© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Management of bilateral rhino-orbital cerebral

mucormycosis

Stacey C Lam, MB, ChB, MRCSEd1,2;

Hunter KL Yuen, MRCS, FCOphthHK1,2

1 Department of Ophthalmology and Visual

Sciences, Hong Kong Eye Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Ophthalmology and Visual

Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Stacey C Lam (staceylam@gmail.com)

Introduction

Mucormycosis is a group of invasive infections

caused by filamentous Mucorales fungi, most commonly Rhizopus

species.1 Although rare, Mucorales

is the third most common cause of fungal infection after Candida

and Aspergillus species.2

Mucorales are opportunistic fungi that can be found in soil, as well as

the mouth, nasal tract, and faeces of healthy individuals. Contact with

Mucorales occurs through spore inhalation; the organism can then invade

the paranasal sinus mucosa and erode through the bony walls of the orbit

and skull base into the brain, causing orbital and cerebral infections,

respectively. Fungal growth is enhanced in high-glucose, high-iron, and

acidic environments.1 Moreover,

elevated glucose and iron levels up-regulate glucose-regulated protein 78

(GRP78) and promote endothelial cell invasion.3

The hallmark of mucormycosis is angioinvasion, causing arteritis, vessel

thrombosis, tissue ischaemia, and necrosis with bony destruction.1 Angioinvasion also allows the organism to disseminate

to other organs, and the ischaemic necrosis impedes the delivery of

antifungal agents to target sites.

Rhino-orbital cerebral mucormycosis (ROCM) is a

rare but life-threatening fungal infection that occurs in

immunocompromised or diabetic patients. Bilateral involvement in ROCM has

been reported in only a few cases.1

4 5

Exemplar case

Rhino-orbital cerebral mucormycosis is usually

unilateral, with the infection spreading from the nasal mucosa to the

sinuses, orbit and brain. We experienced a severe case of bilateral ROCM.

A 70-year-old obese woman presented with poor appetite and right eye pain

for 10 days. She had a history of well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus

(haemoglobin A1c 6.5%, 10 months before presentation). On admission, she

was febrile, with right upper lid and facial swelling, right proptosis and

ophthalmoplegia. She had elevated blood glucose (21.8 mmol/L), elevated

haemoglobin A1c (17.9%), and urine test revealed ketone bodies and

leukocytes. Her preliminary diagnosis was right orbital cellulitis with

sinusitis, diabetic ketoacidosis, and urinary tract infection. Despite

insulin infusion and hydration, aggressive antibiotics with ceftriaxone,

metronidazole, and amphotericin B, the patient developed septic shock,

acute coronary syndrome, frontal lobe stroke, and acute kidney injury

requiring dialysis.

At 3 days after admission, the patient developed

signs of right endophthalmitis and right forehead phlebitis. Urgent

aqueous and vitreous tap with injection of intravitreal vancomycin and

ceftazidime was performed; both cultures were negative. Nasal biopsy

yielded Rhizopus oryzae and mucormycosis, and she was started on

systemic liposomal amphotericin B, posaconazole and anidulafungin.

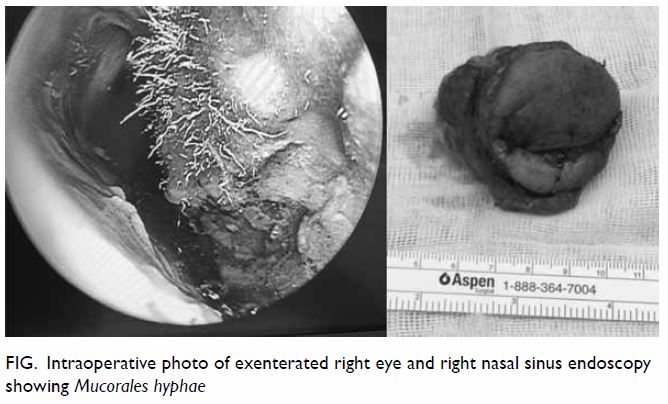

Infected tissue was urgently debrided by orbital exenteration with

functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Intra-operative endoscopy showed

nasal hyphae (Fig). After surgery, the wound was irrigated daily

with amphotericin B. Despite local and systemic antifungal treatment, the

infection was not controlled and 1 week later, spread to the contralateral

sinus, orbit, and eye with endophthalmitis. The patient succumbed 4 weeks

after admission.

Figure. Intraoperative photo of exenterated right eye and right nasal sinus endoscopy showing Mucorales hyphae

Discussion

Effective treatment of ROCM includes (1) early

diagnosis; (2) reversal of underlying risk factors; (3) surgical

debridement where applicable; and (4) prompt antifungal therapy.2

First, early diagnosis depends on a high index of

clinical suspicion. Onset of mucormycosis can be nonspecific with malaise

and fever. With orbital involvement, there can be orbital cellulitis,

orbital apex syndrome, and cavernous sinus thrombosis. Occurrence of

mental state changes, hemiparesis, or seizures suggest intracranial

extension.2 Endoscopy and

radiography appearance lag behind clinical progression, so in suspicious

cases, blind biopsies of sinus mucosa or thickened extraocular muscles are

warranted.2 Computed tomography

findings are nonspecific, with sinusitis or thickening of extraocular

muscles, but may be useful in delineating the extent of the infection and

in guiding surgical debridement.2

Magnetic resonance imaging is more sensitive than computed tomography for

detecting orbital and cerebral involvement, and may demonstrate focal lack

of enhancement with devitalised sinus mucosa.6

Definitive diagnosis is made by demonstration of fungal hyphae in tissue

specimens. Fungal invasion may be patchy, so multiple biopsies may be

required for definitive diagnosis.2

Second, it is critical to reverse any underlying

immunocompromised state. This includes aggressive management to restore

euglycaemia and normal acid base in diabetic ketoacidotic patients,

stopping immunosuppressive agents, and avoiding iron and blood

transfusions.2 Other therapies

include iron chelating agents, hyperbaric oxygen, and adjunctive cytokine

therapy.2 5

Third, surgical debridement is critical, as blood

vessel thrombosis and resulting tissue necrosis impedes delivery of

necessary antifungal agents to the site of infection. Orbital exenteration

has been found to make a significant difference in survival only in

patients with fever.6 Involved

tissues rarely bleed, so surgeons should debride until well-perfused

bleeding tissue is encountered. Daily repeated debridement may be needed,

and subsequent surgeries may be needed for reconstruction when the

infection subsides. Bilateral exenteration for bilateral mucormycosis is

uncommon with poor prognosis, but survival from bilateral exenteration has

been reported.5 For our case,

bilateral exenteration was not attempted as the patient already had poor

prognosis and the surgery would be extremely disfiguring if the patient

survived.

Fourth, first-line antifungal treatment includes

lipid-based amphotericin B, which destroys the cell wall of the fungus.

This is given systemically, locally irrigated, and packed in affected

areas. Fluconazole, voriconazole, and itraconazole do not have reliable

activity against mucormycosis.2

Posaconazole, a trizole antifungal, has been suggested as a salvage

therapy for those who are refractory or intolerant to polyene.

Poor survival is associated with delayed diagnosis

and treatment (61% if commenced within first 12 days of presentation

compared to 33% if after 13 days), cerebral involvement (hemiparesis or

hemiplegia), bilateral sinus involvement, renal disease, and possibly

facial necrosis.7

Owing to the aggressive nature of mucormycosis, the

mortality rate is high. Although an infrequent diagnosis, there should be

a high index of suspicion for mucormycosis in patients with predisposing

factors and orbital symptoms, in order to prevent treatment delay.

Author contributions

HKL Yuen contributed to the concept of study,

acquisition and analysis of data, and critical revision for important

intellectual content. SC Lam wrote the article.

Conflicts of interest

As an epidemiology advisor of the Editorial Board,

HKL Yuen was not involved in the peer review process of the article. The

other author has disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration

of Helsinki.

References

1. Jiang N, Zhao G, Yang S, et al. A

retrospective analysis of eleven cases of invasive rhino-orbito-cerebral

mucormycosis presented with orbital apex syndrome initially. BMC

Ophthalmol 2016;16:10. Crossref

2. Spellberg B, Edwards J Jr, Ibrahim A.

Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and

management. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005;18:556-69. Crossref

3. Liu M, Spellberg B, Phan QT, et al. The

endothelial cell receptor GRP78 is required for mucormycosis pathogenesis

in diabetic mice. J Clin Invest 2010;120:1914-24. Crossref

4. Oladeji S, Amusa Y, Olabanji J, Adisa A.

Rhinocerebral mucormycosis in a diabetic case report. J West African Coll

Surg 2013;3:93-102.

5. De La Paz MA, Patrinely JR, Marines HM,

Appling WD. Adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of bilateral

cerebro-rhino-orbital mucormycosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1992;114:208-11. Crossref

6. Hargrove RN, Wesley RE, Klippenstein KA,

Fleming JC, Haik BG. Indications for orbital exenteration in mucormycosis.

Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;22:286-91. Crossref

7. Ferry AP, Abedi S. Diagnosis and

management of rhino-orbitocerebral mucormycosis (phycomycosis). A report

of 16 personally observed cases. Ophthalmology 1983;90:1096-104. Crossref