© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Suyin Han and medical practice in the early 1950s Hong Kong

TW Wong, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)

Members, Education and Research Committee, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

Suyin Han (韓素音, 1917–2012) was a renowned

doctor and author. Her 1952 novel A Many-Splendoured Thing was adapted into an Oscar-winning

Hollywood movie Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing, bringing her worldwide fame. The story depicts the love affair between a female doctor

and a male war correspondent in Hong Kong during

1949 and 1950.1

Han was born Rosalie Matilda Kuanghu Chou

(周光瑚) in Henan, China in 1917 to a railway

engineer father and a Belgian mother. She was known

as Elizabeth Tang after marrying Paohuang Tang,

a Kuomintang military officer, in 1938. While in

London for her husband’s work as a military attaché

to the United Kingdom, Han attended the Royal

Free Hospital School of Medicine. Paohuang Tang

died in 1947 during the civil war in China. Upon

receiving her medical degree from the University of

London the following year, Han wished to move to

Hong Kong to be close to China.2 Serendipitously,

she was introduced to Prof Gordon King, then head

of obstetrics and gynaecology at The University of

Hong Kong, who was visiting London at the time. He

secured her a job in Hong Kong.

Between 1949 and 1952, Han worked at Queen

Mary Hospital, an experience she drew on for her

autobiography My House Has Two Doors. The book

contains vivid descriptions of the medical landscape

in the early post-war era when Hong Kong was

flooded with refugees from the mainland.

In her first role at the hospital as an assistant

in the obstetrics and gynaecology department,

Han worked alongside Dr Daphne Chun (who later

succeeded Prof King as the first local professor),

whom Han greatly admired:

‘Daphne’s hands were a marvel; tiny and so

able, so nimble! She was quite happy operating all

day, and I both envied and resented her enthusiasm,

the beam upon her face when yet another belly had to

be opened…’3

Gynaecological work was somewhat different

in those days:

‘Many a young girl is still brought to me to be

examined before marriage. Many times a week I

write a certificate beginning: “I...certify this girl to be

a virgin.”’4

Realising gynaecology was not her vocation, Han joined the pathology department as a

demonstrator, working under Prof Pao-chang Hou,

in February 1950 (Fig). She was assigned to study

liver pathology and observed the professor’s work.

‘As for Hou Paochang, there was ecstasy upon

his face as he plunged his hands into a corpse and

palpated an unsuspected cancer.’5

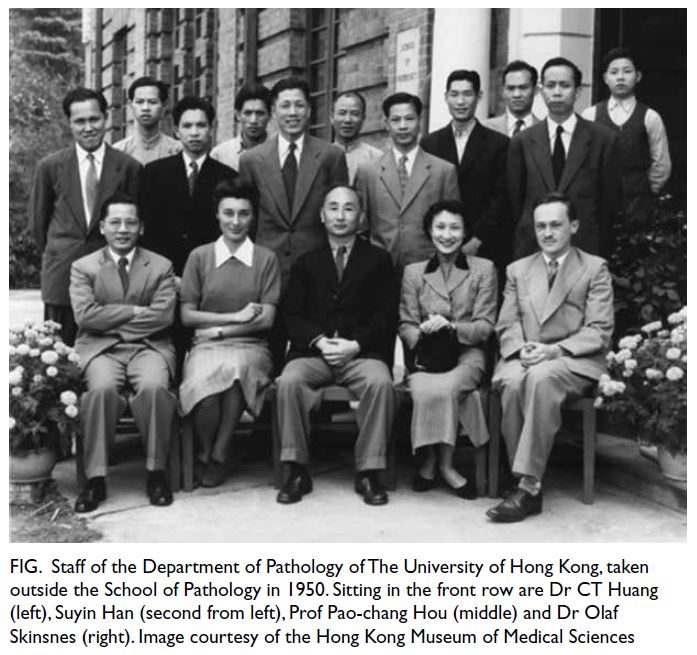

Figure. Staff of the Department of Pathology of The University of Hong Kong, taken outside the School of Pathology in 1950. Sitting in the front row are Dr CT Huang (left), Suyin Han (second from left), Prof Pao-chang Hou (middle) and Dr Olaf Skinsnes (right). Image courtesy of the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences

‘The livers we examined were very often gorged

with flukes…Like a stream of swimmers the grey-brown

parasites came lizarding down when we

opened gall bladders and bile ducts, and Hou would

wade in joyfully with gloved hands shouting, “Ha, ha”.

He was looking for possible cancerous or precancerous

changes due to the flukes, since liver cancer was also

very prevalent in the fluke-infested regions of South

China.’6

Leprosy was prevalent then. Dr Olaf Skinsnes

(Fig), who was destined to teach in China, joined the

pathology department in 1949 as he was stranded

in Hong Kong. There, he began his research on the

pathology and immunology of leprosy, eventually

becoming an international expert in the disease. He

co-founded the Hay Ling Chau Leprosarium.7

‘In that winter, lepers were batted back and

forth across the border with China. The Chinese

pushed them into Hong Kong; they were found,

brought to hospital, certified lepers, pushed back

across the border.’8

Han changed track again in May 1950 when the

post of casualty officer fell vacant. She applied for two

reasons: first, she wanted to return to clinical work

and second, the benefits included a government flat.

She was appointed women’s assistant medical officer

in July and oversaw the casualty department despite

being a junior doctor with no prior experience. Prof

David Todd, then an intern recruited to cover after-office

hours, recalled Han typing furiously in her

office between patients.9

The rapid influx of refugees kept the casualty

department busy with around 90 cases a day.

Infections, particularly pulmonary tuberculosis,

were common.

Everything came to Casualty. Rare cases of

leprosy, lupus, tetanus, enlarged spleen from long-term

malarias, syphilitics, tuberculous meningitis

(mostly children and very common in Hong Kong),

accidents and suicides, homicides, fishermen blown up by the dynamite they used for fishing, early cancers

and late cancers, pneumonias and jaundices and

brain abscesses and the insane…Everything uncanny,

impossible and fantastic came to Casualty.’10

Reflecting some of the population’s low socio-economic

status, there were many critically ill

children brought in too late.

‘It was a child, wrapped in layers of clothing. We

undid the layers, and the abdomen appeared. There

was practically nothing else but glistening abdomen,

enormously distended, semi-transparent, netted in

a lace pattern of veins, looking as if at any moment

it might burst like an overblown balloon. Around

the navel were a dozen of those round brown marks,

like owls’ eyes, which the Chinese herbalist burns

through slices of ginger root with a wax wick, to draw

out the sickness. Above this monstrous sphere sat the

chest, a tiny bird’s cage; then the face of a miniature

querulous monkey, the blind wide eyes bleak with

dying. “How long has it been ill?” And the invariable

answer: “Oh, a long, long time...” “Then why did you

not come earlier?” And again, the same answer as

always: “M’chee...we did not know…The baby died in

the lift, on the way to the Babies’ Ward.”’11

In those days, operation of the casualty

department depended on dressers (male nurses),

whom Han held in high regard.

‘The dressers of Casualty were seasoned men

with tremendous experience…they knew far more

than many young doctors, and they also knew how

to save lives…They were cheerful, devoted and

immensely courteous to the patients.’10

What did Han think about her job as a casualty officer?

‘Casualty work was exactly what I could

do. Though looked down upon by more snobbish

housemen in medicine and surgery (because Casualty

did not lead to better jobs, it was a dead-end), it was

for me occasion for my talent in diagnosis.’10

In 1952, Han married Leonard F Comber, a British officer in the Malayan Special Branch. The church ceremony was attended by eminent guests,

including Governor Sir Alexander Grantham and Dr

Kok-cheang Yeo, director of medical services, and

the bride was given away by Prof Lindsay Ride.12 The

couple moved to Johor Bahru in Malaysia, where

she worked as a general practitioner for roughly 10

years before devoting herself full-time to writing.

She later relocated to Switzerland and died there in

Lausanne in 2012. Her legacy lives on through her

books, which continue to find new readers around

the world.

References

1. Han S. A Many-Splendoured Thing. London: Jonathan Cape; 1952.

2. Stafford N. Han Suyin. Family doctor, author, and a bridge between China and the West [obituary]. BMJ 2013;346:e8667. Crossref

3. Han S. My House Has Two Doors. London: Triad Grafton Books; 1980: 19.

4. Han S. A Many-Splendoured Thing. London: Penguin Books; 1959: 222.

5. Han S. My House Has Two Doors. London: Triad Grafton Books; 1980: 36.

6. Han S. My House Has Two Doors. London: Triad Grafton Books; 1980: 38.

7. Hastings RC. Olaf K. Skinsnes 1917-1997. Int J Lepr 1998;66:243-4.

8. Han S. A Many-Splendoured Thing. London: Penguin Books; 1959: 188.

9. Todd D. Foreword. Hong Kong J Emerg Med 1994;1:i.

10. Han S. My House Has Two Doors. London: Triad Grafton Books; 1980: 48.

11. Han S. A Many-Splendoured Thing. London: Penguin Books; 1959: 192.

12. Society Wedding: Dr Elizabeth Tang and Mr Francis Comber. South China Morning Post. 1952 Feb 2.