© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Factors affecting human papillomavirus vaccine acceptance among parents of Primary 4 to 6 boys and girls in Hong Kong

Jody KP Chu, MClinPharm1; CW Sing, PhD1; Y Li, BPharm1; Patrick H Wong, BSc2; Eric YT So, MPH2; Ian CK Wong, PhD1,3

1 Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Merck Sharp and Dohme (Asia) Ltd, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Research Department of Practice and Policy, School of Pharmacy, University College London, London, United Kingdom

Corresponding author: Ms Jody KP Chu (chukpj@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Human papillomavirus (HPV) poses a

substantial but underestimated healthcare burden in

Hong Kong. This study investigated factors affecting

parental acceptance of HPV vaccination after

the introduction of an immunisation programme

for primary school girls. We assessed parental

perceptions and related factors concerning HPV

vaccination for both boys and girls.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional survey

between December 2021 and February 2022 among

parents of Primary 4 to 6 students in Hong Kong.

Our self-administered online survey collected

data regarding socio-demographic characteristics,

awareness and knowledge of HPV vaccination,

attitudes towards HPV vaccination, and acceptance

of HPV vaccination. Characteristics were compared

between boys’ parents and girls’ parents. Factors

associated with vaccine acceptance were analysed by

multivariate logistic regression.

Results: We observed high awareness of HPV

vaccination among boys’ parents and girls’

parents; however, they demonstrated relatively

poor knowledge of HPV and the HPV vaccine. An

alarming low HPV vaccination uptake rate was also

observed. Attitudes towards the HPV vaccine were

similar between parent groups. A majority of parents

believed that the HPV vaccine was safe and effective

in preventing infection. Parents of boys showed lower HPV vaccine acceptance. Factors associated

with acceptance differed between parent groups.

Conclusion: High awareness of HPV and HPV

vaccine is predictive of vaccine acceptance. Boys’

parents are less likely to accept HPV vaccination

and emphasis should be placed on addressing

potential HPV vaccine hesitancy in this group.

Public education should also aim to raise awareness

of government vaccination programme, and

implementation of catch-up vaccination programme

to school children beyond primary school should be

considered.

New knowledge added by this study

- Awareness of human papillomavirus (HPV) was similar between parents of boys and parents of girls (P=0.346); 81.4% of boys’ parents and 78.5% of girls’ parents had heard of HPV.

- Overall, attitudes towards HPV and the HPV vaccine were similar between parents of boys and parents of girls.

- High acceptance of their child receiving the HPV vaccine in both parents of boys and girls was observed; parents of girls were more likely to accept the vaccine, compared with parents of boys (89.7% vs 73.8%; P<0.001).

- The awareness of the HPV vaccination programme among girls’ parents is low, echoing the problem of insufficient information provision concerning HPV vaccination, especially during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

- To prevent future healthcare burdens caused by immunisation gaps, catch-up vaccination services for affected children should be considered and implemented as soon as possible.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a common sexually

transmitted infection that constitutes a substantial global healthcare burden. It is associated with genital

warts and various cancers (eg, cervical, penile, anal,

oropharyngeal, and head and neck cancers). Human papillomavirus causes 4.5% (630 000) of all new

cancer cases worldwide.1

In Hong Kong, cervical cancer is the ninth

most common cancer, with a crude incidence of 12.9

per 100 000 women and girls.2 3 There are limited

data regarding HPV infection or HPV-associated

cancers in men and boys. A local study estimated

that the incidence of genital warts in Hong Kong was

203.7 per 100 000 person-years. Men and boys had

a higher incidence compared with women and girls

(292.2 per 100 000 person-years vs 124.9 per 100 000

person-years, respectively), suggesting a similar or

possibly higher prevalence of HPV infection in men

and boys.4

Human papillomavirus vaccination is a

highly effective preventive measure against HPV

infection and its complications. National HPV

vaccination programmes targeting adolescent girls

have significantly reduced the incidences of HPV-associated

diseases.5 The World Health Organization

recommends including HPV vaccination in routine

programmes for girls aged 9 to 14 years, with possible

extension to boys if feasible.6

Universal HPV vaccination programmes,

covering both adolescent boys and adolescent girls,

have become increasingly common in recent years,

particularly in developed countries such as the

United States, Canada, Australia, and 20 European

nations. Female-only vaccination programmes with

high vaccine coverage rates have demonstrated

substantial public health impact concerning several

HPV-related diseases and cancers.7 Gender-neutral

vaccination programmes, targeting both boys and

girls, have shown greater resilience8 and faster

elimination of cervical cancer9; they also provide

direct protection to reduce disease burden in all men

and in subpopulations of men (eg, men who have

sex with men and men who have sex abroad).10 11 12

The achievement of an 80% vaccination rate in both

sexes is expected to enable the elimination of HPV

subtypes 6, 11, 16, and 18.13

Despite the benefits of a high vaccination rate,

the current rate of HPV vaccine is much lower than

desired. In Hong Kong, the rate of vaccine uptake

reportedly ranged from 2.2% to 7.2% in adolescent

girls and 0.6% in adolescent boys before the HPV

vaccine was incorporated into the Hong Kong

Childhood Immunisation Programme (HKCIP).14 15 16

The 9-valent HPV vaccine was introduced into the

Programme for Primary 5 and 6 girls, with a reported

first-dose uptake rate of 85% among Primary 5 girls

in 2020.17 However, vaccination rates are expected to

remain low among adolescent boys.

Prior to the inclusion of HPV vaccination in the

HKCIP, few local studies explored parental decision-making14 15 16 18; those that did primarily focused on

girls, with limited examination of factors influencing

vaccine acceptance or uptake. One survey did include parents of adolescent boys but was hindered by its

small sample size (162 boys’ parents).14 Considering

the recent implementation of the HPV vaccination

programme for primary school girls and the lack

of sufficient data concerning HPV vaccination in

Hong Kong, further local research is warranted. An

understanding of parental acceptance, particularly

for boys, can inform strategies to improve vaccine

uptake.

This study aimed to identify factors affecting

HPV vaccination acceptance among Hong Kong

parents of Primary 4 to 6 students. It compared

the knowledge, attitudes, and acceptance between

girls’ parents and boys’ parents, then explored the

underlying reasons for their vaccination decisions.

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional survey was conducted from

December 2021 to February 2022. Invitation letters

were sent to 554 primary schools in Hong Kong,

including public local schools, private local schools,

and Direct Subsidy Scheme schools. In total, 65

schools agreed to participate. After consent had

been obtained from participating schools, parents

of Primary 4 to 6 students at those schools received

a self-administered online survey through the

Qualtrics platform.

Measures

The survey was divided into four sections, namely, (1) socio-demographic characteristics, (2) awareness and knowledge regarding HPV and HPV vaccination,

(3) attitudes towards HPV vaccination, and (4)

acceptance of HPV vaccination. The questionnaires

were available in both English and Chinese (online supplementary Appendices 1 and 2, respectively).

A detailed description of the survey sections is

provided in online supplementary Appendix 3. Upon

completion of the online survey, the results were

stored in the Qualtrics platform for further analysis.

Data analysis

Human papillomavirus vaccination attitudes were

measured using a five-point Likert scale. Two

statements (Questions 41 and 42) with strong

internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=0.81) were

combined to form the variable ‘Worried about

HPV infection’, and the mean score of the two

statements was used for analysis. Similarly, two

other statements (Questions 46 and 47) with strong

internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=0.91) were

merged into the variable ‘Worried that HPV vaccine

might negatively impact child’s sexual activity’.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterise

the participants and study variables. The first analysis

compared the knowledge, attitudes, and acceptance

of the HPV vaccine between boys’ parents and girls’

parents. Significant differences between groups were

identified using the Chi squared test for nominal

variables, the t test for continuous variables, and

the Mann-Whitney U test for ordinal variables (age-group,

household income, and education level).

In the second analysis, we investigated factors

associated with the acceptance of HPV vaccination

for children. Participants whose children had

already received HPV vaccination were excluded

from the analysis due to missing values in some

variables (Questions 49 to 51). Univariate logistic

regression was used to estimate the crude odds ratio

(OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). The study

variables were included as independent predictors;

the acceptance of HPV vaccination for children was

regarded as a binary dependent variable (‘Yes’ or

‘No’). Variables with P values <0.1 were entered into

multivariate logistic regression. P values <0.05 were

considered statistically significant.

Because free HPV vaccination was only

provided for primary school girls in Hong Kong,

we assumed that factors affecting the acceptance of

HPV vaccination for their child varied between boys’

parents and girls’ parents. Consequently, the second

analysis was conducted separately for each parent

group.

All analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.1.1).

Results

In total, 844 participants completed the survey.

Of these, 43.8% were parents of boys and 56.2%

were parents of girls. The socio-demographic

characteristics of the parents are presented in Table 1.

Vaccine uptake rate

The HPV vaccine uptake rate is low with boys’ parents reported 6.8% and girls’ parents reported

4.9%. Among children who have received HPV

vaccine, >90% of parents in both groups reported

that their children received the HPV vaccine through

the HKCIP (Table 1).

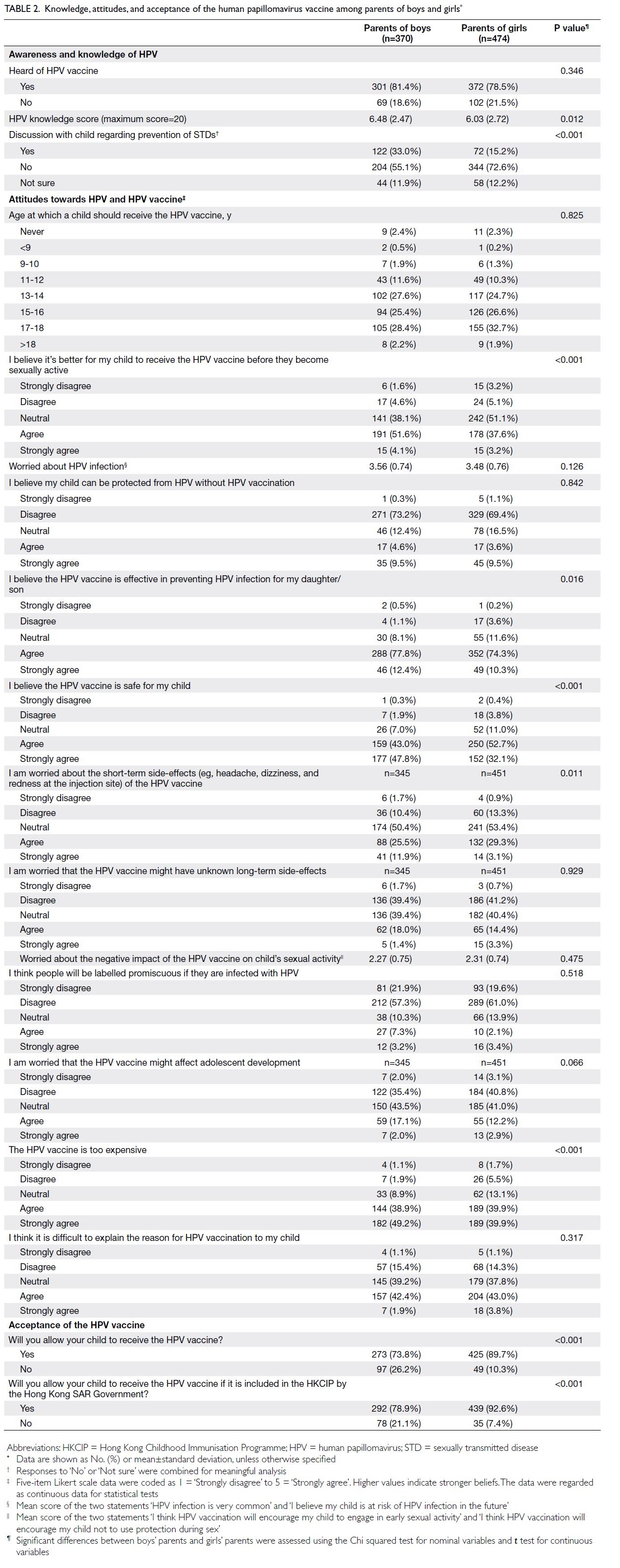

Awareness and knowledge of human papillomavirus and the vaccine among parents

Awareness of HPV was similar between boys’

parents and girls’ parents (81.4% vs 78.5%; P=0.346).

Knowledge scores regarding HPV and the HPV

vaccine were low in both parent groups; parents of

boys had higher mean scores compared with parents

of girls (6.48 vs 6.03; P=0.012). More boys’ parents

discussed sexually transmitted disease (STDs) with

their children, relative to girls’ parents (33.0% vs

15.2%; P<0.001) [Table 2].

Table 2. Knowledge, attitudes, and acceptance of the human papillomavirus vaccine among parents of boys and girls

Attitudes towards the vaccine in parents

Two questions addressed the timing of vaccination,

namely: ‘At what age should a child receive the

HPV vaccine?’, and the yes/no statement ‘I believe

it’s better for my child to receive the HPV vaccine

before they become sexually active’. A majority of

parents, both of boys (83.6%) and of girls (85.9%),

believed that their children should receive the HPV

vaccine at age ≥13 years. Additionally, more parents

of boys (55.7%) believed that their children should

receive the HPV vaccine before becoming sexually

active; more parents of girls (51.1%) reported a

neutral perspective on this statement. Regarding

HPV infection and HPV vaccine effectiveness,

parents in both groups were worried about HPV

infection (mean±standard deviation [SD] out of

5: 3.56±0.74 in boys’ parents; 3.48±0.76 in girls’

parents). Over 70% in parents of both groups believe

that their children cannot be protected from HPV

without HPV vaccination, furthermore a majority of

parents in both groups also believe in the vaccine’s

effectiveness (90.2% in boys’ parents and 84.6% in

girls’ parents) [Table 2].

Concerning vaccine safety, impacts, and cost,

most parents of boys (90.8%) and parents of girls

(84.8%) agreed that the HPV vaccine is safe. They

had a neutral perspective or were less worried

about the vaccine’s short-term (62.5% and 67.6%, respectively) and long-term side-effects (80.5% and 82.3%, respectively) [Table 2].

Additionally, parents had a neutral

perspective or were less worried about the vaccine’s

negative impacts or influence on adolescent

development. However, most parents agreed that

the HPV vaccine is too expensive (88.1% and 79.8%,

respectively) [Table 2].

Vaccine acceptance in parents of boys and girls

We observed high acceptance of the HPV vaccine

for their children in boys’ parents (73.8%) and girls’

parents (89.7%). If the HPV vaccine were subsidised

under the HKCIP, acceptance in parents would

slightly increase because the government would cover

the cost (78.9% and 92.6%, respectively) [Table 2].

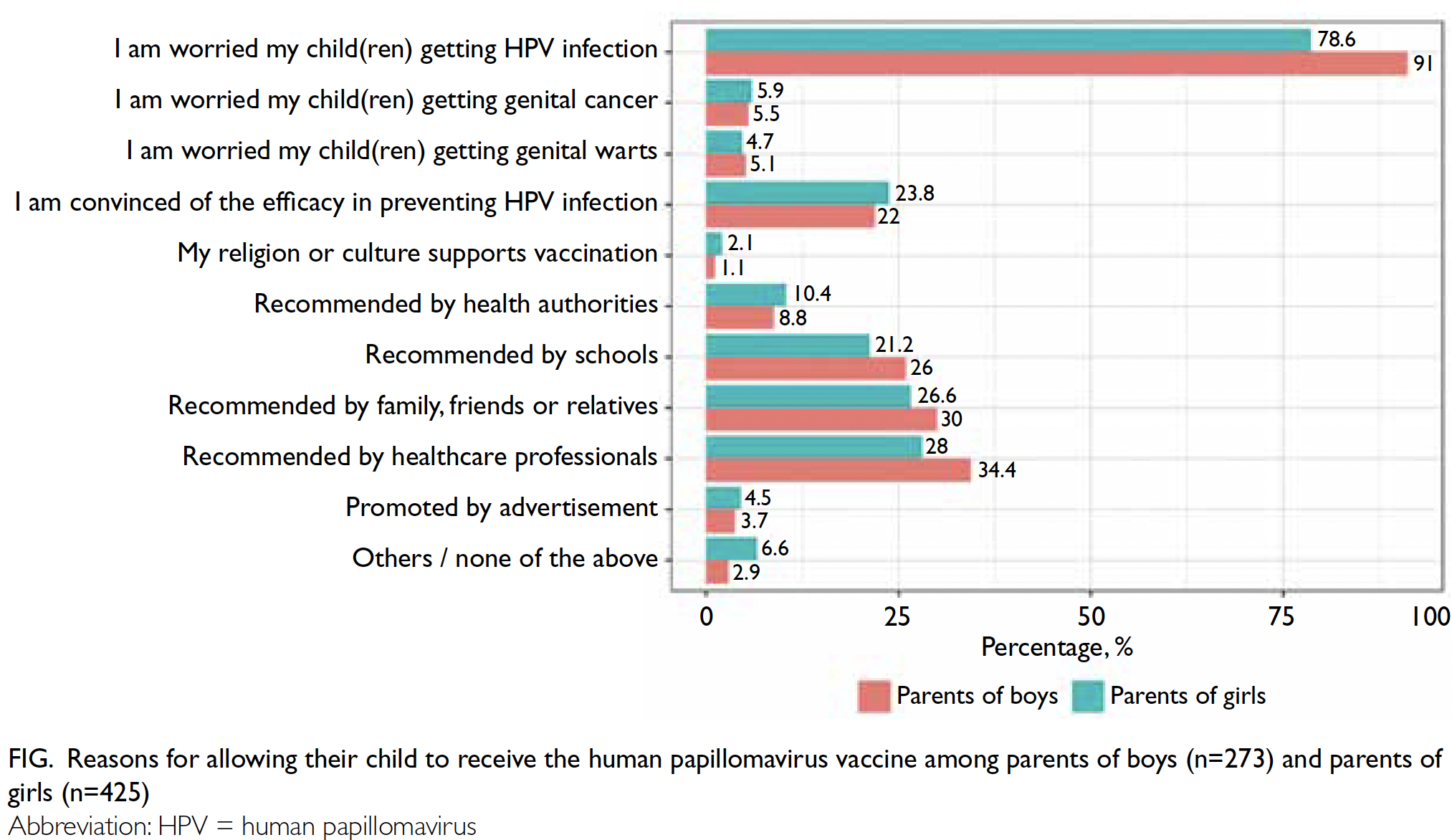

The reasons for accepting the HPV vaccine

for their children were similar between parent

groups (Fig), with a majority citing concerns about HPV infection (91.0% in boys’ parents and 78.6% in

girls’ parents). Acceptance was least influenced by

religions and culture (<3%) or advertisements (<5%)

in parents of both sexes. The reasons for declining

the HPV vaccine for their children were somewhat

different between boys’ parents and girls’ parents.

‘The HPV vaccine is too expensive’ was the top

reason chosen by both boys’ parents (46.4%) and

girls’ parents (42.9%). The other two reasons most

often selected by boys’ parents were ‘Not enough

information about the HPV vaccine provided to

me’ (32.0%) and ‘My child doesn’t like vaccinations’

(22.7%). For girls’ parents, the other two reasons

were ‘My child doesn’t like vaccinations’ (38.8%) and

‘The HPV vaccine can cause adverse effects/is not

safe’ (36.2%) [online supplementary Fig].

Figure. Reasons for allowing their child to receive the human papillomavirus vaccine among parents of boys (n=273) and parents of girls (n=425)

Factors associated with vaccine acceptance

for children

The association analysis excluded 25 parents of boys

and 23 parents of girls whose children had already

received the HPV vaccine. The acceptance rates

of the HPV vaccine for children of boys’ parents

and girls’ parents, stratified according to the study

variables, are listed in online supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

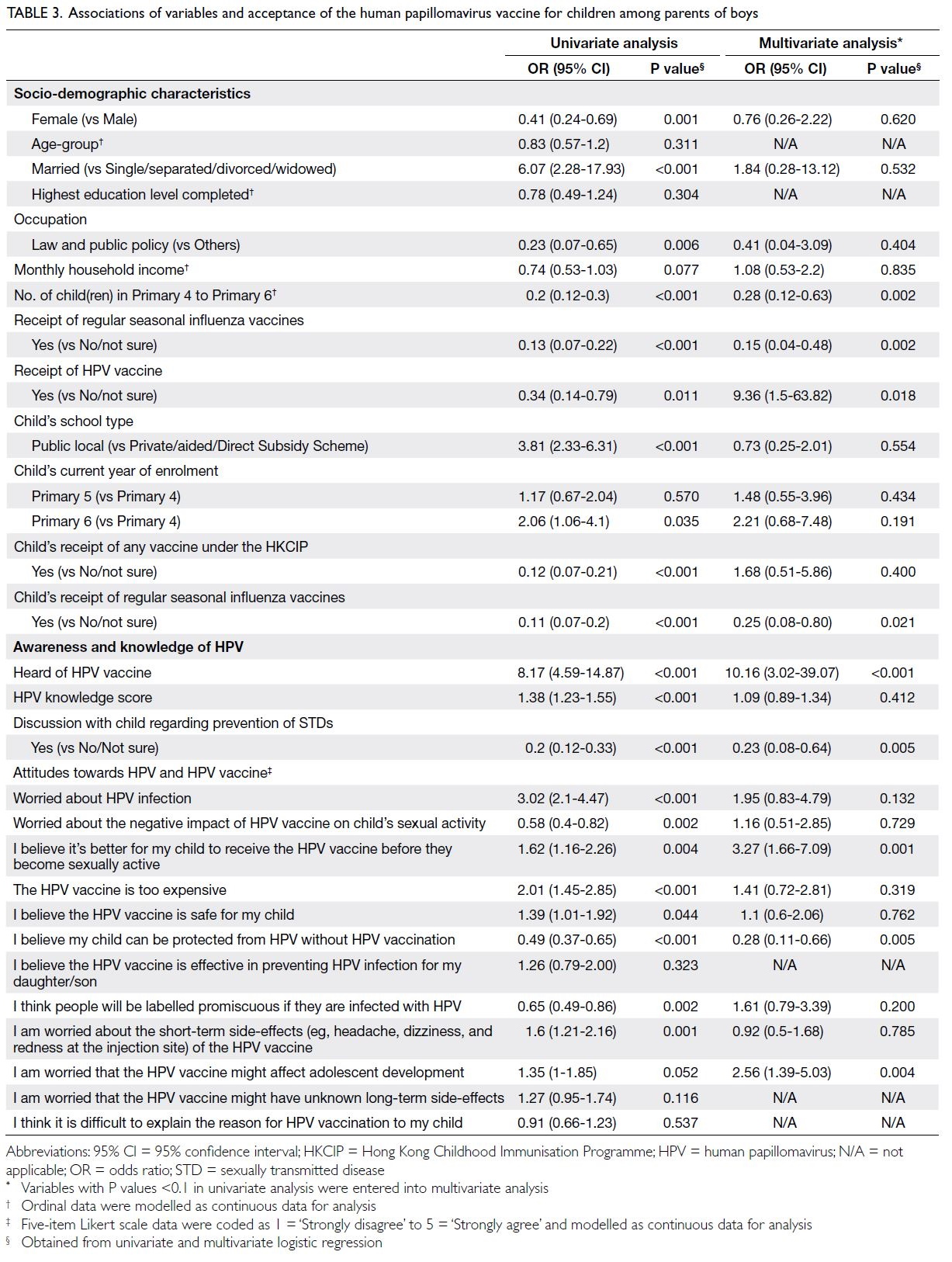

Regarding boys’ parents, 24 study variables with

P values <0.1 in univariate logistic regression were

entered into multivariate logistic regression (Table 3). Factors associated with higher acceptance of the HPV

vaccine for children included parental receipt of the

HPV vaccine (OR=9.36, 95% CI=1.5-63.82; P=0.018),

knowledge of the HPV vaccine (OR=10.16, 95%

CI=3.02-39.07; P<0.001), and stronger beliefs that

‘it’s better for my child to receive the HPV vaccine

before they become sexually active’ (OR=3.27, 95%

CI=1.66-7.09; P=0.001) and ‘I am worried that the

HPV vaccine might affect adolescent development’

(OR=2.56, 95% CI=1.39-5.03; P=0.004). Conversely,

factors associated with lower acceptance of the

HPV vaccine were the presence (in the respondents’

families) of more children in Primary 4 to Primary

6 (OR=0.28, 95% CI=0.12-0.63; P=0.002), a history

of discussing STD prevention with their children

(OR=0.23, 95% CI=0.08-0.64; P=0.005), receipt of

regular seasonal influenza vaccines (OR=0.15, 95%

CI=0.04-0.48; P=0.002), child’s receipt of regular

seasonal influenza vaccines (OR=0.25, 95% CI=0.08-0.80; P=0.021), and stronger beliefs that ‘my child can

be protected from HPV without HPV vaccination’

(OR=0.28, 95% CI=0.11-0.66; P=0.005) [Table 3].

Table 3. Associations of variables and acceptance of the human papillomavirus vaccine for children among parents of boys

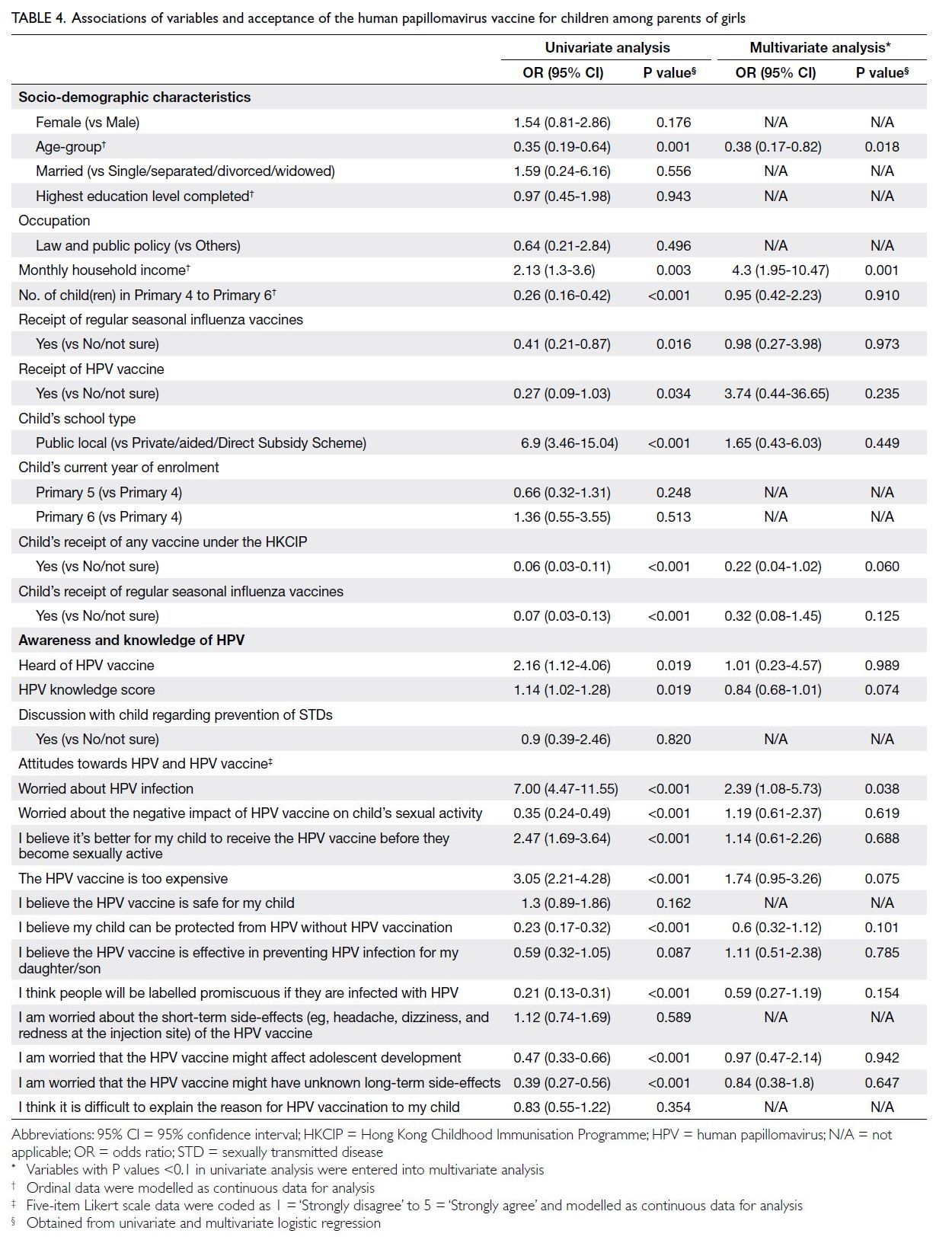

Regarding girls’ parents, 19 study variables were

entered into multivariate logistic regression. Higher

acceptance of the HPV vaccine for their children was

associated with higher monthly household income

(OR=4.3, 95% CI=1.95-10.47; P=0.001) and the

combined variable ‘worried about HPV infection’

(OR=2.39, 95% CI=1.08-5.73; P=0.038). Older age-group

(OR=0.38, 95% CI=0.17-0.82; P=0.018) was

the only variable associated with lower acceptance

of the HPV vaccine (Table 4).

Table 4. Associations of variables and acceptance of the human papillomavirus vaccine for children among parents of girls

Discussion

This survey of 844 Hong Kong parents (370 boys’

parents and 474 girls’ parents) revealed high HPV

vaccine awareness but relatively low knowledge of

HPV and the HPV vaccine. Parents believed the

vaccine was safe and effective in preventing HPV

infection. Acceptance of the HPV vaccine was lower

among boys’ parents than among girls’ parents,

and factors associated with acceptance differed

between the two parent groups. Differences in socio-demographic

characteristics were observed, such

that more boys’ parents discussed STDs with their

children and had experience with regular seasonal

influenza vaccines, the HPV vaccine, and Pap smears.

Understanding of human papillomavirus and the vaccine

Although a majority of parents of both sexes had

knowledge of the HPV vaccine, their average scores

indicated a low overall understanding of HPV and

HPV vaccination. This finding is consistent with

the results of previous studies, which showed that

general knowledge and awareness of HPV among

parents in Hong Kong remain low despite some

improvement over time.14 15 16 18 19 20 Considering the

substantial healthcare burden associated with HPV-related

diseases in Hong Kong, there is an urgent

need for educational or promotional programmes to

enhance vaccine acceptance and uptake.

In our study, parents expressed concern

about HPV infection and strongly favoured HPV

vaccination for their children before the children

became sexually active. These beliefs support

educational and promotional campaigns targeting

the early adolescent age-group.

The reported HPV vaccine uptake rate is low in

both groups (6.8% in boys and 4.9% in girls). The low

vaccine uptake rate reported in girls is particularly

alarming considering the recent inclusion of the

HPV vaccine in the HKCIP and the high vaccination

rate of 85% reported in the 2019/2020 school year.17

Among those parents who reported their children of

receiving the HPV vaccine, >90% of them, including

boys’ parents, indicated that their children received

the vaccine through the HKCIP. This finding

provides evidence suggesting insufficient public

health campaigns, resulting in a lack of knowledge

among parents on the HPV vaccination programme

and the HKCIP, subsequently leading to potential

confusion among parents.

Notably, girls’ parents in our study reported a

belief that the HPV vaccine is too expensive, despite

the availability of free HPV vaccination through the

HKCIP. This finding again reinforces a potential lack

of awareness regarding the Programme, possibly

due to inadequate dissemination of information

during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Similar trends have been observed in other

Western countries, where routine vaccinations

(including HPV vaccination) were disrupted by the

pandemic.21 22 Catch-up vaccination services for

affected children should be implemented promptly

to prevent future healthcare burdens.23 24 25 26

Concern for cost and vaccine safety

This study examined the factors influencing parental

acceptance of HPV vaccination for boys and girls.

Parents who had more children in Primary 4 to 6

were less likely to accept the vaccine, possibly due

to cost concerns. Discussions with children about

STD prevention and previous receipt of seasonal

flu vaccines did not lead to higher acceptance

rates. These findings imply that vaccination is not

a common topic in STD prevention campaigns, a

point that warrants attention in future educational

efforts focused on STD prevention. Intriguingly,

parents with greater concern that the HPV vaccine

affects adolescent development were more likely

to accept it; they also had higher knowledge and

awareness of HPV (online supplementary Table 3).

This result highlights the need to increase parental

understanding of HPV and the HPV vaccine,

including efforts to clarify potential misconceptions

and mitigate safety concerns.

Our data indicate that parental concerns

about HPV infection strongly influence vaccine

acceptance, whereas concerns about genital warts

and HPV-related cancers are less impactful. This

discrepancy may be attributed to an optimistic bias,

where parents associate HPV complications with

promiscuity and believe that their children have low

STD risk.18

Notably, parents ranked HPV vaccine

recommendations from healthcare professionals,

relatives and friends, and schools as more important

reasons to accept the vaccine, compared with

recommendations by health authorities. This result

may suggest that government initiatives provide

suboptimal education concerning HPV and the HPV

vaccine.

Barriers to HPV vaccine acceptance include

costs and children’s preferences, which may explain

the discrepancies between uptake and acceptance.

Cost is a well-established barrier to vaccination

uptake. However, we note that the vaccine is free

for girls in our study population, which highlights

the importance of awareness. Health messages to

boys’ parents should emphasise the value of HPV

vaccination as a long-term investment in their

sons’ health.14 Concerns about vaccine safety and

adverse effects, as well as a lack of recommendations

from healthcare professionals or a lack of general

knowledge, may also hinder vaccine acceptance.

We found that parental knowledge of HPV and

the HPV vaccine significantly influenced decision-making in boys’ parents, indicating that educational

campaigns targeting HPV acceptance may be more

effective for these parents than for girls’ parents. This

difference might be partly related to the feminisation

of HPV, especially in Hong Kong. This phenomenon

has been observed in a regional qualitative study

focusing on men’s perceptions of HPV and HPV

vaccination.27 Because the Chinese translation of the

HPV vaccine is ‘cervical cancer vaccine’, many boys

and men in Hong Kong perceive a low risk of HPV

infection.27 28 29 In this context, campaigns or strategies

using a fear-based approach to increase the perceived

risk of HPV infection may be more effective for boys’

parents.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, it was a

cross-sectional study and thus provided less robust

evidence than would be obtained in a longitudinal

study. Vaccine acceptance is merely an indicator

of potential uptake, and it is unclear whether this

acceptance will be translated into action. Second, this

study relied on parents to self-report their outcomes,

and it lacked the ability to verify information

provided by participants. Third, the results may have

been influenced by volunteer bias or other selection

biases. Because the survey was self-administered,

random sampling of the general study population

could not be achieved due to intrinsic differences

between those who did and did not choose to

participate. Volunteer bias may explain the variation

in baseline characteristics between boys’ parents and

girls’ parents. This bias limits the generalisability of

the study results to the broader population. Fourth,

the use of previously validated scales or items was

limited. Previous studies were used as a reference to

construct the survey questionnaire, but questions

were not directly adapted. Although such validated

measures exist, due to the lack of research regarding

HPV and HPV vaccination, no measures have been

validated in Hong Kong.30 31

One possible future research direction

involves conducting longitudinal studies to examine

the factors affecting vaccine uptake. These studies

can produce stronger evidence and more effectively

inform strategies for improved vaccine uptake.

Furthermore, because this study only screened for

variables involved in parental decision-making, a

more thorough investigation could be done to better

understand this process. Qualitative studies (eg,

involving focus groups or interviews) can provide a

more in-depth understanding of parents’ attitudes,

perceptions, and decision-making processes

regarding HPV vaccination acceptance.

Conclusion

This study represents the most extensive local

investigation into factors affecting parental acceptance of HPV vaccination in Hong Kong after

the implementation of a school-based outreach

programme. We found that high awareness of

HPV and the HPV vaccine is predictive of vaccine

acceptance. To increase vaccination rates among

adolescents, we recommend targeted interventions

based on the identified factors, including public

education for parents and children to raise awareness

of HPV risks, the benefits of vaccination for boys,

and STD prevention. We also suggest including HPV

vaccination for boys in the HKCIP and implementing

catch-up vaccination for affected children. Extension

of the catch-up programme to school children

beyond Primary 6 should be considered to maintain

high vaccination rates.

Author contributions

All authors (except for PH Wong and EYT So) contributed to

the concept or design of the study, acquisition of the data,

analysis or interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript,

and critical revision of the manuscript for important

intellectual content. PH Wong and EYT So contributed to the

concept and design of the study questionnaire. All authors

had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved

the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its

accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

PH Wong and EYT So are employees of Merck Sharp and

Dohme (Asia) Ltd. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts

of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr Ka-yu Tse from the Division of

Gynaecology Oncology of the Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology of The University of Hong Kong for review of

survey questions.

Funding/support

This research was sponsored by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC,

a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Inc (Rahway [NJ], United States)

[Ref No.: NIS009837]. The sponsor had no role in collection,

analysis, or interpretation of the data, nor did it participate in

manuscript preparation.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of

The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong

West Cluster, Hong Kong (Ref No.: UW21-574). Participants

provided informed consent via the online survey platform

before survey completion.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and

some information may not have been peer reviewed. Accepted

supplementary material will be published as submitted by the

authors, without any editing or formatting. Any opinions

or recommendations discussed are solely those of the

author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association. The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong

Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility

arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. de Martel C, Plummer M, Vignat J, Franceschi S. Worldwide

burden of cancer attributable to HPV by site, country and

HPV type. Int J Cancer 2017;141:664-70. Crossref

2. Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital Authority, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Cervical Cancer in 2017. October

2019. Available from: https://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/pdf/factsheet/2017/cx_2017.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb 2022.

3. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Cervical Cancer. 2024 January 12.

Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/healthtopics/content/25/56.html. Accessed 9 Sep 2024.

4. Lin C, Lau JT, Ho KM, Lau MC, Tsui HY, Lo KK. Incidence

of genital warts among the Hong Kong general adult

population. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10,272. Crossref

5. Garland SM, Kjaer SK, Muñoz N, et al. Impact and

effectiveness of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus

vaccine: a systematic review of 10 years of real-world

experience. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:519-27. Crossref

6. World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus

vaccines: WHO position paper, May

2017-Recommendations. Vaccine 2017;35:5753-5. Crossref

7. Markowitz LE, Hariri S, Lin C, et al. Reduction in human

papillomavirus (HPV) prevalence among young women

following HPV vaccine introduction in the United States,

National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 2003-2010. J Infect Dis 2013;208:385-93. Crossref

8. Elfström KM, Lazzarato F, Franceschi S, Dillner J, Baussano I.

Human papillomavirus vaccination of boys and extended

catch-up vaccination: effects on the resilience of programs.

J Infect Dis 2016;213:199-205. Crossref

9. Lehtinen M, Gray P, Louvanto K, Vänskä S. In 30 years,

gender-neutral vaccination eradicates oncogenic human

papillomavirus (HPV) types while screening eliminates

HPV-associated cancers. Expert Rev Vaccines 2022;21:735-8.Crossref

10. Division of Cancer Epidemiology & Genetics, National

Cancer Institute. HPV vaccine may provide men with herd

immunity against oral HPV infections. 2019 October 10.

Available from:

https://dceg.cancer.gov/news-events/news/2019/hpv-vaccine-herd-immunity. Accessed 10 Feb 2022.

11. Kahn JA, Brown DR, Ding L, et al. Vaccine-type human

papillomavirus and evidence of herd protection after

vaccine introduction. Pediatrics 2012;130:e249-56. Crossref

12. Merriel SW, Nadarzynski T, Kesten JM, Flannagan C,

Prue G. ‘Jabs for the boys’: time to deliver on HPV

vaccination recommendations. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:406-7. Crossref

13. Brisson M, Bénard É, Drolet M, et al. Population-level

impact, herd immunity, and elimination after human

papillomavirus vaccination: a systematic review and

meta-analysis of predictions from transmission-dynamic

models. Lancet Public Health 2016;1:e8-17. Crossref

14. Wang Z, Wang J, Fang Y, et al. Parental acceptability of HPV

vaccination for boys and girls aged 9-13 years in China—a

population-based study. Vaccine 2018;36:2657-65. Crossref

15. Li SL, Lau YL, Lam TH, Yip PS, Fan SY, Ip P. HPV

vaccination in Hong Kong: uptake and reasons for non-vaccination

amongst Chinese adolescent girls. Vaccine

2013;31:5785-8. Crossref

16. Choi HC, Leung GM, Woo PP, Jit M, Wu JT. Acceptability

and uptake of female adolescent HPV vaccination in

Hong Kong: a survey of mothers and adolescents. Vaccine

2013;32:78-84. Crossref

17. Hong Kong SAR Government. LCQ10: human

papillomavirus vaccination programme. 2021 January

20. Available from: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202101/20/P2021012000507.htm. Accessed 13 Feb 2022.

18. Wang LD, Lam WW, Fielding R. Determinants of human

papillomavirus vaccination uptake among adolescent girls:

a theory-based longitudinal study among Hong Kong

Chinese parents. Prev Med 2017;102:24-30. Crossref

19. Jones CL, Jensen JD, Scherr CL, Brown NR, Christy K,

Weaver J. The Health Belief Model as an explanatory

framework in communication research: exploring

parallel, serial, and moderated mediation. Health Comm

2015;30:566-76. Crossref

20. Chen JM, Leung DY. Factors associated with human

papillomavirus vaccination among Chinese female

university students in Hong Kong. Am Int J Soc Sci

2014;3:56-62.

21. Silva TM, Nogueira de Sá AC, Beinner MA, et al. Impact

of the COVID-19 pandemic on human papillomavirus

vaccination in Brazil. Int J Public Health 2022;67:1604224. Crossref

22. Damgacioglu H, Sonawane K, Chhatwal J, et al. Long-term

impact of HPV vaccination and COVID-19 pandemic on

oropharyngeal cancer incidence and burden among men

in the USA: a modeling study. Lancet Reg Health Am

2022;8:100143. Crossref

23. Shet A, Carr K, Danovaro-Holliday MC, et al. Impact of the

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on routine immunisation services:

evidence of disruption and recovery from 170 countries

and territories. Lancet Glob Health 2022;10:e186-94. Crossref

24. Ryan G, Gilbert PA, Ashida S, Charlton ME, Scherer A,

Askelson NM. Challenges to adolescent HPV vaccination

and implementation of evidence-based interventions to

promote vaccine uptake during the COVID-19 pandemic:

“HPV is probably not at the top of our list”. Prev Chronic

Dis 2022;19:E15. Crossref

25. Ogilvie GS, Remple VP, Marra F, et al. Intention of

parents to have male children vaccinated with the human

papillomavirus vaccine. Sex Transm Infect 2008;84:318-23. Crossref

26. Karafillakis E, Simas C, Jarrett C, et al. HPV vaccination in

a context of public mistrust and uncertainty: a systematic

literature review of determinants of HPV vaccine hesitancy

in Europe. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2019;15:1615-27. Crossref

27. Siu JY, Fung TK, Leung LH. Barriers to receiving HPV

vaccination among men in a Chinese community: a

qualitative study in Hong Kong. Am J Mens Health

2019;13:1557988319831912. Crossref

28. Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N,

Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination

among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature.

JAMA Pediatr 2014;168:76-82. Crossref

29. Trim K, Nagji N, Elit L, Roy K. Parental knowledge,

attitudes, and behaviours towards human papillomavirus

vaccination for their children: a systematic review from

2001 to 2011. Obstet Gynecol Int 2012;2012:921236. Crossref

30. Waller J, Ostini R, Marlow LA, McCaffery K, Zimet G.

Validation of a measure of knowledge about human

papillomavirus (HPV) using item response theory and

classical test theory. Prev Med 2013;56:35-40. Crossref

31. Perez S, Tatar O, Ostini R, et al. Extending and validating

a human papillomavirus (HPV) knowledge measure in a

national sample of Canadian parents of boys. Prev Med

2016;91:43-9. Crossref