Hong

Kong Med J 2019 Aug;25(4):271–8 | Epub 5 Aug 2019

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Prevalence of obstetric anal sphincter injury following

vaginal delivery in primiparous women: a retrospective analysis

Sonia PK Kwok, MB, ChB, MRCOG; Osanna YK Wan,

FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG; Rachel YK Cheung, FHKAM

(Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG; LL Lee, MSc; Jacqueline PW Chung,

FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology), FHKCOG; Symphorosa SC Chan, MD, FRCOG

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The

Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr Symphorosa SC Chan (symphorosa@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Obstetric anal

sphincter injuries (OASIS) may be underdetected in primiparous women.

This study evaluated the prevalence of OASIS in primiparous women after

normal vaginal delivery or instrumental delivery using endoanal

ultrasound (US) during postnatal follow-up.

Methods: This study

retrospectively analysed endoanal US data collected during postnatal

follow-up (6-12 months after vaginal delivery) at a tertiary hospital in

Hong Kong. Offline analysis to determine the prevalence of OASIS was

performed by two researchers who were blinded to the clinical diagnosis.

Symptoms of faecal and flatal incontinence were assessed with the Pelvic

Floor Distress Inventory.

Results: Of 542 women included

in the study, 205 had normal vaginal delivery and 337 had instrumental

delivery. The prevalence of OASIS detected by endoanal US was 7.8% (95%

confidence interval [CI]=4.1%-11.5%) in the normal vaginal delivery

group and 5.6% (95% CI=3.1%-8.1%) in the instrumental delivery group.

Overall, 82.9% of women with OASIS on endoanal US did not show clinical

signs of OASIS. Birth weight was significantly higher in the OASIS group

(P=0.012). At 6 to 12 months after delivery, 5.5% of women reported

faecal incontinence and 17.9% reported flatal incontinence, but OASIS

was not associated with these symptoms.

Conclusions: Additional training

for midwives and doctors may improve OASIS detection.

New knowledge added by this study

- The prevalence of obstetric anal sphincter injury in primiparous women was 7.8% in the normal vaginal delivery group and 5.6% in the instrumental delivery group.

- Most obstetric anal sphincter injuries, as determined by endoanal ultrasound, were not detected clinically. At 6 to 12 months after delivery, obstetric anal sphincter injuries were not associated with symptoms of faecal or flatal incontinence, but a longer-term study is needed to confirm these findings.

- Obstetric anal sphincter injuries occur at similar rates during normal vaginal delivery and instrumental delivery. Detailed vaginal and rectal examinations are recommended after both types of deliveries.

- Additional training for midwives and doctors may improve the detection of obstetric anal sphincter injury.

Introduction

Obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) is a

serious complication of vaginal delivery that is associated with an

increased risk of anal incontinence (complaint of involuntary loss of

faeces or flatus).1 The incidence

of OASIS is reportedly much lower in Hong Kong (0.32%) than in other

countries, such as the United Kingdom, Norway, and Sweden (2.9%-4.2%).2 3 4 5 This could be

affected by a number of factors. First, delivery practices in Hong Kong

are quite different from elsewhere in the world, such that they include

the use of a hands-on approach to protect the perineum and liberal use of

episiotomy.6 The episiotomy rates

are reportedly high in Hong Kong: 83.7% for primiparous women and 54.8%

for multiparous women.5 Moreover,

in Hong Kong, a left mediolateral episiotomy is used, whereas midline

episiotomy or right mediolateral episiotomy are used in many other parts

of the world.7 Second, there may be

ethnic differences in pelvic floor biometry. In particular, Chinese women

have a smaller hiatal dimension and reduced pelvic organ mobility.8 It is unclear how these differences in practice and

pelvic floor biometry influence the incidence of OASIS.

Importantly, it is also possible that the reduced

incidence of OASIS in Hong Kong is a result of underdetection. In a recent

local prospective observational study, women were assessed by a single

experienced clinician via rectal examination after either normal or

instrumental vaginal delivery; the results of that study showed that the

incidence of OASIS in primiparous Asian women in Hong Kong was 10%,6 which suggests that the OASIS rate might be higher than

previously published. Obstetric anal sphincter injuries that are

identified after an extended interval (such as during postnatal follow-up)

is regarded as occult OASIS. There is limited information in the

literature regarding occult OASIS; thus far, studies have been conducted

in the United Kingdom and Australia.9

10

The use of endoanal ultrasound (US) may facilitate

identification of OASIS.11

Endoanal US comprises a non-invasive assessment modality and is regarded

as the gold standard in studies of anal sphincter injury.9 11 Moreover,

all cases of clinically identified OASIS can also be identified on

endoanal US.9 The aim of this study

was to determine the prevalence of OASIS in primiparous women after normal

vaginal delivery or instrumental delivery using endoanal US during

postnatal follow-up. Understanding the prevalence and detection rates of

OASIS can help inform training policies for midwives and doctors on the

awareness and detection of OASIS.

Methods

Patients and study design

This was a retrospective analysis of archived US

volumes from two previously published studies that were performed at a

tertiary university hospital in Hong Kong. The initial study recruited 442

nulliparous women in the first trimester, during the period from August

2009 to September 2010.12 13 The second study recruited 292 primiparous women at 1

to 3 days after instrumental delivery, during the period from September

2011 to May 2012. None of the women in either study reported symptoms of

pelvic floor disorders, including faecal incontinence to solid or loose

stool, before pregnancy.14 Details

of deliveries, including any occurrence of perineal tearing, were recorded

after each delivery. Ethics approval was obtained from The Joint Chinese

University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research

Ethics Committee (Ref CRE-2013.332). The STROBE (Strengthening the

Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were

followed in the preparation of this report.15

Delivery and immediate assessment

Generally, each woman underwent perineal

examination by the attending midwife or doctor who conducted the delivery,

immediately after vaginal delivery. This information was immediately

recorded in the medical record. Third- or fourth-degree tears were

assessed and repaired by a trained obstetrician. The anorectal mucosa was

repaired by continuous or interrupted sutures with 3-O Vicryl. Internal

anal sphincter tears were repaired separately by interrupted end-to-end

sutures with 2-O Vicryl. External anal sphincter (EAS) tears were repaired

by overlapping or end-to-end sutures with 2-O Vicryl. Perineal muscles and

the vagina were repaired with 2-O Vicryl. The diagnosis and operative

record of each woman were immediately entered into the electronic medical

record. The degree of perineal tear was defined using Sultan’s

classification of perineal trauma.16

Follow-up assessment

During postnatal follow-up (6-12 months after

delivery), the urinary, bowel, and prolapse symptoms of each woman, as

well as their quality of life, were assessed using the Chinese Pelvic

Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire

(PFIQ).17 Assessment of the anal

sphincter was performed with endoanal US using a 10-MHz 360-degree

rotating probe (Focus 400, BK Medical; Gentofte, Denmark) with the woman

in the lithotomy position. Automatic image acquisition was performed with

two volumes stored for each woman.

Blinded offline analysis of endoanal ultrasound

Offline analysis of the endoanal US volumes was

performed in 2018 by two experienced obstetricians (OYKW, SSCC) who were

blinded to the clinical diagnosis and questionnaire information. An anal

sphincter defect was defined as a discontinuity of >30 degrees in

endosonographic images of the internal (hypoechoic ring) and/or external

(mixed echogenic ring) sphincters.18

A partial-thickness EAS injury was defined as a defect of <50%

thickness of the EAS, whereas a defect of >50% of the EAS was regarded

as a full-thickness injury. We considered any EAS and/or internal anal

sphincter injury to be OASIS. This follows the clinical classification of

OASIS by Sultan.16 Each researcher

reviewed all endoanal US volumes independently. Any discrepancies were

resolved by consensus review of the relevant US volumes.

Definitions of incontinence

The PFDI and PFIQ are comprehensive validated

instruments which assess the symptoms and impact of pelvic floor

disorders.17 In this study, faecal

incontinence was defined as an affirmative response to either item 38 (“Do

you usually lose stool beyond your control if your stool is well formed?”)

or item 39 (“Do you lose stool beyond your control if your stool is loose

or liquid?”) of the PFDI. Flatal incontinence was defined as an

affirmative response to item 40 (“Do you usually lose gas from the rectum

beyond your control?”) of the PFDI.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed by SPSS (Window version 22.0;

IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States). Descriptive analyses were used to

study the prevalence of OASIS on endoanal US. Means were compared between

groups using the independent-samples t test. Comparisons of

frequencies were made using the Chi squared test or Fisher’s exact test,

where appropriate. Univariate analysis was performed to evaluate the

influence of potential risk factors on OASIS. Differences with P<0.05

were considered to be statistically significant. Power calculations were

not performed with regard to this specific research question, as this

study comprised a subanalysis of two prior projects, as described earlier

in this paper.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 544 women who had vaginal delivery were

enrolled in this study; 207 had normal vaginal delivery and 337 had

instrumental delivery (285 vacuum extraction, 52 forceps). Ultrasound

images were suboptimal for two women who had normal vaginal delivery;

these women were excluded from the analysis.

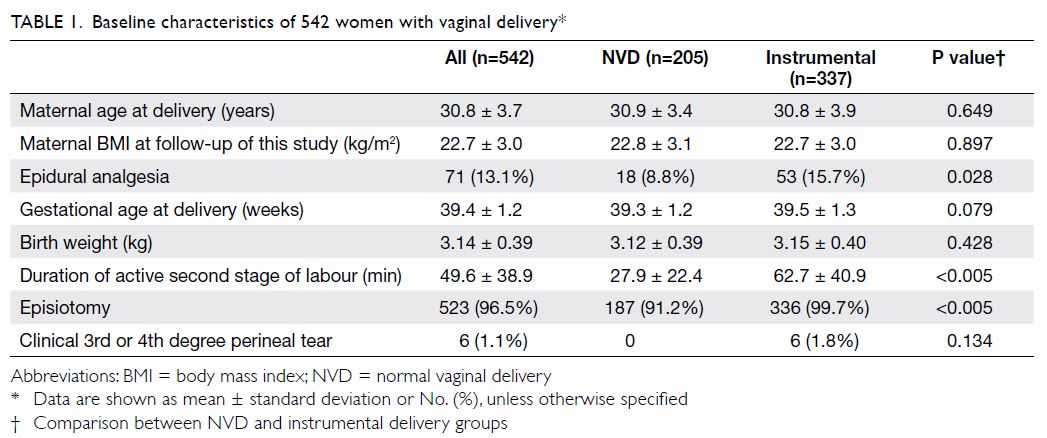

The demographic data and delivery information are

shown in Table 1. Left mediolateral episiotomy was performed

in 187 (91.2%) women in the normal vaginal delivery and 336 (99.7%) women

in the instrumental delivery group. The duration of active second stage

was longer in the instrumental delivery group than in the normal vaginal

delivery group (62.7 ± 40.9 min vs 27.9 ± 22.4 min, P<0.005), as a

prolonged second stage was the most common indication for instrumental

delivery in this cohort (48.4%). More women had epidural analgesia in the

instrumental delivery group than in the normal vaginal delivery group

(15.7% vs 8.8%, P=0.028). There was no significant difference between the

normal vaginal delivery and instrumental delivery groups regarding the

timing of endoanal US assessment (P=0.22).

Endoanal ultrasound findings and relationship of

obstetric anal sphincter injuries with delivery factors

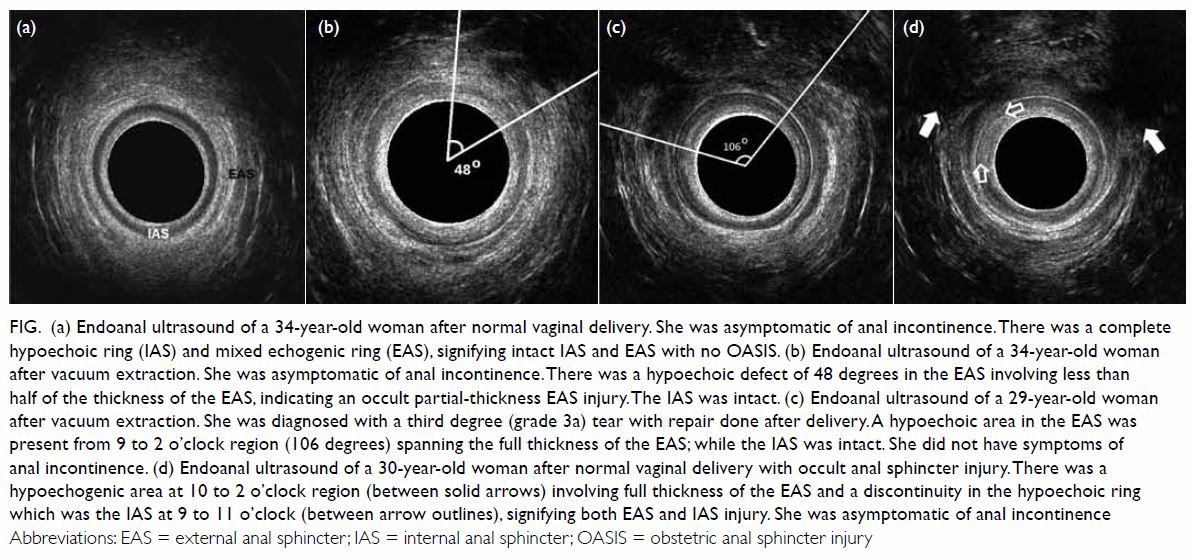

The Figure shows endoanal US images of intact anal

sphincters, as well as sphincters with different degrees of OASIS. There

were discrepancies or uncertainties in the endoanal US analysis of 16

women with respect to the diagnosis of OASIS. The two researchers

determined the diagnoses of these women by consensus review; six were

diagnosed with OASIS and 10 were regarded as normal.

Figure. (a) Endoanal ultrasound of a 34-year-old woman after normal vaginal delivery. She was asymptomatic of anal incontinence. There was a complete hypoechoic ring (IAS) and mixed echogenic ring (EAS), signifying intact IAS and EAS with no OASIS. (b) Endoanal ultrasound of a 34-year-old woman after vacuum extraction. She was asymptomatic of anal incontinence. There was a hypoechoic defect of 48 degrees in the EAS involving less than half of the thickness of the EAS, indicating an occult partial-thickness EAS injury. The IAS was intact. (c) Endoanal ultrasound of a 29-year-old woman after vacuum extraction. She was diagnosed with a third degree (grade 3a) tear with repair done after delivery. A hypoechoic area in the EAS was present from 9 to 2 o’clock region (106 degrees) spanning the full thickness of the EAS; while the IAS was intact. She did not have symptoms of anal incontinence. (d) Endoanal ultrasound of a 30-year-old woman after normal vaginal delivery with occult anal sphincter injury. There was a hypoechogenic area at 10 to 2 o’clock region (between solid arrows) involving full thickness of the EAS and a discontinuity in the hypoechoic ring which was the IAS at 9 to 11 o’clock (between arrow outlines), signifying both EAS and IAS injury. She was asymptomatic of anal incontinence

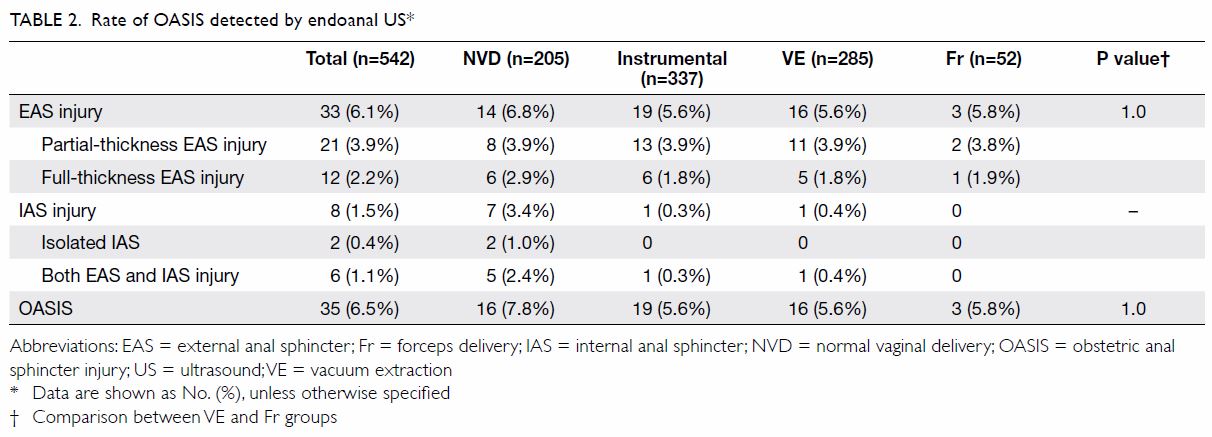

The prevalence of clinically detected OASIS was 0%

in the normal vaginal delivery group and 1.8% (n=6) in the instrumental

delivery group. Table 2 shows that the prevalence of OASIS detected

by endoanal US was 7.8% (n=16; 95% confidence interval [CI]=4.1%-11.5%) in

the normal vaginal delivery group and 5.6% (n=19; 95% CI=3.1%-8.1%) in the

instrumental delivery group (P=0.415). Twenty-nine (82.9%) women had

OASIS, as detected by endoanal US, that was not diagnosed during clinical

assessment immediately after delivery. Therefore, the occult OASIS rate

was 7.8% (95% CI=4.1%-11.5%) in the normal vaginal delivery group and 3.8%

(95% CI=1.8%-5.8%) in the instrumental delivery group. In addition, 63.6%

(n=21) of occult EAS injuries comprised partial-thickness EAS injuries,

whereas 36.4% (n=12) comprised full-thickness EAS injuries. When women

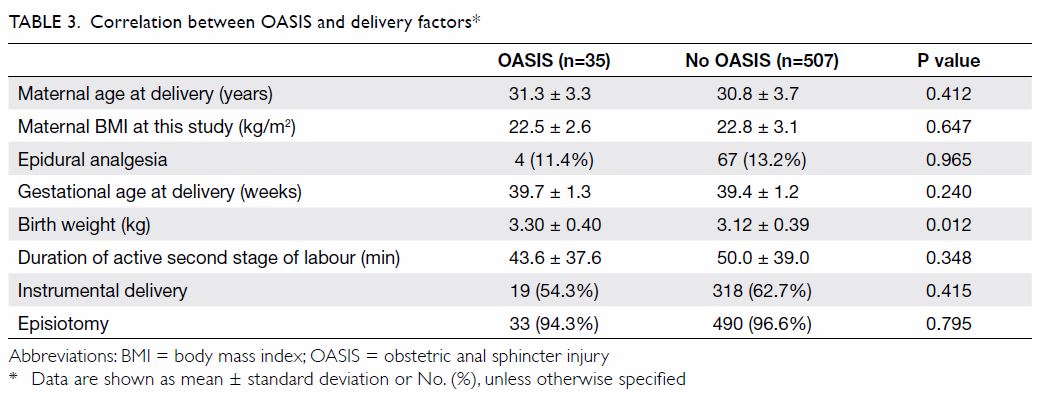

with OASIS were compared to those without OASIS, increased birth weight

was the only delivery factor associated with an increased risk of OASIS

(odds ratio [OR]=3.1, 95% CI=1.3%-7.6%, P=0.012) [Table 3].

Relationships of faecal and flatal incontinence

symptoms with obstetric anal sphincter injuries

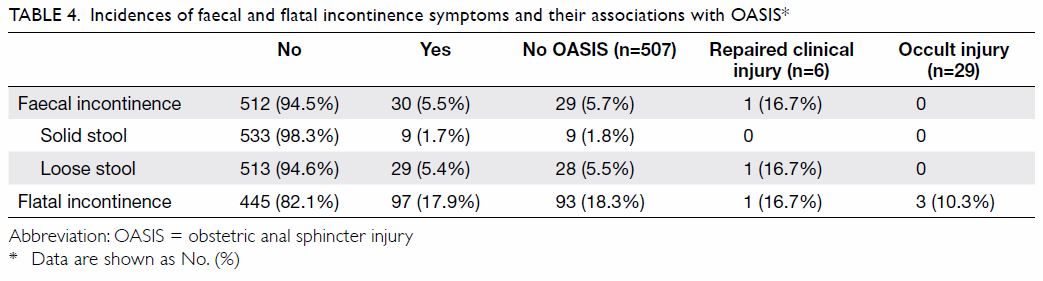

Overall, nine (1.7%) and 29 (5.4%) women reported

faecal incontinence to solid and loose stool, whereas 97 (17.9%) women

reported flatal incontinence (Table 4). All affected women reported mild symptoms.

Among the women with OASIS, only one (2.9%) with a repaired third degree

(3a) tear reported symptoms of both (faecal incontinence to loose stool

and flatal incontinence). Three women (10.3%) who had occult injury

reported flatal incontinence. There were no associations between the

presence of OASIS and faecal incontinence (P=0.71) or between the presence

of OASIS and flatal incontinence (P=0.37).

Discussion

Primiparity has been associated with increased

risks of OASIS (ORs of 2.39 and 8.34) in large retrospective studies.19 20 In the

present study, which included large number of primiparous women, the

findings on endoanal US were compared with women’s reported symptoms of

faecal and flatal incontinence. Importantly, there were no associations

between faecal or flatal incontinence and the presence of OASIS.

After assessment by endoanal US, the prevalence of

OASIS in the normal vaginal delivery group increased from 0% to 7.8% and

that in the instrumental delivery group increased from 1.8% to 5.6%.

Overall, 82.9% of women with OASIS detected by endoanal US had not been

diagnosed with OASIS during clinical assessment immediately after

delivery. This finding is consistent with the results of the study by

Andrews et al.9 In that study, the

prevalence of OASIS markedly increased from 11% to 24.5% when women were

re-examined by an experienced research fellow; 87% of OASIS diagnoses were

missed by midwives and 28% were missed by junior doctors.9 In our study, normal vaginal deliveries were primarily

attended by midwives, whereas instrumental deliveries were performed by

residents. The higher rate of occult OASIS in the normal vaginal delivery

group suggests that midwives currently receive inadequate training for

clinical identification of OASIS. Thus, to improve the detection of OASIS,

midwives and doctors should be trained to recognise OASIS by performing a

standardised vaginal and rectal examination after delivery.

Compared with previous studies, the rate of OASIS

determined by endoanal US in our study (6.5%) was lower than the rate of

10% determined by a single examiner in a prospective observational study

conducted in the same unit.6 This

could be a result of the small sample size (70 subjects) in the prior

study. Furthermore, most patients with OASIS (5/7) in that study were

reported to have small 3a tears. There were no 3c or fourth-degree tears

in that study. Following the same delivery practices, clinically detected

small 3a tears may therefore appear normal in endoanal US. Furthermore,

these tears might not result in long-term consequences.6 21

The finding of an overall lower OASIS rate in Hong

Kong, compared with that in Asian women who deliver in Caucasian

countries, is not new.6 Asian women

who deliver in locations with more restrictive policies regarding

episiotomy have shown higher rates of OASIS.22

23 24

In a study conducted in the United States, OASIS was found significantly

more frequently in Asian women than in women of other ethnicities.23 In Australia, nulliparous women born in South Asia

and South-East Asia were 2.6-fold and 2.1-fold more likely to exhibit

OASIS than women born in Australia or New Zealand women.24 It is uncertain whether the increased rate of

episiotomy might protect against OASIS in Asian women and contribute to

the relative reduction in the rate of OASIS in Hong Kong. Thus, our unit

is currently conducting a randomised controlled trial to compare

restrictive and routine episiotomy. In addition to episiotomy, the

delivery technique and hands-on approach might contribute to the relative

reduction in the rate of OASIS. All deliveries in our study were conducted

with women in a lithotomy position, with their feet on footplates or in

stirrups. All midwives and doctors conducting the deliveries used hands-on

techniques to protect the perineum in each woman. Either firm pressure or

pressure with squeezing of the perineum, also known as the modified Ritgen

manoeuvre, was used.6 Warm

compresses were not commonly used by midwives and doctors in our study.

The OASIS rate in the normal vaginal delivery group

was higher than that in the the instrumental delivery group, but this

difference was not statistically significant. The majority of deliveries

by women in the instrumental delivery group were performed using vacuum

extraction. The rate of OASIS in these women could be similar to that of

women in the normal vaginal delivery group. The OASIS rates were similar

in women who delivered with the aid of vacuum extraction or with forceps,

whereas previous studies showed that forceps delivery was associated with

an increased risk of OASIS.19 20 25

The small number of forceps deliveries in this study might have led to

insufficient statistical power to detect a difference between the two

types of instrumental deliveries. Furthermore, the use of forceps was

primarily restricted to patients who were low risk, and mostly comprised

outlet/low-cavity forceps deliveries. Previous studies reported that

macrosomia, higher birth weight (OR=1.14, 95% CI=1.0-1.3, P=0.039), and

shorter perineal length were risk factors for OASIS.6 19 20 The present study had similar findings, in that

higher birth weight was a risk factor for OASIS (OR=3.1, 95% CI=1.3-7.6,

P=0.012). However, perineal length was not assessed, which is an important

limitation of this study.

Flatal incontinence was present in 17.9% of women

after delivery, which is comparable to the rate reported in previous

studies.26 27 In addition to OASIS, irritable bowel syndrome, high

body mass index, and mode of delivery constitute factors associated with

flatal incontinence.20 21 Overall, 5.5% of women reported faecal incontinence;

most of these women reported faecal incontinence to loose stool and mild

symptoms only. Most obstetric anal sphincter injuries were not detected

during clinical examination. Shortly after delivery, the presence of OASIS

was not associated with symptoms of faecal or flatal incontinence, but a

longer-term study is needed to confirm these findings. However, we

previously found that only antenatal faecal incontinence symptoms

increased the likelihood of faecal incontinence at 12 months after

delivery (OR=6.1, 95% CI=1.8-21.5, P=0.005), whereas maternal

characteristics, mode of delivery, and the presence of OASIS did not.28 In longer-term follow-up (3-5 years after delivery),

2.1% and 5.9% of women who had one vaginal delivery reported faecal

incontinence to solid and loose stool, respectively.29

To the best of our knowledge, there have been no

randomised controlled trials regarding the optimal timing for the use of

endoanal US to assess OASIS after vaginal delivery. One randomised

controlled trial has been conducted to compare clinical examination alone

(control group) and clinical examination with additional endoanal US

immediately after delivery (intervention group).30

31 The results of that study

showed that US performed immediately after delivery—before repair—might

detect more cases of OASIS: 5.6% of women were found to have

full-thickness OASIS that was not recognised during clinical examination

alone.31 However, the study also

showed that five of 21 women underwent unnecessary intervention, as the

sonographic defect could not be clinically located, despite surgical

exploration.31 Therefore, the use

of endoanal US immediately after delivery and before repair was not

recommended.

Women with OASIS should undergo follow-up after

delivery to assess symptoms of faecal incontinence. Currently, there is no

consensus regarding the optimal mode of delivery for these women in

subsequent pregnancies. Scheer et al32

and Karmarkar et al33 assessed

women who had OASIS in subsequent pregnancies using a questionnaire,

endoanal US, and manometry. Vaginal delivery was recommended for

asymptomatic women with normal findings. Women were reassessed after

subsequent deliveries. There were no statistically significant differences

in anal manometry findings, anal symptoms, or quality of life following

subsequent vaginal delivery or caesarean section.32

33 In the study by Scheer et al,32 new OASIS occurred in only one

woman after a vaginal delivery. Therefore, decisions regarding the mode of

delivery for subsequent pregnancies after OASIS should be based on

clinical symptoms, anal manometry, and endoanal US. This would help to

preserve anal sphincter function and avoid unnecessary caesarean sections.

Currently, the value of the above assessments is limited in Hong Kong. The

significance of an incidental finding of occult anal sphincter defect

remains uncertain.

Conclusion

The prevalence of OASIS determined by endoanal US

was higher than the rate determined by clinical practice. This may

indicate that additional training for midwives and doctors may be required

to improve the detection of OASIS. At 6 to 12 months after delivery, OASIS

was not associated with symptoms of faecal or flatal incontinence, but a

longer-term study is needed to confirm these findings.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Concept or design of the study: RYK Cheung, SSC

Chan.

Acquisition of data: OYK Wan, RYK Cheung, LL Lee, SSC Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: SPK Kwok, SSC Chan.

Drafting of the article: All authors.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: SPK Kwok, OYK Wan, RYK Cheung, SSC Chan.

Acquisition of data: OYK Wan, RYK Cheung, LL Lee, SSC Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: SPK Kwok, SSC Chan.

Drafting of the article: All authors.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: SPK Kwok, OYK Wan, RYK Cheung, SSC Chan.

Declaration

The results from this research have been presented,

in part, at the following conferences:

1. Wan OYK, Cheung RYK, Chan SSC. 6th Annual Meeting of the Asia-Pacific Urogynecology Association and 13th Japanese Society of Pelvic Organ Prolapse Surgery Joint Conference–Young Doctors Session. Okinawa, Japan, 22-24 March 2019 (oral abstract presentation).

2. Wan OYK, Kwok SPK, Cheung RYK, Chan SSC. Hospital Authority Convention 2019, Hong Kong, 14-15 May 2019 (e-poster presentation).

3. Kwok SPK, Wan OYK, Cheung RYK, Lee LL, Chung JPW, Chan SSC. Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society of Hong Kong Annual Scientific Meeting 2019, Hong Kong, 1-2 June 2019 (oral presentation).

1. Wan OYK, Cheung RYK, Chan SSC. 6th Annual Meeting of the Asia-Pacific Urogynecology Association and 13th Japanese Society of Pelvic Organ Prolapse Surgery Joint Conference–Young Doctors Session. Okinawa, Japan, 22-24 March 2019 (oral abstract presentation).

2. Wan OYK, Kwok SPK, Cheung RYK, Chan SSC. Hospital Authority Convention 2019, Hong Kong, 14-15 May 2019 (e-poster presentation).

3. Kwok SPK, Wan OYK, Cheung RYK, Lee LL, Chung JPW, Chan SSC. Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society of Hong Kong Annual Scientific Meeting 2019, Hong Kong, 1-2 June 2019 (oral presentation).

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, JPW Chung was not

involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no

conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from local institute,

The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster

Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Ref CRE-2013.332). Written informed

consent was obtained from all participants.

References

1. Fenner DE, Genberg B, Brahma P, Marek L,

DeLancey JO. Fecal and urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery with

anal sphincter disruption in an obstetrics unit in the United States. Am J

Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:1543-50. Crossref

2. Thiagamoorthy G, Johnson A, Thakar R,

Sultan AH. National survey of perineal trauma and its subsequent

management in the United Kingdom. Int Urogynecol J 2014;25:1621-7. Crossref

3. Baghestan E, Irgens LM, Børdahl PE,

Rasmussen S. Trends in risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injuries

in Norway. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:25-34. Crossref

4. Ekéus C, Nilsson E, Gottvall K.

Increasing incidence of anal sphincter tears among primiparas in Sweden: a

population-based register study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008;87:564-73.

Crossref

5. Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists. Territory-wide audit in Obstetrics & Gynaecology;

2009.

6. Bates LJ, Melon J, Turner R, Chan SS,

Karantanis E. Prospective comparison of obstetric anal sphincter injury

incidence between an Asian and Western hospital. Int Urogynecol J

2019;30:429-37. Crossref

7. Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for

vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(1):CD000081. Crossref

8. Cheung RY, Shek KL, Chan SS, Chung TK,

Dietz HP. Pelvic floor muscle biometry and pelvic organ mobility in East

Asian and Caucasian nulliparae. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;45:599-604.

Crossref

9. Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Jones

PW. Occult anal sphincter injuries—myth or reality? BJOG 2006;113:195-200.

Crossref

10. Guzmán Rojas RA, Shek KL, Langer SM,

Dietz HP. Prevalence of anal sphincter injury in primiparous women.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013;42:461-6. Crossref

11. Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Thomas

JM, Bartram CI. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl

J Med 1993;329:1905-11. Crossref

12. Chan SS, Cheung RY, Yiu KW, Lee LL,

Leung TY, Chung TK. Pelvic floor biometry during first singleton pregnancy

and the relationship with symptoms of pelvic floor disorders: a

prospective observational study. BJOG 2014;121:121-9. Crossref

13. Chan SS, Cheung RY, Yiu KW, Lee LL,

Chung TK. Pelvic floor biometry in Chinese primiparous women 1 year after

delivery: a prospective observational study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol

2014;43:466-74. Crossref

14. Chung MY, Wan OY, Cheung RY, Chung TK,

Chan SS. Prevalence of levator ani muscle injury and health-related

quality of life in primiparous Chinese women after instrumental delivery.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;45:728-33. Crossref

15. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock

SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening

the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement:

guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol

2008;61:344-9. Crossref

16. Sultan AH. Obstetric perineal injury

and anal incontinence. Clinical Risk 1999;5:193-6. Crossref

17. Chan SS, Cheung RY, Yiu AK, et al.

Chinese validation of Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor

Impact Questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J 2011;22:1305-12. Crossref

18. Roos AM, Thakar R, Sultan A. Outcome

of primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS): does the

grade of tear matter? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010;36:368-74. Crossref

19. de Leeuw JW, Struijk PC, Vierhout ME,

Wallenburg HC. Risk factors for third degree perineal ruptures during

delivery. BJOG 2001;108:383-7. Crossref

20. Aukee P, Sundström H, Kairaluoma MV.

The role of mediolateral episiotomy during labour: analysis of risk

factors for obstetric anal sphincter tears. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand

2006;85:856-60. Crossref

21. Ramalingam K, Monga AK. Outcomes and

follow-up after obstetric anal sphincter injuries. Int Urogynecol J

2013;24:1495-500. Crossref

22. Hauck YL, Lewis L, Nathan EA, White C,

Doherty DA. Risk factors for severe perineal trauma during vaginal

childbirth: a Western Australian retrospective cohort study. Women Birth

2015;28:16-20. Crossref

23. Grobman WA, Bailit JL, Rice MM, et al.

Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and obstetric care.

Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:1460-7. Crossref

24. Davies-Tuck M, Biro MA, Mockler J,

Stewart L, Wallace EM, East C. Maternal Asian ethnicity and the risk of

anal sphincter injury. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015;94:308-15.Crossref

25. Stedenfeldt M, Øian P, Gissler M, Blix

E, Pirhonen J. Risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injury after a

successful multicentre interventional programme. BJOG 2014;121:83-91. Crossref

26. Boreham MK, Richter HE, Kenton KS, et

al. Anal incontinence in women presenting for gynecologic care:

prevalence, risk factors, and impact upon quality of life. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2005;192:1637-42. Crossref

27. Melville JL, Fan MY, Newton K, Fenner

D. Fecal incontinence in US women: a population-based study. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2005;193:2071-6. Crossref

28. Chan SS, Cheung RY, Yiu KW, Lee LL,

Chung TK. Prevalence of urinary and fecal incontinence in Chinese women

during and after first pregnancy. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24:1473-9. Crossref

29. Ng K, Cheung RY, Lee LL, Chung TK,

Chan SS. An observational follow-up study on pelvic floor disorders to 3-5

years after delivery. Int Urogynecol J 2017;28:1393-9. Crossref

30. Walsh KA, Grivell RM. Use of endoanal

ultrasound for reducing the risk of complications related to anal

sphincter injury after vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2015;(10):CD010826. Crossref

31. Faltin DL, Boulvain M, Floris LA,

Irion O. Diagnosis of anal sphincter tears to prevent fecal incontinence:

a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:6-13. Crossref

32. Scheer I, Thakar R, Sultan AH. Mode of

delivery after previous obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS)—a

reappraisal? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2009;20:1095-101. Crossref

33. Karmarkar R, Bhide A, Digesu A,

Khullar V, Fernando R. Mode of delivery after obstetric anal sphincter

injury. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2015;194:7-10. Crossref