Hong Kong Med J 2025;31:Epub 24 Jan 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PERSPECTIVE

Incorporating the cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic

health framework into the local healthcare system: a position statement from the Hong Kong College of Physicians

CH Lee, MB, BS, MD1; G Tan, MBChB2; Sydney CW Tang, MB, BS, MD3 #; YW Ng, MBChB4 #; Michael KY Lee, MB, BS5 #; Johnny WM Chan, MB, BS6 #; TM Chan, MB, BS, DSc7 #

1 Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

6 Division of Respiratory Medicine, Department of Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

7 Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

# Steering Committee of the Hong Kong College of Physicians position statement

Corresponding authors: Prof Sydney CW Tang (scwtang@hku.hk), Prof TM Chan (dtmchan@hku.hk)

Introduction

What is cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic

syndrome?

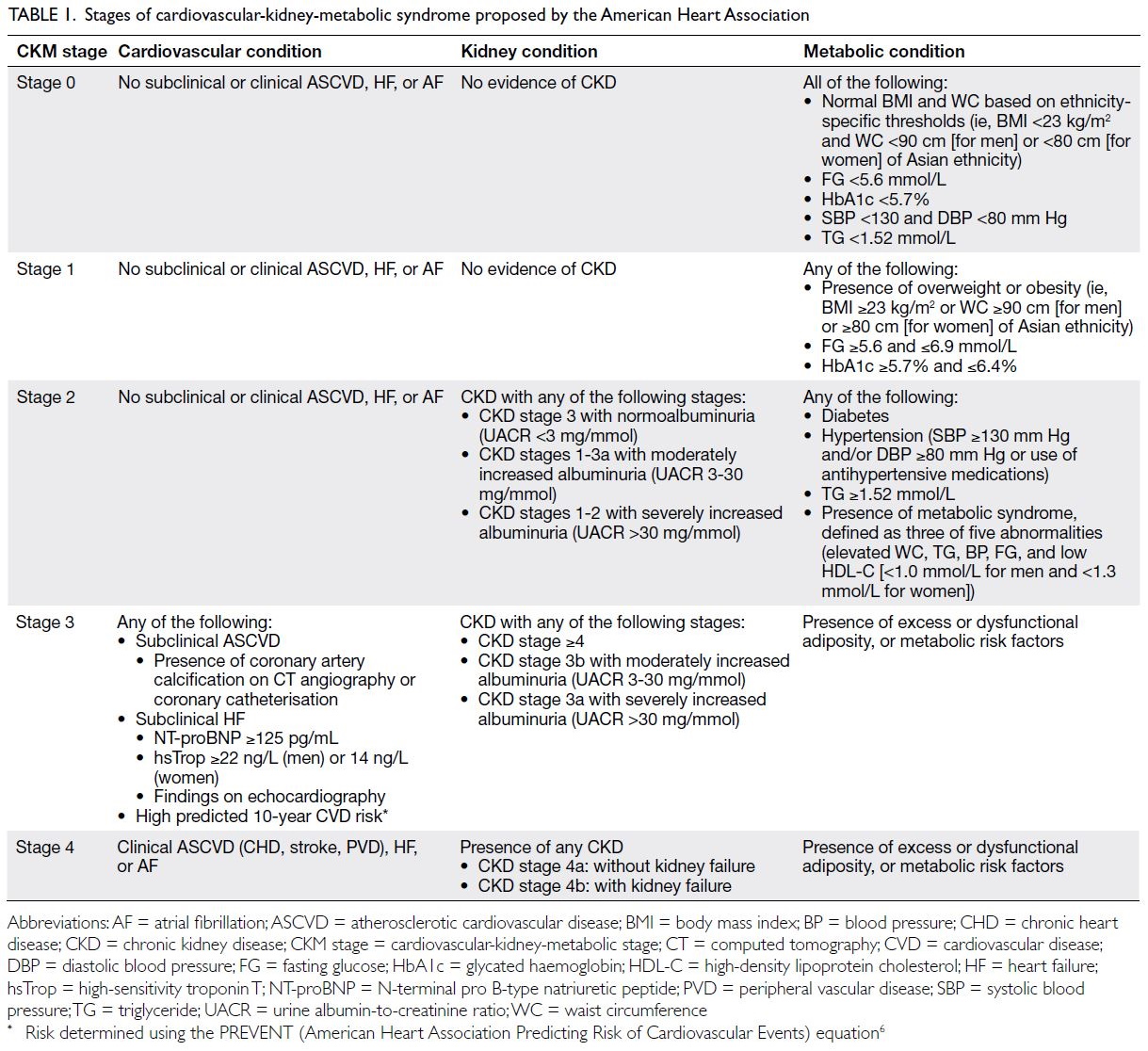

Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome

is a new entity that emphasises interconnections

among atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

(ASCVD), atrial fibrillation (AF), heart failure

(HF), chronic kidney disease (CKD), excess

adiposity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes.1 It is

categorised into five stages (Table 1), reflecting the

progressive nature of the pathophysiology behind

this multifaceted syndrome and the increasing risk

of adverse cardiovascular outcomes associated with

higher CKM stages.2 3 4 5 6 The CKM health framework

incorporates screening, staging, and management

for early identification of potential CKM-related

events.7 8

Table 1. Stages of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome proposed by the American Heart Association

Adaptation of the CKM model is influenced by

access, financing, and care delivery. A multispecialty

working group of the Hong Kong College of

Physicians (HKCP) developed this Position

Statement concerning incorporation of the CKM

health framework into the local healthcare system,

taking into consideration local healthcare needs,

existing resources and limitations, as well as future

healthcare directions and initiatives in Hong Kong.

Patient care challenges in real-world settings

The CKM concept aims to identify individuals at risk for suboptimal CKM health to enable

timely intervention and slow disease progression.

Optimal care delivery remains challenging despite

improvements in local health literacy. A recent

local population health survey revealed that many

individuals were unaware of overweight or obesity

status, as well as hypertension, diabetes, and elevated

cholesterol.9

The ageing local population (~21% of

individuals are aged ≥65 years10) further strains

healthcare resources due to increasing numbers

of patients with CKM risks, as well as end-organ

damage. A lack of public awareness about CKM

health and limitations in primary healthcare

constitute barriers to implementing the CKM health

framework.

The Hospital Authority has largely focused on

specialist care, while our primary healthcare system

is comparatively underdeveloped.11 Public health expenditures reflect this focus.12 The Health Bureau’s

Primary Healthcare Blueprint (2022) and the 3-year

Chronic Disease Co-Care (CDCC) Pilot Scheme

are promising initiatives, but their integration with

specialist care remains unclear.

Screening

Screening asymptomatic individuals for metabolic

risk factors (eg, overweight/obesity, central adiposity,

dysglycaemia, hypertension, and dyslipidaemia) is

a key component of the CKM health framework. For adults aged ≥21 years, this includes annual

measurements of body mass index (BMI) and waist

circumference, along with periodic assessments

of blood pressure (BP), lipid levels, and glycaemic

status. Screening intervals depend on CKM stage:

every 3-5 years for CKM stage 0 (healthy and lean),

every 2-3 years for CKM stage 1 (overweight/obese

or prediabetes), and annually for CKM stage 2

(diabetes, hypertension, or hypertriglyceridaemia).1

These recommendations align with the American

Diabetes Association’s guidance that asymptomatic

adults aged ≥35 years, or overweight/obese adults

with risk factors—such as physical inactivity, family

history of diabetes, hypertension, high triglyceride levels, or polycystic ovarian syndrome—undergo

screening for prediabetes or diabetes every 3

years if no abnormalities are detected.13 The need

for triglyceride screening remains unclear, and

discussions continue regarding BMI thresholds for

overweight/obesity in Asian populations.14

The CDCC Pilot Scheme, launched by the

Hong Kong SAR Government in November 2023,

offers subsidised screening in the private sector for

residents aged ≥45 years without known diabetes or

hypertension.15 Initial assessments include BP and

glycated haemoglobin), with follow-up tests (lipid

profile, estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR],

urinalysis) if hypertension or diabetes is detected. Blood pressure thresholds for hypertension vary

across guidelines.16 17 The HKCP previously endorsed

defining hypertension as BP ≥140/90 mmHg18;

the CKM framework utilises a lower threshold

of 130/80 mmHg based on recent evidence.

Home BP monitoring and standardised office BP

measurements are both acceptable. Early detection of

CKM risk factors aligns with the Primary Healthcare

Blueprint,19 which promotes chronic disease

prevention through a family-centric, community-based

primary care system. A key concept, “family

doctor for all,” aims to enhance public access to care,

including screening and diagnosis of prediabetes,

early diabetes, and hypertension via coordination

with family doctors in the Primary Care Register.

Timely screening and intervention can reduce

complications such as CKD, cardiovascular disease

(CVD), and hospitalisations.

Roles of physician specialists and primary

care doctors in the cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic

health framework

The increasing incidence of kidney failure and

growing healthcare burden of CKD, which now

affects 10% of the global population, have made

CKD an international health priority. Nephrologists

play a central role in managing individuals across

CKM stages. Chronic kidney disease substantially

increases risks of cardiovascular morbidity and

mortality; many patients, especially those aged ≥75

years, die of CVD before exhibiting kidney failure

or requiring dialysis.20 Among dialysis patients

in Hong Kong, CVD and stroke caused 30.3% of

deaths in 2022.21 Diabetes or hypertension was the

primary diagnosis for 63% of patients initiating

kidney replacement therapy. Early CKD detection,

particularly in at-risk individuals, allows preventive

measures during asymptomatic stages. Primary care

doctors are needed to identify and manage these

individuals.

Cardiovascular risk factors, including CKD,

often remain unrecognised until disease becomes

clinically apparent. The CKM staging system

prioritises early detection of cardiovascular risk

factors, recommending eGFR and urine albumin-to-creatinine

ratio assessments for at-risk individuals,

such as those with hypertriglyceridaemia, metabolic

syndrome, diabetes, hypertension (stage ≥2), or

clinical CVD. Indeed, evaluation of albuminuria

should also be considered in CKM stage 1,

characterised by obesity or dysfunctional adiposity,

which manifests as prediabetes—both risk factors

for CKD.22 23 These recommendations aim to

improve kidney health awareness and promote

CKD screening among primary care doctors, family

physicians, and specialists, who are often the first to

encounter patients in early stages of CKM.

The Predicting Risk of CVD Events (PREVENT) equation from the American Heart

Association is recommended to assess 10-year CVD

risk in asymptomatic individuals without ASCVD

or HF. This tool estimates overall CVD risk and

guides preventive therapy initiation.6 Caution is

needed because the equation may overestimate risk

in individuals of Asian descent.24 25 The PREVENT

equation is preferred over the Pooled Cohort

Equations26 in the CKM framework27 because it

includes CKM-specific factors that constitute novel

CVD risk factors. Although the social deprivation

index is specific to the United States, the inclusion

of socioeconomic background during CVD risk

estimation is relevant in Hong Kong. The risk score

can be calculated using the online tool provided by

the American Heart Association.28 The PREVENT

equation, designed for primary prevention in

individuals aged 30-79 years without coronary heart

disease, stroke, or HF, helps tailor patient-centred

preventive therapies according to guidelines.26 29

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) testing is

recommended for further CVD risk stratification and

statin use guidance during primary prevention.26 27

However, routine CAC testing is not advised in

Hong Kong for CKM screening or staging due to

concerns about increased downstream testing and

the lack of a structured follow-up programme. When

CAC results are available, even for asymptomatic

individuals, they should inform CKM staging and

guide therapies following established guidelines.26 27 29

The CKM framework proposes testing for

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP),27 N-terminal

pro-BNP, or high-sensitivity troponin in at-risk

individuals to detect subclinical HF.27 Although two

randomised studies demonstrated the utility of this

approach for guiding renin-angiotensin-aldosterone

system-modifying agent therapy,30 31 routine cardiac

biomarker testing in asymptomatic individuals is

not recommended within Hong Kong. Angiotensin-converting

enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) are already

recommended as first-line therapy, particularly for

patients with diabetes,32 and local cost-effectiveness

data are unavailable. Furthermore, it can be

challenging to interpret BNP, N-terminal pro-BNP,

and troponin levels in moderate to advanced CKD

(a component of CKM syndrome) due to renal

excretion of these biomarkers. When available,

cardiac biomarker data should be considered

for management of HF medications with proven

benefits, even in asymptomatic individuals.33

Prevention of complications

The CKM health framework prioritises identifying

and treating CKM risk factors during the preclinical

phase to prevent clinical ASCVD, AF, HF, and

kidney failure. Locally, patients with hypertension

and diabetes in General Out-patient Clinics undergo

regular screening for complications through the RAMP (Risk Assessment and Management

Programs) for Hypertension and Diabetes,

respectively.34 35 Patients with diabetes in public

hospital clinics also undergo regular complications

screening, including cardiovascular risk assessments,

urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio testing, and, in

some centres, vascular Doppler studies.34 35 In the

private sector, the Health Bureau of Hong Kong has

established Reference Frameworks36 37 for diabetes

and hypertension care, highlighting the importance

of regular diabetic complications screening.

The incidences of CKD, metabolic diseases,

and obesity are rising, even in younger individuals;

greater emphasis on CKD prevention is needed,

particularly regarding screening methods and

timing. The CKM framework recommends CKD

screening before age 21 among individuals with

risk factors such as obesity, hypertriglyceridaemia,

diabetes, or hypertension. Although not widely

adopted locally, the HKCP supports earlier CKD

detection to improve kidney survival and quality

of life.38 Screening gaps exist for albuminuria in

high-risk groups, including overweight or obese

individuals and those with clinical CVD.

Because most patients in early stages of CKM

are asymptomatic, primary care and family doctors

play a central role in ensuring regular follow-up.

This role includes monitoring glycaemic status, lipid

profiles, and BP, along with surveillance for CKM

complications, such as CKD progression or clinical

CVD.

Clinical management: an interdisciplinary

care model in Hong Kong

The HKCP supports the guideline-directed

management approach in the CKM health

framework, although anthropometric thresholds

for interventions slightly differ due to population

variations. The BMI threshold for metabolic and

bariatric surgery was recently updated to ≥27.5 kg/m2

for Asian populations.39 This threshold also applies

the use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists

(GLP1RAs) for obesity treatment in patients with

type 2 diabetes, aligning with the World Health

Organization’s recommended BMI action point

for high-risk individuals in Asian populations.40 If

pharmacotherapy cost constraints are addressed,

the threshold could be lowered to ≥25 kg/m2, as

indicated in some Asian guidelines.41 In Hong

Kong, access to newer CKM pharmacotherapies is

limited. Among GLP1RAs approved for managing

obesity in individuals without diabetes, only daily

liraglutide is currently available, whereas weekly

semaglutide is not. Icosapent ethyl, an omega-3

fatty acid treatment for hypertriglyceridaemia,

is unavailable in the public sector. The CKM

framework recommends initiating cardioprotective antidiabetic agents regardless of glycaemic control,

even before metformin in individuals with glycated

haemoglobin level <7.5%. However, affordability and

patient preferences may impact implementation.

Glycaemic control optimisation remains essential

because early and effective control improves

cardiorenal outcomes and reduces mortality.42

Notably, statin pharmacokinetics differ between

Chinese and Western populations43 44; rosuvastatin

dosages should not exceed 20 mg daily in Chinese

individuals due to rhabdomyolysis risk.

In CKM stage 4 (established CVD), recurrent

cardiovascular event risk is high, but many patients fail

to achieve the recommended low-density lipoprotein

cholesterol target of <1.8 mmol/L.45 Identification

of high-risk individuals and intensification of

lipid-lowering therapy with high-intensity statins,

ezetimibe, and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors are needed to achieve

therapeutic goals.26 In patients with HF, particularly

those exhibiting reduced left ventricular ejection

fraction, guideline-directed medical therapy

(GDMT) classes—beta-blockers, angiotensin

receptor blockers (ARBs)/neprilysin inhibitors,

sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors, and

mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists—should

be initiated and titrated appropriately.33 Among

patients with AF exhibiting CKM syndrome and

stroke risk factors, anticoagulation is advised.46 Co-morbidities

such as severe obesity and CKD should

be carefully considered because they may influence

direct oral anticoagulant efficacy.

Patients across all CKD and CVD stages47

should be evaluated for kidney-protective therapies,

many of which also provide cardiovascular benefits.

These include ACEi or ARBs, sodium-glucose

co-transporter 2 inhibitors, GLP1RAs, and the

nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist

finerenone, as appropriate. Most patients should

receive an ACEi or ARB at the maximum tolerated

dose, with additional agents introduced based on

individual needs and tolerability. Goals include

optimising BP, reducing albuminuria, stabilising

eGFR, and lowering cardiovascular risk. Some

therapies may cause short-term haemodynamic

effects on kidney function or adverse effects, leading

to premature discontinuation. The CKM framework

emphasises initiation and maintenance of these

therapies. The HKCP supports their timely uptake

and continued use by specialists and primary care

physicians.

Implementation of the CKM health

framework in Hong Kong faces challenges, including

discrepancies in drug formularies between primary

care and specialty clinics and inadequate coordination

between these services. Patients are sometimes

referred to specialty clinics solely for medications

unavailable in primary care. Such referral increases waiting times at overburdened specialty clinics and

delays GDMT initiation. Follow-up intervals may

be extended due to heavy patient loads, impacting

treatment adherence and monitoring. The CDCC

Pilot Scheme provides targeted subsidies to support

the diagnosis and management of chronic diseases,

particularly hypertension and diabetes, in the

private sector. This co-care model aims to benefit

patients across various CKM stages and mitigate

complications.

Conclusions and the way forward

Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome has

substantial implications for patients and society.

The HKCP emphasises the need for collaborative

interdisciplinary care within the CKM healthcare

framework, integrating primary care, specialist

care, and medical subspecialties to prevent

complications and protect organs. Although GDMT

ensures evidence-based care, clinicians must tailor

management to the unique characteristics of each

patient, addressing gaps in trial data and local

applicability. Conditions such as hyperglycaemia, dyslipidaemia, obesity, kidney insufficiency, and

hypertension should not be viewed as “risk factors”

but as chronic conditions requiring early intervention

to prevent CVD and CKD. Kidney health is central

to CKM syndrome, given the high prevalence of

kidney failure among patients with diabetes or CVD.

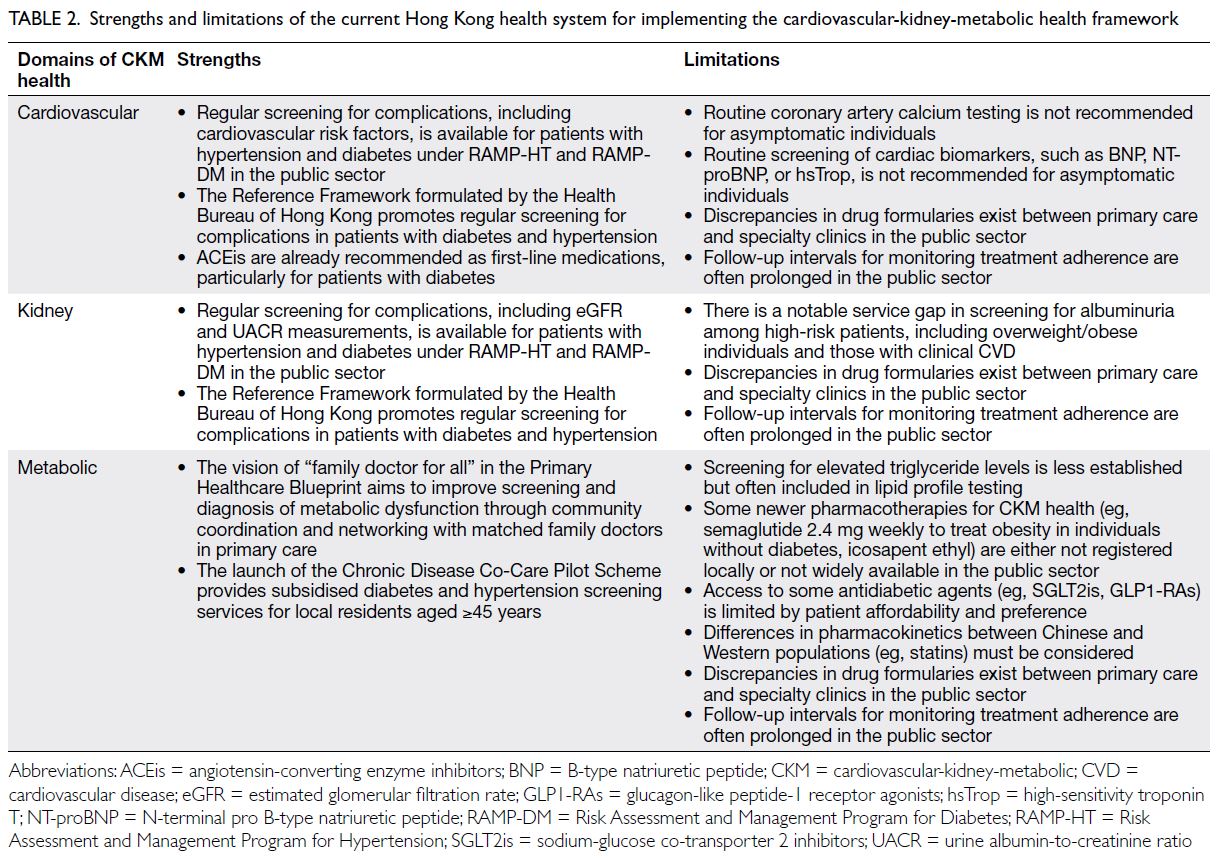

Considering the strengths and limitations

of the local healthcare system (Table 2), multiple

actions are needed to mitigate the increasing impact

of CKM syndrome. The public and healthcare

professionals must be educated regarding its

adverse effects and access to effective interventions.

Integrated care across primary and specialist

services is essential, supported by healthcare policy

focusing on organ protection to ensure coordination,

minimise duplication, and optimise resource use. A

collaborative care model involving all stakeholders

and providers is essential. The HKCP hopes

this position statement will raise awareness and

prompt timely strategies to address the growing

challenges of CKM syndrome, ultimately improving

cardiovascular, metabolic, and kidney health in the

community.

Table 2. Strengths and limitations of the current Hong Kong health system for implementing the cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic health framework

Author contributions

Concept or design: SCW Tang and TM Chan.

Acquisition of data: CHL, G Tan and SCW Tang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CHL, G Tan, SCW Tang and TM Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: CHL, G Tan and SCW Tang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: CHL, G Tan and SCW Tang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: CHL, G Tan, SCW Tang and TM Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: CHL, G Tan and SCW Tang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

CH Lee has received advisory board and lecture honoraria

from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly,

Gilead, GSK, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi Aventis. SCW Tang

has reported consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim,

Novartis, and Travere Therapeutics, as well as speaker fees

from AstraZeneca, Baxter, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim/Eli Lilly, GSK, and Novartis. The other co-authors have no

competing interests relevant to this manuscript.

Funding/support

This position statement was not supported by any specific

grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or

not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Ndumele CE, Rangaswami J, Chow SL, et al. Cardiovascularkidney-

metabolic health: a presidential advisory from the

American Heart Association. Circulation 2023;148:1606-35. Crossref

2. Fox CS, Matsushita K, Woodward M, et al. Associations

of kidney disease measures with mortality and end-stage

renal disease in individuals with and without diabetes: a

meta-analysis. Lancet 2012;380:1662-73. Crossref

3. Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors for Chronic

Diseases Collaboration (BMI Mediated Effects); Lu Y,

Hajifathalian K, et al. Metabolic mediators of the effects

of body-mass index, overweight, and obesity on coronary

heart disease and stroke: a pooled analysis of 97 prospective

cohorts with 1.8 million participants. Lancet 2014;383:970-83. Crossref

4. Shah AD, Langenberg C, Rapsomaniki E, et al. Type 2

diabetes and incidence of cardiovascular diseases: a cohort

study in 1.9 million people. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol

2015;3:105-13. Crossref

5. Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, et al. Obesity and

cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the

American Heart Association. Circulation 2021;143:e984-1010. Crossref

6. Khan SS, Coresh J, Pencina MJ, et al. Novel prediction

equations for absolute risk assessment of total

cardiovascular disease incorporating cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic health: a scientific statement from the

American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;148:1982-2004. Crossref

7. Nuffield Department of Population Health Renal Studies

Group; SGLT2 inhibitor Meta-Analysis Cardio-Renal

Trialists’ Consortium. Impact of diabetes on the effects

of sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors on kidney outcomes: collaborative meta-analysis of large placebo-controlled

trials. Lancet 2022;400:1788-801. Crossref

8. Sattar N, Lee MM, Kristensen SL, et al. Cardiovascular,

mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor

agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic

review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet

Diabetes Endocrinol 2021;9:653-62. Crossref

9. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health,

HKSAR Government. Report of Population Health Survey

2020-22. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/dh_phs_2020-22_part_2_report_eng_rectified.pdf. Accessed 19 Apr 2023.

10. Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government. Statistics:

major health related statistics of Hong Kong. Available

from: https://www.healthbureau.gov.hk/statistics/en/health_statistics.htm. Accessed 20 Dec 2024.

11. Pang FC, Lai SS. Establishment of the primary healthcare

commission. Hong Kong Med J 2023;29:6-7. Crossref

12. Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government. Hong

Kong’s domestic health accounts 2019/20. Available from: . Accessed 23 Dec 2022.

13. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice

Committee. 2. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes:

standards of care in diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care

2024;47(Suppl 1):S20-42. Crossref

14. Bajaj SS, Zhong A, Zhang AL, Stanford FC. Body mass

index thresholds for Asians: a race correction in need of

correction? Ann Intern Med 2024;177:1127-9. Crossref

15. Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government. Chronic

Disease Co-Care (CDCC) Pilot Scheme. Available from: https://www.primaryhealthcare.gov.hk/cdcc/en/. Accessed 25 Sep 2023.

16. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/

AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/

NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection,

Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in

Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American

College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task

Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol

2018;71:2199-269. Crossref

17. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH

Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension.

Eur Heart J 2018;39:3021-104. Crossref

18. Chan KK, Szeto CC, Lum CC, et al. Hong Kong College of

Physicians Position Statement and Recommendations on

the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart

Association and 2018 European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the

Management of Arterial Hypertension. Hong Kong Med J

2020;26:432-7. Crossref

19. Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government. The Primary

Healthcare Blueprint. Available from: https://www.primaryhealthcare.gov.hk/bp/en/index.html. Accessed 25 Sep 2023.

20. Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY.

Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death,

cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med

2004;351:1296-305. Crossref

21. Chan JY, Cheng YL, Yuen SK, et al. The Hong Kong Renal

Registry: a recent update. Hong Kong Med J 2024;30:332-6. Crossref

22. Tang SC, Wong AK, Mak SK. Clinical practice guidelines

for the provision of renal service in Hong Kong: general

nephrology. Nephrology (Carlton) 2019;24 Suppl 1:9-26. Crossref

23. Kar D, El-Wazir A, Delanerolle G, et al. Predictors and

determinants of albuminuria in people with prediabetes

and diabetes based on smoking status: A cross-sectional

study using the UK Biobank data. EClinicalMedicine

2022;51:101544. Crossref

24. Liu X, Shen P, Zhang D, et al. Evaluation of atherosclerotic

cardiovascular risk prediction models in China: results

from the CHERRY study. JACC Asia 2022;2:33-43. Crossref

25. Rodriguez F, Chung S, Blum MR, Coulet A, Basu S,

Palaniappan LP. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

risk prediction in disaggregated Asian and Hispanic

subgroups using electronic health records. J Am Heart

Assoc 2019;8:e011874. Crossref

26. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/

AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/

NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood

cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice

guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:e285-350. Crossref

27. Ndumele CE, Neeland IJ, Tuttle KR, et al. A synopsis of

the evidence for the science and clinical management of

cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome: a

scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

Circulation 2023;148:1636-64. Crossref

28. American Heart Association. The American Heart

Association PREVENTTM Online Calculator. Available from: https://professional.heart.org/en/guidelines-and-statements/prevent-calculator. Accessed 11 Jan 2024.

29. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular

disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice

guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:e177-232. Crossref

30. Huelsmann M, Neuhold S, Resl M, et al. PONTIAC

(NT-proBNP selected prevention of cardiac events in a

population of diabetic patients without a history of cardiac

disease): a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Am

Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1365-72. Crossref

31. Ledwidge M, Gallagher J, Conlon C, et al. Natriuretic

peptide-based screening and collaborative care for

heart failure: the STOP-HF randomized trial. JAMA

2013;310:66-74. Crossref

32. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection,

Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in

Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical

Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:e127-248. Crossref

33. Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart

Failure: Executive Summary: A Report of the American

College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint

Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:1757-80. Crossref

34. Ng IH, Cheung KK, Yau TT, Chow E, Ozaki R, Chan JC.

Evolution of diabetes care in Hong Kong: from the Hong

Kong Diabetes Register to JADE-PEARL Program to

RAMP and PEP Program. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul)

2018;33:17-32. Crossref

35. Yu EY, Wan EY, Mak IL, et al. Assessment of Hypertension

Complications and Health Service use 5 years after

implementation of a multicomponent intervention. JAMA

Netw Open 2023;6:e2315064. Crossref

36. Primary Healthcare Commission, Health Bureau, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Diabetes Care. Available from:

https://www.healthbureau.gov.hk/pho/rfs/english/reference_framework/diabetes_care.html. Accessed 3 Apr

2024.

37. Primary Healthcare Commission, Health Bureau, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Hypertension Care. Available

from: https://www.healthbureau.gov.hk/phcc/rfs/english/reference_framework/hypertension_care.html. Accessed 3 Apr 2024.

38. Kula AJ, Prince DK, Katz R, Bansal N. Mortality burden

and life-years lost across the age spectrum for adults living

with CKD. Kidney360 2023;4:615-21. Crossref

39. Eisenberg D, Shikora SA, Aarts E, et al. 2022 American

Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and

International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and

Metabolic Disorders (IFSO): indications for metabolic and

bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2022;18:1345-56. Crossref

40. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index

for Asian populations and its implications for policy and

intervention strategies. Lancet 2004;363:157-63. Crossref

41. Lui DT, Ako J, Dalal J, et al. Obesity in the Asia-Pacific

region: current perspectives. J Asian Pac Soc Cardiol

2024;3:e21. Crossref

42. Khunti K, Zaccardi F, Amod A, et al. Glycaemic control is

still central in the hierarchy of priorities in type 2 diabetes

management. Diabetologia 2025;68:17-28. Crossref

43. Naito R, Miyauchi K, Daida H. Racial differences in the

cholesterol-lowering effect of statin. J Atheroscler Thromb

2017;24:19-25. Crossref

44. Tomlinson B, Chan P, Liu ZM. Statin responses in Chinese

patients. J Atheroscler Thromb 2018;25:199-202. Crossref

45. Sun H, Lai A, Tan GM, Yan B. Therapeutic gaps in low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol management have narrowed

over time but remain wide: a wide study of 40,141 acute

coronary syndrome patients from 2016 to 2021. Eur Heart

J 2023;44 (Suppl 2):ehad655-2800. Crossref

46. Writing Committee Members; Joglar JA, Chung MK,

et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the

Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A

Report of the American College of Cardiology/American

Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice

Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024;83:109-279. Crossref

47. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes CKD Work

Group. KDIGO 2024 clinical practice guideline for the

evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease.

Kidney Int 2024;105:S117-314. Crossref