression, and delirium

are highlighted. As primary care physicians are playing an increasingly

prominent role in the caring of elderly patients in an ageing

population, their role in the diagnosis of dementia should be

strengthened in order to provide a quality care for patients with

dementia.

Introduction

Among people aged >65 years, the global

prevalence of dementia has been estimated as 5%,1

with an overall prevalence of 3.9% in Asia.2

The prevalence increases with ageing, with more than one third of people

aged >85 years having dementia.1

In 2015, it was estimated that 46.8 million people lived with dementia

worldwide, with those numbers expected to almost double every 20 years

until reaching 131.5 million in 2050.3

In China, the burden of dementia is increasing much more rapidly than

previously assumed by the international health community.4 Earlier and more accurate detection of dementia is

critical because it allows patients to plan their future care while they

still have the capacity to make important decisions.5 Only through receiving a diagnosis can a person with

dementia obtain access to cognitive and pharmacological therapies.

However, dementia is underdiagnosed in primary care. Evidence from a

primary care-based screening and diagnosis programme in the United States

revealed that only 19% of patients with a confirmed dementia diagnosis had

been checked for dementia during routine medical care.6

A population-based study showed that approximately

20% of family informants failed to recognise memory problems in elderly

subjects who were found to have dementia on a standardised examination.7 A United Kingdom study showed that

earlier diagnosis may also ease caregiver concerns.8 Planning by families of elderly patients is most

effective when dementia is diagnosed early in the course of the illness.

Accurate diagnosis with subtyping is the prerequisite for providing

optimal therapies specific to different dementia diagnoses. In addition,

reversible causes of cognitive impairment, eg, depression, should be

looked for.9

This article reviews recent approaches in dementia

diagnosis and discusses their applications by healthcare professionals,

particularly those working in the primary care setting.

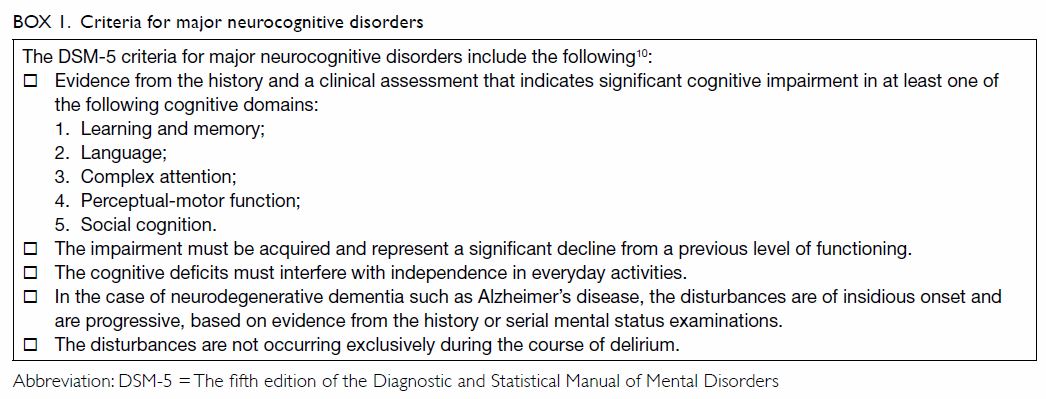

Definition of dementia

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) provides a common framework for the

diagnosis of neurocognitive disorders, including dementia, which is named

‘major neurocognitive disorder’ in this edition.10

11 It serves as a common

linguistic framework to deal with neurocognitive disorders, thus promoting

efficient communication among clinicians and researchers.11 The criteria for major neurocognitive disorders are

summarised in Box 1.

The major limitation of the DSM-5 is that it

requires intellectual deficits to be sufficiently severe to impair social

or occupational functioning. Therefore, it necessarily draws an arbitrary

line between dementia and the lack thereof. In clinical settings, patients

usually pass through stages of intellectual decline, including cognitive

deficits thought to occur with normal ageing, mild cognitive impairment

(MCI), and early dementia.12

Differential diagnosis of cognitive impairment

Accurately diagnosing dementia remains a challenge

for healthcare professionals, as there is no definitive diagnostic test to

identify it.

Does Mrs Wong have dementia?

Mrs Wong, aged 83 years, has a history of

hypertension and diabetes mellitus. She lives with her daughter’s family

and her activities of daily living are independent. In the past half year,

her family members have noticed that Mrs Wong sometimes misses

appointments with friends and her favourite Chinese music classes. Mrs

Wong denies physical discomfort but cannot recall the details of her

appointments. Her daughter helps by marking every appointment on a

calendar to remind her. Mrs Wong is unable to handle her own banking and

has become lost on the street when she goes shopping on her own. She

occasionally becomes irritable when she encounters difficulties in

recalling memories.

Not all patients with memory loss complaints have

dementia. There are four common conditions that primary care doctors need

to differentiate from dementia.

Cognitive changes with normal ageing

The normal cognitive decline associated with ageing

consists primarily of mild changes in memory and the rate of information

processing and does not usually affect daily functioning. Normative data

from cross-sectional studies examining neuropsychological performance

demonstrate that the ability to perform new learning or acquisition

declines with age, whereas cued recall remains stable.12 13 14 Agerelated declines are not inevitable, and when they

do occur, careful evaluation for underlying age-related diseases is

warranted.

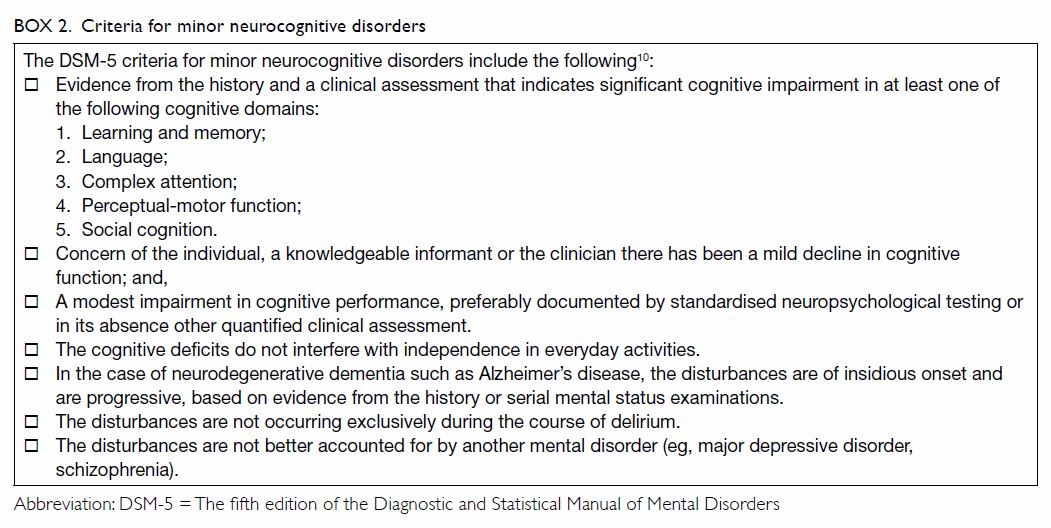

Mild cognitive impairment

Mild cognitive impairment is defined by the

presence of memory difficulty and objective memory impairment but

preserved ability to function in daily life.

While cognitive changes with normal age refer to

normal age-associated memory and cognitive changes in older adults

compared with young normal adults, MCI refers to abnormal changes in

cognitive functioning, and the criteria include a measurable cognitive

deficit in at least one domain.15

16 17

This condition is considered to be a transitional

stage between normal ageing and dementia. There is no pharmacological

treatment for MCI at this time. Studies have shown that subjects with MCI

followed for up to 4 years have an annual conversion rate ranging from 6%

to 25%, but not all of those with MCI evolve to dementia.18 Subjects with MCI may fluctuate between different

trajectories of MCI, including normal cognition, MCI, and dementia.19 Progression from ‘normal to MCI’ or ‘normal to MCI to

dementia’ is not always linear: subjects who develop MCI and later return

to normal may develop dementia later.20

Longitudinal follow-up of MCI subjects is indicated to avoid missing a

diagnosis of dementia conversion.20

The criteria for minor neurocognitive disorders are summarised in Box

2.

Depression

Memory impairment is commonly associated with major

depression in elderly people, and it can cause pseudo-dementia syndrome.

Patients with depression usually present with persistent sadness, loss of

interest in their usual activities, sleep and appetite disturbances, or

feelings of worthlessness or guilt.10

The most commonly used clinical screening tool for depression is the

Geriatric Depression Scale.21

Patients with depression may have signs of psychomotor slowing and apply

little effort to testing, while those with dementia often try hard but

respond with incorrect answers. Antidepressants may improve patients’ mood

and cognitive symptoms. However, dementia can sometimes co-exist with

depression, and treatments may be required for both.

Delirium

Delirium, or acute confusional state, is another

common condition in elderly people. It is usually acute or subacute in

onset and is associated with sensory clouding; patients have fluctuations

in their consciousness level and have difficulty maintaining attention and

concentration.22 Delirium is

associated with a variety of systemic illnesses, infections, and toxic and

metabolic disturbances.

Delirium is uncommon among community-dwelling

elderly people. The Canadian Study of Health and Aging found that the

prevalence of delirium is <0.5% among elderly people living outside of

acute care.23 Nevertheless,

hospitalised elderly patients are more prone to delirium. Studies have

shown that approximately 11% to 25% of hospitalised older patients have

delirium upon admission, and an additional 29% to 31% of older patients

admitted without delirium will develop it.24

25 Elderly patients have a

decreased level of brain reserve, which makes them more prone to

decompensation during acute stress and the development of delirium.

It is important to recognise that patients with

dementia are at increased risk of delirium and that delirium and dementia

may coexist. The most commonly used instrument for screening and

identifying delirium is the Confusion Assessment Method.26 The updated standard diagnostic criteria for delirium

are stipulated in the DSM-5.

Aetiology of dementia

Once a patient is diagnosed with dementia, it is

important to determine the underlying aetiologies. These include various

neurodegenerative diseases as well as metabolic and toxic causes. Among

them, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia in

elderly individuals, accounting for 60% to 80% of all cases, followed by

vascular dementia (VaD), which accounts for about 20%.4 27 The

distribution of dementia varies across geographical locations and cultural

and socio-economic differences. In the Chinese population, the median

proportions of AD and VaD in all forms of dementia were around 70% and

24%, respectively; other forms constituted 7.5%.4

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is among the most common forms of

degenerative dementia, accounting for 4.2% of all diagnosed dementia cases

in the community.28 Frontotemporal

dementia (FTD), Parkinson-plus syndromes, alcohol-related dementia,

chronic traumatic encephalopathy, and other central nervous system

illnesses are uncommon causes and are responsible for the majority of the

remaining chronic dementia cases.12

Common subtypes of dementia

Alzheimer’s disease is usually a disease of ageing,

and its incidence increases exponentially with age >65 years. The onset

and progress of AD are insidious, and memory impairment is its most

frequent feature. Deficits in other cognitive domains such as executive

and visuospatial tend to occur relatively early, while language deficits

and behavioural symptoms often manifest later in the course of the

disease.29 30

Vascular dementia is primarily caused by

cerebrovascular disease and/or impaired cerebral blood flow. There are two

main syndromes of VaD: post-stroke dementia and VaD without recent stroke.

Patients with post-stroke dementia experience a

stepwise cognitive decline that may be accompanied by other cortical

stroke signs, including aphasia and apraxia, after a clinically diagnosed

stroke. In contrast, patients with VaD without recent stroke present with

progressive or stepwise cognitive decline with prominent impairment in

executive functioning and processing speed. Brain imaging reveals silent

cerebrovascular disease including infarction or haemorrhage and is a

required element of some of the commonly used diagnostic criteria for VaD,

including the criteria of the NINDS-AIREN (National Institute of

Neurological Disorders and Stroke).31

32

Dementia with Lewy bodies is a form of dementia

caused by abnormal protein structures called Lewy bodies, which co-occur

with symptoms of Parkinsonism such as trembling, stiffness, and slowness.

Other classical features of DLB include rapid eye movement sleep

behavioural disorder and fluctuation of cognition (both are easy to elicit

from history). This disorder often causes vivid and long-lasting visual

hallucinations. Differential diagnosis of DLB includes other degenerative

dementias, especially if complicated by superimposed delirium, medication

toxicity, or seizures. Diagnosis of DLB is made primarily by the revised

criteria for clinical diagnosis.33

Frontotemporal dementia is a heterogeneous

neurodegenerative disorder characterised by frontal and/or temporal lobe

degeneration with early-onset dementia presenting with prominent changes

in social behaviour, personality, or aphasia.34

There are several clinical presentations: behavioural variant FTD, two

forms of primary progressive aphasia (PPA), non-fluent variant PPA, and

semantic variant PPA.34 Among

these, behavioural variant FTD is the most common form, characterised by

progressive personality and behavioural changes including disinhibition,

apathy, loss of empathy, hyperorality, and compulsive behaviours. The

diagnostic criteria for FTD created by an international consortium

synthesise clinical features, neuroimaging, neuropathology, and genetic

testing.35

Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia

Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia

(BPSD) were defined as ‘symptoms of disturbed perception, thought content,

mood, and behaviour frequently occurring in patients with dementia’ by

consensus among clinicians in 1996.36

37 More than 50% of people with

dementia have BPSD, and these symptoms affect both patients and their

relatives.38 A wide variety of

affective, psychotic, and behavioural symptoms and signs can be signs of

BPSD presentation, including verbal and physical aggression, agitation,

hallucinations, delusions, sleep disturbances, oppositional behaviour, and

wandering.39 Non-pharmacological

interventions have been beneficial and should be offered as the first-line

management.40 Indoor therapeutic

gardening is an effective non-pharmacological intervention to reduce BPSD,

medicine intake, and stress levels among patients with AD.41 Antipsychotic drugs are the common treatment for

BPSD,42 but evidencebased clinical

practice guidelines recommend deprescribing the drugs when the symptoms

have been stabilised or treated for 3 months or more.43 Caregivers’ burden has been associated with patients’

BPSD44; therefore, treating BPSD

brings benefits to both patients and caregivers.

Diagnostic approach

There is no single test to confirm the diagnosis of

dementia. Initial assessment should include careful histories from both

the patient and caregivers, physical examinations, cognitive assessments,

laboratory tests, and neuroimaging.

History and physical examination

Clinical evaluation of patients with suspected

dementia should start with a thorough and detailed history, taken from

both the patient and a relative or close friend.45

It is important for primary care practitioners to rule out other causes of

memory and cognitive impairments and refer appropriate patients for

specialist assessment, especially those with unusual symptoms.46 A review is necessary of the patient’s family history

and medical and psychiatric history, including obstructive sleep apnoea,

cardiovascular disease, remote head trauma, alcohol use, and depression

treatment that may contribute to cognitive decline, as well as the use of

drugs that impair cognition (eg, analgesics, anticholinergics,

psychotropic medications, and sedative-hypnotics).12 47 It is

important to note the age of onset of cognitive impairment and to ask

about family history for patients with cognitive impairment developing at

or before age 65 years. Familial AD has been reported in Hong Kong, and

these patients may need to be referred for genetic counselling and

testing.48 49 This should be followed by a complete physical

examination, including a neurological examination, to identify any

clinical features of obstructive sleep apnoea, focal neurologic signs that

may suggest vascular aetiology, or bradykinesia, rigidity, or tremors that

would suggest a Parkinsonian syndrome.12

Cognitive testing

Cognitive tests provide objective evidence about

cognitive deficits. Nevertheless, a single test will not suffice for all

assessments. Different classes of cognitive tests are better suited to

different tasks—short questionnaires are useful for rapid screening, but

multidomain tests are more useful to support a clinical diagnosis of

dementia.50 In the primary care

setting, abbreviated or brief cognitive instruments such as abbreviated

versions of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and Mini-Cog are

recommended in persons with symptoms of dementia.46

51

Mini-Mental State Examination

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) has been

the most commonly used cognitive screening instrument, although patent

protection has led to its decreased use in recent years. It has the

advantages of being brief, easy to administer, and inclusive of multiple

domains, including orientation, recall, attention, calculation, language

manipulation, and constructional praxis.52

53 Published normative data allow

interpretation of MMSE scores according to patient age and education. The

maximum score on the MMSE is 30 points. The Cantonese version of the MMSE

has been locally validated, and its cut-off points are categorised

according to the patient’s education level. For patients with more than 2

years of schooling, the cut-off score is 22.54

55 The pattern of clinical deficit

shown by the MMSE test is also important for the diagnosis of dementia.56 However, the test is not

sensitive to mild dementia, and scores may be influenced by age,

education, and language, motor and visual impairments.12 57 The MMSE

has limited ability to assess progressive cognitive decline in individual

patients over time.58

Although many ‘free’ versions of the MMSE are

available online, the official version is copyrighted.

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

The MoCA has become the more widespread initial

screening test for dementia. In early 2018, news of the President of the

United States having passed the MoCA triggered widespread interest in this

test. The MoCA is a 30-point test designed to detect cognitive impairment

in older adults. Compared with MMSE, it is more sensitive for detection of

MCI and includes items that sample a wider range of cognitive domains,

including memory, language, attention, visuospatial, and executive

functions.59 Cut-offs should be

adjusted based on education level and other appropriate norms.60 The original MoCA takes a longer time (approximately

15 minutes) to complete compared with the MMSE. Free access with

registration is available from the official website at www.mocatest.org.

The MoCA has been validated in different languages, including Chinese. The

Hong Kong–MoCA (HK-MoCA) has been shown to have comparable sensitivity to

the Cantonese version of the MMSE for detection of MCI.61 The optimal cut-off score for HK-MoCA to detect

dementia was 18/19 (sensitivity: 0.923; specificity: 0.918).61 To facilitate screening in busy clinical settings, a

few abbreviated versions of the MoCA have been validated, including the

MoCA 5-min protocol, which is feasible for telephone administration.62

Clinical Dementia Rating

Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) was designed to

assess the severity of AD in longitudinal studies and clinical trials. In

a semi-structured interview with the patient and caregiver, impairments in

six domains (memory, orientation, judgement and problem solving, community

affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care) are assessed.63 A caregiver who knows the patient well should be

present for an accurate and valid CDR assessment. The global CDR score is

assigned based on performance in each domain. It is time-consuming, but

the test has established validity and inter-rater reliability and is

useful for following disease progression over time.64

Mini-Cog test

The Mini-Cog test consists of two components: a

three-item recall test for memory and a simply scored clock drawing test.

The assessment and instructions can be accessed at www.mocatest.org.

The results of the clock drawing test are considered normal if all numbers

are present in the correct sequence and the hands display the correct time

in a readable way.65 The

advantages of the Mini-Cog include high sensitivity for predicting

dementia status, short testing time relative to the MMSE, ease of

administration, and diagnostic value not limited by the subject’s

education or language. Nevertheless, these tests are not appropriate when

assessing patients with aphasic or anomic disorders, and more prospective

data are required for further validation of this test.66

Informant interview

The AD8 Dementia Screening Interview is a brief,

eight-item questionnaire for informants to detect dementia and cognitive

impairment. Informants are asked whether the patient has exhibited any

increase in eight deficits or behaviours. A positive response to two or

more questions had a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 46%.67 The AD8 is readily administered by nurses and is

useful as a screening tool by primary healthcare doctors.68 The interview questions and scoring guidelines can be

accessed from Washington University in St Louis at http://alzheimer.wustl.edu/cdr/ad8.htm.

Neuropsychological testing

Neuropsychological testing usually involves an

extensive evaluation of multiple cognitive domains (eg, attention,

orientation, executive function, verbal memory, spatial memory, language,

calculations, mental flexibility, and conceptualisation) and may be

necessary when the bedside assessment fails to differentiate between the

changes associated with normal ageing and early dementia. Moreover,

neuropsychological testing can identify patterns of deficits that suggest

a particular cause of dementia and assist in narrowing the differential

diagnosis of dementia syndrome. However, these scores can also be

influenced by education and age.18

69

Diagnosing Mrs Wong’s dementia

Mrs Wong scored 18 on the HK-MoCA assessment, which

was the cut-off score for dementia adjusted by her age and education

level.

Mrs Wong presented with a memory complaint

evidenced by the collateral history from her family members. In her daily

life, she was noted to have impaired executive functioning (inability to

handle banking) and topographic disorientation (getting lost while

shopping alone). Her HK-MoCA score also confirms the presence of memory

impairment. Moreover, her impairment has reached the point of interfering

with her social functioning. Therefore, Mrs Wong meets the clinical

definition of dementia.

Neuroimaging

Although the literature regarding indications for

neuroimaging in evaluating dementia remains inconclusive, most dementia

specialists suggest that a structural brain image be obtained for newly

diagnosed patients to assess any cerebrovascular lesions, neoplasms,

subdural haematomas, or hydrocephalus. Imaging analysis techniques that

quantify the volume of brain structures or lesions may be useful in the

future for diagnosing AD. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

(FDG-PET) and other functional neuroimaging techniques are usually used by

specialists to assess complex or unclear cases of neurodegenerative

dementia.18 70 Occasionally, PET imaging with different tracers for

biomarkers (eg, amyloid tracers with 18F-florbetapir) in

dementia may be indicated for the differential diagnosis of dementing

disorders, especially in the presence of overlapping clinical features.71 Scanning with 18F-florbetapir

is not available in Hong Kong, but imaging with Pittsburgh Compound B and

18F-flutametamol are available in Hong Kong. A local study has

shown that 18FDG-PET with or without 11C-PIB brain

imaging improved the accuracy of diagnosis of dementia subtype in 36% of a

case series of Chinese dementia patients.72

Volumetric analysis of magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) may identify patterns of regional atrophy that are more specific in

certain subtypes of dementia. In some studies, volumetric MRI has shown

that patients with AD had a greater degree of hippocampal atrophy than

patients with DLB had, and patients with DLB had more pronounced cortical

atrophy than patients with Parkinson disease dementia.73 74

Although basic structural brain imaging (computed

tomography or MRI) can be obtained in the primary care setting, highly

specialised imaging is recommended for specialist settings only, as most

studies using specialised modalities have focused on subtyping rather than

the existence versus absence of dementia.46

Laboratory tests

Laboratory tests should be performed to identify

infectious, metabolic, toxic, and inflammatory disorders that can cause

neuropsychological impairment. The American Academy of Neurology

recommends screening for vitamin B12 deficiency and hypothyroidism in

patients with dementia. Screening for neurosyphilis is not recommended

unless there is a high clinical suspicion. Because of the potential for

both false positives and false negatives, genetic testing is not currently

recommended unless a specific characteristic family history is present.

Lumbar puncture, electroencephalography, and/or serologic tests may be

useful in patients with dementia who are aged <55 years or in those

with rapid progression, unusual dementia, or immunosuppression.12 18 75

Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers (total-tau and p-tau)

Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers (including Aβ42

protein, total tau, and phospho-tau) are widely investigated biomarkers of

AD and can be supportive of a diagnosis of AD but are not yet recommended

for routine diagnostic purposes.30

76 None of these tests are valid

as a standalone diagnostic test. These cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers can

be measured only in private laboratory settings on a self-paid basis. Such

tests are not well accepted in Hong Kong because of the

invasiveness of collecting cerebrospinal fluid.

Determining the underlying cause(s) of Mrs Wong’s

dementia

Delirium or depression, which may mimic symptoms of

dementia, should first be excluded. Medication history is checked to rule

out any drugs with potential anticholinergic properties, which may also

cause cognitive impairment.

With vascular risk factors (a history of

hypertension and diabetes mellitus), there is a potential contributing

cerebrovascular component to Mrs Wong’s dementia. Mrs Wong did not have a

history of clinical stroke and her dementia is of a slow progressive

course, not one of the stroke-like episodes of stepwise decline, as might

be the case in VaD.

On physical examination, Mrs Wong was not found to

have any Parkinsonism features or abnormal neurological signs that would

be suggestive of dementia related to Parkinsonism. There were no features

suggestive of DLB. Screening for other reversible causes of dementia,

including thyroid disorder and vitamin B12 deficiency, were negative. Mrs

Wong underwent a computed tomography scan of the brain, which showed mild

cerebral atrophy and some periventricular ischaemia. On the basis of these

findings, Mrs Wong met the clinical diagnostic criteria for AD.

Role of primary healthcare professionals

The World Alzheimer Report 2016 indicated that

with the rising prevalence of dementia, the usual specialist-led approach

may not expand rapidly enough to keep up with the increased need for care.

Thus, primary and community care should have a more prominent role in

improving the coverage of diagnosis and continuing dementia care.77

Screening for dementia among people at risk in

primary care practices was found to significantly promote the recognition

of dementia, but because of the risk of receiving a false-positive

diagnosis, additional diagnostic assessment should be mandatory.78 Other perspectives exist on systematic consideration

of the respective roles of primary and specialty care in long-range

dementia care.79 Following recent

research on the causes of and treatments for cognitive impairment, changes

in clinical practice have occurred, and there is increased awareness of

cognitive impairment detection during routine health check-ups in the

primary care setting. The objectives of primary care physicians (PCPs) are

to identify AD and other types of dementia, arrive at early diagnoses, and

prevent and treat AD complications such as falls and malnutrition. It is

also important for PCPs to develop close interactions with specialists,

including geriatricians, psychogeriatricians, and neurologists.80 For complex case diagnosis and management, a prompt

referral to a specialist is required.

In one study, the collaborative care delivered by

an interdisciplinary team resulted in a significant improvement in both

the quality of care and BPSD among both primary care patients and their

caregivers.81 Structured

partnerships among primary healthcare professionals may serve as bridges

between primary care, specialty care, and community-based services.82 To facilitate such management, it is advised that

PCPs include a relevant history in the referral letter to facilitate

subtyping of the patient’s dementia (online supplementary Appendix).

Because of primary care providers’ growing role,

there is a need for better professional education and training in both

diagnosis and management of dementia. In the United Kingdom, general

practitioners work one session per week in their local Memory Clinics,

where they can learn directly from experts and establish working

relationships with secondary dementia caregivers. It is highly recommended

that we adopt the same educational programme in Hong Kong. In addition,

primary doctors can refer to the Hong Kong Reference Framework for

Preventive Care for Older Adults in Primary Care Settings–Module for

Cognitive Impairment (2017) written by the Primary Care Office, Department

of Health.83

Conclusion

It is important that dementia is recognised at the

earliest stage and that timely evaluations are carried out to initiate

appropriate therapy, with patients able to participate in management

decisions. The initial step in evaluation of a patient with suspected

dementia should be the taking of a focused history of cognitive and

behavioural changes, followed by a complete physical examination.

Delirium, depression, and MCI should be considered in the differential

diagnosis of memory impairment. Many useful screening tools are now

available for dementia. Once a diagnosis of dementia has been made,

neuroimaging (eg, brain computed tomography or MRI scan) and laboratory

tests should be performed to rule out any reversible causes of dementia.

Advanced imaging, such as FDG-PET imaging or amyloid PET scanning with

special tracers, may be indicated for specific cases to reach a definitive

diagnosis. In the future, primary care will play a more prominent role in

dementia management. Close interactions between PCPs and specialists are

needed for complex case management, especially those requiring

pharmacological management.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to

the concept or design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis or

interpretation of data, drafting of the article, and critical revision for

important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Mr David CH Lau,

who offered professional advice on cognitive tests.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, JKH Luk was not

involved in the peer review process of the article. Other authors have

declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Qiu C, Kivipelto M, von Strauss E.

Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease: occurrence, determinants, and

strategies toward intervention. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2009;11:111-28.

2. Catindig JA, Venketasubramanian N, Ikram

MK, Chen C. Epidemiology of dementia in Asia: insights on prevalence,

trends and novel risk factors. J Neurol Sci 2012;321:11-6. Crossref

3. Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M, et al.

World Alzheimer Report 2015—The Global Impact of Dementia. London:

Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2015.

4. Chan KY, Wang W, Wu JJ, et al.

Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia in China,

1990-2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet 2013;381:2016-23. Crossref

5. Prince M, Bryce R, Ferri C. World

Alzheimer report 2011: The benefits of early diagnosis and intervention.

London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2011.

6. Boustani M, Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW,

et al. Implementing a screening and diagnosis program for dementia in

primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:572-7. Crossref

7. Ross GW, Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, et al.

Frequency and characteristics of silent dementia among elderly

Japanese-American men. The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. JAMA 1997;277:800-5.

Crossref

8. Fahy M, Wald C, Walker Z, Livingston G.

Secrets and lies: the dilemma of disclosing the diagnosis to an adult with

dementia. Age Ageing 2003;32:439-41. Crossref

9. Tripathi M, Vibha D. Reversible

dementias. Indian J Psychiatry 2009;51 Suppl 1:S52-5.

10. American Psychiatric Association.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). 5th ed.

Arlington, VA: Arlington; 2013. Crossref

11. Sachdev PS, Blacker D, Blazer DG, et

al. Classifying neurocognitive disorders: the DSM-5 approach. Nat Rev

Neurol 2014;10:634-42. Crossref

12. Ross GW, Bowen JD. The diagnosis and

differential diagnosis of dementia. Med Clin North Am 2002;86:455-76. Crossref

13. Howieson DB, Holm LA, Kaye JA, Oken

BS, Howieson J. Neurologic function in the optimally healthy oldest old.

Neuropsychological evaluation. Neurology 1993;43:1882-6. Crossref

14. Small SA, Stern Y, Tang M, Mayeux R.

Selective decline in memory function among healthy elderly. Neurology

1999;52:1392-6. Crossref

15. Crook T, Bartus RT, Ferris SH,

Whitehouse P, Cohen GD, Gershon S. Age-associated memory impairment:

proposed diagnostic criteria and measures of clinical change—report of a

national institute of mental health work group. Dev Neuropsychol

1986;2:261-76. Crossref

16. Levy R. Aging-associated cognitive

decline. Working Party of the International Psychogeriatric Association in

collaboration with the World Health Organization. Int Psychogeriatr

1994;6:63-8. Crossref

17. Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC,

Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical

characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol 1999;56:303-8. Crossref

18. Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M,

Tangalos EG, Cummings JL, DeKosky ST. Practice parameter: early detection

of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report

of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of

Neurology. Neurology 2001;56:1133-42. Crossref

19. Pandya SY, Clem MA, Silva LM, Woon FL.

Does mild cognitive impairment always lead to dementia? A review. J Neurol

Sci 2016;369:57-62. Crossref

20. Lopez OL, Becker JT, Chang YF, et al.

Incidence of mild cognitive impairment in the Pittsburgh Cardiovascular

Health Study–Cognition Study. Neurology 2012;79:1599-606. Crossref

21. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al.

Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a

preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1982-1983;17:37-49. Crossref

22. Jorm AF, Fratiglioni L, Winblad B.

Differential diagnosis in dementia. Principal components analysis of

clinical data from a population survey. Arch Neurol 1993;50:72-7. Crossref

23. Andrew MK, Freter SH, Rockwood K.

Prevalence and outcomes of delirium in community and non-acute care

settings in people without dementia: a report from the Canadian Study of

Health and Aging. BMC Med 2006;4:15. Crossref

24. Levkoff S, Cleary P, Liptzin B, Evans

DA. Epidemiology of delirium: an overview of research issues and findings.

Int Psychogeriatr 1991;3:149-67. Crossref

25. Vasilevskis EE, Han JH, Hughes CG,

Wesley Ely E. Epidemiology and risk factors for delirium across hospital

settings. Best Pact Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2012;26:277-87. Crossref

26. Leung JL, Leung VC, Leung CM, Pan PC.

Clinical utility and validation of two instruments (the Confusion

Assessment Method Algorithm and the Chinese version of Nursing Delirium

Screening Scale) to detect delirium in geriatric inpatients. Gen Hosp

Psychiatry 2008;30:171-6. Crossref

27. Rizzi L, Rosset I, Roriz-Cruz M.

Global epidemiology of dementia: Alzheimer’s and vascular types. Biomed

Res Int 2014;2014:908915. Crossref

28. Vann Jones SA, O’Brien JT. The

prevalence and incidence of dementia with Lewy bodies: a systematic review

of population and clinical studies. Psychol Med 2014;44:673- 83. Crossref

29. Ballard C, Gauthier S, Corbett A,

Brayne C, Aarsland D, Jones E. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet

2011;377:1019-31. Crossref

30. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et

al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations

from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on

diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement

2011;7:263-9.Crossref

31. Hachinski V, Iadecola C, Petersen RC,

et al. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–Canadian

Stroke Network vascular cognitive impairment harmonization standards.

Stroke 2006;37:2220-41. Crossref

32. Román GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T,

et al. Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report

of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology 1993;43:250-60. Crossref

33. McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et

al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth

consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 2017;89:88-100. Crossref

34. Olney NT, Spina S, Miller BL.

Frontotemporal dementia. Neurol Clin 2017;35:339-74. Crossref

35. Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, et

al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant

of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 2011;134(Pt 9):2456-77.

36. Finkel SI, Silva JC, Cohen GD, Miller

S, Sartorius N. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a

consensus statement on current knowledge and implications for research and

treatment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1998;6:97-100. Crossref

37. International Psychogeriatric

Association. The IPA complete guides to behavioral and psychological

symptoms of dementia. Milwaukee, WI; 2010.

38. Hersch EC, Falzgraf S. Management of

the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Clin Interv Aging

2007;2:611-21. Crossref

39. Tible OP, Riese F, Savaskan E, von

Gunten A. Best practice in the management of behavioural and psychological

symptoms of dementia. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2017;10:297-309. Crossref

40. Bessey LJ, Walaszek A. Management of

behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Curr Psychiatry Rep

2019;21:66. Crossref

41. Pedrinolla A, Tamburin S, Brasioli A,

et al. An indoor therapeutic garden for behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s

disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimers Dis 2019;71:813-23. Crossref

42. Luk JH. Pharmacological management of

behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Asian J Gerontol

Geriatr 2017;12:65-8.

43. Bjerre LM, Farrell B, Hogel M, et al.

Deprescribing antipsychotics for behavioural and psychological symptoms of

dementia and insomnia: evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Can Fam

Physician 2018;64:17-27.

44. Huang SS, Lee MC, Liao YC, Wang WF,

Lai TJ. Caregiver burden associated with behavioral and psychological

symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in Taiwanese elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr

2012;55:55-9. Crossref

45. Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Petersen RC.

Essentials of the proper diagnoses of mild cognitive impairment, dementia,

and major subtypes of dementia. Mayo Clin Proc 2003;78:1290-308. Crossref

46. Pink J, O’Brien J, Robinson L, Longson

D; Guideline Committee. Dementia: assessment, management and support:

summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2018;361:k2438. Crossref

47. Campbell NL, Boustani MA, Lane KA, et

al. Use of anticholinergics and the risk of cognitive impairment in an

African American population. Neurology 2010;75:152-9. Crossref

48. Shea YF, Chu LW, Chan AO, Ha J, Li Y,

Song YQ. A systematic review of familial Alzheimer’s disease: differences

in presentation of clinical features among three mutated genes and

potential ethnic differences. J Formos Med Assoc 2016;115:67-75. Crossref

49. Shea YF, Chu LW, Lee SC, Chan AO. The

first case series of Chinese patients in Hong Kong with familial

Alzheimer’s disease compared with those with biomarker-confirmed sporadic

late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Hong Kong Med J 2017;23:579-85. Crossref

50. Brown J. The use and misuse of short

cognitive tests in the diagnosis of dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg

Psychiatry 2015;86:680-5. Crossref

51. Creavin S, Wisniewski S, Noel-Storr A,

Cullum S; MMSE review team. Cognitive tests to help diagnose dementia in

symptomatic people in primary care and the community. Br J Gen Pract

2018;68:149-50. Crossref

52. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR.

“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of

patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189-98. Crossref

53. Tangalos EG, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, et

al. The Mini-Mental State Examination in general medical practice:

clinical utility and acceptance. Mayo Clin Proc 1996;71:829-37. Crossref

54. Chiu HF, Lee HC, Chung WS, Kwong PK.

Reliability and validity of the Cantonese version of Mini-Mental State

Examination—a preliminary study. JHKC Psych 1994;4:25-8.

55. Chiu HF, Lam C, Chi I, et al.

Prevalence of dementia in Chinese elderly in Hong Kong. Neurology

1998;50:1002-9. Crossref

56. Anthony JC, LeResche L, Niaz U, von

Korff MR, Folstein MF. Limits of the ‘Mini-Mental State’ as a screening

test for dementia and delirium among hospital patients. Psychol Med

1982;12:397-408. Crossref

57. Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS,

Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination

by age and educational level. JAMA 1993;269:2386-91. Crossref

58. Creavin ST, Wisniewski S, Noel-Storr

AH, et al. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of

dementia in clinically unevaluated people aged 65 and over in community

and primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2016;(1):CD011145.

59. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian

V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool

for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:695-9. Crossref

60. Rossetti HC, Lacritz LH, Cullum CM,

Weiner MF. Normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in

a population-based sample. Neurology 2011;77:1272-5. Crossref

61. Yeung PY, Wong LL, Chan CC, Leung JL,

Yung CY. A validation study of the Hong Kong version of Montreal Cognitive

Assessment (HK-MoCA) in Chinese older adults in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J

2014;20:504-10. Crossref

62. Wong A, Nyenhuis D, Black SE, et al.

Montreal Cognitive Assessment 5-minute protocol is a brief, valid,

reliable, and feasible cognitive screen for telephone administration.

Stroke 2015;46:1059-64. Crossref

63. Washington University in St Louis.

CDR® Dementia Staging Instrument. Available from: https://knightadrc.

wustl.edu/cdr/cdr.htm. Accessed 30 Aug 2019.

64. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia

Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412-4.

Crossref

65. Mini-Cog©–Screening for cognitive

impairment in older adults. Available from: https://mini-cog.com/.

Accessed 30 Aug 2019.

66. Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M,

Vitaliano P, Dokmak A. The Mini-Cog: a cognitive ‘vital signs’ measure for

dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry

2000;15:1021-7. Crossref

67. Galvin JE, Roe CM, Xiong C, Morris JC.

Validity and reliability of the AD8 informant interview in dementia.

Neurology 2006;67:1942-8. Crossref

68. Shaik MA, Khoo CH, Thiagarajah AG, et

al. Pilot evaluation of a dementia case finding clinical service using the

informant AD8 for at-risk older adults in primary health care: a brief

report. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:673.e5-8. Crossref

69. Cahn DA, Salmon DP, Butters N, et al.

Detection of dementia of the Alzheimer type in a population-based sample:

neuropsychological test performance. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1995;1:252-60.

Crossref

70. Corey-Bloom J, Thal LJ, Galasko D, et

al. Diagnosis and evaluation of dementia. Neurology 1995;45:211-8. Crossref

71. Berti V, Pupi A, Mosconi L. PET/CT in

diagnosis of dementia. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2011;12281:81-92. Crossref

72. Shea YF, Ha J, Lee SC, Chu LW. Impact

of 18FDG PET and 11C-PIB PET brain imaging on the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s

disease and other dementias in a regional memory clinic in Hong Kong. Hong

Kong Med J 2016;22:327-33. Crossref

73. Barber R, Ballard C, McKeith IG,

Gholkar A, O’Brien JT. MRI volumetric study of dementia with Lewy bodies;

a comparison with AD and vascular dementia. Neurology 2000;54:1304-9. Crossref

74. Beyer MK, Larsen JP, Aarsland D. Gray

matter atrophy in Parkinson disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy

bodies. Neurology 2007;69:747-54. Crossref

75. Geschwind MD, Shu H, Haman A, Sejvar

JJ, Miller BL. Rapidly progressive dementia. Ann Neurol 2008;64:97-108. Crossref

76. Shea YF, Chu LW, Zhou L, et al.

Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease in Chinese patients:

a pilot study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2013;28:769-75. Crossref

77. Prince M, Comas-Herrera A, Knapp M,

Guerchet M, Karagiannidou M. World Alzheimer Report 2016—improving

healthcare for people living with dementia: coverage, quality and costs

now and in the future. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2016.

78. Eichler T, Thyrian JR, Hertel J, et

al. Rates of formal diagnosis of dementia in primary care: the effect of

screening. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2015;1:87-93. Crossref

79. Borson S, Frank L, Bayley PJ, et al.

Improving dementia care: the role of screening and detection of cognitive

impairment. Alzheimers Dement 2013;9:151-9. Crossref

80. Cohen CA, Pringle D, LeDuc L. Dementia

caregiving: the role of the primary care physician. Can J Neurol Sci

2001;28 Suppl 1:S72-6. Crossref

81. Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt

FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with

Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA

2006;295:2148-57. Crossref

82. Reuben DB, Roth CP, Frank JC, et al.

Assessing care of vulnerable elders—Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study of

a practice redesign intervention to improve the quality of dementia care.

J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:324-9. Crossref

83. Hong Kong Reference Framework for

Preventive Care for Older Adults in Primary Care Settings. Module on

Cognitive Impairment. Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR Government;

2017.