Hong Kong Med J 2024;30:Epub 17 Dec 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Public fertility preservation programme for cancer patients in Hong Kong

Dorothy TY Chan, MB, BS; Jennifer KY Ko, MB, BS, MRCOG; Kevin KW Lam, BSc, PhD; YW Tong, MB, BS, MRCOG; Evelyn Wong, MB, BS, MRCOG; Heidi HY Cheng, MB, BS, MRCOG; Sofie SF Yung, MB, BS, MRCOG; Raymond HW Li, MD, FRCOG; Ernest HY Ng, MD, FRCOG

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, School of Clinical Medicine, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Raymond HW Li (raymondli@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Fertility preservation (FP) offers

cancer patients the opportunity to have biological

children after completing treatment. This study was

performed to review the experience and changes in

service demand since the implementation of a public

FP programme for cancer patients in Hong Kong.

Methods: This retrospective study included men and

women who attended an assisted reproduction unit

for public FP services before cancer treatment from

August 2020 to February 2023. Their medical records

were reviewed and the results were compared with

findings from our previous study to evaluate trends

in service demand.

Results: During the study period, there were 48

consultations for female FP, compared with 72

women who presented for FP from 2010 to 2020 prior

to establishment of the public FP programme. The

median time from referral to consultation was 3 days

(interquartile range [IQR]=2-5). Eighteen women

(37.5%) underwent 19 cycles of ovarian stimulation

for oocyte or embryo cryopreservation. Thirty

women (62.5%) received gonadotropin-releasing

hormone agonists during cancer treatment. There

were 58 consultations for male FP during the study

period, compared with 265 men who presented for

sperm cryopreservation from 2005 to 2020. The median time from referral to consultation was 4

days (IQR=2-7). Fifty-five men (94.8%) attempted

sperm cryopreservation, and 49 (84.5%) successfully

preserved sperm.

Conclusion: Since the establishment of a public

FP programme for cancer patients, there has been

an increase in the demand for FP services at our

centre. Regular review of FP services is warranted

to assess changes in demand and identify areas for

improvement.

New knowledge added by this study

- Since the establishment of a public fertility preservation (FP) programme, there has been an increase in the number of patients seeking FP services at our centre.

- Reproductive-age men seeking FP were more likely than reproductive-age women to undergo gamete cryopreservation.

- Only 62.5% of women received gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists during cancer treatment; the reasons for not receiving the agonists were not recorded.

- The cost of FP may be a barrier to patients considering this option.

- Public funding for medications and gamete storage can support reproductive-age patients in pursuing FP before cancer treatment.

- Further research is needed to improve FP, especially for reproductive-age women.

Introduction

Many individuals are diagnosed with cancer during

childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood.

Worldwide, there were approximately 1 335 100 new

cancer cases among adolescents and young adults

in 20191; the incidence rate was 44.99 per 100 000

people.1 In 2020, the incidence rate for cancer among Hong Kong children and adolescents (aged 0-19

years) was 160 cases per 1 000 000 people.2 There were

177 newly diagnosed cancer cases in this age-group

(92 in male patients and 85 in female patients).2 The

survival rates for childhood and adolescent cancers

are encouraging. In a retrospective cohort study

from a research hospital in the United States,3 the 5-year overall survival rate exceeded 83%. Similarly,

in Hong Kong, the 5-year survival rate among

women diagnosed with breast cancer, the most

common cancer in reproductive-age women, was

84% between 2010 and 2017.2

Chemotherapy or pelvic radiotherapy may

affect fertility, either temporarily or permanently.

Considering advances in cancer treatment and

improved post-treatment survival rates, fertility

should be discussed at the time of cancer diagnosis,

especially for younger patients who have not yet

completed their families. International guidelines

regarding fertility preservation (FP) recommend

that clinicians inform cancer patients about the

potential effects of cancer and its treatment on

reproductive function, as well as FP options.4 5

In a semi-structured phone interview study of

female cancer survivors who were diagnosed with

invasive cervical cancer, breast cancer, Hodgkin

lymphoma, or non-Hodgkin lymphoma at age ≤40

years, participants were interviewed an average of

10 years after diagnosis.6 Those who had wanted

children at the time of diagnosis but were unable

to conceive subsequently reported distress related

to their interrupted fertility.6 Additionally, patients

who do not receive accurate and timely information

regarding FP are at risk for psychological distress.7 In

our recently published cross-sectional questionnaire

study of reproductive-age women in Hong Kong

who had been diagnosed with breast cancer,8 only 44% of those women were aware of FP; however,

46% of the women felt that fertility concerns affected

their cancer treatment decisions.8

The most common FP options include sperm

cryopreservation for men and embryo or oocyte

cryopreservation for women. Other options for

women include pharmacological ovarian protection

using gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)

agonists, ovarian tissue cryopreservation, and

ovarian transposition. In Hong Kong, FP was

previously self-funded and only available through

private services. Sperm cryopreservation costs

approximately HK$4400 to HK$6600 for 2 years,

whereas oocyte and embryo cryopreservation costs

are approximately HK$15 000 to HK$20 000.9 Our

centre launched the first public FP programme for

cancer patients in Hong Kong, beginning in August

2020. Here, we review the two-and-a-half-year

experience of providing public FP services to cancer

patients in Hong Kong.

Methods

This retrospective study included men and women

who attended the Centre of Assisted Reproduction

and Embryology at The University of Hong Kong—Queen Mary Hospital for FP services before cancer

treatment, from the establishment of our public FP

programme in August 2020 until the end of February

2023.

Criteria for public fertility preservation

services

During the study period, we provided public FP for

cancer patients <35 years old, expressed a desire for

future fertility, had a survival rate exceeding 50%

after cancer treatment, had no living children, and

had not undergone prior chemotherapy or pelvic

radiotherapy. In women, an antral follicle count of

>7 on pelvic ultrasound was required. These criteria

were adapted from The Edinburgh Selection Criteria

for ovarian tissue cryopreservation.10

There was no minimum age requirement

for FP. Male adolescents could undergo sperm

freezing if they were able to provide sperm samples

for cryopreservation. For patients aged <18 years,

we included their parents in discussions prior to

proceeding with FP treatment.

During the study period, the public FP

programme offered up to 40 cycles of sperm freezing

and 20 cycles of oocyte/embryo freezing per year.

Referral process

Patients diagnosed with cancer who were expected

to undergo gonadotoxic treatments were referred

to our FP service by surgeons, oncologists,

paediatricians, haematologists, private practitioners,

and cancer support groups. Clinicians completed a referral letter, which can be downloaded from our

centre’s website.11 Patients or their doctors can also

contact us via email. Additionally, a chat group was

established between Hong Kong Children’s Hospital

and our centre to facilitate rapid referrals.

After we received a referral, the patient was

scheduled for an appointment in the public FP clinic

within 1 week. Our centre maintained a flexible

clinic schedule, which allowed urgent cases to be

accommodated within the existing clinic framework,

5 days per week.

Fertility preservation counselling

The details of our FP programme were previously

published.12 Information sheets and videos about

the FP services offered by our centre were readily

accessible to the general population and patients

through our website13 and YouTube channel.14

Patients were encouraged to review these materials

before attending the public FP clinic. For men, sperm

banking was arranged on the same day as counselling.

For women, the options of oocyte and embryo

preservation were discussed if feasible. Embryo

preservation was only offered to women who were

legally married. In Hong Kong, assisted reproductive

technology is regulated by the Human Reproductive

Technology Ordinance.15 This ordinance limits

the storage duration for frozen gametes in cancer

patients to 10 years or until the patient reaches the

age of 55 years, whichever is longer.15 The storage

duration for frozen embryos is limited to 10 years.15

Cryopreserved gametes and embryos can only be

used after a patient recovers from their illness and is

legally married.15 Posthumous use of cryopreserved

gametes and embryos is prohibited.15

The use of GnRH agonists for pharmacological

ovarian protection was discussed either after

cryopreservation or if cryopreservation was not

feasible. Such agonists were usually administered

monthly or every 3 months during chemotherapy.

The characteristics of men who underwent

sperm cryopreservation and women who underwent

ovarian stimulation for oocyte or embryo

cryopreservation were prospectively entered into

our database. Medical records (both in paper and

electronic formats), including data from the assisted

reproductive technology database at our centre

and the Hospital Authority’s electronic clinical

management system, were retrieved and reviewed.

These records encompassed demographic data,

cancer type, cancer treatment, FP method chosen,

ovarian stimulation cycle characteristics, semen

analysis, reproductive outcomes, and follow-up

information, if available.

All women who attended our centre for FP

were asked to return to our late-effects clinic for

gonadal function monitoring after the completion

of cancer treatment. All men were asked to undergo semen analysis when they wished to conceive after the completion of cancer treatment.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS (Windows version

26; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States) and are

presented as median (interquartile range [IQR]) or

as number (percentage). P value was calculated by

Chi squared test.

Methods

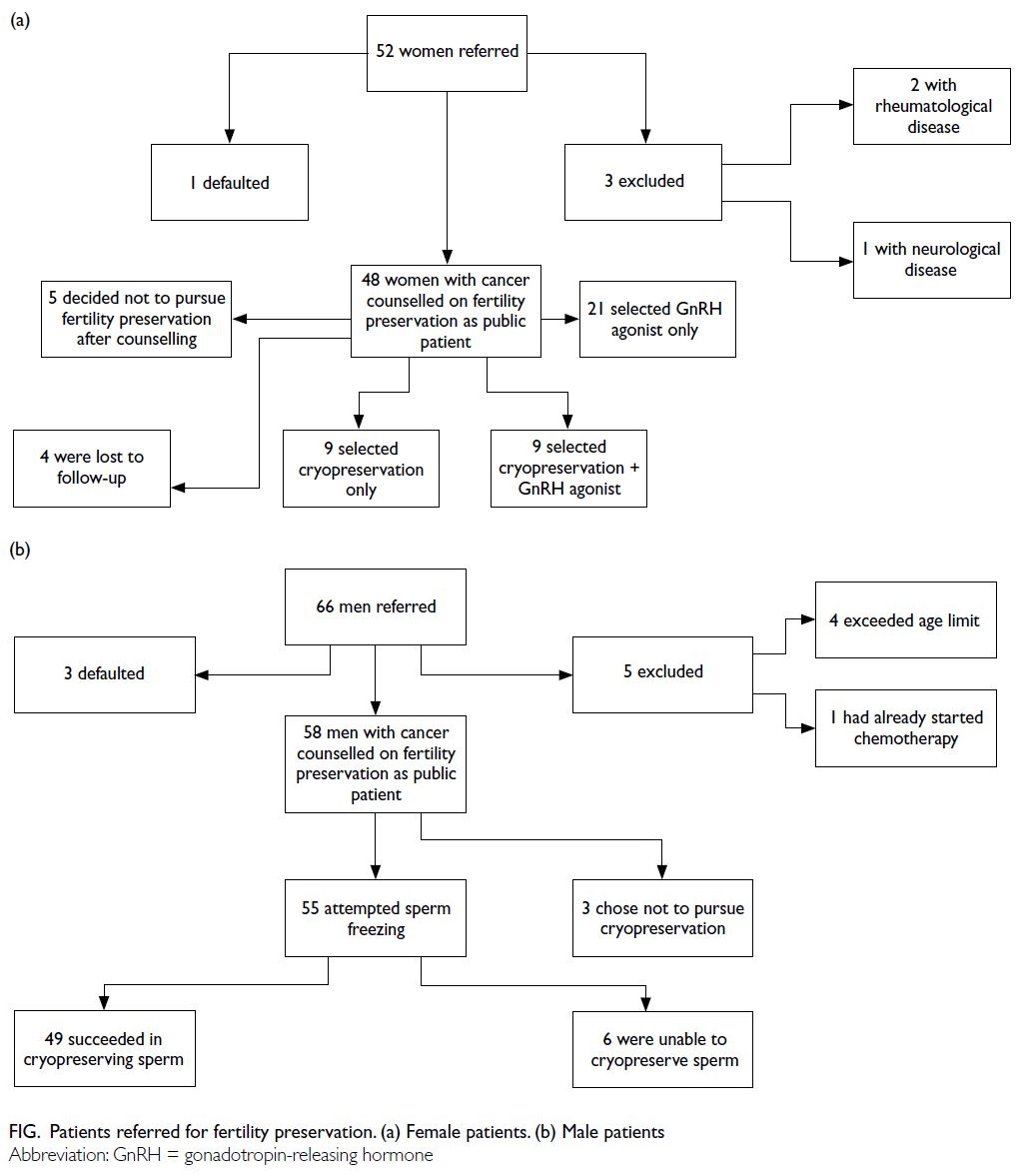

Women

Fifty-two women were referred to our public FP

clinic between August 2020 and February 2023.

Three women were excluded from the analysis

because they had non-malignant conditions,

including rheumatological disease (systemic lupus

erythematosus) and neurological disease (multiple

sclerosis). Additionally, one woman missed her clinic

appointment. Therefore, the final analysis included

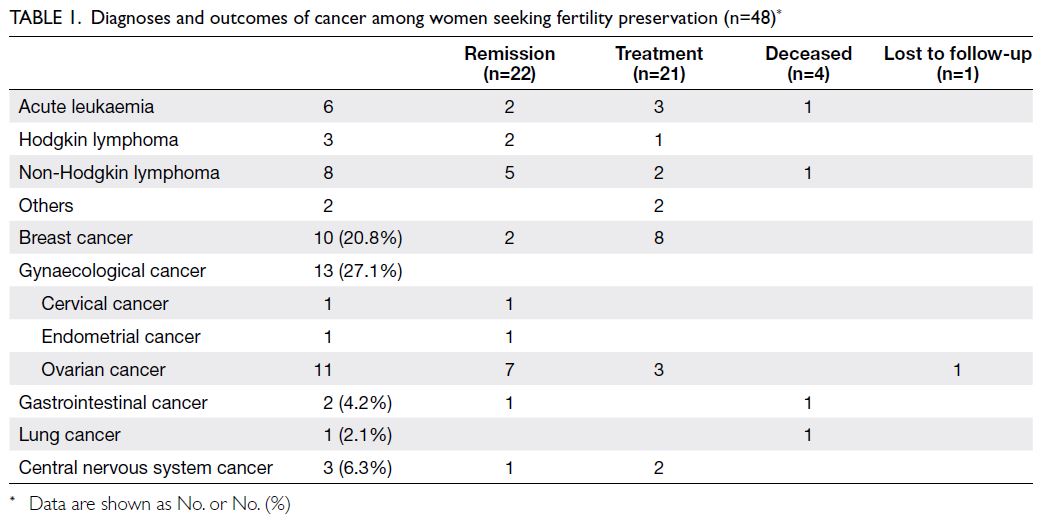

48 women (Fig a). The median age of these women

was 30 years (IQR=25-33). The cancer outcomes

of these women are shown in Table 1. Regarding

marital status, 36 women (75.0%) were single, 11

(22.9%) were married, and one (2.1%) was divorced.

All were nulliparous, except for one married woman

(2.1%) with a livebirth was ineligible for publicly

funded FP due to the programme’s criteria. She then

selected GnRH agonist treatment after counselling.

The median time from referral to consultation was 3

days (IQR=2-5).

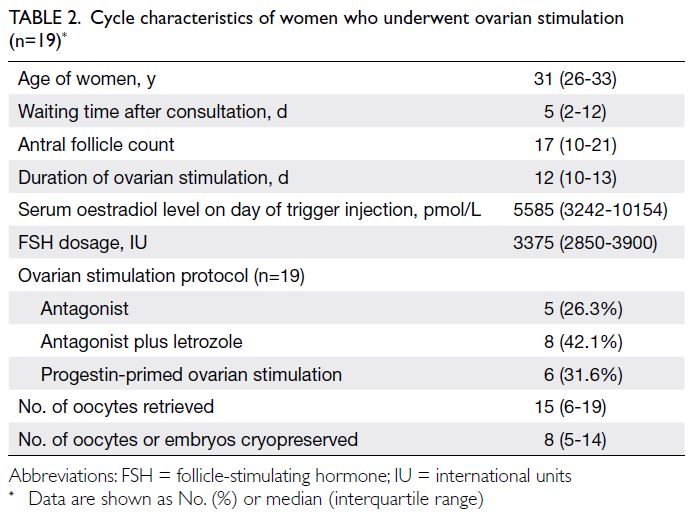

Eighteen women underwent 19 cycles

of ovarian stimulation for oocyte or embryo

cryopreservation (Table 2). One woman underwent

an additional self-financed stimulation cycle because

she only achieved two frozen oocytes in the first

cycle. She achieved two additional frozen oocytes in

the second attempt. Thirteen women cryopreserved

oocytes, whereas five women cryopreserved embryos

(three at the cleavage stage and two at the blastocyst

stage). The median time between consultation and

ovarian stimulation was 5 days (IQR=2-12) [Table 2].

All women with breast cancer received letrozole co-treatment

during ovarian stimulation.

One woman developed moderate ovarian

hyperstimulation syndrome requiring hospital

admission. Oocyte retrieval was uneventful, and

45 oocytes were retrieved. However, 3 days after

oocyte retrieval, she was admitted with abdominal

distension, shortness of breath, and vomiting.

She was diagnosed with moderate ovarian

hyperstimulation syndrome, which resolved with

conservative management.

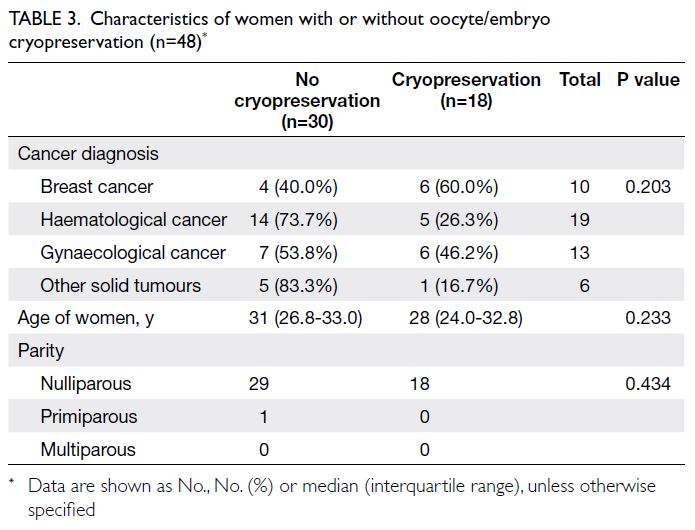

There was no significant age difference

between women who proceeded with oocyte/embryo cryopreservation and those who did not. The median age of women who proceeded with oocyte/embryo cryopreservation was 28 years (IQR=24.0-32.8), whereas the median age of women who did not proceed with oocyte/embryo cryopreservation was

31 years (IQR=26.8-33.0) [Table 3].

Among patients with breast and gynaecological

cancers, six of 10 (60.0%) and six of 13 (46.2%)

underwent oocyte/embryo cryopreservation,

respectively, compared with five of 19 (26.3%)

women with haematological cancers and one of six

(16.7%) women with other solid tumours (Table 3).

Among the 48 women who attended the clinic, nine (18.8%) proceeded with oocyte or embryo cryopreservation alone, nine (18.8%) underwent

cryopreservation followed by the use of GnRH

agonists, 21 (43.8%) received GnRH agonists alone,

five (10.4%) decided against FP after counselling, and

four (8.3%) were lost to follow-up. Those who chose

GnRH agonists received this treatment from their

primary oncology team.

At the end of February 2023, among the 48

women, 22 exhibited disease remission, 21 were

continuing treatment, four were deceased, and one had been lost to follow-up (Table 1). None of the

women have returned to use their frozen oocytes or

embryos, nor have any reported natural conception

since their cancer diagnosis.

Men

Sixty-six men were referred to our public FP clinic during the study period (Fig b). Five men were

excluded: four had exceeded the age limit and one had

already begun chemotherapy. Fertility preservation

counselling at a private clinic was offered to those

who were not eligible for the public FP service.

One man, who exceeded the age limit, underwent

self-funded sperm cryopreservation. Three men

missed their clinic appointments. Therefore, the

final analysis included 58 men (Fig b). The median

age of the men was 26 years (IQR=18.3-32.8). The

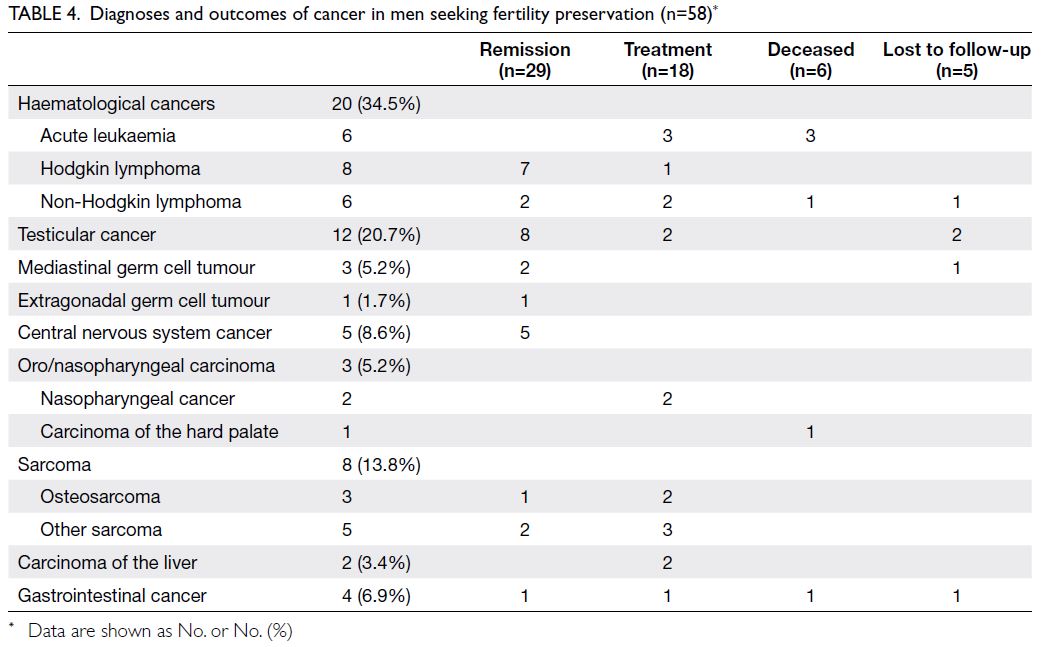

cancer outcomes of these men are shown in Table 4.

Regarding marital status, 51 men (87.9%) were single

and seven men (12.1%) were married. One man

(1.7%) had a child but was unmarried. The remaining

57 men (98.3%) had no offspring. The median time

from referral to consultation was 4 days (IQR=2-7).

Among the 58 men who attended the clinic,

55 attempted sperm freezing and three chose not to

undergo cryopreservation after counselling. Six men

were unable to cryopreserve sperm (Fig b). One,

aged 14 years, was unable to provide a semen sample;

four men submitted semen samples containing no

sperm. One man had previously attempted sperm

cryopreservation at a private hospital, but no

sperm were found in his ejaculate. He subsequently

underwent testicular sperm extraction at our

hospital; no sperm were retrieved. The ages of the

men with no sperm in their semen ranged from 15

to 34 years.

The median number of vials of cryopreserved

sperm was 5 (IQR=5-5) and the median sperm

concentration was 18.8 million/mL (IQR=4.3-52.8).

At the end of February 2023, among the

58 men, 29 exhibited disease remission, 18 were

continuing treatment, six were deceased, and five

had been lost to follow-up (Table 4). None of the

men have returned to use their frozen sperm.

As of this writing, six men and four woman

who attended the FP clinic have died.

Discussion

This is the first review of a public FP programme for

cancer patients in Hong Kong. Our study showed that among the 48 women who attended during

the study period, 37.5% (n=18) underwent oocyte/embryo cryopreservation and 62.5% (n=30) chose GnRH agonists for FP. In contrast, among the 58

men who attended for FP before cancer treatment,

>90% attempted sperm cryopreservation.

We previously published a review of our self-funded

FP service from 2010 to 2020.12 During

that period, 72 women attended consultations for FP, and 20 of them underwent 22 cycles of ovarian

stimulation for oocyte or embryo cryopreservation.12

Additionally, from 1995 to 2020, 265 men underwent

sperm cryopreservation.12 Over the years, there were

increases in the numbers of men and women seeking

FP; the increase was more prominent among women.

For comparison, we selected the period from

2018 to 2020 (ie, the 2.5 years immediately preceding

the launch of the public FP programme). During that

period, 19 women were referred for self-funded FP

prior to cancer treatment, and 10 (52.6%) underwent

oocyte or embryo cryopreservation. Fifty-eight

men were referred for FP and underwent sperm

cryopreservation. In the years prior to the launch

of the publicly funded FP programme, we had

already begun networking with various specialties,

which likely contributed to the gradual increase in

awareness and demand for FP services.

Public fertility preservation programme

A successful FP programme requires good

networking, flexibility, and a patient-friendly clinic

environment. During the establishment of the public

FP programme, we have networked with other

specialties to enhance collaboration. Our centre

aimed to simplify logistics so that consultations

could be arranged as quickly as possible, allowing FP

counselling and procedures to be completed within

the short window of opportunity before cancer

treatment. In our public FP clinic, the median waiting

times from referral to consultation were 3 days for women and 4 days for men. Among women who chose

oocyte or embryo cryopreservation, the median time

from consultation to the start of ovarian stimulation

was 5 days (IQR=2-12). In our previous study, the

time from consultation to oocyte retrieval was 17

days (IQR=13-30).12 Notably, our previous study

did not investigate the waiting time from referral to

consultation; therefore, direct comparisons cannot

be performed. Compared with our previous study

regarding FP for cancer patients at our centre,12 the

proportion of women who ultimately underwent

oocyte or embryo cryopreservation increased from

28% to 38% in the public FP programme. However,

further monitoring is needed to determine whether

this difference represents a true upward trend due to

increased awareness and easier access to the service.

Additionally, patient characteristics and cancer

types may vary across time periods.

For reproductive-age women with cancer, the

receipt of specialised counselling regarding fertility

issues, followed by FP, has been linked to less regret

and improved quality of life among survivors.16

Providing our patients with accessible FP counselling

and affordable treatments is an essential aspect of

comprehensive oncology care. A clinical practice

guideline from the American Society of Clinical

Oncology indicates that FP should be initiated as

early as possible in the treatment process to allow

for the widest range of options.17 Referral to FP

services enables patients to receive counselling from

reproductive medicine specialists, empowering

them to make informed decisions about fertility

treatment.

At our FP clinic, patients were able to consult

reproductive medicine specialists who discussed the

potential effects of gonadotoxic cancer treatments

on future fertility and described FP options. Local

regulations concerning gamete storage and assisted

reproduction were also explained. Patients were

informed that they must be legally married to use

frozen gametes in the future, and that gametes

cannot be used posthumously.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists

In our cohort, only 62.5% of women received

GnRH agonists during cancer treatment; the

reasons for not receiving GnRH agonists were

not recorded. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone

agonists are usually administered monthly or

every 3 months during cancer treatment, although

their effectiveness depends on the type of cancer

treatment. Some studies of breast cancer patients

have shown that GnRH agonists can reduce the risk

of premature ovarian insufficiency, but the fertility

benefit remains uncertain.18 19 20 Most studies have

focused on outcomes such as the maintenance

or resumption of menstruation, prevention of

treatment-related premature ovarian failure, and ovulation. In a Cochrane review20 which discussed

randomised controlled trials that examined the

effect of GnRH analogues for chemotherapy-induced

ovarian failure in premenopausal women, 12

randomised controlled trials were included. Eleven

studies reported rates of menstruation recovery or

maintenance, four studies measured treatment-related

premature ovarian failure, and seven studies

reported the rates of pregnancy.20 However, there

are limited data regarding live birth rates.20 A

meta-analysis of randomised studies concerning

ovarian suppression using GnRH agonists during

chemotherapy in breast cancer patients found that

temporary ovarian suppression with a GnRH agonist

in young breast cancer patients was associated with

a reduced risk of chemotherapy-induced premature

ovarian insufficiency; it also appeared to increase

the pregnancy rate without negatively influencing

prognosis.21 Thus far, the benefit of GnRH agonists

in other malignancies is unclear. A long-term

analysis of young female lymphoma patients showed

that GnRH agonists were not effective in preventing

chemotherapy-induced premature ovarian

insufficiency and did not improve future pregnancy

rates.22 According to the European Society of Human

Reproduction and Embryology guideline on female

FP,4 GnRH agonists should be offered as an option

for protecting ovarian function in premenopausal

breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy;

importantly, limited evidence exists regarding

their protective effects on ovarian reserve and

potential future pregnancies.4 In malignancies other

than breast cancer, GnRH agonists should not be

routinely offered as an option for protecting ovarian

function protection and FP without discussing

the uncertainty of their benefit.4 Gonadotropin-releasing

hormone agonists during chemotherapy

should not be considered as a substitute for

established FP techniques, such as cryopreservation.

They can be offered in addition to cryopreservation

or when such techniques are not feasible.4 Despite

the use of GnRH agonists, patients may experience

premature ovarian insufficiency. Gonadotropin-releasing

hormone agonists are currently provided

as a self-financed option; women are often referred

back to their oncology team, who prescribes and

administers these agonists after FP counselling.

The proportion of patients who underwent oocyte/embryo cryopreservation was higher among those

with gynaecological or breast cancers than among

those with haematological malignancies. This

difference is likely due to the nature of their diseases

and the urgency of initiating cancer treatment.

Oocyte or embryo cryopreservation

For women who chose to proceed with ovarian

stimulation for oocyte or embryo cryopreservation,

oocytes were retrieved during a stimulated cycle. Recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone could

be initiated on any day of the menstrual cycle for

ovarian stimulation (ie, ‘random-start’), using either

a GnRH antagonist or progestin-primed protocol.

This random-start approach allowed ovarian

stimulation without substantial delays and did not

affect the number or quality of retrieved oocytes.4

For women with hormone-sensitive cancers (eg,

breast cancer), letrozole was routinely used during

ovarian stimulation. The concomitant use of

letrozole reduced circulating oestrogen levels and

did not impair the efficacy of ovarian stimulation.23

A systematic review and meta-analysis regarding

the safety of hormonal stimulation in young women

with breast cancer before starting cancer treatment,

as well as survivors who underwent assisted

reproduction after cancer treatment, showed

no increased risk of breast cancer recurrence in

women who underwent ovarian stimulation with

concomitant letrozole treatment.24 Despite using

the ‘random-start’ approach, one cycle of ovarian

stimulation required approximately 2 weeks.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. It was a retrospective,

single-centre study conducted over a short period

of time; thus, it may not reflect situations in other

regions. Due to resource constraints, we only

included cancer patients who had not begun cancer

treatment. Patients who did not meet the criteria for

the public FP programme but still wished to pursue

FP were referred to private clinics or other private

centres upon receipt of their referral and therefore

were excluded from this review. Patients who had

already begun cancer treatment were also excluded

from the public FP service. However, they could still

be referred to our centre after stabilisation to assess

fertility and explore self-funded FP options before

undergoing more toxic chemotherapy, non–fertility-sparing

radiotherapy, or surgeries. At the time of

writing, our centre has not yet offered ovarian or

testicular tissue cryopreservation. A 2018 survey of

several Asian countries (eg, Australia, China, and

India) revealed that ovarian tissue cryopreservation

was available for prepubertal girls and postpubertal

women who were unable to delay the initiation of

chemotherapy.25 Testicular tissue cryopreservation

also was provided to prepubertal boys in Australia,

China, India, Indonesia, Japan, and Taiwan.25 A recently

published pilot study from Hong Kong demonstrated

the feasibility of ovarian tissue cryopreservation and

transplantation using xenografts in nude mice26;

ovarian tissue cryopreservation has recently become

available in Hong Kong.

The patients included in this study were

counselled for FP, and many are still undergoing

cancer treatment and monitoring; none have returned to use the stored material. They were

advised to return after cancer treatment for follow-up

regarding their gonadal function. Patient

satisfaction should also be evaluated. However, at

the time of cryopreservation—typically close to

the time of cancer diagnosis—patients may feel

overwhelmed by the diagnosis and planned cancer

treatments. Thus, patient satisfaction may be more

accurately evaluated when the cancer is controlled

or in remission.

Future outlook

Despite the presence of the public FP programme,

patients were required to pay for the medications

used in ovarian stimulation, as well as the fees

involved in oocyte handling, freezing, and storage

of frozen gametes or embryos; these costs were

considerably reduced compared with expenses in

private clinics. Cost remains a major barrier to

accessing FP services. Although a public healthcare

system has been established in Hong Kong, cancer

patients are often financially overwhelmed due to

the loss of income after a cancer diagnosis, along

with additional expenditures for various self-funded

investigations or treatments. We recently performed

a survey of the knowledge, attitudes, and intentions

regarding FP among breast cancer patients; most

participants thought that FP should be subsidised by

the government or provided at no cost.8

Conclusion

Since the establishment of a public FP programme

for cancer patients, there has been an increase in

the number of patients seeking FP services. More

than 90% of men attempted sperm cryopreservation,

whereas 37.5% of women underwent oocyte/embryo

cryopreservation and 62.5% of women received

GnRH agonists during cancer treatment. With

further promotion, changes in funding policies,

and a more accessible FP programme, the demand

for FP services is expected to increase. Fertility

preservation services should be regularly reviewed

to assess changes in demand and identify areas for

improvement.

Author contributions

Concept or design: JKY Ko, EHY Ng.

Acquisition of data: DTY Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: DTY Chan, JKY Ko, EHY Ng.

Drafting of the manuscript: DTY Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: DTY Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: DTY Chan, JKY Ko, EHY Ng.

Drafting of the manuscript: DTY Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review

Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority

Hong Kong West Cluster, Hong Kong (Ref No.: UW 23-334).

The requirement for informed consent was waived by the

Board due to the retrospective nature of the research.

References

1. You L, Lv Z, Li C, et al. Worldwide cancer statistics of

adolescents and young adults in 2019: a systematic analysis

of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. ESMO Open

2021;6:100255. Crossref

2. Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital Authority. Overview

of Hong Kong Cancer Statistics of 2020. Available

from: https://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/pdf/overview/Overview%20of%20HK%20Cancer%20Stat%202020.pdf. Accessed 7 May 2023.

3. Bhakta N, Liu Q, Ness KK, et al. The cumulative burden

of surviving childhood cancer: an initial report from

the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE). Lancet

2017;390:2569-82. Crossref

4. ESHRE Guideline Group on Female Fertility Preservation;

Anderson RA, Amant F, et al. ESHRE guideline:

female fertility preservation. Hum Reprod Open

2020;2020:hoaa052. Crossref

5. Practice Committee of the American Society for

Reproductive Medicine. Fertility preservation in patients

undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: a

committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2019;112:1022-33. Crossref

6. Canada AL, Schover LR. The psychosocial impact of

interrupted childbearing in long-term female cancer

survivors. Psychooncology 2012;21:134-43. Crossref

7. Rosen A, Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Rosenzweig L.

Psychosocial distress in young cancer survivors. Semin

Oncol Nurs 2009;25:268-77. Crossref

8. Ko JK, Cheung CS, Cheng HH, et al. Knowledge, attitudes

and intention on fertility preservation among breast cancer

patients. Sci Rep 2023;13:9645. Crossref

9. Yeung SY, Ng EY, Lao TT, Li TC, Chung JP. Fertility

preservation in Hong Kong Chinese society: awareness,

knowledge and acceptance. BMC Womens Health

2020;20:86. Crossref

10. Wallace WH, Smith AG, Kelsey TW, Edgar AE,

Anderson RA. Fertility preservation for girls and young

women with cancer: population-based validation of

criteria for ovarian tissue cryopreservation. Lancet Oncol

2014;15:1129-36. Crossref

11. Centre of Assisted Reproduction and Embryology, The

University of Hong Kong–Queen Mary Hospital. How to

make an appointment. Available from: https://hkuivf.hku.hk/en/services/fertility-preservation/how-to-make-an-appointment/. Accessed 27 Nov 2024.

12. Ko JK, Lam KK, Cheng HH, et al. Fertility preservation

programme in a tertiary-assisted reproduction unit in

Hong Kong. Fertil Reprod 2021;3:94-100. Crossref

13. Centre of Assisted Reproduction and Embryology, The

University of Hong Kong–Queen Mary Hospital. Fertility

preservation. Available from: https://hkuivf.hku.hk/en/services/fertility-preservation/. Accessed 27 Nov 2024.

14. Centre of Assisted Reproduction and Embryology, The

University of Hong Kong–Queen Mary Hospital. YouTube

Channel. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/@HKUIVF. Accessed 27 Nov 2024.

15. Hong Kong e-Legislation, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Cap 561 Human Reproductive Technology Ordinance.

Available from: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap561!en-zh-Hant-HK. Accessed 27 Nov 2024.

16. Letourneau JM, Ebbel EE, Katz PP, et al. Pretreatment

fertility counseling and fertility preservation improve

quality of life in reproductive age women with cancer.

Cancer 2012;118:1710-7. Crossref

17. Oktay K, Harvey BE, Partridge AH, et al. Fertility

preservation in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical

practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1994-2001. Crossref

18. Blumenfeld Z. Fertility preservation using GnRH

agonists: rationale, possible mechanisms, and explanation

of controversy. Clin Med Insights Reprod Health

2019;13:1179558119870163. Crossref

19. Zong X, Yu Y, Yang H, et al. Effects of gonadotropin-releasing

hormone analogs on ovarian function

against chemotherapy-induced gonadotoxic effects in

premenopausal women with breast cancer in China: a

randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2022;8:252-8. Crossref

20. Chen H, Xiao L, Li J, Cui L, Huang W. Adjuvant

gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues for the

prevention of chemotherapy-induced premature ovarian

failure in premenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev 2019;3:CD008018. Crossref

21. Lambertini M, Ceppi M, Poggio F, et al. Ovarian

suppression using luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone

agonists during chemotherapy to preserve ovarian function

and fertility of breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis of

randomized studies. Ann Oncol 2015;26:2408-19. Crossref

22. Demeestere I, Brice P, Peccatori FA, et al. No evidence for

the benefit of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist

in preserving ovarian function and fertility in lymphoma

survivors treated with chemotherapy: final long-term

report of a prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol

2016;34:2568-74. Crossref

23. Moravek MB, Confino R, Lawson AK, et al. Predictors

and outcomes in breast cancer patients who did or did

not pursue fertility preservation. Breast Cancer Res Treat

2021;186:429-37. Crossref

24. Arecco L, Blondeaux E, Bruzzone M, et al. Safety of fertility

preservation techniques before and after anticancer

treatments in young women with breast cancer: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod 2022;37:954-68. Crossref

25. Takae S, Lee JR, Mahajan N, et al. Fertility preservation for

child and adolescent cancer patients in Asian countries.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:655. Crossref

26. Chung JP, Chan DY, Song Y, et al. Implementation of

ovarian tissue cryopreservation in Hong Kong. Hong Kong

Med J 2023;29:121-31. Crossref