© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PERSPECTIVE

Adapting selected international paediatric asthma guidelines for use in Hong Kong

KL Hon, MB, BS, MD1; Daniel KK Ng, MB, BS, MD2; WK Chiu, MB, BS, MRCPCH3; Alexander KC Leung, MB, BS, FRCPC4; DH Chen, MD5; WH Leung, MB, BS, MD6

1 Department of Paediatrics, CUHK Medical Centre, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Paediatrics, The Hong Kong Sanitorium & Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Department of Pediatrics, The University of Calgary and The Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, Canada

5 The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China

6 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof KL Hon (ehon@hotmail.com)

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory airway disease

characterised by variable and recurring symptoms,

episodic reversible airflow obstruction, and easily

triggered bronchospasm.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A combination of

environmental and genetic factors contributes to its

onset. Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation,

response to bronchodilators and inhaled

corticosteroids (ICS), and spirometric pulmonary

function test results.9 Asthma is classified according

to symptom frequency, forced expiratory volume

in 1 second (FEV1), peak expiratory flow (PEF), and

atopic versus non-atopic aetiology. Symptoms can

be prevented by avoiding triggers and suppressed

through the use of ICS.2 7 8 10

We previously conducted an extensive review of

eight widely accepted and implemented guidelines11;

however, management approaches vary across these

guidelines. These international guidelines provide

valuable recommendations for managing childhood

asthma, especially in many Asian cities where unified

national guidelines are unavailable.11

This article offers practical insights into current

recommendations for the management of childhood

asthma, specifically focusing on diagnosis, severity

classification, treatment options, and asthma

control. We reviewed the following guidelines from

selected countries and organisations in Asia, the

United States, the United Kingdom, the European

Union, and Australasia:

(1) the Chinese guidelines 201612 13;

(2) the Chinese Children’s Asthma Action Plan consensus 202014 15;

(3) Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines 20218 16;

(4) the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NAEPP-NHLBI) Updates 202017;

(5) the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society 2020 guidelines18;

(6) the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2021 guidelines19;

(7) the joint British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2019 guidelines20;

(8) the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Biologicals Guidelines 202021; and

(9) the Australian Asthma Handbook of the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand National Asthma Committee (TSANZ/NAC).22

(2) the Chinese Children’s Asthma Action Plan consensus 202014 15;

(3) Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines 20218 16;

(4) the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NAEPP-NHLBI) Updates 202017;

(5) the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society 2020 guidelines18;

(6) the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2021 guidelines19;

(7) the joint British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2019 guidelines20;

(8) the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Biologicals Guidelines 202021; and

(9) the Australian Asthma Handbook of the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand National Asthma Committee (TSANZ/NAC).22

Diagnosis

Many of the reviewed guidelines are similar to the

GINA8 16 and NICE guidelines.1 5 8 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 According to

the guidelines, clinical diagnosis of asthma is based

on the acquisition of a supporting history, physical

examination findings, and the results of relevant

investigations. Notably, several guidelines do not rely

on the supporting history and physical examination

components.17 18 21

The guidelines generally agree with some but

not all of the clinical and objective approaches to

diagnosing childhood asthma described by NICE.19

According to the GINA guidelines,8 the utility of

fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) in confirming

or ruling out a diagnosis of asthma has not been

established.

According to a subset of these major

guidelines,1 5 several conclusions can be drawn. A

clinical diagnosis of asthma should be considered

in children presenting with recurring or episodic

symptoms such as wheezing, breathlessness, cough,

and/or chest tightness without an alternative

explanation. Spirometry is recommended for all

patients with suspected asthma to confirm the

diagnosis, assess the severity of airflow limitation,

and monitor asthma control. Bronchodilator

reversibility can be assessed with a peak flow

meter. Importantly, the presence of bronchodilator

reversibility is neither diagnostic of asthma nor

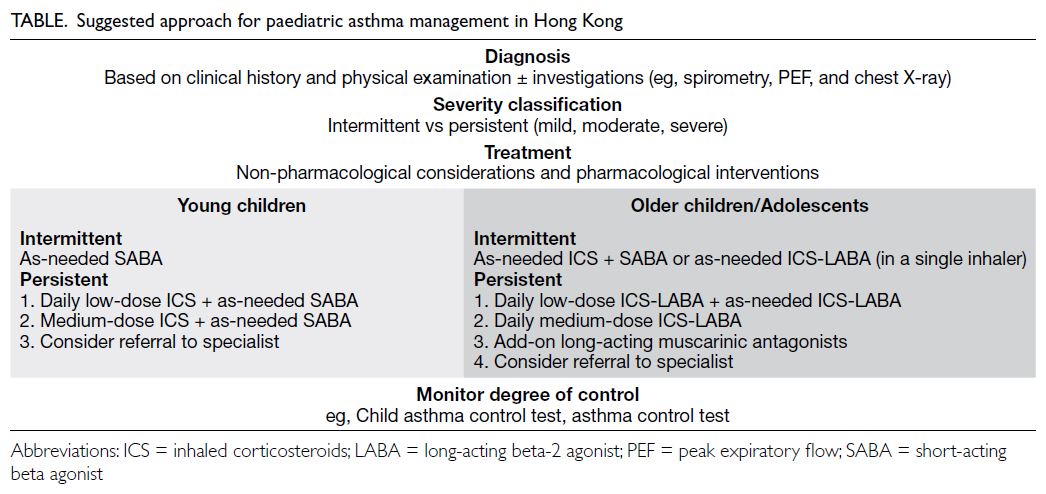

sufficient to rule it out.8 16 23 We propose a concise

reference of paediatric asthma management for local

practitioners (Table).

Severity

Classification of asthma severity is generally

recommended,1 5 8 12 13 14 15 16 18 20 21 22 except by the NAEPP-NHLBI17

and NICE guidelines.19 Asthma severity

is typically classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

According to the GINA guidelines,8 asthma severity

is not a static state and may change over time and is

currently assessed retrospectively based on the level

of treatment required for symptom and exacerbation

control. On the other hand, the NHLBI classifies

severity as intermittent or persistent and mild,

moderate, or severe.1 24

Treatment

Treatment comprises both pharmacological

and non-pharmacological interventions.1 5 8 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22

Pharmacological interventions are similar across

guidelines, with specific recommendations for young

children and older children/adolescents. Notably,

the GINA8 and the Chinese guidelines12 13 14 are similar

in this regard. The GINA guidelines16 recommend

short-acting beta agonists (SABAs) as needed for

symptom relief across all management steps. Short

courses of oral corticosteroids may be necessary

for patients presenting with severe uncontrolled

asthma. The NAEPP-NHLBI guidelines5 17 24 also

recommend SABAs as needed for symptom relief

across all management steps. Stepwise management

for asthma differs according to age-group in the joint

British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate

Guidelines Network20 and the TSANZ/NAC

guidelines.22 Similarly, the NICE guidelines19

recommend distinct stepwise management for

asthma according to age-group.

Treatment for adolescents is outlined in two

‘Tracks’ within the GINA guidelines.16 Track 1,

using ICS-formoterol for symptom relief, is the preferred approach. Track 2, utilising SABAs for

symptom relief, is a recommended alternative if

Track 1 is not feasible or preferred by a patient

who has not experienced exacerbations with their

current therapy.16 The guideline for children aged

6 to 11 years has been updated to include low-dose

budesonide-formoterol for maintenance and relief

therapy.16

The NAEPP-NHLBI 2020 guideline also

includes focused updates.2 17 Among children aged 0

to 4 years, a short course of daily ICS, rather than

as-needed SABAs, is recommended at the onset of a

respiratory tract infection.2 9 17 Among children aged

≥12 years with uncontrolled persistent asthma, the

addition of long-acting beta-2 agonist (LABA) to

ICS therapy is preferred over the addition of long-acting

muscarinic antagonists, as recommended by

the Chinese guidelines.12 13 14 The use of sublingual

immunotherapy for childhood asthma is not generally

recommended due to insufficient evidence.8 9 12 13 14 19 24

Inhaled corticosteroids are the preferred

controller medication for management of stable

asthma. Most of the clinical benefit from ICS

therapy is achieved at low to moderate doses.

Inhaled corticosteroids should be started at a low

to moderate dose (depending on initial symptom

severity) and used at the lowest possible effective

dose. High-dose ICS use should ideally be avoided

to minimise the risks of local and systemic side-effects.

Long-acting beta-2 agonist monotherapy

should not be used for stable asthma. The addition

of LABA to ICS therapy is preferred when symptoms

remain uncontrolled despite moderate doses of ICS

monotherapy.11

Leukotriene modifiers have no role in the

management of acute asthma. Monotherapy with

leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs) may be

an acceptable alternative to ICS for patients with mild asthma who are unwilling or unable to receive

ICS therapy.8 16 The addition of LTRAs might benefit

patients whose asthma remains uncontrolled despite

ICS/LABA combination therapy.8 16 25 Tiotropium

may be considered as an add-on treatment if asthma

remains uncontrolled on moderate-to-high-dose

ICS/LABA combination therapy.18 Methylxanthine

monotherapy is less effective compared to ICS alone.

Short-acting beta agonists are the preferred

rescue medications for asthma. Short-acting

muscarinic antagonists are less preferred as

alternatives or add-ons to SABA for symptom

relief. Formoterol monotherapy for relief should

be avoided due to safety concerns associated with

LABA monotherapy. Oral beta 2 agonists are not

recommended for rescue use. It is preferable to

consider single-inhaler therapy, incorporating an

ICS/LABA combination (formoterol-based) for both

maintenance and relief purposes.11

Rapid-acting inhaled beta-2 agonists (eg,

salbutamol) are the preferred bronchodilators

for managing acute exacerbations of asthma.

The combination of ipratropium bromide with

salbutamol results in better bronchodilation than

either medication alone. Ipratropium should be

administered to all patients experiencing severe

exacerbations of asthma (eg, 500 μg once then 250 μg

every 4-6 hours). Metered-dose inhalers with spacers

are comparable to nebulisers for managing acute

asthma. Nebulisers require higher doses and have

greater potential for side-effects. Among patients

unable to use a metered-dose inhaler with a spacer,

medications can be delivered through a nebuliser.

After a patient has been stabilised, they should be

switched from a nebuliser to a spacer. Continuous

nebulisation (2.5 mg salbutamol every 15 minutes

or >4 nebulisations per hour) of rapid-acting SABAs

is better than intermittent nebulisation (2.5 mg

salbutamol every 20 minutes or ≤3 nebulisations per

hour). Subsequent doses of nebulised salbutamol

should be 2.5 mg every 2 to 4 hours, depending

on the clinical response. Formoterol offers no

additional benefit over salbutamol; therefore, it is

not recommended for routine use in patients with

acute asthma.11

Systemic glucocorticoids should be

administered to all patients with severe acute

asthma. The oral route is as effective as the parenteral

route, except in critically ill patients and in patients

with contraindications to enteral feeding. For most

patients, daily doses of glucocorticoids equivalent

to 1 to 2 mg/kg of prednisolone for 5 to 7 days are

sufficient. Systemic steroids can be discontinued

without tapering if administered for <3 weeks. In

cases of non-severe exacerbation, patients should

first receive an increased dose of inhaled SABA

(4-6 puffs of 100 μg salbutamol every 30 minutes). If

there is no response within 1 hour, oral prednisone (1-2 mg/kg) once daily for 5 to 7 days should be

initiated. Inhaled corticosteroids do not offer

added benefits when combined with systemic

corticosteroids and are thus not recommended for

acute asthma treatment.11

Omalizumab may be considered as adjunct

to ICS in patients with moderate to severe asthma,

characterised by elevated serum immunoglobulin

E (IgE) levels and a positive skin test result for at

least one perennial aeroallergen.26 Single-allergen

immunotherapy may provide modest benefits

to patients with mild-to-moderate asthma and

a skin allergy to that specific antigen. However,

multiple-allergen immunotherapy is not currently

recommended due to lack of evidence.

The NICE guideline also recommends other

therapeutic interventions for asthma management,

including oxygen therapy, traditional Chinese

medicine, breathing exercises, and vitamin D

supplementation.19 However, there is no consensus

among guidelines regarding non-pharmacological

management options,19 21 particularly in terms

of prevention/self-management and alternative

therapies. Alternative therapies are not generally

recommended. Trigger avoidance, patient

education, adolescent-to-adult care transition,

lifestyle modifications, and asthma action plans are

recommended.19 21

Monitoring control

Monitoring of asthma control is generally

recommended,1 5 8 12 13 14 15 16 17 19 20 22 except in the European

Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society

202018 and European Academy of Allergy and

Clinical Immunology 2020 guidelines.21 Asthma

control should be classified as either adequate or

inadequate, considering daytime symptoms (or

rescue medication use), nighttime symptoms/awakening, activity limitations, and the results of

pulmonary function tests (eg, PEF or FEV1 value).

Spirometry or PEF variability assessment is

generally recommended, but there is no agreement

regarding specific thresholds.8 12 13 14 According to the

GINA guidelines,8 diurnal PEF variability of >13% in

children are considered excessive. If a patient’s FEV1

value falls within the predicted normal range during

symptom presentation, it is less likely that those

symptoms are attributable to asthma. However,

patients with a baseline FEV1 value >80% of the

predicted value can experience clinically significant

improvement in lung function with bronchodilator

or controller treatment. Predicted normal ranges

(especially for PEF) have limitations because no such

ranges have been established in children. Therefore,

the GINA guidelines recommend using the patient’s

own best reading as their ‘normal’ value.8 12 13 14

According to the Chinese guidelines and

recommendations, continuous monitoring of FeNO can help assess asthma control and guide

the development of an optimal asthma treatment

regimen.12 13 14 15 School-age children are generally

able to cooperate with the sputum induction

test procedure.8 12 13 14 Continuous monitoring of

induced sputum eosinophil count may be useful

to assess asthma control and guide optimisation of

management.8 12 13 14

Asthma management may require adjustments

to medication regimens through a control-based

cycle approach that involves timely treatment

escalation and de-escalation, along with regular

monitoring. Treatment escalation is indicated if

control is not achieved after reviewing patient

adherence, inhaler technique, and trigger control.19

Treatment de-escalation can be considered when

symptoms have been well-controlled for at least 3

months (as per the Chinese,12 13 14 15 NAEPP-NHLBI,17

and NICE guidelines19)5 24 or 6 months (with close

supervision within 4-6 weeks as per the TSANZ/NAC guidelines).22 Asthma control assessment is a

key component of asthma care. For children, self-monitoring

using an asthma diary is recommended

only by the Chinese12 13 and GINA guidelines.8 16

Peak expiratory flow measurements should

not be substituted for FEV1 measurements. Patient

self-monitoring of PEF is recommended to facilitate

better asthma control. Routine bronchoprovocation

testing is not recommended for diagnosing

asthma. However, methacholine challenge can

be utilised to rule out asthma as a differential

diagnosis, particularly when spirometry results are

normal. While chest radiographs are not routinely

recommended for patients with suspected asthma,

they may be considered if an alternative diagnosis or

asthma-related complication is suspected.24

Quantification of the eosinophil count in

sputum (<2% is considered normal while >2%

indicates eosinophilic inflammation) can guide

ICS therapy, potentially minimising the risk of

exacerbations in adults with moderate-to-severe

asthma.24

Routine measurement of FeNO is not

recommended in asthma management. Similarly,

routine assessments of allergic status, eg,

measurements of total IgE level, measurements

of IgE level specific to different environmental

allergens, and skin prick tests, are not recommended

for diagnosing and managing asthma.24

Oxygen saturation should be assessed using

pulse oximetry for all patients presenting with an

acute asthma attack. Non-severe exacerbations

usually do not require additional investigations.

Patients with a PEF <60% of predicted or personal

best should receive care in the emergency

department. Patients with oxygen saturation

levels <92% should be managed in the emergency

department or hospital ward and should undergo further investigation through arterial blood gas

analysis. Oxygen should only be administered to

hypoxaemic patients; it should be titrated to maintain

oxygen saturation level to stay between 93% and

95%. The absence of pulse oximetry or arterial blood

gas data should not preclude oxygen administration.

In patients requiring oxygen flow rates >8 L/min,

partial pressure of carbon dioxide should be closely

monitored.24

Pulmonary rehabilitation improves asthma

symptoms and quality of life, and significantly

improve exercise capacity. Pretreatment with

bronchodilator agents (SABAs, short-acting

muscarinic antagonists, and LABAs), as well as anti-inflammatory

agents (LTRAs but not ICS), is effective

in attenuating the reduction of FEV1 associated with

exercise-induced asthma.8 16 27 Regular use of ICS or

LTRAs is effective in preventing exercise-induced

asthma.27

Smoking cessation should be recommended

for all asthma patients who smoke. Optimal self-management

of asthma, involving patient education,

self-monitoring, regular physician review, and a

written asthma action plan, is recommended.

Conclusion

Despite the recent comprehensive update of the

GINA guidelines in 2023,28 29 it remains impractical

to fully adhere to these guidelines or any other

single set of guidelines in both public and private

paediatric healthcare settings within Hong Kong due

to multiple pragmatic issues.

Asthma is a heterogeneous syndrome

encompassing many underlying causes and patient

characteristics, along with varying degrees of

mucus hypersecretion, airway hyperreactivity, and

inflammation.30 A severity classification should be

established to guide treatment. Current clinical

management aims for disease control, including

symptom control, risk reduction, and prevention

of severe exacerbations. A personalised treatment

strategy, with inhaler therapy as the core, which

titrates airway inflammation and bronchodilation

therapies according to symptoms and objective

asthma assessments, should benefit most patients

with asthma. It can be difficult, if not impossible, for

general practitioners and paediatricians to follow

these guidelines due to various constraints, including

the availability of diagnostic tools, the need to

incorporate patient preferences, and the frequency

of guideline updates. For example, the latest update

to the GINA 2024 report was published on 22

May 2024 to clarify some medication doses.31 The

maintenance and as-needed use of ICS-formoterol,

as proposed by the GINA8 16 31 and NICE guidelines,19

offers a simple, flexible, and safe treatment option

for patients with asthma and clinicians. Short-acting

beta agonists with or without ICS remain the preferred treatment for young children. However,

inhaler therapy adherence, steroid phobia, and

mistrust of Western medicine remain important

health issues for patients with asthma and their

families.32

Guidelines should not be rigidly followed;

factors such as resources, family attitudes,

and compliance must be considered. In-depth

counselling and the establishment of good rapport

are key components to successful management of

this prevalent and challenging disease in Hong Kong.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design, acquisition

of the data, analysis or interpretation of the data, drafting of

the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for

important intellectual content. All authors had full access to

the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version

for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and

integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KL Hon was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Agarwal R, Dhooria S, Aggarwal AN, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of bronchial asthma: joint ICS/NCCP (I) recommendations. Lung India 2015;32(Suppl 1):S3-42. Crossref

2. Lee DL, Baptist AP. Understanding the updates in the asthma guidelines. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2022;43:595-612. Crossref

3. Gupta RS, Weiss KB. The 2007 National Asthma Education and Prevention Program asthma guidelines: accelerating their implementation and facilitating their impact on children with asthma. Pediatrics 2009;123 Suppl 3:S193-8. Crossref

4. Khan L. Overview of the updates for the management of asthma guidelines. Pediatr Ann 2022;51:e132-5. Crossref

5. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120(5 Suppl):S94-138. Crossref

6. Urbano FL. Review of the NAEPP 2007 Expert Panel Report (EPR-3) on Asthma Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines. J Manag Care Pharm 2008;14:41-9. Crossref

7. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National

Institutes of Health, United States Department of Health

and Human Services. National Asthma Education and

Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for

the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma—Full Report

2007. 2007 Aug 28. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/media/docs/EPR-3_Asthma_Full_Report_2007.pdf. Accessed 29 Nov 2024.

8. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma

Management and Prevention—Updated 2011. 2011. Available from: https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/2011-GINA.pdf. Accessed 29 Nov 2024.

9. Lemans RF Jr, Busse WW. Asthma: clinical expression and molecular mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125(2 Suppl 2):S95-102. Crossref

10. Boulet LP, FitzGerald JM, Reddel HK. The revised 2014 GINA strategy report: opportunities for change. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2015;21:1-7. Crossref

11. Hon KL, Ng DK, Chiu WK, Leung AK. Insights from overviewing selective international guidelines for pediatric asthma. Curr Pediatr Rev 2024 Jan 29. Epub ahead of print. Crossref

12. Subspecialty Group of Respiratory Diseases, Society of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association; Editorial Board, Chinese Journal of Pediatrics. Guideline for the diagnosis and optimal management of asthma in children (2016) [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 2016;54:167-81. Crossref

13. Hong J, Bao Y, Chen A, et al. Chinese guidelines for childhood asthma 2016: major updates, recommendations and key regional data. J Asthma 2018;55:1138-46. Crossref

14. Zhang B, Jin R, Guan RZ, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of Chinese Children's Asthma Action Plan on the long-term management of children with asthma at home [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2020;100:3702-5. Crossref

15. Zhu K, Xiang L, Shen K. Efficacy of Chinese Children's Asthma Action Plan in the management of children with asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc 2020;41:e3-10. Crossref

16. Reddel HK, Bacharier LB, Bateman ED, et al. Global Initiative for Asthma Strategy 2021: executive summary and rationale for key changes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022;10:S1-18. Crossref

17. Expert Panel Working Group of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) administered and coordinated National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee (NAEPPCC); Cloutier MM, Baptist AP, et al. 2020 focused updates to the asthma management guidelines: a report from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee Expert Panel Working Group. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020;146:1217-70. Crossref

18. Holguin F, Cardet JC, Chung KF, et al. Management of severe asthma: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline. Eur Respir J 2020;55:1900588. Crossref

19. Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma

management; NICE guideline [NG80]. London: National

Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Updated

2021 Mar 22. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80. Accessed 29 Nov 2024.

20. Healthcare Improvement Scotland, United Kingdom.

British guideline on the management of asthma: a national

clinical guideline. Jul 2019 (revised). Available from:

https://digirepo.nlm.nih.gov/master/borndig/101772271/sign158.pdf. Accessed 9 Feb 2025.

21. Agache I, Akdis CA, Akdis M, et al. EAACI Biologicals Guidelines-recommendations for severe asthma. Allergy 2021;76:14-44. Crossref

22. National Asthma Council. Australian Asthma Handbook.

Available from: https://www.asthmahandbook.org.au/. Accessed 1 Mar 2023.

23. Tan DJ, Lodge CJ, Lowe AJ, et al. Bronchodilator reversibility as a diagnostic test for adult asthma: findings from the population-based Tasmanian Longitudinal Health Study. ERJ Open Res 2021;7:00042-2020. Crossref

24. Mammen JR, McGovern CM. Summary of the 2020 focused updates to U.S. asthma management guidelines: what has changed and what hasn't? J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2021;34:238-41. Crossref

25. Sadatsafavi M, Lynd L, Marra C, Bedouch P, Fitzgerald M.

Comparative outcomes of leukotriene receptor antagonists

and long-acting β-agonists as add-on therapy in asthmatic

patients: a population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol

2013;132:63-9. Crossref

26. Lin CH, Cheng SL. A review of omalizumab for the

management of severe asthma. Drug Des Devel Ther

2016;10:2369-78. Crossref

27. Grzelewski T, Stelmach I. Exercise-induced

bronchoconstriction in asthmatic children: a comparative

systematic review of the available treatment options. Drugs

2009;69:1533-53. Crossref

28. Venkatesan P. 2023 GINA report for asthma. Lancet Respir

Med 2023;11:589. Crossref

29. Levy ML, Bacharier LB, Bateman E, et al. Key

recommendations for primary care from the 2022 Global

Initiative for Asthma (GINA) update. NPJ Prim Care

Respir Med 2023;33:7. Crossref

30. Pavord ID, Beasley R, Agusti A, et al. After asthma:

redefining airways diseases. Lancet 2018;391:350-400. Crossref

31. Global Initiative for Asthma. 2024 GINA Main Report.

Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention.

2024. Available from: https://ginasthma.org/2024-report/. Accessed 29 Nov 2024.

32. Ip KI, Hon KL, Tsang KY, Leung TN. Steroid phobia, Chinese medicine and asthma control. Clin Respir J 2018;12:1559-64. Crossref