Hong Kong Med J 2024 Oct;30(5):355–61 | Epub 10 Oct 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity after normal therapeutic doses in the Hong Kong Chinese population

WH Tsang, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)1; CK Chan, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine), FHKCEM (Clinical Toxicology)2; ML Tse, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine), FHKCEM (Clinical Toxicology)2

1 Accident and Emergency Department, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Hong Kong Poison Information Centre, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr WH Tsang (tsanwh1@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Paracetamol is generally safe at

normal therapeutic doses of ≤4 g/day in adults.

However, paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity after

normal therapeutic doses use has been reported. We

investigated the epidemiology of this adverse drug

reaction in the Hong Kong Chinese population.

Methods: This territory-wide retrospective

observational study included adult patients with

suspected paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity

after normal therapeutic doses use from January

2011 to June 2022. We evaluated the demographic

characteristics; paracetamol dose, duration, and

reason for use; preexisting hepatotoxicity risk

factors; laboratory findings; and their relationship

with clinical outcomes.

Results: We identified 76 patients (median age:

74 years, 23 males) with suspected paracetamol-induced

hepatotoxicity after normal therapeutic

doses use. There were 14 cases with significant

clinical outcomes (five deaths and nine cases of acute

hepatic failure), with an incidence of 1.2 cases per

year. For patients with significant clinical outcomes,

they were significantly older (age >80 years), had

a lower body weight (<50 kg), exposed to longer

durations (>2 days) and higher daily doses (>3 g), and with higher proportion of malnutrition.

Conclusion: Paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity

can occur at normal therapeutic doses in the Hong

Kong Chinese population. The identified risk factors

are consistent with international guidelines regarding

susceptible patients. Considering the widespread

local use of paracetamol and low incidence of severe

hepatotoxicity, the current dosage recommendations

are considered safe for the general population. For

susceptible patients, a reduced maximum dose of

≤3 g/day is recommended, with liver function and

serum paracetamol monitoring in place.

New knowledge added by this study

- Paracetamol can induce hepatotoxicity at normal therapeutic doses in high-risk groups.

- Dosage reduction to ≤3 g/day may reduce the incidence of serious liver injury.

- Physicians should consider a maximum dosage reduction from 4 g/day to 3 g/day in high-risk groups.

- High-risk groups included older age, lower body weight, malnutrition, exposure to longer duration of drug use, and higher daily dose.

Introduction

Paracetamol is a non-opioid analgesic recommended

as a first-line treatment for mild to moderate pain

and fever.1 It is one of the most widely used over-the-counter medications worldwide. In Hong

Kong, >600 registered pharmaceuticals contain

paracetamol.2 Adverse drug reactions in healthy

individuals are rare within the therapeutic dose

range. According to the British National Formulary,

the recommended daily dose of paracetamol is

4 g/day in divided doses for adults with body

weight ≥50 kg.3 Special precautions are needed for individuals with a high risk of hepatotoxicity,

including those with body weight <50 kg,

chronic alcoholism, chronic dehydration, chronic

malnutrition, hepatocellular insufficiency, and/or

concomitant use of P450 liver enzyme inducers

(eg, antituberculosis drugs, antiepileptic drugs, and

herbs/dietary supplements such as St John’s wort).

Paracetamol is metabolised through various

pathways in the liver. In healthy individuals taking

normal therapeutic doses, >90% of paracetamol

undergoes glucuronidation and sulphation, followed

by renal excretion.4 Only 5% to 10% is oxidised by cytochrome P450 to the toxic metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine, which is subsequently

neutralised by glutathione and undergoes renal

excretion. However, in cases of paracetamol overdose

or glutathione depletion, excessive production and

accumulation of N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine

in hepatocytes can result in acute liver injury.

N-acetylcysteine, the primary antidote in such

situations, acts by replenishing hepatic glutathione.5

Theoretically, paracetamol hepatotoxicity can occur

after normal therapeutic dose use in patients with

critically depleted glutathione levels.

There have been few reports of paracetamolinduced

hepatotoxicity after normal therapeutic

doses use.6 7 8 Most of these cases had at least one of

the aforementioned risk factors. In 2022, the United

Kingdom’s Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch

published a report recommending a prescription

alert for individuals with body weight <50 kg who

are prescribed paracetamol.9 The Queensland

Government’s Department of Health of Australia

also revised its paracetamol use guidelines,

recommending ≤3 g/day for adults with risk

factors such as advanced age or low body weight.10

When risk factors are present and treatment

continues beyond 48 hours, liver function test and

international normalised ratio (INR) monitoring is

recommended.10 The United States Food and Drug

Administration states that it is safe to consume

≤4 g of paracetamol within 24 hours,11 whereas the Irish Health Products Regulatory Authority

recommends ≤2 g of paracetamol for patients with

mild to moderate hepatic insufficiency or chronic

alcoholism.12

Isolated cases of paracetamol-induced

hepatotoxicity causing death or acute hepatic

failure after normal therapeutic doses use have been

reported to the Hong Kong Poison Information

Centre (HKPIC). However, no local reports have

been published concerning the incidence of this rare

adverse drug reaction in the Hong Kong population.

This study aimed to describe the epidemiology and

incidence of paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in

the Hong Kong Chinese population.

Methods

Study design

This territory-wide retrospective observational study

included adult patients with suspected paracetamol-induced

hepatotoxicity after normal therapeutic

doses use reported to the HKPIC from 1 January

2011 to 30 June 2022 (11.5 years in total).

Study setting and data sources

The HKPIC was the only poison control centre in

Hong Kong during the study period. This centre

provides round-the-clock phone consultations

regarding poisoning cases to local healthcare

professionals and receives voluntary reports of

poisoning from all public emergency departments.13 14

The HKPIC maintains an electronic database, the

Poison Information and Clinical Management

System (PICMS), that contains information about

all consultations and reports received. Clinical data

from consultations and reports are entered into

the PICMS by staff trained in clinical toxicology.14

The data source for this study consisted of data

retrieved from the PICMS. When PICMS data were

incomplete, supplementary data were retrieved

from the Hospital Authority’s electronic Patient

Record system, which contains all medical records

(ie, clinical data, laboratory results, and outcomes)

of patients treated in public hospitals in Hong Kong.

Study population

All cases of paracetamol poisoning recorded in the

PICMS during the study period were identified.

Exclusion criteria were applied to ensure the

inclusion of only adult patients with suspected

paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity after normal

therapeutic doses use. These exclusion criteria

were age <18 years, intentional self-harm with

paracetamol, daily paracetamol consumption >4 g,

unknown paracetamol dose, co-ingestion with other

hepatotoxic drugs, or hepatotoxicity unrelated to

paracetamol.

Data collection

For the included cases, the following data were

collected: demographic characteristics including

age, sex, and ethnicity; duration of paracetamol use,

daily paracetamol dose, and reasons for paracetamol

use; risk factors including history of preexisting

liver disease, chronic alcoholism, use of P450 liver

enzyme-inducing medications, and malnutrition;

poisoning data including peak serum paracetamol

concentration, peak alanine transaminase (ALT)

level, peak INR, and receipt of N-acetylcysteine; and

clinical outcomes including death, acute liver failure,

mildly deranged liver function, and minimal effect.

Definitions

The diagnosis of paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity

was established on the basis of compatible clinical

and biochemical features, excluding other causes

of deranged liver function (eg, acute viral hepatitis,

autoimmune causes, and other drug- or herb-induced

hepatitis). All cases were reviewed by at least one

clinical toxicologist working in the HKPIC. Clinical

outcomes were defined as follows: ‘death’ was defined

as poisoning-related death, as judged by a clinical

toxicologist, within 30 days after hospitalisation;

‘acute hepatic failure’ was defined as severe acute

liver injury with an ALT level >1000 IU/L, associated

with encephalopathy and impaired synthetic function

within 26 weeks15; ‘mildly deranged liver function’

was defined as a peak ALT level >2 times the upper

limit of normal, without encephalopathy or impaired

synthetic function; and ‘minimal effect’ was defined as

a peak ALT level <2 times the upper limit of normal,

along with normal mental status. ‘Significant clinical

outcome’ cases were those with a clinical outcome

of death or acute hepatic failure. Malnutrition was

defined as documented insufficient energy intake for

>1 week.16

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS software (Windows version 29.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United

States). Continuous data were expressed as medians

(interquartile ranges); the Mann-Whitney U test

was used to compare the death and acute hepatic

failure groups with the minimal effect group.

Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies

and percentages; they were compared using the Chi

squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. All

statistical tests were two-sided, and P values <0.05

were considered statistically significant. Due to the

small sample size and low incidence of significant

clinical outcomes, multivariable logistic regression

was not performed.

Results

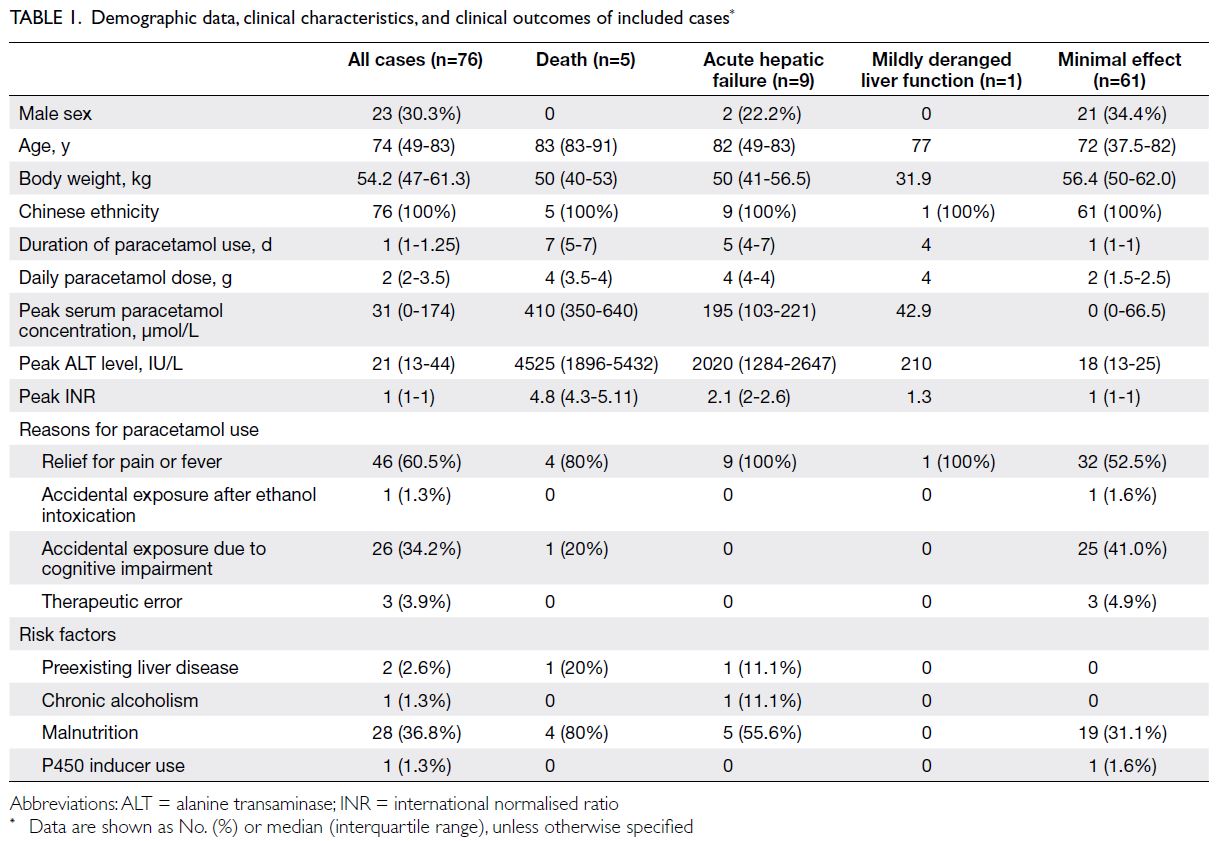

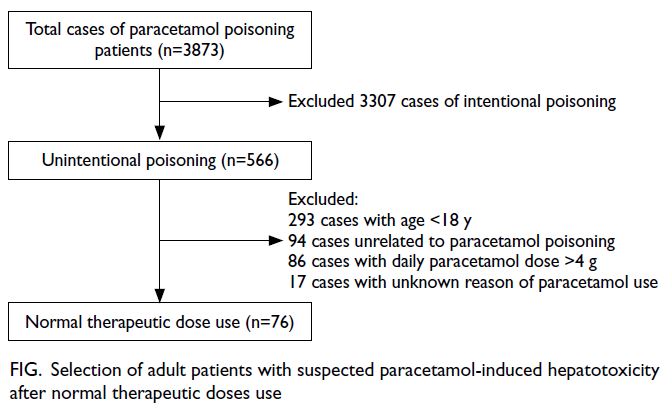

Within the study period, 3873 cases of paracetamol poisoning were identified. Reasons for exclusion

were intentional paracetamol poisoning, age <18

years, other causes of deranged liver function, daily

paracetamol dose >4 g, and unknown paracetamol

dose (Fig). In total, 76 patients were included in the

analysis; these patients were grouped according to

clinical outcomes. During the study period, five

patients died, nine patients developed acute hepatic

failure, one patient developed mildly deranged

liver function without coagulopathy or altered

mental status, and 61 patients showed minimal

effect; no patients underwent liver transplantation.

The incidence of significant clinical outcomes

(including death and acute hepatic failure) was 1.2

cases per year. Baseline demographic and clinical

characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Figure. Selection of adult patients with suspected paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity after normal therapeutic doses use

Most patients were women (69.7%). The

median age was 74 years and the median body weight

was 54.2 kg. All patients were of Chinese ethnicity.

Compared with the minimal effect group, patients

in the death group were older (median age: 83 vs 72

years; P=0.003), had a longer duration of paracetamol

use [median duration: 7 vs 1 day(s); P=0.001], and

had a higher daily paracetamol dose (median dose:

4 vs 2 g; P=0.004). Their body weights tended to

be lower, but this difference was not statistically

significant (median: 50 vs 56.4 kg; P=0.11). Moreover,

a higher percentage of patients in the death group

suffered from malnutrition (80% vs 31.1%; P=0.04),

and their peak serum paracetamol concentrations

were higher (median peak concentration: 410 vs

0 μmol/L; P<0.001), exceeding the normal range of

<130 μmol/L despite the use of normal therapeutic

doses (Table 1).

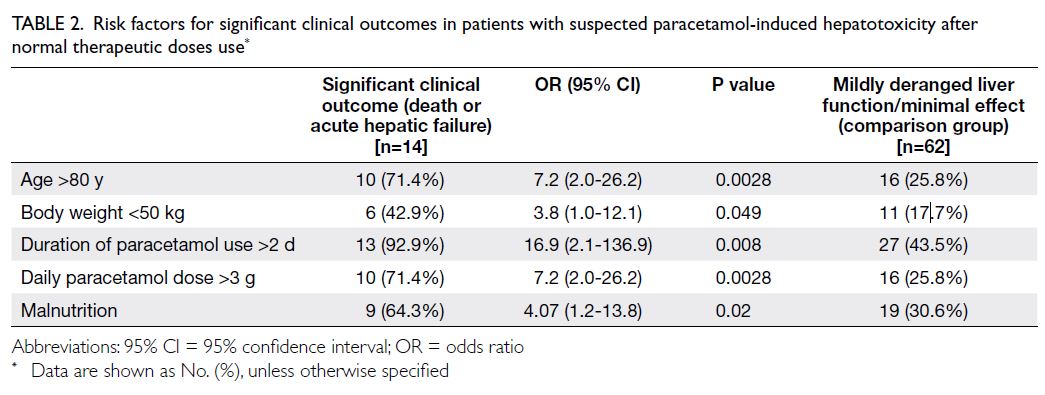

Patients with significant clinical outcomes

were evaluated by combining the death and

acute hepatic failure groups. Five risk factors for

significant clinical outcomes were identified, namely, age >80 years (odds ratio [OR]=7.2, 95% confidence

interval [CI]=2.0-26.2), body weight <50 kg (OR=3.8,

95% CI=1.0-12.1), duration of paracetamol use

>2 days (OR=16.9, 95% CI=2.1-136.9), daily

paracetamol dose >3 g (OR=7.2, 95% CI=2.0-26.2),

and malnutrition (OR=4.07, 95% CI=1.2-13.8). A

summary of the risk factors is provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Risk factors for significant clinical outcomes in patients with suspected paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity after normal therapeutic doses use

Discussion

The maximum recommended daily dose of

paracetamol for healthy adults is 4 g/day in

divided doses.17 As one of the most widely used

analgesics worldwide for decades, this dosage

recommendation is considered safe and generally

has not been questioned by most healthcare

professionals. Physicians have been taught to

use the convenient dosing of 1-g paracetamol

four times daily as a first-line analgesic in adults.

Historically, paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity

was solely regarded as a consequence of overdose.

Paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity after normal

therapeutic doses use was considered a therapeutic

misadventure of doubtful existence.7 However, case reports of this adverse drug reaction were

published.6 7 8 The situation becoming clear after a

single-blind randomised controlled trial by Watkins

et al18 revealed elevated ALT levels in 40% of healthy

individuals who had received 4 g/day of paracetamol

for 2 weeks. Subsequent studies confirmed this

observation and showed that continuous use of

paracetamol by individuals with high ALT levels

did not result in hepatotoxicity.19 20 Their ALT levels

returned to baseline after continuous paracetamol

use, suggesting hepatic adaptation.21 Nevertheless,

the mechanisms underlying hepatic adaptation are

not fully understood, and paracetamol-induced

hepatotoxicity after normal therapeutic doses use

may represent a rare adverse drug reaction due to

failed hepatic adaptation. In a prospective study in

Spain,22 the incidence of this adverse drug reaction

was estimated to be 10 per million paracetamol

users-year (95% CI=4.3-19.4). Prior to the present

study, there has been little information on how often

paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity occurs in the

Hong Kong Chinese population.

Our study confirmed the existence of this rare

adverse drug reaction, with an incidence of 1.2 cases of significant clinical outcomes per year in the Hong

Kong population (approximately 7 million people).

Because the vast majority of the local population is

served by public hospitals included in our poisoning

surveillance protocol, we believed that this figure

accurately reflects the rare occurrence of this adverse

drug reaction. Concerning patient characteristics

predictive of significant clinical outcomes, we found

that age >80 years, body weight <50 kg, duration of

paracetamol use >2 days, daily paracetamol dose

>3 g, and malnutrition were associated with a

higher risk of paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity

leading to death or acute hepatic failure. The median

daily dose was 4 g of paracetamol, consistent with

the convenient maximum therapeutic dosing (eg,

1 g four times daily) for adults. Additionally, the

median duration of paracetamol use was 5 to 7

days, indicating that life-threatening paracetamol-induced

hepatotoxicity can develop and rapidly

progress within a few days in susceptible individuals

receiving convenient paracetamol dosing. The

supratherapeutic serum paracetamol concentrations

detected in these cases provide evidence of impaired

hepatic paracetamol metabolism, leading to gradual

accumulation of paracetamol within the body. The

subsequent pathophysiology of hepatotoxicity

is considered identical to that of paracetamol

overdose. Therefore, the use of the antidote Nacetylcysteine

is recommended in all identifiable

cases of paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity after

normal therapeutic doses use.

One argument against the existence of this

adverse drug reaction has been the accuracy of

documentation concerning paracetamol dosage.7

Because the clinical presentation of paracetamol-induced

hepatotoxicity is indistinguishable from

that of paracetamol overdose, it has been suggested

that the hepatotoxicity cases actually represent

undeclared or undiagnosed instances of paracetamol

overdose, which are more common in clinical

practice. The present findings exclude this possibility.

All five patients who died had exhibited normal liver function upon or prior to hospital admission; they

were prescribed therapeutic doses of paracetamol for

various indications during their inpatient stay. The

possibility of intentional or accidental paracetamol

overdose was excluded in each case.

The association between older age and

paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity has been

addressed in previous studies. In 2021, a prospective

study by Louvet et al23 showed that older age was

an important risk factor associated with acute

liver injury after therapeutic doses of paracetamol.

Paracetamol pharmacokinetics in older adults

reportedly differ from those in younger adults.

Although absorption from the gastrointestinal tract

is not significantly reduced, paracetamol clearance is

46.8% lower in frail older individuals than in healthy

older individuals.24 In another observational study,25

the effects of ageing and frailty on serum paracetamol

and ALT levels were assessed in hospitalised patients

after continuous exposure to therapeutic doses for

5 days. The results showed that serum paracetamol

concentrations were higher in older frail patients.25

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, its

retrospective nature required reliance on the accuracy

and completeness of medical records. Incomplete

information in medical records, particularly missing

data concerning the daily dose and duration of

paracetamol exposure, could substantially affected

the results. Second, because all consultations were

voluntarily reported, underreporting may contribute

to reporting bias. Third, the sample size was relatively

small, hindering analysis of confounders via logistic

regression. Finally, the effects of some potential risk

factors (eg, chronic alcoholism and concomitant use

of P450 inducer) could not be quantified due to their

low reported incidence and the small sample size.

Conclusion

Paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity can occur at normal therapeutic doses in the Hong Kong

Chinese population. Our study identified risk

factors associated with significant clinical outcomes.

Considering the widespread use of paracetamol

in Hong Kong, the incidence of paracetamol-induced

hepatotoxicity is low; current dosage

recommendations are considered safe for the vast

majority of the general population. Nevertheless, a

maximum daily dose of ≤3 g is recommended for

susceptible patients. Paracetamol dosage, especially

if consumed at 4 g/day for >48 hours, should be

reviewed; liver function and INR monitoring should

be considered in susceptible patients.10

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: WH Tsang.

Analysis or interpretation of data: WH Tsang, CK Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: WH Tsang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual

content: WH Tsang, CK Chan.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Kowloon Central / Kowloon East Cluster Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: KC/KE-23-0041/ER-4). The

requirement for informed patient consent was waived by the

Committee due to the retrospective nature of the research

and the use of anonymised data in the research.

References

1. Finnerup NB. Nonnarcotic methods of pain management.

N Engl J Med 2019;380:2440-8. Crossref

2. Drug Office, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR

Government. List of Registered Over-the-counter

Pharmaceutical Products Containing Paracetamol. May

2023. Available from: https://www.drugoffice.gov.hk/eps/

do/en/doc/List_of_registered_pharmaceutical_products_

containing_paracetamol.pdf. Accessed 17 Sep 2023.

3. Joint Formulary Committee. Paracetamol. In: British

National Formulary. 78th ed. London: BNF Publications; 2019.

4. Burns MJ, Friedman SL, Larson AM. Acetaminophen

(paracetamol) poisoning in adults: pathophysiology,

presentation, and evaluation. August 2024. Available from:

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acetaminophen-paracetamol-poisoning-in-adults-pathophysiology-presentation-and-evaluation. Accessed 16 Sep 2024.

5. Prescott LF, Illingworth RN, Critchley JA, Stewart MJ, Adam RD, Proudfoot AT. Intravenous N-acetylcysteine: the

treatment of choice for paracetamol poisoning. Br Med J 1979;2:1097-100. Crossref

6. Kurtovic J, Riordan SM. Paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity at recommended dosage. J Intern Med 2003;253:240-3. Crossref

7. Prescott LF. Therapeutic misadventure with paracetamol:

fact or fiction? Am J Ther 2000;7:99-114. Crossref

8. Dom AM, Royzer R, Olson-Chen C. Malnourishment-associated

acetaminophen toxicity in pregnancy. Obstet

Gynecol 2021;137:877-80. Crossref

9. Health Services Safety Investigations Body. Investigation

report: unintentional paracetamol overdose in adult

inpatients with low bodyweight. February 2022. Available

from: https://www.hsib.org.uk/investigations-and-reports/unintentional-overdose-of-paracetamol-in-adults-with-low-bodyweight/unintentional-paracetamol-overdose-in-adult-inpatients-with-low-bodyweight/. Accessed 17 Sep 2023.

10. State of Queensland (Queensland Health), Queensland

Government, Australia. Guideline for Safe Paracetamol

Use. January 2023. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/1211443/guideline-safe-paracetamol-use.pdf. Accessed 17 Sep 2023.

11. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety

Communication: prescription acetaminophen products

to be limited to 325 mg per dosage unit; boxed warning

will highlight potential for severe liver failure. Available

from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-prescription-acetaminophen-products-be-limited-325-mg-dosage-unit. Accessed 1 Oct 2024.

12. Health Products Regulatory Authority. Summary of

product characteristics. Available from: https://www.hpra.ie/img/uploaded/swedocuments/Licence_PA22749-005-001_22072022162254.pdf. Accessed 1 Oct 2024.

13. Hong Kong Poison Control Centre, Hospital Authority.

Hong Kong Poison Information Centre. 2024. Available

from: https://www.pcc.org.hk/en-US/units/hk-poison-information-centre/. Accessed 2 Oct 2024.

14. Chow TY, Chan CK, Ng SH, Tse ML. Hong Kong Poison

Information Centre: annual report 2020. Hong Kong J

Emerg Med 2023;30:117-30. Crossref

15. Goldberg E, Chopra S, Rubin JN. Acute liver failure in

adults: etiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis.

December 2020. Available from: https://www.medilib.ir/uptodate/show/3574. Accessed 16 Sep 2024.

16. Bellanti F, Lo Buglio A, Quiete S, Vendemiale G.

Malnutrition in hospitalized old patients: screening and

diagnosis, clinical outcomes, and management. Nutrients

2022;14:910. Crossref

17. Drug Office, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Tips for using medicines containing

paracetamol. December 2023. Available from: https://www.drugoffice.gov.hk/eps/do/en/consumer/news_informations/knowledge_on_medicines/paracetamol.html. Accessed 16 Sep 2024.

18. Watkins PB, Kaplowitz N, Slattery JT, et al.

Aminotransferase elevations in healthy adults receiving 4

grams of acetaminophen daily: a randomized controlled

trial. JAMA 2006;296:87-93. Crossref

19. Heard K. Asymptomatic alanine aminotransferase

elevations with therapeutic doses of acetaminophen. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011;49:90-3. Crossref

20. Heard K, Green JL, Anderson V, Bucher-Bartelson B,

Dart RC. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial to

determine the course of aminotransferase elevation

during prolonged acetaminophen administration. BMC

Pharmacol Toxicol 2014;15:39. Crossref

21. Sonn BJ, Heard KJ, Heard SM, et al. Metabolomic markers

predictive of hepatic adaptation to therapeutic dosing of

acetaminophen. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2022;60:221-30. Crossref

22. Sabaté M, Ibáñez L, Pérez E, et al. Paracetamol in therapeutic

dosages and acute liver injury: causality assessment in a prospective case series. BMC Gastroenterol 2011;11:80. Crossref

23. Louvet A, Ntandja Wandji LC, Lemaître E, et al. Acute

liver injury with therapeutic doses of acetaminophen: a

prospective study. Hepatology 2021;73:1945-5. Crossref

24. Mian P, Allegaert K, Spriet I, Tibboel D, Petrovic M.

Paracetamol in older people: towards evidence-based

dosing? Drugs Aging 2018;35:603-24. Crossref

25. Mitchell SJ, Hilmer SN, Murnion BP, Matthews S.

Hepatotoxicity of therapeutic short-course paracetamol

in hospital inpatients: impact of ageing and frailty. J Clin

Pharm Ther 2011;36:327-35. Crossref