Hong Kong Med J 2025;31:Epub 14 Apr 2025

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Willingness to pay and preferences for mindfulness-based interventions among patients with chronic low back pain in the Hong Kong public healthcare sector

Mengting Zhu, PhD1; Phoenix KH Mo, PhD1; Kailu Wang, PhD1; Hermione HM Lo, MSc1; YK Choi, PGDip2; SW Law, MSc3; Regina WS Sit1, MD

1 The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Family Medicine, The New Territories East Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof Regina WS Sit (reginasit@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Low back pain (LBP) is a leading

cause of disability worldwide. Mindfulness-based

interventions (MBIs) are effective for LBP

management when combined with medication and

physical therapy. An understanding of patients’

willingness to pay (WTP) and preferences is needed

to integrate MBIs into standard LBP care. We

examined WTP and preferences for MBIs, as well as

associated factors, among patients with chronic LBP

in the Hong Kong public healthcare sector.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted

in two Hong Kong public hospitals. We used the

payment card method to assess patients’ WTP for

MBIs and performed a discrete choice experiment

to examine patients’ preferences for MBIs. Tobit

regression was utilised to analyse factors associated

with WTP for MBIs. Patients’ relative preferences for

MBIs were estimated through a mixed logit model.

Results: Mean WTP for an eight-session course of

MBIs was HK$258.75±508.11. Higher pain scores,

monthly family income >HK$30 000, high school

education, higher treatment expenses, and stronger

belief in MBIs were associated with greater WTP.

Patients were more likely to choose MBIs with lower

costs, greater improvements in pain relief and the

ability to perform daily activities, and a face-to-face

delivery mode.

Conclusion: Patients with chronic LBP exhibited

low WTP for MBIs. Strategies to improve education

and awareness may enhance WTP; affordability and

accessibility should be considered for individuals

from diverse socio-economic backgrounds. The

identified preferences provide insights for designing

MBIs that align with patient needs. These findings

offer valuable methodological references for other

healthcare evaluations.

New knowledge added by this study

- Patients with chronic low back pain have a low willingness to pay for mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs).

- Individuals experiencing more severe pain and possessing greater financial capacity are more willing to pay for MBIs.

- Patients prefer MBIs with lower costs, greater treatment effectiveness, and a face-to-face delivery mode.

- These findings have practical implications for the future implementation of MBIs in chronic pain management.

- This study provides a methodological reference that could be adapted for evaluation of similar treatments in diverse international settings.

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is a prevalent health condition

that can have disabling effects on individuals of

all ages.1 This condition also imposes substantial

socio-economic costs, as evidenced by studies

demonstrating its impacts on healthcare systems

and workforce productivity worldwide.2 3

Psychological treatments, particularly when

combined with medication and physical therapy,

are effective in managing LBP.4 Mindfulness-based

interventions (MBIs; ie, evidence-based

psychological approaches) have been shown to

reduce pain, disability, and psychological distress

associated with LBP.5 Moreover, studies have emphasised the cost-effectiveness of MBIs in

reducing chronic pain–related healthcare expenses

and productivity losses.6 7 Although the exact

mechanisms through which MBIs alleviate pain have

not been elucidated, there is evidence that they may

alter pain signal processing in the brain, fostering

acceptance and non-judgemental awareness. These

outcomes enhance pain tolerance and reduce

emotional reactivity to pain.8

Other commonly used social and

psychotherapeutic modalities include cognitive-behavioural

therapy and acceptance and commitment

therapy. Cognitive-behavioural therapy targets

maladaptive thought patterns and behaviours,9

whereas acceptance and commitment therapy

focuses on promoting psychological flexibility

despite the presence of pain.10 Mindfulness-based

interventions uniquely emphasise cultivating

present-moment awareness and acceptance of pain

sensations.11 Key advantages of MBIs include their

accessibility and cost-effectiveness: they can be

efficiently delivered in group settings (either online

or face-to-face), facilitating scalability for public

healthcare initiatives.12 13 Moreover, they have the

potential to enhance self-management skills for

sustainable pain management.14 Acceptance and

commitment therapy has limited empirical support

and mixed results regarding its effectiveness in terms of improving pain intensity among patients

with chronic pain.15 16 Cognitive-behavioural therapy

is a widely used and well-researched therapeutic

approach for chronic pain.12 However, it is considered

suitable for one-on-one (rather than group-based)

formats because it requires personalised

treatment plans that address the unique needs and

concerns of each patient.17 Furthermore, MBIs have

demonstrated greater cost-effectiveness relative to

cognitive-behavioural therapy among patients with

chronic LBP.18

In Hong Kong, approximately 90% of specialist

and inpatient care services and 30% of primary

care services are provided by the public sector.19

Given the absence of universal health insurance or

co-payment, the majority of chronic diseases (eg,

LBP) are managed within the public healthcare

system.20 The incorporation of MBIs into standard

LBP treatment within this system requires an

understanding of patients’ willingness to pay (WTP)

and preferences. Relatively few studies have explored

WTP or preferences for MBIs among patients with

chronic LBP. An understanding of WTP is crucial

for efforts to assess the perceived value of healthcare

interventions, inform policy decisions, and guide

resource allocation.21 22 Consideration of patient

preferences in healthcare service decisions can

improve uptake, adherence, efficiency, and patient

satisfaction while reducing costs.23 24

This study aimed to estimate WTP and

preferences for MBIs among patients with chronic

LBP in the public healthcare sector and to explore

factors associated with WTP and preferences for

MBIs.

Chronic LBP is significantly influenced by

psychological factors; social determinants play a

crucial role in the interpretation of chronic LBP

and the ways that individuals seek and receive pain

treatment.25 26 The socio-psychobiological model

of chronic pain represents a paradigmatic shift

from the conventional biopsychosocial model.27 28

Whereas the latter model recognises the interplay

of social, psychological, and biological factors, it

tends to prioritise biological determinants over

social and psychological aspects.27 28 In contrast, the

socio-psychobiological model primarily emphasises

social determinants, followed by psychological and

biological factors.27 28

Our research, which assesses WTP and

preferences for MBIs in the context of chronic

LBP, aligns with the socio-psychobiological model

for pain management. The examination of WTP

and preferences can provide valuable insights into

the socio-economic backgrounds of individuals

with chronic LBP, which may strongly influence

their experiences of pain and responses to pain

management interventions. The findings may

also clarify patients’ abilities to access and afford pain management strategies.29 This aspect is

particularly important because it underscores the

social dimensions of chronic pain management,

highlighting disparities and barriers that may exist in

pain experiences and access to effective interventions.

Furthermore, MBIs constitute a psychological and

group-based approach to chronic pain management,

addressing both psychological and social factors

emphasised within the socio-psychobiological

model.12 30 These interventions provide individuals

with skills to manage psychological distress linked

to chronic LBP while also promoting social support

and connectivity in group settings.31 32 By fostering

mindfulness practices, MBIs equip individuals with

coping mechanisms to navigate the psychological

distress often associated with chronic LBP, while also

enhancing social support and connectivity within

group settings.31 32

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a prospective cross-sectional

survey using convenience sampling to recruit

eligible patients with chronic LBP from two Hong

Kong public hospitals between September 2022

and February 2023. We utilised a discrete choice

experiment (DCE) design to examine preferences

for MBIs. This study adhered to the STROBE

(Strengthening the Reporting of Observational

Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines.

Participants

The inclusion criteria for this study were age ≥18

years, chronic non-specific LBP, and the ability

to speak and understand Chinese. Chronic non-specific

LBP was defined as pain in the lumbosacral

region, with or without sciatica, that persisted for

>3 months and lacked a clearly identifiable cause

or pathology based on clinical evaluation, imaging,

or laboratory tests. Exclusion criteria were chronic

LBP with a specific identifiable cause or pathology,

such as inflammatory diseases, tumours, infections,

fractures, structural abnormalities, or other spinal

pathologies evident on clinical evaluation, imaging,

or laboratory tests. Patients who did not provide

written informed consent, were pregnant, or were

<6 months postpartum or post-weaning were also

excluded.

Sample size calculation

To determine the sample size for evaluating WTP,

we used the payment card elicitation format sample

size formula established by Mitchell and Carson.33

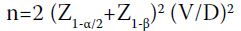

The formula is:

where n is the minimum required sample size, Z1-α/2

represents the desired confidence interval, Z1-β corresponds to the value for power, V denotes the

coefficient of variation (ie, ratio of estimated standard

deviation of WTP to estimated mean WTP), and D is

the designed effect (ie, percentage difference between

true WTP and mean of estimated WTP bids). For

this study, assuming α=0.05, β=0.20, V=0.98 (based

on a previous study evaluating WTP for reduced

pain intensity among patients with chronic pain),34

and D=0.20, the calculated minimum sample size

was 470, considering a 20% non-response rate.

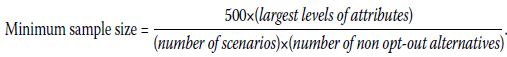

To explore preferences for MBI receipt using a

DCE design, we applied the rule of thumb described

by Orme35 and Johnson and Orme.36 The minimum

sample size required for the main effects was

calculated as follows:

Under conditions of two alternatives, a maximum of

four attribute levels and eight scenarios per patient, a

minimum of 125 patients was required. Considering

two subgroups with different characteristics and

a 20% non-response rate, the adjusted minimum

sample size was 312.

Survey data

A self-administered questionnaire was used to

collect data. An onsite research assistant invited

patients in the clinic waiting area to participate in

the survey and was available to provide assistance if

needed.

Independent variable

The independent variables of the study are as follows:

- Socio-demographic characteristics: Age, gender, education level, employment status, and personal and family income were recorded.

- General self-reported health status: A single-item self-rated health scale was used to assess participants’ self-rated health, with response options ranging from ‘Very good’ to ‘Very poor.’37 Studies have shown that this scale is associated with patients’ WTP for pain treatments.38 39 40 41

- Knowledge and usage of MBIs: Knowledge of mindfulness was assessed using two items adapted from a previous study that investigated health professionals’ and health profession students’ knowledge of and attitudes toward mindfulness.42 The items were as follows: (1) What is the extent of your knowledge of MBIs? (2) Might MBIs be useful for treating chronic pain? Usage of MBIs was determined using two items adapted from a previous study that evaluated employees’ preferences for accessing MBIs.43 The items were as follows: (1) Have you ever participated in mindfulness courses? (2) How many mindfulness sessions have you attended?

- Pain-related characteristics: Pain-related characteristics included pain duration, pain intensity, disability, and frequency of treatment for chronic LBP. Pain intensity was measured using an 11-point Numeric Rating Scale (NRS).44 Disability was assessed using the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire.45 Pain duration was determined by asking participants to report the number of months they had experienced an ongoing LBP problem. Frequency of treatment was evaluated by asking participants to report how many times they had consulted a doctor or other healthcare professional for LBP in the past 12 months.

- Satisfaction with current treatment: An item was adapted from a previous study that assessed treatment satisfaction in patients with osteoarthritis and LBP.46 This item asked participants to rate their satisfaction with the effectiveness of current treatment in controlling LBP.

- Monthly expenses on current treatment: Participants were asked to report their monthly expenses with respect to chronic LBP treatment.

Dependent variables

Willingness to pay and preferences for MBIs were

the two dependent variables of the current study.

The payment card method was used to assess WTP

for MBIs.47 This approach minimises starting point

bias and reduces the high rate of item non-response

relative to other elicitation methods.48 To ensure that

participants were familiar with MBIs, we provided

an introduction using a text description and a video

before each participant responded to the WTP

question (online supplementary Fig). Participants

were presented with a range of monetary values

(HK$0 to HK$10 000) and asked to select the value

that best represented the amount they would be

willing to pay for MBIs. Additionally, WTP for

pain reduction was evaluated using two items

adapted from a previous study that assessed WTP

for reductions in chronic LBP and neck pain using

the payment card method.49 These items asked

participants to indicate the amount they would be

willing and able to pay out-of-pocket per month for

their chronic LBP to be reduced by half or entirely

eliminated. Participants unwilling to pay any amount

were asked to specify their reasons.

Participants were invited to respond to

eight choice sets evaluating patient preferences

for MBIs. In each choice task, they were asked

to select their most preferred option from two

hypothetical MBIs with different attribute levels. To

ensure comprehension, we included a test scenario

with a dominant alternative. If participants did

not choose the dominant option, research staff

provided clarification. Internal validity was assessed

by including a choice set with dominant pairs, in which one alternative was clearly superior across

all attributes.

Statistical analyses

Complete-case analysis was utilised for the

dependent variable of WTP for MBIs. The Tobit

regression model was used to estimate the

associated factors.50 This model was selected

because WTP measures exhibited left-censoring

(ie, a substantial proportion of zero values [46.6%

of the sample]; the remaining responses indicated

positive WTP for MBIs). Multicollinearity was

examined using tolerance and the variance inflation

factor (VIF). Continuous variables were presented

as mean±standard deviation. The level of statistical

significance was set at 5%.51

Study design

A DCE design was used in this study to examine

the preferences of individuals with chronic LBP

for MBIs. The DCE comprised four key steps: (1)

conducting a literature review to identify conceptual

attributes and levels; (2) conducting qualitative

research to determine contextual attributes and

levels; (3) integrating attributes and levels into

choice sets, conducting pilot tests, and refining the

questionnaire; and (4) collecting experimental data

and performing data analysis.

Systematic review

A systematic review of DCEs examining patient

preferences for non-surgical treatments in chronic

musculoskeletal pain was conducted.52 Studies that

used DCEs to evaluate patient preferences for the

management of chronic musculoskeletal pain were

included.

Qualitative research

Participants with chronic LBP were invited to discuss

characteristics of MBIs they might consider valuable

when deciding whether to participate in MBIs. These

valued characteristics were summarised. A panel

of experts from relevant fields (chronic pain, DCE

methodology, and psychology) then reviewed and

refined the attributes and levels, selecting six to eight

attributes for inclusion.

Generation of choice sets, piloting, and refinement

of the questionnaire

A D-efficient experimental design was used to

generate choice sets, which were randomly assigned

to five blocks. A pilot DCE survey was conducted to

assess cognitive difficulty and questionnaire length.

Twenty patients with chronic LBP participated in the

pilot study; they provided feedback and suggestions

for improvement.

Experimental data collection and data analysis

Discrete choice experiment data were collected as

part of the cross-sectional survey. Respondents’

relative preferences were estimated using a mixed

logit model with panel specification to adjust

for correlated choices within individuals. The

coefficients of four variables—‘improvement in

capacity to perform daily life activities’, ‘risk of

adverse events’, ‘improvement in pain relief’, and

‘out-of-pocket costs’—were assumed to be random,

following a zero-bounded triangular distribution

because the distribution of these random

parameters should comprise only positive or

negative values. ‘Out-of-pocket costs’ was specified

as a continuous variable in the mixed logit model.

The marginal WTP for different levels within each

attribute was calculated through division of the

negative estimated beta coefficient for each level

by the estimated beta coefficient for ‘out-of-pocket

costs’. The log-likelihood and adjusted McFadden’s

pseudo–R-squared were calculated to assess model

goodness of fit. Higher log-likelihood and adjusted

McFadden’s pseudo–R-squared values indicate a

better-fitting model.53 54 Subgroup analyses were

conducted to assess preference heterogeneity

across characteristics, including age, gender, family

monthly income, and education.

Results

Participant characteristics

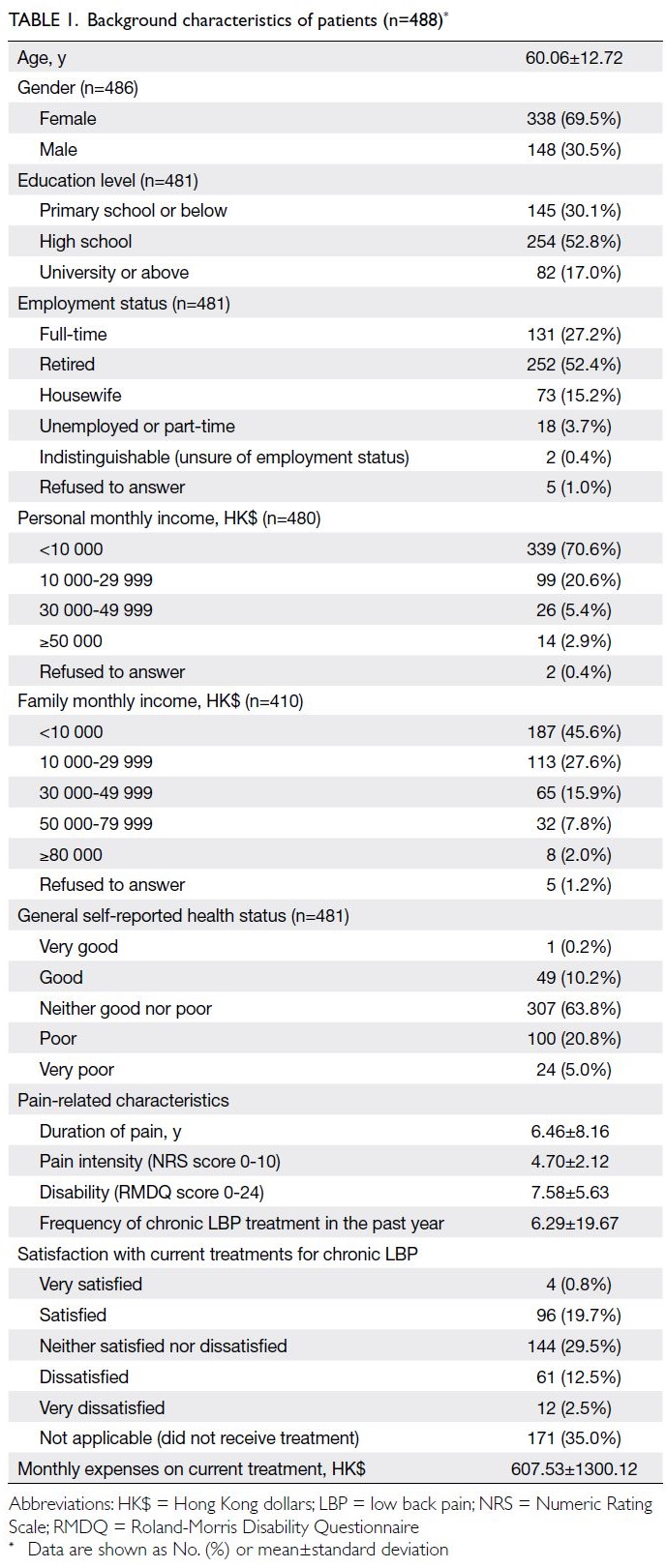

Of the 589 participants invited, 488 questionnaires

were returned, yielding a response rate of 82.9%. The

study sample had a mean age of 60.06±12.72 years;

69.5% of the participants were women. The average

pain duration was 6.46±8.16 years; mean NRS and

Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire scores were

4.70±2.12 and 7.58±5.63, respectively. Participant

characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

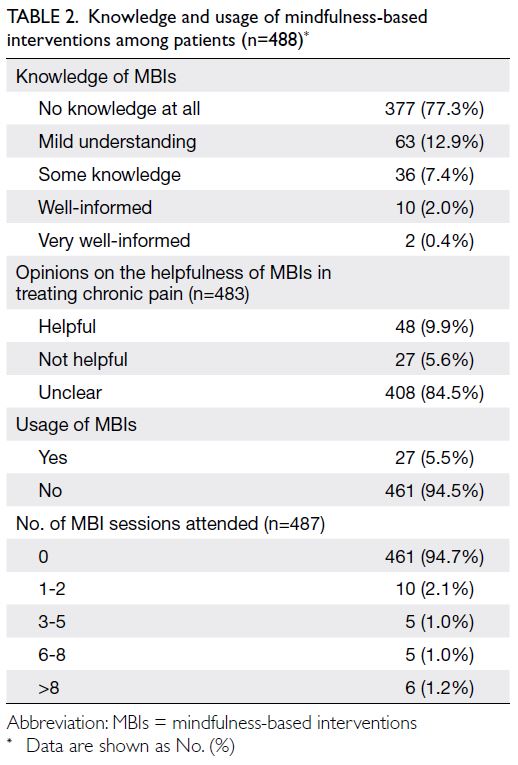

Knowledge and usage of mindfulness-based

interventions

Regarding knowledge and usage of MBIs, 77.3%

of participants were unfamiliar with MBIs, 84.5%

were uncertain about their effectiveness in treating

chronic LBP, and 94.5% had never attended an

MBI session. Knowledge and usage of MBIs are

summarised in Table 2.

Willingness to pay for pain reduction and

mindfulness-based interventions

The mean monthly WTP values for MBIs to reduce

pain by half and to entirely eliminate pain were

HK$684.68±1347.43 and HK$1102.70±1983.83,

respectively. The overall mean WTP for an eightsession

MBI programme was HK$258.75±508.11.

Among the participants, 237 were not willing to pay for MBIs, citing reasons such as limited

knowledge of MBIs, unwillingness to spend money

on treatment, lack of time, and scepticism regarding

MBI effectiveness (online supplementary Table 1).

Results of multicollinearity tests

Multicollinearity among the independent variables

was assessed; all tolerance values were >0.25 and VIF

values were <4, except for two similar variables (ie,

usage of MBIs measured as a binary variable [‘Yes’

or ‘No’] and number of MBI sessions attended).

Given that only a small number of participants had

attended MBIs, the variable measuring the number

of MBI sessions was selected for inclusion in the

Tobit regression model (online supplementary Table 2).

Factors associated with willingness to pay for

mindfulness-based interventions

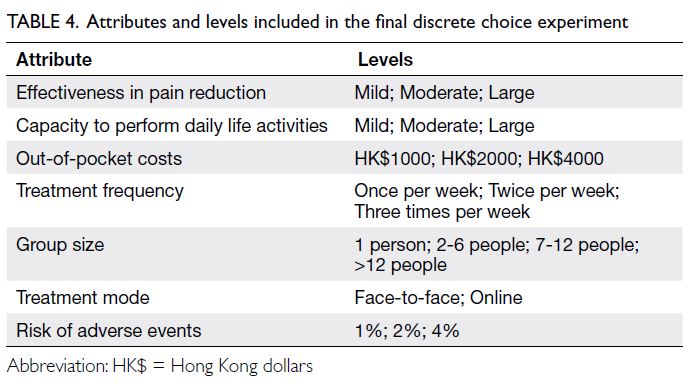

Factors associated with WTP for MBIs are

summarised in Table 3. Participants with a higher

NRS score (β=81.26; P=0.003), family monthly

income of ≥HK$30 000 (β=320.1; P=0.035), high

school education (β=242.94; P=0.045), and higher

monthly expenses on chronic LBP treatment

(β=0.11; P=0.003) were more willing to pay for MBIs.

Conversely, participants who did not believe in the

usefulness of MBIs (β=-528.88; P=0.033) were less

willing to pay for them.

Table 3. Factors associated with willingness to pay for mindfulness-based interventions according to Tobit regression (n=488)

Evaluation of patient preferences for

mindfulness-based interventions

Conceptual attributes and levels identified

through literature review

In total, 15 eligible studies were included.52 The

attributes most frequently cited were ‘capacity to

realize daily life activities’, ‘risk of adverse events’,

‘effectiveness in pain reduction’, and ‘out-of-pocket

costs’, which were also ranked among the top three

most important attributes. Other attributes, cited

less frequently but revealing important preferences,

included ‘treatment frequency’ and ‘onset of

treatment efficacy’.52

Contextual attributes and levels identified

through qualitative research

Eight patients with chronic LBP participated in this

stage of developing contextual attributes through

patient-public involvement. Two focus group

interviews were conducted to identify contextual

attributes. Valued characteristics of MBIs were

summarised, including effectiveness in pain

reduction, mood regulation, and sleep improvement;

treatment environment; reliability of mindfulness

instructors; reputation of the organisation; safety;

affordability; flexibility (availability of online

resources at all times); availability of follow-up courses; and a group-based course format. Three

experts finalised the selection of seven attributes for

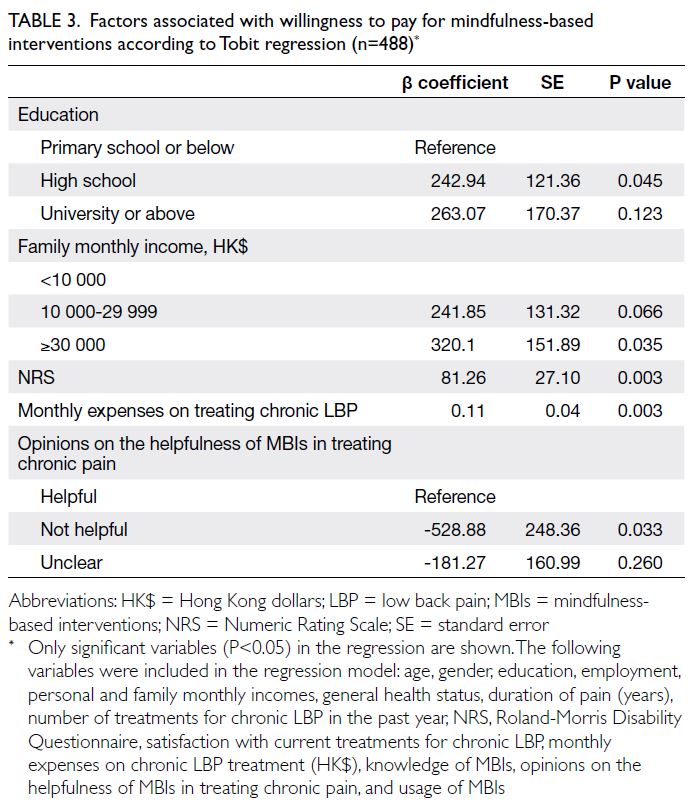

inclusion (Table 4).

Pilot study of discrete choice experiment

Only minor changes in terminology were applied to

attribute levels after the pilot study. This pilot study

verified the attributes and their levels, as presented

in Table 4. The pilot study also indicated that most patients understood the instructions and attributes.

Only minor layout adjustments were made—some

participants reported that the font size was too small.

Factors associated with patients’ preferences for

mindfulness-based interventions

After the exclusion of participants who declined

to answer DCE questions due to difficulties in

comprehension or unwillingness to respond (n=69,

14.1%) and those with missing DCE responses (n=4,

0.8%), the final participant count was reduced to 415.

Among these participants, six (1.4%) did not pass the dominance test; thus, 409 participants were included

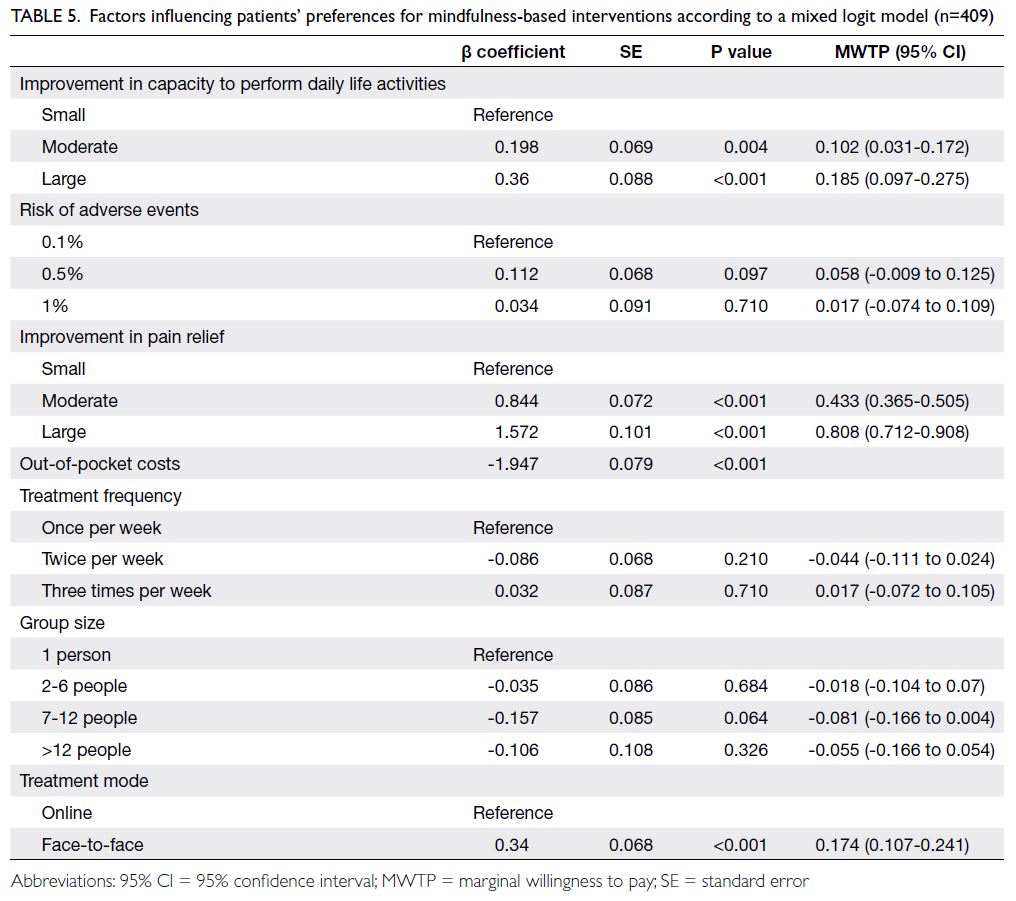

in the analysis. The results of the DCE examining

factors associated with patients’ preferences for

MBIs are presented in Table 5. Participants were

more likely to choose MBIs with lower out-of-pocket

costs, higher levels of pain relief, and greater improvements in capacity to perform daily

life activities. Face-to-face treatment modes were

preferred over online formats. Regarding model fit,

the log-likelihood and adjusted McFadden’s pseudo–R-squared for the mixed logit model were -1502.8

and 0.330, respectively.

Table 5. Factors influencing patients’ preferences for mindfulness-based interventions according to a mixed logit model (n=409)

Subgroup analyses

The results of subgroup analyses are presented in

online supplementary Tables 3 to 6. Preferences

differed substantially between age-groups, family

income levels, and education levels, but showed no

gender-based significant differences. Improvement

in the capacity to perform daily life activities

was an important attribute when selecting MBIs

for older participants, those with lower family

monthly income, and those with higher education

level; this attribute was not important for younger

participants and those with higher family monthly

income and lower education level. Group size was

an important attribute for younger participants and

those with higher family monthly income but not

for older participants or those with lower family

monthly income. Younger participants and those

with higher family monthly income preferred MBIs

with a group size of one person, rather than 7 to 12

people. Treatment mode was an important attribute

for participants with lower family monthly income

and higher education level but not for those with

higher family monthly income and lower education.

Participants with lower family monthly income and

higher education preferred face-to-face treatment

over online treatment. Furthermore, participants

with lower family monthly income and older age

placed greater priority on out-of-pocket costs for

MBIs, as indicated by substantially larger regression

coefficients for out-of-pocket costs in subgroup

analyses.

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies,34 49 we found

that patients with higher pain scores, higher

family income, and higher monthly expenses on

LBP treatment were more willing to pay for MBIs.

Comparison of WTP for MBIs in this study to

a national survey on WTP for complementary

and alternative medicine treatments in England55

revealed that participants in the present study had

a lower WTP. One possible explanation for this

discrepancy is that complementary and alternative

medicine practices, such as acupuncture and herbal

medicine, are more established in some cultures;

MBIs are relatively new and may be less familiar to

our study population.

In Hong Kong’s public healthcare system,

physiotherapy and occupational therapy for chronic

pain cost HK$80 per visit. If MBIs followed this fee structure, eight sessions would cost a total of

HK$640. However, the current WTP for MBIs is

HK$258.75, approximately 40% of this cost. Notably,

WTP was calculated in a population with limited

knowledge of MBIs. Increased awareness of their

efficacy may enhance WTP, aligning it more closely

with the existing fee structure.

Our study evaluating preferences for MBIs

confirmed previous findings that chronic pain

treatment preferences are significantly influenced by

treatment effectiveness and out-of-pocket costs.52 56 57

However, in contrast to prior studies,52 56 57 we found

that the risk of adverse events was not an attribute

considered important by patients with chronic LBP

during MBI selection. One possible explanation is

that the risk of adverse events from psychological

interventions is lower and less severe than the risk

of such events associated with pharmacological

or exercise-based interventions.58 59 60 Additionally,

we observed that treatment mode constituted

an important attribute of MBIs, consistent with

investigations of exercise therapy preferences among

patients with chronic pain.39

Our study focused on assessing WTP and

preferences for MBIs in chronic LBP, following the

socio-psychobiological model that prioritises social

and psychological factors over biological factors.27 28

This approach provides insights into the socio-economic

backgrounds of patients with chronic

LBP and highlights their pain experiences and

access to pain management strategies, emphasising

the social dimension of chronic pain management.

Mindfulness-based interventions, as a psychological

and group-based approach, equip individuals with

skills to manage psychological distress related to

chronic LBP while fostering social support and

connectivity through group interaction.

The current approach to chronic pain care

often results in the underutilisation of high-value

care (eg, psychological therapies) and overuse of low-value

care, including invasive procedures and opioid

medications.4 28 The adoption and implementation

of a socio-psychobiological model could serve as an

effective strategy for establishing pain care systems

that prioritise high-value care.27 28

Despite the recognised value of MBIs in

chronic pain management, their limited integration

into clinical practice may be attributed to patients’

unfamiliarity and lack of knowledge about these

interventions, coupled with insufficient investment

in primary care resources. Additionally, economic

incentives often favour high-volume practice models

in primary care settings.28 Thus, there is an urgent

need for educational initiatives to enhance awareness

and knowledge of MBIs among individuals with

chronic LBP, as well as increased investment in

primary care resources.

This study provided critical insights into the integration of MBIs for chronic LBP management

within the Hong Kong public healthcare system. In

the context of Hong Kong’s public healthcare settings,

we propose integrating MBIs as an intermediary

step between primary care and specialist care for

chronic LBP management. Primary care providers

could identify patients experiencing psychological

and social distress who may benefit from MBIs and

facilitate their referral for MBI treatment. Patients

whose condition does not improve after an MBI

could then be referred to specialist clinics. This

approach could substantially reduce waiting times

for chronic LBP treatment within the Hong Kong

public healthcare system.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. To our knowledge,

it is the first investigation to assess WTP and

preferences for MBIs in chronic pain management;

it included a comprehensive list of independent

variables covering key factors that influence WTP.

Additionally, the study utilised a mixed logit

model to consider preference heterogeneity within

the sample. Furthermore, a rigorous systematic

review and qualitative interviews informed the

attributes and levels used in the DCE. However,

certain limitations should be acknowledged. First,

participants’ limited knowledge of MBIs may

have influenced WTP and preferences. Second,

participants were recruited through convenience

sampling from outpatient clinics in two Hong

Kong public hospitals, which may have introduced

selection bias that skewed the sample composition

and limited its representativeness. This limitation

may affect the generalisability of the findings beyond

the specific group sampled. Third, the cross-sectional

design of the study precluded establishment of

causal relationships between WTP and preferences

for MBIs, as well as associated factors.

Although WTP and preferences are essential

considerations for MBI implementation, they

should not be the sole determinants. Factors such

as cost-effectiveness, impact on quality of life, and

infrastructure availability must also be considered.

Further research is required to provide additional

evidence for implementation within the Hong

Kong public healthcare system. Nevertheless, this

study established a rationale for assessing WTP

and preferences for MBIs, with a methodology that

can be adapted for healthcare evaluations in other

countries.

Conclusion

This study highlights the need to increase awareness

of MBIs for chronic LBP management within the

public healthcare system. The findings indicate

low WTP among participants, suggesting a gap in understanding and utilisation. Notably, individuals

with higher pain scores, higher family income, and

higher monthly LBP treatment expenses, as well as

a stronger belief in MBIs, were more willing to pay

for such interventions; these observations indicate

targeted demand. Patient preferences favoured

lower costs, face-to-face treatment, and enhanced

effectiveness. These findings provide practical

insights for designing patient preference–aligned

MBIs and will serve as valuable references for future

healthcare evaluations.

Author contributions

Concept or design: M Zhu, PKH Mo, RWS Sit.

Acquisition of data: M Zhu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: M Zhu.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: M Zhu.

Analysis or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: M Zhu.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, RWS Sit was not involved in the

peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts

of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Joint Chinese University of

Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research

Ethics Committee, Hong Kong (Ref. No.: 2022.279). The

research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of

Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent

before completing the questionnaire.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during

the current study are not publicly available due to ethics

restrictions. A request for the code can be made directly to

the corresponding author.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and

some information may not have been peer reviewed. Accepted

supplementary material will be published as submitted by the

authors, without any editing or formatting. Any opinions

or recommendations discussed are solely those of the

author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association.

The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong

Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility

arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, et al. The global burden of low

back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease

2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:968-74. Crossref

2. Dieleman JL, Cao J, Chapin A, et al. US health care

spending by payer and health condition, 1996-2016. JAMA

2020;323:863-84. Crossref

3. Hong J, Reed C, Novick D, Happich M. Costs associated

with treatment of chronic low back pain: an analysis of the

UK General Practice Research Database. Spine (Phila Pa

1976) 2013;38:75-82. Crossref

4. Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al. Prevention and

treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and

promising directions. Lancet 2018;391:2368-83. Crossref

5. Anheyer D, Haller H, Barth J, Lauche R, Dobos G, Cramer H.

Mindfulness-based stress reduction for treating low back

pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern

Med 2017;166:799-807. Crossref

6. Herman PM, Anderson ML, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH,

Turner JA, Cherkin DC. Cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based

stress reduction versus cognitive behavioral therapy

or usual care among adults with chronic low back pain.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017;42:1511-20. Crossref

7. Pérez-Aranda A, D’Amico F, Feliu-Soler A, et al. Cost-utility

of mindfulness-based stress reduction for fibromyalgia

versus a multicomponent intervention and usual care:

a 12-month randomized controlled trial (EUDAIMON

study). J Clin Med 2019;8:1068. Crossref

8. Day MA, Jensen MP, Ehde DM, Thorn BE. Toward

a theoretical model for mindfulness-based pain

management. J Pain 2014;15:691-703. Crossref

9. Ehde DM, Dillworth TM, Turner JA. Cognitive-behavioral

therapy for individuals with chronic pain: efficacy,

innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol

2014;69:153-66. Crossref

10. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J.

Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes

and outcomes. Behav Res Ther 2006;44:1-25. Crossref

11. Zhang D, Lee EK, Mak EC, Ho CY, Wong SY. Mindfulness-based

interventions: an overall review. Br Med Bull

2021;138:41-57. Crossref

12. Khoo EL, Small R, Cheng W, et al. Comparative evaluation

of group-based mindfulness-based stress reduction

and cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment

and management of chronic pain: a systematic review

and network meta-analysis. Evid Based Ment Health

2019;22:26-35. Crossref

13. Liu Z, Jia Y, Li M, et al. Effectiveness of online mindfulness-based

interventions for improving mental health in

patients with physical health conditions: systematic review

and meta-analysis. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2022;37:52-60. Crossref

14. Khusid MA, Vythilingam M. The emerging role of

mindfulness meditation as effective self-management

strategy, part 2: clinical implications for chronic pain,

substance misuse, and insomnia. Mil Med 2016;181:969-75. Crossref

15. Veehof MM, Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Schreurs KM.

Acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for the

treatment of chronic pain: a meta-analytic review. Cogn

Behav Ther 2016;45:5-31. Crossref

16. Hughes LS, Clark J, Colclough JA, Dale E, McMillan D.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for chronic

pain: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin J Pain 2017;33:552-68. Crossref

17. Gryesten JR, Poulsen S, Moltu C, Biering EB, Møller K,

Arnfred SM. Patients’ and therapists’ experiences of

standardized group cognitive behavioral therapy: needs

for a personalized approach. Adm Policy Ment Health

2024;51:617-33. Crossref

18. Zhang L, Lopes S, Lavelle T, et al. Economic evaluations

of mindfulness-based interventions: a systematic review.

Mindfulness (N Y) 2022;13:2359-78. Crossref

19. Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Thematic Household Survey Report No.

50. Jan 2013. Available from: https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B11302502013XXXXB0100.pdf. Accessed 7 Apr 2025.

20. Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government. The

healthcare challenges in Hong Kong. 2022. Available

from: https://www.primaryhealthcare.gov.hk/bp/en/supplementary-documents/challenges/. Accessed 18 Mar 2025.

21. Abbas SM, Usmani A, Imran M. Willingness to pay and its

role in health economics. JBUMDC 2019;9:62-6.

22. Liu S, Yam CH, Huang OH, Griffiths SM. Willingness to

pay for private primary care services in Hong Kong: are

elderly ready to move from the public sector? Health Policy

Plan 2013;28:717-29. Crossref

23. Krist AH, Tong ST, Aycock RA, Longo DR. Engaging

patients in decision-making and behavior change to

promote prevention. Stud Health Technol Inform

2017;240:284-302. Crossref

24. Ostermann J, Brown DS, de Bekker-Grob EW,

Mühlbacher AC, Reed SD. Preferences for health

interventions: improving uptake, adherence, and efficiency.

Patient 2017;10:511-4. Crossref

25. Alhowimel A, AlOtaibi M, Radford K, Coulson N.

Psychosocial factors associated with change in pain and

disability outcomes in chronic low back pain patients

treated by physiotherapist: a systematic review. SAGE

Open Med 2018;6:2050312118757387. Crossref

26. Karran EL, Grant AR, Moseley GL. Low back pain and

the social determinants of health: a systematic review and

narrative synthesis. Pain 2020;161:2476-93. Crossref

27. Carr DB, Bradshaw YS. Time to flip the pain curriculum?

Anesthesiology 2014;120:12-4. Crossref

28. Mardian AS, Hanson ER, Villarroel L, et al. Flipping the

pain care model: a sociopsychobiological approach to

high-value chronic pain care. Pain Med 2020;21:1168-80. Crossref

29. Allen-Watts K, Sims AM, Buchanan TL, et al.

Sociodemographic differences in pain medication

usage and healthcare provider utilization among adults

with chronic low back pain. Front Pain Res (Lausanne)

2022;2:806310. Crossref

30. Majeed MH, Ali AA, Sudak DM. Mindfulness-based

interventions for chronic pain: evidence and applications.

Asian J Psychiatr 2018;32:79-83. Crossref

31. Smith SL, Langen WH. A systematic review of mindfulness

practices for improving outcomes in chronic low back pain.

Int J Yoga 2020;13:177-82. Crossref

32. Petrucci G, Papalia GF, Russo F, et al. Psychological

approaches for the integrative care of chronic low back

pain: a systematic review and metanalysis. Int J Environ

Res Public Health 2021;19:60. Crossref

33. Mitchell RC, Carson RT. Using Surveys to Value Public

Goods: The Contingent Valuation Method. New York and London: Resources for the Future; 1989.

34. Chuck A, Adamowicz W, Jacobs P, Ohinmaa A, Dick B,

Rashiq S. The willingness to pay for reducing pain and

pain-related disability. Value Health 2009;12:498-506. Crossref

35. Orme BK. Sample size issues for conjoint analysis studies.

In: Orme BK, editor. Getting Started with Conjoint

Analysis: Strategies for Product Design and Pricing

Research. 4th ed. Madison [WI]: Research Publishers LLC;

1998: 57-65.

36. Johnson R, Orme B. Sawtooth Software Research Paper

Series. Getting the most from CBC. WA: Sawtooth

Software; 2003. Available from: https://sawtoothsoftware.com/resources/technical-papers/getting-the-most-from-cbc. Accessed 24 Mar 2025.

37. Hanmer J. Measuring population health: association

of self-rated health and PROMIS measures with social

determinants of health in a cross-sectional survey of the

US population. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2021;19:221. Crossref

38. Copsey B, Buchanan J, Fitzpatrick R, Lamb SE, Dutton SJ,

Cook JA. Duration of treatment effect should be considered

in the design and interpretation of clinical trials: results

of a discrete choice experiment. Med Decis Making

2019;39:461-73. Crossref

39. Cranen K, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CG, Vollenbroek-Hutten MM, IJzerman MJ. Toward patient-centered

telerehabilitation design: understanding chronic

pain patients’ preferences for web-based exercise

telerehabilitation using a discrete choice experiment. J

Med Internet Res 2017;19:e26. Crossref

40. Ferreira GE, Howard K, Zadro JR, O’Keeffe M, Lin CC,

Maher CG. People considering exercise to prevent low

back pain recurrence prefer exercise programs that differ

from programs known to be effective: a discrete choice

experiment. J Physiother 2020;66:249-55. Crossref

41. Laba TL, Brien JA, Fransen M, Jan S. Patient preferences

for adherence to treatment for osteoarthritis: the

MEdication Decisions in Osteoarthritis Study (MEDOS).

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:160. Crossref

42. McKenzie SP, Hassed CS, Gear JL. Medical and psychology

students’ knowledge of and attitudes towards mindfulness

as a clinical intervention. Explore (NY) 2012;8:360-7. Crossref

43. Lau MA, Colley L, Willett BR, Lynd LD. Employee’s

preferences for access to mindfulness-based cognitive

therapy to reduce the risk of depressive relapse—a discrete

choice experiment. Mindfulness 2012;3:318-26. Crossref

44. Atisook R, Euasobhon P, Saengsanon A, Jensen MP.

Validity and utility of four pain intensity measures for use

in international research. J Pain Res 2021;14:1129-39. Crossref

45. Yamato TP, Maher CG, Saragiotto BT, Catley MJ,

McAuley JH. The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire:

one or more dimensions? Eur Spine J 2017;26:301-8. Crossref

46. Turk D, Boeri M, Abraham L, et al. Patient preferences for

osteoarthritis pain and chronic low back pain treatments

in the United States: a discrete-choice experiment.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2020;28:1202-13. Crossref

47. Tian X, Yu X, Holst R. Applying the payment card approach

to estimate the WTP for green food in China. In: IAMO

Forum 2011; 2011 Jun 23-24; Halle, Germany; 2011: No.23.

48. Soeteman L, van Exel J, Bobinac A. The impact of the

design of payment scales on the willingness to pay for

health gains. Eur J Health Econ 2017;18:743-60. Crossref

49. Herman PM, Luoto JE, Kommareddi M, Sorbero ME,

Coulter ID. Patient willingness to pay for reductions

in chronic low back pain and chronic neck pain. J Pain

2019;20:1317-27. Crossref

50. Pavel MS, Chakrabarty S, Gow J. Assessing willingness to

pay for health care quality improvements. BMC Health

Serv Res 2015;15:43. Crossref

51. Kanter G, Komesu Y, Qaedan F, Rogers R. 5: Mindfulness-based

stress reduction as a novel treatment for interstitial

cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: a randomized controlled

trial [abstract]. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214(4 Suppl

1):S457-8. Crossref

52. Zhu M, Dong D, Lo HH, Wong SY, Mo PK, Sit RW. Patient

preferences in the treatment of chronic musculoskeletal

pain: a systematic review of discrete choice experiments.

Pain 2023;164:675-89. Crossref

53. UCLA: Statistical Consulting Group. FAQ: How are the

likelihood ratio, wald, and lagrange multiplier (score) tests

different and/or similar? Available from: https://stats.oarc.ucla.edu/other/mult-pkg/faq/general/faqhow-are-the-likelihood-ratio-wald-and-lagrange-multiplier-score-tests-different-andor-similar/#:~:text=The%20log%20likelihood%20(i.e.%2C%20the,model%20with%20a%20likelihood%20function . Accessed 12 May 2024.

54. Hu B, Shao J, Palta M. PSEUDO-R 2 in logistic regression

model. Stat Sin 2006;16:847-60.

55. Sharp D, Lorenc A, Morris R, et al. Complementary

medicine use, views, and experiences: a national survey in

England. BJGP Open 2018;2:bjgpopen18X101614. Crossref

56. Al-Omari B, McMeekin P, Bate A. Systematic review of

studies using conjoint analysis techniques to investigate

patients’ preferences regarding osteoarthritis treatment.

Patient Prefer Adherence 2021;15:197-211. Crossref

57. Poder TG, Beffarat M. Attributes underlying non-surgical

treatment choice for people with low back pain: a

systematic mixed studies review. Int J Health Policy Manag

2021;10:201-10. Crossref

58. Ho EK, Chen L, Simic M, et al. Psychological interventions

for chronic, non-specific low back pain: systematic review

with network meta-analysis. BMJ 2022;376:e067718. Crossref

59. Els C, Jackson TD, Kunyk D, et al. Adverse events

associated with medium- and long-term use of opioids

for chronic non-cancer pain: an overview of Cochrane

Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;10:CD012509. Crossref

60. Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA,

Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain

in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2017;4:CD011279. Crossref