Hong Kong Med J 2024 Oct;30(5):362–70 | Epub 3 Oct 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Mental health among parents and their children

with eczema in Hong Kong

PH Lam, MSSc, GMBPsS1; KL Hon, MB, BS, MD1,2; Steven Loo, MB, ChB, FRCP2; CK Li, MB, BS, MD1,3; Patrick Ip, MB, BS, FRCPCH4; Mark J Koh, MB, BS, MRCPCH5; Celia HY Chan, PhD, RSW6

1 Department of Paediatrics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Hong Kong Institute of Integrative Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Hong Kong Hub of Paediatric Excellence, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Dermatology Service, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, SingHealth Group, Singapore

6 Department of Social Work, Melbourne School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Australia

Corresponding author: Dr KL Hon (ehon@hotmail.com)

Abstract

Introduction: This cross-sectional survey research

investigated mental health symptoms and quality of

life among Chinese parents and their children with

eczema at a paediatric dermatology clinic in Hong

Kong from November 2018 to October 2020.

Methods: Health-related quality of life, eczema

severity, and mental health among children with

eczema, as well as their parents’ mental health,

were studied using the Children’s Dermatology Life

Quality Index (CDLQI), Infants’ Dermatitis Quality

of Life Index (IDQOL), Nottingham Eczema Severity

Score (NESS), Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure

(POEM), and the Chinese version of the 21-item

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (DASS-21).

Results: In total, 432 children and 380 parents

were recruited. Eczema severity (NESS and POEM)

and health-related quality of life (CDLQI) were

significantly positively associated with parental and

child depression, anxiety, and stress levels according

to the DASS-21, regardless of sex (children: r=0.28-

0.72, P<0.001 to 0.007; parents: r=0.20-0.52, P<0.001

to 0.034). Maternal depression was marginally

positively associated with increased anxiety in boys

with eczema (r=0.311; P=0.045). Younger parents

had higher risk of developing more anxiety and

stress compared with the older parents (adjusted

odds ratio [aOR]=-0.342, P=0.014 and aOR=-0.395,

P=0.019, respectively). Depression level of parents

with primary to secondary education was 58%

higher than their counterparts with post-secondary

education or above (aOR=-1.579; P=0.007).

Conclusion: Depression, anxiety, and stress among

children with eczema and their parents were

associated with eczema severity and impaired quality

of life in those children. These findings regarding

impaired mental health in children with eczema and

their parents highlight the need to include mental

well-being and psychosocial outcomes in future

studies and clinical practice.

New knowledge added by this study

- Depression, anxiety, and stress among children with eczema and their parents were associated with eczema severity and impaired quality of life in those children.

- Higher parental education level and advanced parental age could be the protective factors in dealing with emotional distress among parents whose children had eczema.

- The findings regarding impaired mental health in children with eczema and their parents highlight the need to include mental well-being and psychosocial outcomes in future studies and clinical practice.

Introduction

Atopic eczema (AE) is a common childhood

skin disease associated with pruritus and sleep

disturbance.1 2 3 4 5 Childhood AE can substantially

influence quality of life (QOL) among affected

children and their parents. The extent of QOL

impairment is often correlated with eczema severity, skin dehydration, and staphylococcal

infection.6 Additionally, many affected children

and their parents develop depression, anxiety, and

stress symptoms.1 These mental health issues are

correlated with disease severity, impaired QOL,

and therapeutic non-compliance.1 7 8 A study using

the 42-item Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (DASS-42) found that depression, anxiety, and stress

symptoms were present in 21%, 33%, and 23% of Hong

Kong adolescent patients with AE, respectively.1

These psychological symptoms were significantly

correlated with poor QOL.1 A study of Japanese

children showed eczema severity was associated

with mental health.9 Furthermore, a retrospective,

cross-sectional population-based survey of

childhood eczema in the United States revealed

that increased eczema severity was associated with

a higher risk of mental disorders.10 School-aged

children with moderate and severe AE have a higher

risk of psychosocial problems that can influence

their quality of sleep and cognitive development.11

Emotion, attention, interpersonal relationships, and

conduct can also be affected by AE.10 12 Moreover,

parents are often unaware of potential psychosocial

health issues in their children with eczema.13 Most

affected children and their parents do not receive

appropriate psychological help and support; they

also exhibit low symptom recognition. The impacts

of childhood eczema on the parent-child dyad have not been extensively studied in terms of healthrelated

quality of life (HRQOL), eczema severity, or

mental health status.14

This study was performed to examine

associations between mental health issues and

disease severity in children or adolescents with AE

and their parents using the concise validated 21-item

Chinese version of DASS-42 (DASS-21).1 15 16 17

Methods

Study design and participant recruitment

This 2-year cross-sectional survey was conducted

between November 2018 and October 2020.

Participants with a diagnosis of AE and their parents

were recruited at the paediatric dermatology clinic

of a university-affiliated hospital in Hong Kong.

Eczema was clinically diagnosed in accordance with

the United Kingdom Working Party’s Diagnostic

Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis.18 Participants

and their parents received information about the

study including objectives, procedures, voluntary

participation, and right of withdrawal. Non-Chinese

participants and individuals aged <11 years who were

not accompanied by a parent during recruitment

were excluded from the study.

The questionnaires were self-administered

and supervised by research staff. Parents would help

complete the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality

Index (CDLQI), Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life

Index (IDQOL), Nottingham Eczema Severity Score

(NESS), and Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure

(POEM) for their younger children. The DASS-21

was individually administered to all parents and to

children aged >11 years.

Clinical assessment of eczema

The validated Chinese version of the three-item NESS,

completed by children aged >11 years or the parents

of children aged ≤11 years, was used to determine

eczema severity in participating children.19 20 The

presence of eczema and number of nights affected by

skin itchiness each week in the past 12 months were

rated from 1 to 5. A higher score indicated greater

eczema severity. Additionally, areas of skin with

eczematous lesions (eg, rash, lichenified skin, and/or

bleeding) were recorded. Scores on the NESS were

categorised as mild (3 to 8), moderate (9 to 11), and

severe (12 to 15) eczema. Subjective measurements

were determined using the validated seven-item

Chinese translation of the POEM, which was also

completed by children aged >11 years or the parents

of children aged ≤11 years.21 22 Each item was scored

from 0 to 4, with a maximum aggregate score of 28.

A higher score indicated greater eczema severity in

the past week (ranges of 0-2, 3-7, 8-16, 17-24, and

25-28 correspond to clear, mild, moderate, severe,

and very severe levels of eczema, respectively).

Assessment of health-related quality of life

Health-related QOL was evaluated using the

Chinese version of the 10-item CDLQI23 and the

10-item IDQOL.24 The CDLQI was completed by

children aged ≥4 years with guidance from parents,

whereas the IDQOL was completed by parents of

children aged <4 years. Each item on the two scales

was scored from 0 to 3, with a maximum aggregate

score of 30. A higher score indicated greater eczema-related

HRQOL impairment in the past week

(CDLQI ranges of 0-1, 2-6, 7-12, 13-18, and 19-30

correspond to no, small, moderate, very large, and

extremely large effects on HRQOL, respectively;

these ranges for IDQOL are 0-1, 2-5, 6-10, 11-20,

and 21-30, respectively).

Assessment of mental health

Mental health was assessed by measuring depression,

anxiety, and stress in children with eczema and

their parents using the validated Chinese version of

the DASS-21. This scale has been used to examine

symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress

among individuals with dermatitis or eczema.1 17

The DASS-21 was individually administered to

all parents and to children aged >11 years. The

DASS-21 composite score can be divided into the

DASS Depression, DASS Anxiety, and DASS Stress

domains. The total score for each domain ranges from

0 to 42.25 A higher score indicates greater emotional distress in that domain (DASS Depression ranges of 0-9, 10-13, 14-20, 21-27, and ≥28 correspond

to normal, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely

severe levels, respectively; these ranges for DASS

Anxiety are 0-7, 8-9, 10-14, 15-19, and ≥20, whereas

they are 0-14, 15-18, 19-25, 26-33, and ≥34 for DASS

Stress).

Statistical analysis

Clinical data were de-identified and analysed using

SPSS (Windows version 25.0; IBM Corp, Armonk

[NY], United States). Frequency distributions were

used to describe the demographic and clinical

characteristics of participants. Continuous variables

with normal distributions were expressed as means±standard deviations (corrected to 1 decimal place).

Nominal and ordinal variables were expressed in

numbers with percentage (corrected to 1 decimal

place). Independent samples t tests were used to

explore sex differences regarding age, education

level, disease severity, QOL, and emotional distress

in parents and children. Pearson correlation analysis

was utilised to examine associations among mental

health, eczema severity, and HRQOL in parents and

children of both sexes. Multiple linear regression

was performed to adjust for variations in parental

and child DASS scores and HRQOL according to

demographic and clinical variables. P values <0.05

were considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic information, disease state, and mental well-being among children and parents

Among 380 parents (mean age=41.13±6.52 years), 49 were fathers (mean age=42.50±7.49 years) and 331 were mothers (mean age=40.95±6.36 years).

Parents’ education levels were primary to secondary

(n=124, 13 males), post-secondary (n=26, 1 male),

and undergraduate or above (n=81, 14 males) [Table 1]. Parents reported moderate to extremely severe

depression (n=58, 2 males), moderate to extremely

severe anxiety (n=101, 5 males), and moderate to

extremely severe stress (n=90, 6 males). Parents

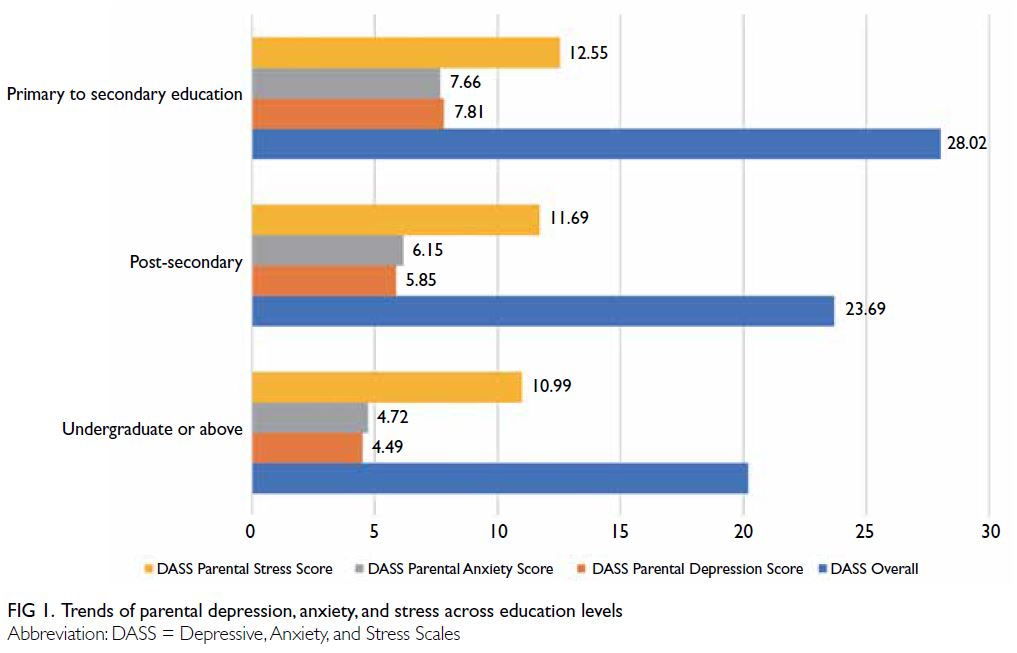

with a higher education level had lower levels of

depression, anxiety, and stress (Fig 1). Compared

with fathers, mothers generally had higher overall

DASS-21 depression, anxiety, and stress scores

(P<0.001-0.005) [Table 1].

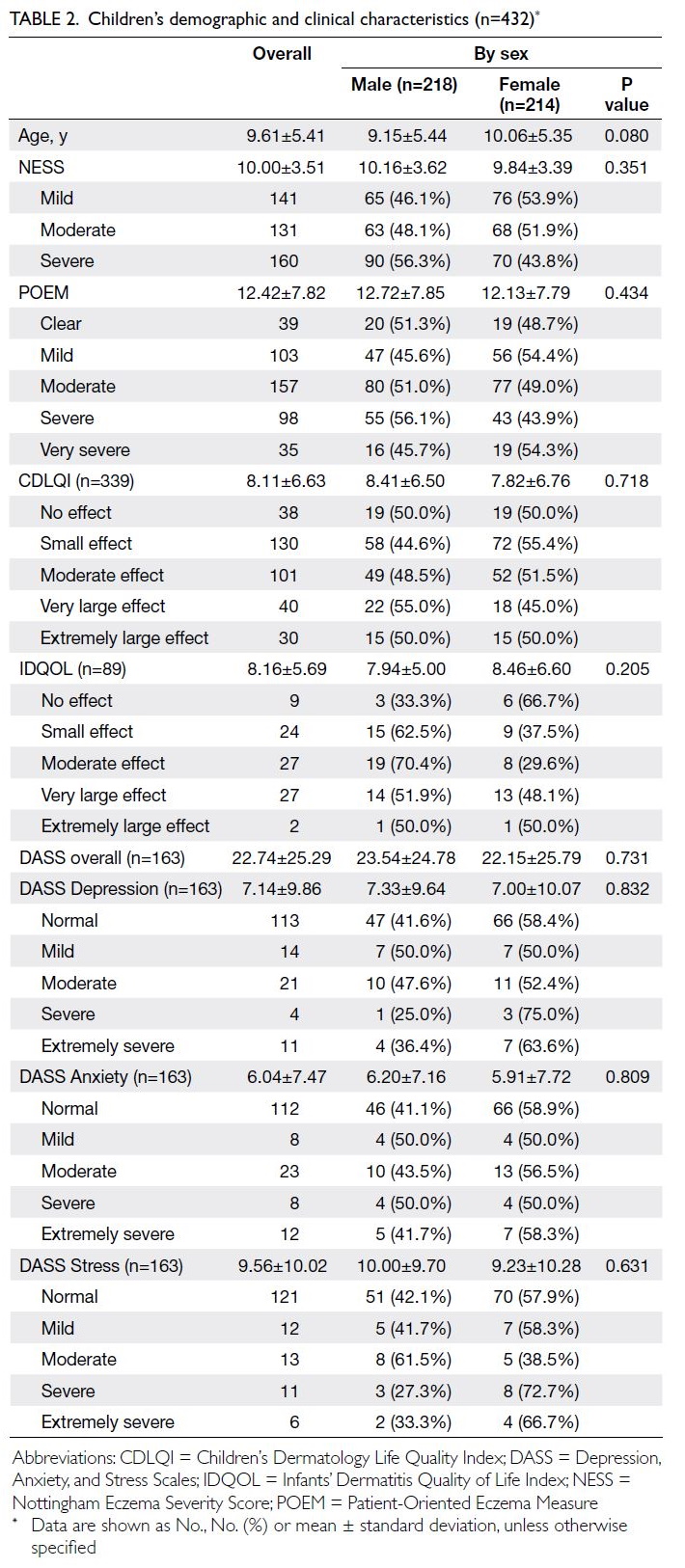

Among 432 children (mean age=9.61±5.41

years), 218 were boys (mean age=9.15±5.44 years)

and 214 were girls (mean age=10.06±5.35 years).

Most children had moderate to severe/very severe

disease according to the POEM (n=290) and NESS

(n=291). Over half of the children displayed a

moderate to extremely large impact on QOL in the

CDLQI (n=171, 50.4%) and IDQOL (n=56, 62.9%).

Small numbers of children had moderate to extremely

severe depression (n=36), anxiety (n=43), and stress

(n=30). There were no significant sex differences in

disease severity, HRQOL, or emotional distress in

the DASS (Table 2).

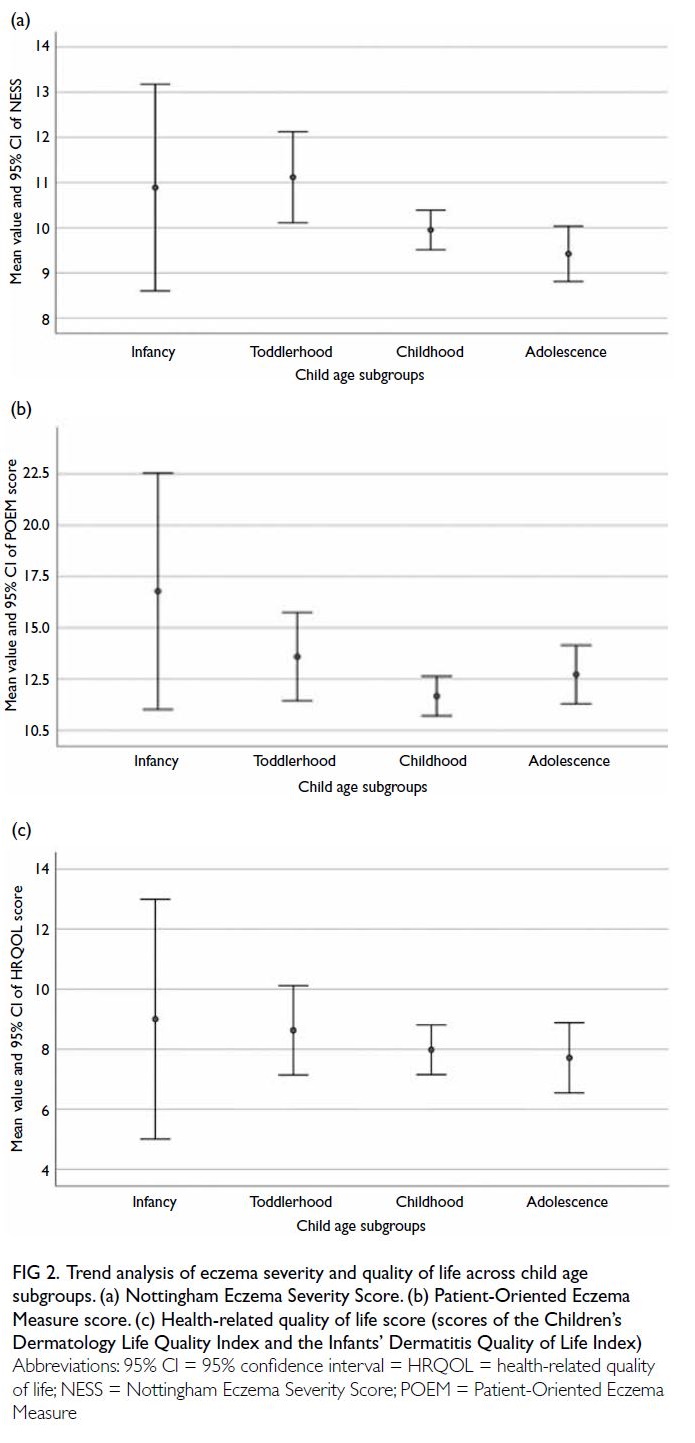

Eczema severity, health-related quality of life, and mental health among children

Disease severity in terms of NESS, POEM, and HRQOL (ie, CDLQI and IDQOL) was generally

worse among infants than among older children

(Fig 2). Thus, eczema severity and QOL generally

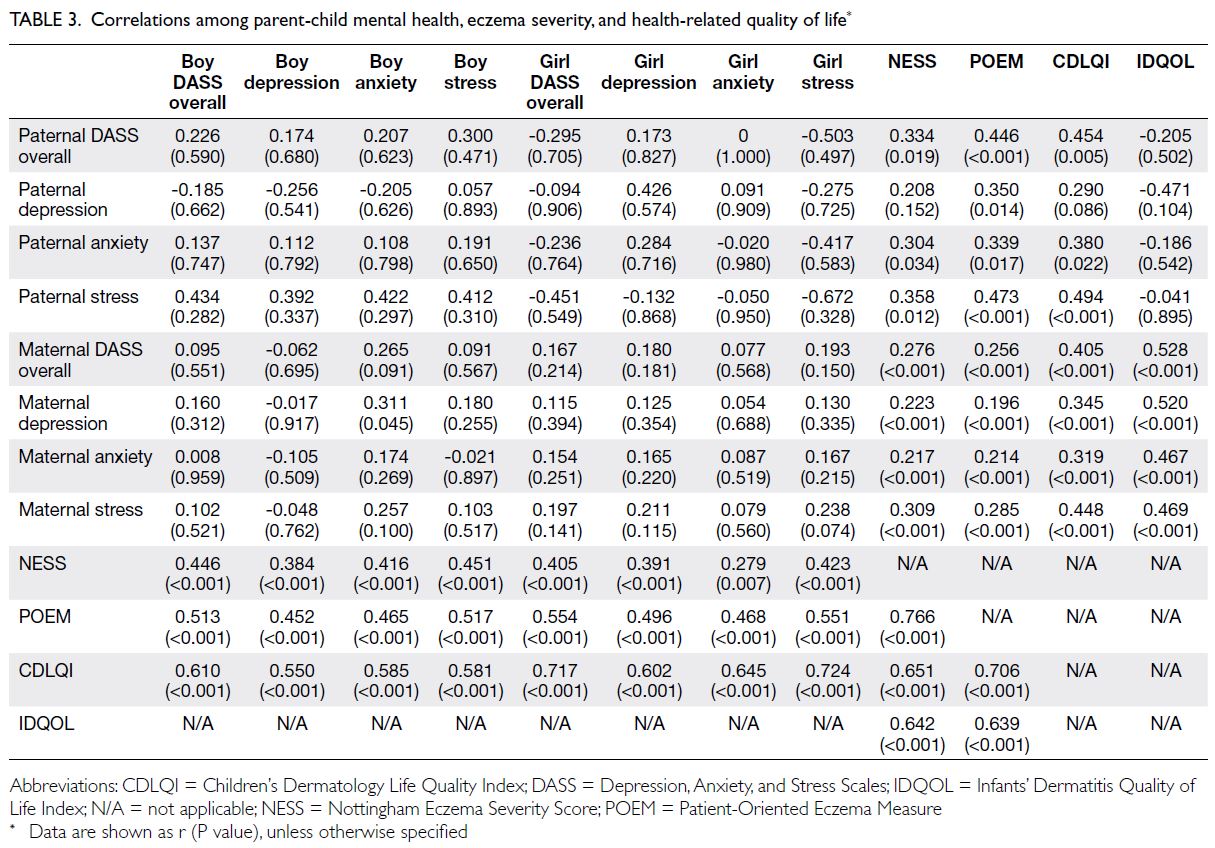

appeared to improve with age. Correlation analysis

demonstrated that depression, anxiety, and stress

levels were significantly associated with NESS,

POEM, and CDLQI, regardless of sex (Table 3).

Figure 2. Trend analysis of eczema severity and quality of life across child age subgroups. (a) Nottingham Eczema Severity Score. (b) Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure score. (c) Health-related quality of life score (scores of the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index and the Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index)

Table 3. Correlations among parent-child mental health, eczema severity, and health-related quality of life

Eczema severity, health-related quality of

life, and mental health among parents

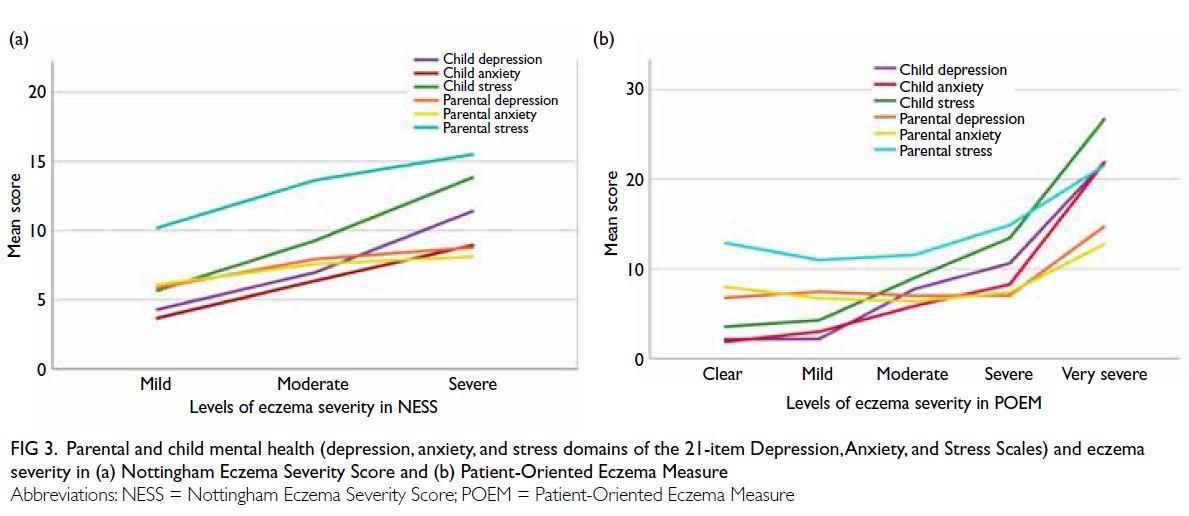

Correlation analysis revealed that eczema severity

(NESS and POEM) and HRQOL (CDLQI) were

associated with depression, anxiety, and stress levels

(DASS-21) among children and parents, regardless

of sex (Table 3 and Fig 3). Moreover, depression,

anxiety, and stress levels in mothers were significantly

correlated with NESS, POEM, IDQOL, and CDLQI.

Paternal anxiety and stress levels were correlated

with NESS, POEM, and CDLQI (P<0.001 to 0.034).

However, paternal depression was only correlated

with POEM (P=0.014) [Table 3].

Figure 3. Parental and child mental health (depression, anxiety, and stress domains of the 21-item Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales) and eczema severity in (a) Nottingham Eczema Severity Score and (b) Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure

Mental health among children and parents

Maternal depression showed a marginal association

with higher anxiety levels in boys with eczema (n=42,

r=0.311; P=0.045) [Table 3]. However, considering

the small number of pairs, no clinical or statistical inferences should be made regarding sex differences

in mental health among children and parents.

Additionally, there were no statistically significant

associations between the mental health of children

and parents concerning depression, anxiety, and

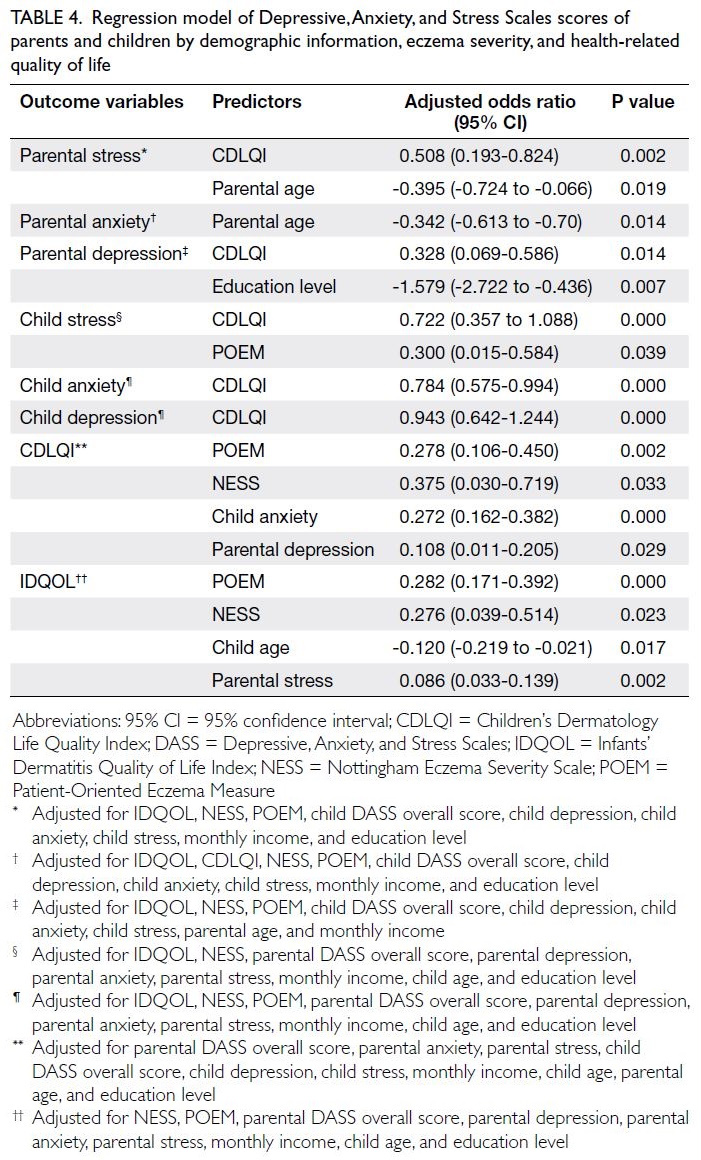

stress levels in the DASS-21 (Table 3). Regression

analysis showed that the child’s HRQOL and

parental age mostly explained variation in parental

anxiety and stress, whereas parental education level

explained variation in parental depression (Table 4). Younger parents had higher risk of developing

more anxiety and stress compared with the older

parents. Depression level of parents with primary

to secondary education was 58% higher than their

counterparts with post-secondary education or

above. Conversely, the child’s eczema severity and

HRQOL mostly explained the child’s emotional

distress. Eczema severity and parental emotional

distress significantly affected HRQOL in children of

all ages (Table 4).

Table 4. Regression model of Depressive, Anxiety, and Stress Scales scores of parents and children by demographic information, eczema severity, and health-related quality of life

There was no psychological or physiological discomfort resulted from administration of the surveys.

Discussion

Psychological symptoms of depression, anxiety, and

stress were prevalent among children with AE and

their parents. Our findings indicate associations

between the mental health of children and parents

and the eczema severity in those children. Increased

eczema severity in children and adolescents led to

greater emotional distress in parents and children,

regardless of sex. Similarly, psychological symptoms in

children and their parents were negatively correlated

with the child’s eczema severity (NESS and POEM)

and HRQOL impairment (CDLQI or IDQOL),

regardless of sex. These strong correlations suggest

that psychological symptoms, eczema severity, and

impact on QOL have mutually detrimental effects.

The DASS depression, anxiety, and stress scores were

generally higher among mothers than among fathers,

suggesting that mothers (the primary caregivers for

children with eczema) were more strongly affected.

The present study showed that eczema severity can

adversely affect emotions and QOL among parents

and children, highlighting the need for further

exploration of biopsychosocial interactions among

children and adolescents with eczema. Children with

severe disease reportedly have more problems with

depression and internalising behaviour.26 Behavioural

issues can lead to adverse social interactions with

peers, further reducing self-esteem and HRQOL.

Therefore, interactions among parental perception

of the child’s disease severity, the child’s treatment

adherence, the child’s social influence by peers, and

the child’s school environment should be considered

when clinicians make comprehensive decisions

about holistic treatments.

Our results using the DASS-21 are consistent

with findings in previous studies1 27 that used the more comprehensive DASS-42. As in previous

studies,1 27 we found that caregivers were especially

likely to experience anxiety related to care provision

in the home.28 29 In the present study, maternal

depression was associated with a higher anxiety

level, particularly in relation to boys with eczema.

Accordingly, the Harmonising Outcome Measures

for Eczema initiative recommends documentation

of disease severity and QOL impairment in

eczema cases.25 30 However, there have been few

international initiatives and clinical trials regarding

the psychological symptoms of caregivers and

patients, particularly in the context of childhood

eczema. Therefore, we suggest that clinicians should

consider these important measurable domains in

terms of therapeutic interventions and psychological

support. Childhood eczema treatments mainly focus

on pharmacological control of physical symptoms,

but they often completely neglect the psychological

symptoms of affected children and their parents.

A more holistic treatment approach is needed for

this potentially devastating common childhood

disorder. Given the increasing numbers of proposed

assessment tools, we advocate a holistic and

comprehensive approach for eczema management

that considers children and their families. This

treatment tool should use a composite score to

continuously evaluate disease severity (in objective

and subjective manners), QOL impairment,

psychological symptoms, and miscellaneous

disease surrogates in affected children and their

parents.1 16 21 26

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was that compared with

the DASS-42, the DASS-21 demonstrated better

performance with 50% fewer questions and a shorter

completion time. Findings from the DASS-21, but

not the DASS-42, were correlated with disease

severity as measured by the NESS and POEM.1

These discrepancies could have arisen because the

sample size in the present study (using the DASS-21) was threefold greater than the sample size in

the previous DASS-42 study.1 In the present study,

the DASS-21, especially in child and mother, was

moderately to strongly correlated with the CDLQI,

IDQOL, NESS, and POEM. Thus, the DASS-21 can

effectively represent the degree of emotional distress

among parents and children or adolescents with

eczema. This questionnaire is available in different

languages, potentially allowing it to be used for

assessment of patients with other ethnicities. To our

knowledge, this is the first study to use the DASS-21

to assess the mental health of parents and children

with eczema in a paediatric setting. This study revealed the presence of childhood eczema-related

depression, anxiety, and stress in affected children

and their parents.

This study had a few limitations including its

relatively small sample size, especially concerning

father-child pairs. A greater proportion of mothers

participated in this study, which is expected because

mothers are the main caregivers for children with

eczema; they typically accompany their children

during medical consultations. Considering that

paediatric dermatological clinics also cater adolescent patients aged ≥16 years, a few participants

aged 16 to 19 years completed the CDLQI on their

HRQOL; although these participants exceeded the

suggested age range of ≤16 years, the overall results

were not affected.

Another limitation is that the number of

recruited mothers, who are normally regarded

as the main child caregiver, much outweighs that

of recruited fathers. In addition, compared with

fathers, mothers may know their child’s health

more and get anxious or depressed as the eczema

severity of their child escalates over time. Thus, the

difference of the role in childbearing, sample size

and the understanding of child’s health may affect

the findings in parental-child correlations. It should

be cautious when the results regarding parental-child

correlations are studied and presented. The

CDLQI (n=339) is a questionnaire for children,

and the IDQOL (n=89) is for infants. The different

numbers of participants who completed each of

these questionnaires is consistent with the CDLQI

coverage of a broader age range, whereas the IDQOL

is only suitable for children aged <4 years. Although

maternal depression was correlated with boys

with anxiety, it is important to note that statistical

significance should not be used to infer that there

is a sex difference between parent and child groups

in terms of mental health; such an inference would

constitute overgeneralisation.

Conclusion

Children with eczema and their parents demonstrated

mental health impairment, which was correlated

with disease severity. Eczema-induced anxiety,

stress, and other mental health issues in affected

children and their parents should be considered

by healthcare professionals during comprehensive

assessments for the treatment of eczema. In addition

to primary eczema, possible secondary psychiatric

symptoms should be monitored in children with

moderate to severe eczema and their parents.

Childhood eczema severity and the mental health

of affected children and their parents should be

simultaneously evaluated to prevent and manage

secondary psychological problems.

Author contributions

Concept or design: KL Hon.

Acquisition of data: PH Lam.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PH Lam, P Ip.

Drafting of the manuscript: PH Lam, KL Hon.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KL Hon, S Loo, MJ Koh, CHY Chan, CK Li, P Ip.

Acquisition of data: PH Lam.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PH Lam, P Ip.

Drafting of the manuscript: PH Lam, KL Hon.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KL Hon, S Loo, MJ Koh, CHY Chan, CK Li, P Ip.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KL Hon was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all children and parents who participated in this research.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee, Hong Kong (Ref No.: CRE.2018.401).

Written informed consent was obtained from participants

and parents prior to the research.

References

1. Hon KL, Pong NH, Poon TC, et al. Quality of life and

psychosocial issues are important outcome measures in

eczema treatment. J Dermatolog Treat 2015;26:83-9. Crossref

2. Leung AK, Hon KL, Robson WL. Atopic dermatitis. Adv Pediatr 2007;54:241-73. Crossref

3. Leung TN, Hon KL. Eczema therapeutics in children: what do the clinical trials say? Hong Kong Med J 2015;21:251-60. Crossref

4. Hon KL, Lam PH, Ng WG, et al. Age, sex, and disease status

as determinants of skin hydration and transepidermal

water loss among children with and without eczema. Hong

Kong Med J 2020;26:19-26. Crossref

5. Hon KL, Wong KY, Leung TF, Chow CM, Ng PC.

Comparison of skin hydration evaluation sites and

correlations among skin hydration, transepidermal water

loss, SCORAD index, Nottingham Eczema Severity Score,

and quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J

Clin Dermatol 2008;9:45-50. Crossref

6. Holm EA, Wulf HC, Stegmann H, Jemec GB. Life quality

assessment among patients with atopic eczema. Br J

Dermatol 2006;154:719-25. Crossref

7. Slattery MJ, Essex MJ, Paletz EM, et al. Depression, anxiety,

and dermatologic quality of life in adolescents with atopic

dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:668-71. Crossref

8. Magin PJ, Pond CD, Smith WT, Watson AB, Goode SM.

Correlation and agreement of self-assessed and objective

skin disease severity in a cross-sectional study of patients

with acne, psoriasis, and atopic eczema. Int J Dermatol

2011;50:1486-90. Crossref

9. Kuniyoshi Y, Kikuya M, Miyashita M, et al. Severity

of eczema and mental health problems in Japanese

schoolchildren: the ToMMo Child Health Study. Allergol

Int 2018;67:481-6. Crossref

10. Wan J, Takeshita J, Shin DB, Gelfand JM. Mental health

impairment among children with atopic dermatitis: a

United States population-based cross-sectional study of

the 2013-2017 National Health Interview Survey. J Am

Acad Dermatol 2020;82:1368-75. Crossref

11. Fishbein AB, Cheng BT, Tilley CC, et al. Sleep disturbance

in school-aged children with atopic dermatitis: prevalence

and severity in a cross-sectional sample. J Allergy Clin

Immunol Pract 2021;9:3120-9.e3. Crossref

12. Schmitt J, Apfelbacher C, Chen CM, et al. Infant-onset

eczema in relation to mental health problems at age

10 years: results from a prospective birth cohort study

(German Infant Nutrition Intervention plus). J Allergy Clin

Immunol 2010;125:404-10. Crossref

13. Walker C, Papadopoulos L, Hussein M. Paediatric eczema

and psychosocial morbidity: how does eczema interact

with parents’ illness beliefs? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol

2007;21:63-7. Crossref

14. Ali F, Vyas J, Finlay AY. Counting the burden: atopic

dermatitis and health-related quality of life. Acta Derm

Venereol 2020;100:adv00161. Crossref

15. Wong KC. Psychometric investigation into the construct

of neurasthenia and its related conditions: a comparative

study on Chinese in Hong Kong and Mainland China

[dissertation]. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong

Kong; 2009.

16. Lam PH, Hon KL, Leung KK, Leong KF, Li CK, Leung TF.

Self-perceived disease control in childhood eczema. J

Dermatolog Treat 2022;33:1459-64. Crossref

17. Gong X, Xie XY, Xu R, Luo YJ. Psychometric properties

of the Chinese versions of DASS-21 in Chinese college

students [in Chinese]. Chinese J Clin Psychol 2010;18:443-6.

18. Williams HC, Burney PG, Pembroke AC, Hay RJ. The U.K.

Working Party’s Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis.

III. Independent hospital validation. Br J Dermatol

1994;131:406-16. Crossref

19. Emerson RM, Charman CR, Williams HC. The Nottingham

Eczema Severity Score: preliminary refinement of the Rajka

and Langeland grading. Br J Dermatol 2000;142:288-97. Crossref

20. Hon KL, Ma KC, Wong E, Leung TF, Wong Y, Fok TF.

Validation of a self-administered questionnaire in Chinese

in the assessment of eczema severity. Pediatr Dermatol

2003;20:465-9. Crossref

21. Hon KL, Kung JS, Tsang KY, Yu JW, Cheng NS, Leung TF.

Do we need another symptom score for childhood eczema?

J Dermatolog Treat 2018;29:510-4. Crossref

22. Gaunt DM, Metcalfe C, Ridd M. The Patient-Oriented

Eczema Measure in young children: responsiveness

and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy

2016;71:1620-5. Crossref

23. Salek MS, Jung S, Brincat-Ruffini LA, et al. Clinical

experience and psychometric properties of the Children’s

Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI), 1995-2012. Br J

Dermatol 2013;169:734-59. Crossref

24. Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY, Dykes PJ. The Infants’

Dermatitis Quality of Life Index. Br J Dermatol

2001;144:104-10. Crossref

25. Gerbens LA, Prinsen CA, Chalmers JR, et al. Evaluation

of the measurement properties of symptom measurement

instruments for atopic eczema: a systematic review. Allergy

2017;72:146-63. Crossref

26. Hon KL, Kam WY, Lam MC, Leung TF, Ng PC. CDLQI,

SCORAD and NESS: are they correlated? Qual Life Res

2006;15:1551-8. Crossref

27. Duran S, Atar E. Determination of depression, anxiety and

stress (DAS) levels in patients with atopic dermatitis: a

case-control study. Psychol Health Med 2020;25:1153-63. Crossref

28. Shelley AJ, McDonald KA, McEvoy A, et al. Usability,

satisfaction, and usefulness of an illustrated eczema action

plan. J Cutan Med Surg 2018;22:577-82. Crossref

29. Rork JF, Sheehan WJ, Gaffin JM, et al. Parental response to

written eczema action plans in children with eczema. Arch

Dermatol 2012;148:391-2. Crossref

30. Spuls PI, Gerbens LA, Simpson E, et al. Patient-Oriented

Eczema Measure (POEM), a core instrument to measure

symptoms in clinical trials: a Harmonising Outcome

Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement. Br J Dermatol

2017;176:979-84. Crossref