Hong Kong Med J 2024 Aug;30(4):310–9 | Epub 14 Aug 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

MEDICAL PRACTICE CME

Management of overactive bladder: consensus statements from the Hong Kong Urological Association and the Hong Kong Geriatrics Society

William KK Wong, MB, BS, FHKCP1; Raymond WM Kan, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)2; PS Lam, MB, BS, FHKCP3; Phoebe MH Cheung, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Surgery)4; Elaine YL Cheng, LMCHK, FHKCP5; Terrilyn CT Pun, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)6; Maria WS Tang, MB, ChB, FHKCP7; Clarence LH Leung, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Surgery)6; Sandy WS Woo, MB, BS, FHKCP8; TK Lo, MB, BS, FHKAM (Surgery)9; Peggy SK Chu, MB, BS, FCSHK9; Tony NH Chan, MB, BS, FHKCP10; Peter KF Chiu, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Surgery)11

1 Department of Medicine, Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Rehabilitation and Extended Care, Wong Tai Sin Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Tseung Kwan O Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

6 Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

7 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Shatin Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

8 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Ruttonjee Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

9 Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

10 Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, Pok Oi Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

11 SH Ho Urology Centre, Department of Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Peter KF Chiu (peterchiu@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a common urological

disease with a high prevalence in older adult

populations. Antimuscarinic drugs have been the

most common treatment for OAB for more than a

decade, but their anticholinergic side-effects and

potential impact on cognitive function among older

patients are usually underestimated. This consensus

aimed to provide practical recommendations

concerning OAB management, with a particular

emphasis on older patients. A joint consensus panel

was formed by representatives of the Hong Kong

Urological Association and the Hong Kong Geriatrics

Society. Literature searches regarding OAB and its

management were performed in PubMed and Ovid.

Several working meetings were held to present

and discuss available evidence, develop consensus

statements, and vote for the statements. A modified

Delphi method was used in this consensus process. To

address questions regarding various aspects of OAB,

29 consensus statements were proposed covering the

following areas: diagnosis, initial assessment, non-pharmacological

treatments, considerations before

administration of pharmacological treatments,

various pharmacological treatments, combination

therapy, and surgical treatment. Twenty-five

consensus statements were accepted.

Introduction

Overactive bladder (OAB) is defined by the

International Continence Society as urinary

urgency in the absence of urinary tract infection

or other detectable diseases, usually accompanied

by increased daytime frequency and/or nocturia,

with or without urinary incontinence.1 Its reported

prevalence ranges from 9.6% to 35.6%.2 A survey

in Hong Kong showed that the age-adjusted OAB

prevalence was 15.1%, and age was a significant risk

factor.3

Although many patients can benefit from

lifestyle modifications, medical therapy may

be warranted for patients with persistent and

bothersome OAB symptoms.4 Antimuscarinic

agents have been the most commonly prescribed

class of medications for OAB over the past two

decades.4 However, their anticholinergic effects on

cognitive function have long been both concerning

and underestimated. This is particularly significant

among older individuals because any cognitive

decline they experience could easily be attributed to normal ageing or dementia.5 Such cognitive decline

might be more pronounced when multiple drugs with

anticholinergic side-effects are used concurrently.5

The concept of anticholinergic burden has been

introduced to help clinicians estimate the combined

anticholinergic effects (and potential impact on

cognitive function) of all medications prescribed to

a single patient.5

Beta-3 agonists represent a new class of drugs

approved for the treatment of OAB.6 They do not

have any anticholinergic side-effects and have

therefore become alternatives to antimuscarinics for

the treatment of OAB, particularly among patients

with advanced age, dementia, or polypharmacy.6

To provide recommendations for the

treatment of OAB in Hong Kong, a joint consensus

panel was formed by representatives from the Hong

Kong Geriatrics Society (HKGS) and the Hong

Kong Urological Association (HKUA). Consensus

statements were produced based on the latest

evidence and international guidelines, supplemented

by expert opinions from panel members.

Methods

The joint consensus panel consisted of 13 experts

from Hong Kong: six geriatricians representing

the HKGS and seven urologists representing the

HKUA. Among these experts, seven were female

clinicians and six were male clinicians. In total,

seven meetings were held to discuss the scope of

the consensus, present key evidence, formulate

consensus statements, vote, and have a final

discussion regarding manuscript preparation.

Literature reviews were performed in PubMed

and Ovid to retrieve relevant articles related to this topic. The key words used included ‘overactive

bladder’, ‘anticholinergic’, ‘antimuscarinic’, ‘beta3-adrenoceptor agonist’, ‘β3-adrenoceptor agonist’,

‘β3 agonist’, ‘guidelines’, ‘behavioural therapy’,

‘behavioural treatment’, ‘combination therapy’,

and ‘surgery’. In total, 34 articles were selected for

presentation and in-depth discussion, including

four major guidelines, 15 meta-analyses/systematic

reviews, and 15 randomised controlled trials. When

discussing areas with inadequate evidence, the

modified Delphi method was used. Panel discussions

were carried out in a structured manner using

appropriate content; each panel member contributed

to the discussion in a fair and equal manner. The

discussion was divided into seven parts, namely,

introduction and overview of OAB, assessment

and diagnostic approaches, non-pharmacological

treatment, antimuscarinic agents, beta-3 agonists,

combination therapy, and surgical treatment for

OAB.

Panel members were divided into small

working subgroups to review the existing literature,

present their findings to other panel members, draft

consensus statements, and finalise the consensus

statements during panel meetings. In the last

meeting, panellists voted anonymously on the

practicability of recommendation in Hong Kong

for each statement, based on predefined judgement

criteria (online supplementary Table 1). If ≥75%

of panellists chose ‘accept completely’ (option A)

or ‘accept with some reservations’ (option B), a

consensus statement was regarded as accepted. A

total of 29 consensus statements were proposed,

and 25 of them were accepted. The complete voting

record and all consensus statements are listed in

online supplementary Table 2.

The AGREE (Appraisal of Guidelines,

Research and Evaluation) reporting guideline

was used to ensure the methodological quality,

comprehensiveness, completeness, and transparency

of this consensus document.

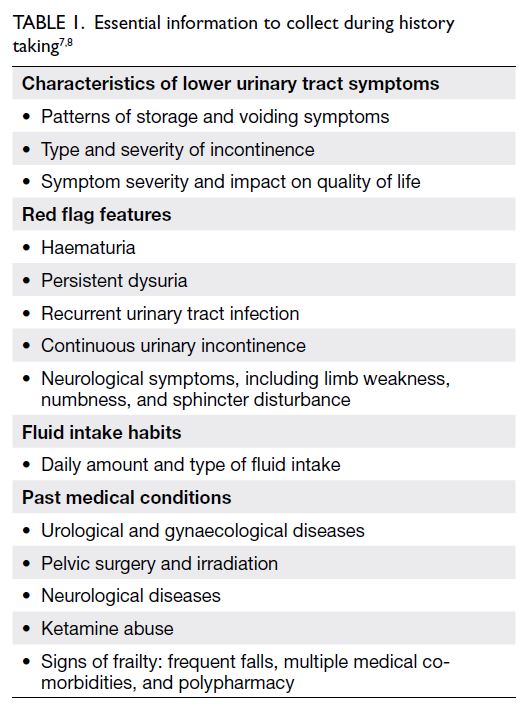

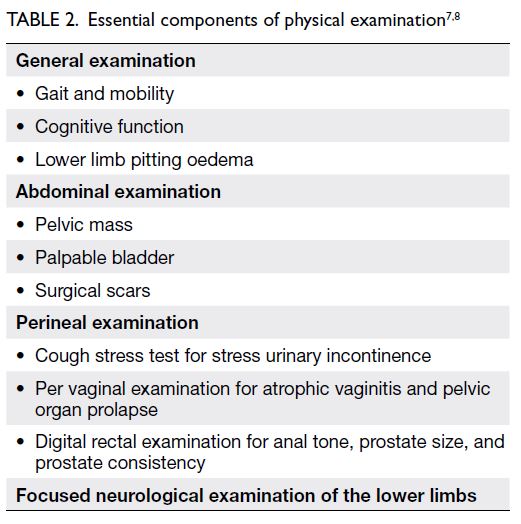

History and physical examination

The initial assessment is intended to diagnose OAB, rule out other pathologies, assess symptom severity, and formulate an individualised management plan.

Statement 1: The clinician should begin the diagnostic process with careful history taking and physical examination.

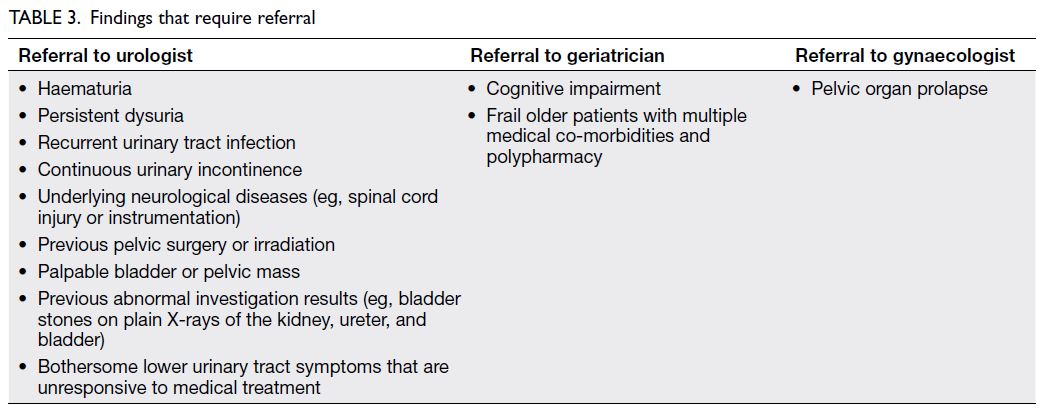

Statement 2: Storage lower urinary tract symptoms may be a sign of more serious underlying conditions, and their management can be complicated by co-morbidities and polypharmacy. The clinician should seek a specialist’s opinion if red flag features are detected.

History taking and focused physical examination are important in the assessment of storage lower urinary tract symptoms7 8 (Tables 1 and 2). Patients with alarming symptoms should be

referred to relevant specialists (Table 3). Past health

also provides clues to the aetiology of the problem.

In particular, medical diseases including diabetes

mellitus, fluid status, obstructive sleep apnoea,

as well as their treatments, can contribute to such

symptoms.

Symptom severity can be assessed by the

number of pads used per day, degree of restriction

in daily activities, and presence or absence of

psychological stress.7 8 Assessments of frailty,

cognitive function, and anticholinergic burden are

especially relevant in older individuals, considering

their implications for subsequent management.

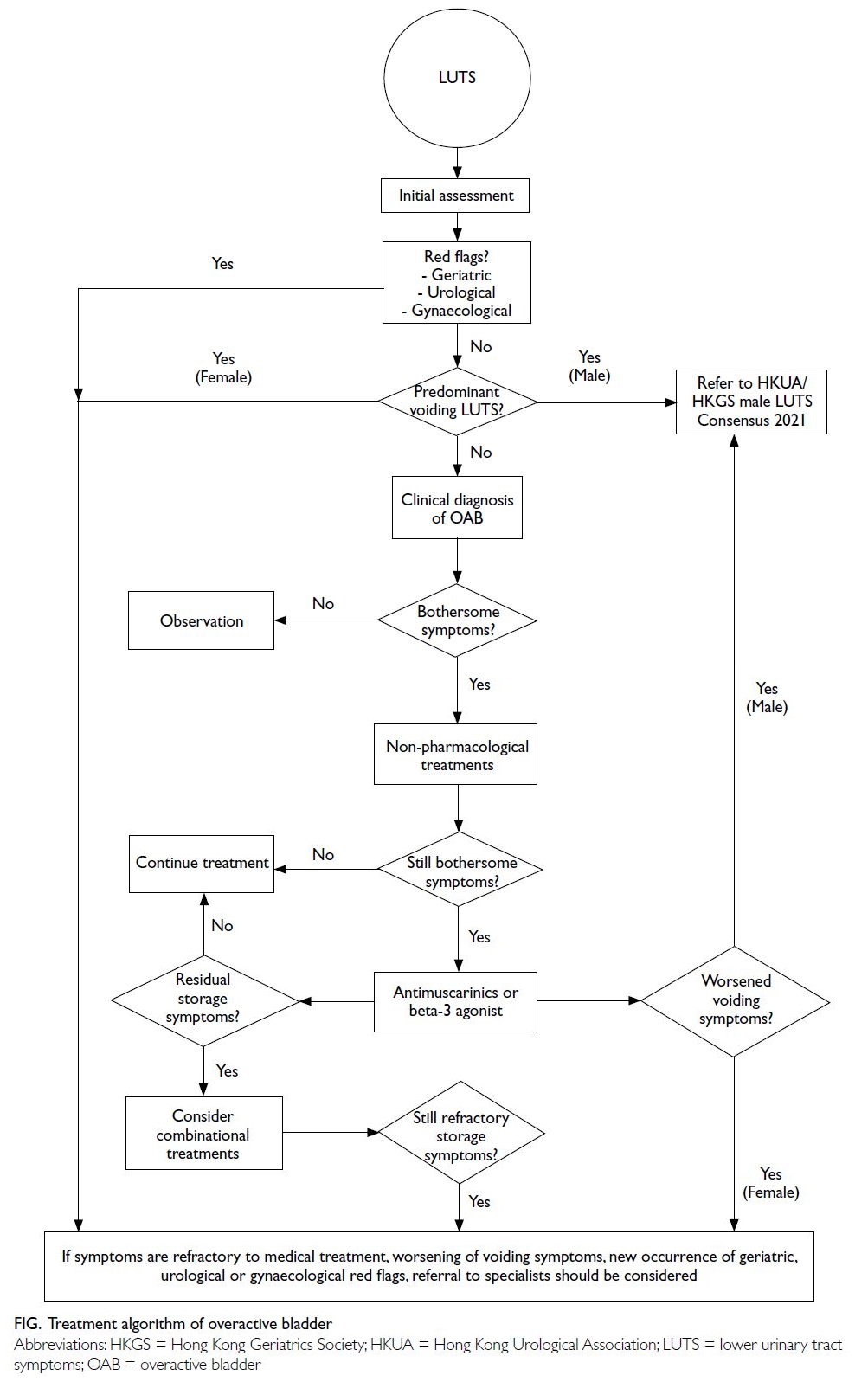

The treatment algorithm for OAB is illustrated in the Figure.

Investigations

Statement 3: Urinalysis should be considered during the initial assessment of overactive bladder syndrome.

Urinalysis is recommended as an initial

assessment for patients with OAB in most guidelines,

including the European Association of Urology 2023

guidelines on lower urinary tract symptoms7 8; the

results can rule out urinary tract infection, diabetes

mellitus, and proteinuria.7 8

Statement 4: A bladder diary should be considered during the assessment of overactive bladder syndrome.

A bladder diary serves as documentation

of the patient’s drinking habits, voiding patterns,

and incontinence episodes. It is useful for OAB

diagnosis, baseline symptom quantification,

treatment response monitoring, and bladder training

programme planning.

Statement 5: Urine culture, post-void residual urine, plain X-rays of the kidney, ureter, and bladder, and patient questionnaires may be performed during the initial assessment of overactive bladder syndrome at the clinician’s discretion.

Statement 6: If questionnaires are used for assessment of overactive bladder syndrome, appropriate questionnaires validated in the patient’s language should be used.

Statement 7: Cystoscopy, urodynamics, ultrasonography of the urinary system, and pad tests should not be routinely included in the initial assessment of overactive bladder syndrome.

Urine culture, post-void residual urine,

plain X-rays of the kidney, ureter, and bladder, and

symptom/quality of life questionnaires are not

considered routine tests in the initial assessment.

Questionnaires including the OAB Symptom Score,

Urogenital Distress Inventory-6, and Incontinence

Impact Questionnaire, Short Form have been

validated in Cantonese within Hong Kong. The

OAB Symptom Score is a screening tool used to

measure symptom severity in both male and female

patients, whereas Urogenital Distress Inventory-6

and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire, Short Form are used to measure symptom distress and health-related

quality of life in female patients. Cystoscopy,

urodynamics, ultrasonography of the urinary system,

and pad tests are not recommended for the initial

assessment of OAB in most guidelines.

Treatment

Non-pharmacological treatments

Statement 8: Non-pharmacological treatments, including fluid management, bladder training, and pelvic floor exercises, should be offered to patients with overactive bladder, regardless of drug treatment initiation.

Statement 9: Clinicians should identify medications and substances that may contribute to overactive bladder and consider modifications or alternatives.

Fluid management comprising a 25% decrease

in fluid intake can reduce urination frequency

and urgency.9 Reduced liquid consumption after

dinner or within several hours before bedtime is

a reasonable management approach for nocturia.

Caffeine irritates the bladder and can induce urinary

urgency; therefore, caffeine intake should be avoided.

Some drugs (eg, diuretics and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors) may worsen OAB

symptoms; the use of these drugs should be identified,

and the patient should be switched to a suitable

alternative. Additionally, angiotensin-converting

enzyme inhibitors can induce coughing, thereby

exacerbating urinary incontinence. Sodium-glucose

cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors cause increased

urine output and higher urinary frequency; thus,

they should be avoided.

Statement 10: Weight reduction should be advised for obese individuals with overactive bladder.

Among obese women, weight loss of 8.0%

reduces the overall amounts of weekly incontinence

episodes by 47% (vs 28% in the control group) and urgency urinary incontinence episodes by 42% (vs 26% in the control group) within 6 months.10

Statement 11: For patients who have difficulty performing pelvic floor exercises and bladder

training, early pharmacological therapy should be considered.

Behavioural therapy and bladder training are

recommended as conventional approaches before

considering drug treatment; the success of these

approaches requires active participation by patients

and their caregivers. Upfront pharmacological

therapy may be considered for patients (especially

frail older individuals) who have difficulty complying

with these approaches.

Statement 12: Before initiating treatment, clinicians should educate patients and caregivers about the symptoms and natural course of overactive bladder, and the benefits and risks of currently available treatments.

Before drug treatment is initiated, the natural

course of the disease and the safety profiles of

various treatment options should be explained to

increase patient compliance. Clinicians should

establish feasible treatment goals with patients and

their caregivers.

Statement 13: Antimuscarinics should be used cautiously in patients with cognitive impairment or a high anticholinergic burden.

Statement 14: Because polypharmacy is very common, a detailed review of drug history is recommended to avoid creating a clinically significant anticholinergic burden in patients.

Cognitive impairment (eg, delirium

and dementia) has been linked to the use of

antimuscarinic agents, particularly in older

patients.11 It is important to review drug history before prescribing antimuscarinics to this group of

patients. The concurrent use of medications with

anticholinergic effects, such as antihistamines and

anti-Parkinson’s drugs, may potentiate the side-effects

of antimuscarinic agents and should be

modified accordingly.

Pharmacological treatment

Antimuscarinic agents

Randomised controlled trials have revealed

improvements in symptom control and differences

in the cure rates of urgency incontinence when using

antimuscarinic agents. However, no single agent has

demonstrated superiority over the others in terms of

efficacy.12 13

Statement 15: Antimuscarinics should be offered to patients who have been unsuccessful with non-pharmacological approaches.

Statement 16: Extended-release antimuscarinics are preferred over immediate-release antimuscarinics because of better tolerability, particularly regarding

dry mouth.

Statement 17: Antimuscarinics should not be used in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma unless approved by an ophthalmologist.

The overall withdrawal rates of antimuscarinic

agents due to side-effects range from 3% to 10%.14

Adverse events include dry mouth, pruritus, blurred

vision, and dizziness (29.6%, 15.4%, 3.8%, and

3.5%, respectively).14 The results of a meta-analysis

suggested that extended-release formulations

have lower rates of adverse events, particularly dry

mouth.14 However, the rates of constipation and

withdrawal due to side-effects are not significantly

different between immediate-release and extended-release

formulations. Notably, antimuscarinics can

cause pupil dilation and precipitate closed-angle

glaucoma, particularly among patients with narrow-angle

glaucoma.15

Statement 18: Antimuscarinics are effective in treating overactive bladder but regular monitoring of voiding symptoms is recommended, especially among older individuals.

The use of antimuscarinic agents is associated

with a minimal increase in post-void residual urine

volume among male patients. In a study of men with

proven bladder outlet obstruction, this increase in

post-void residual urine volume did not lead to acute

urinary retention.16 Nevertheless, changes in voiding

symptoms after the initiation of antimuscarinic

agents, particularly among older patients, should be

monitored.

As a quaternary amine compound with

hydrophilic properties, trospium has a theoretical advantage in that it does not cross the blood-brain

barrier and therefore may result in less cognitive

impairment. There is evidence to support the claim

that trospium does not worsen cognitive function in

patients with Alzheimer’s disease.17 A pooled analysis

indicated that trospium has a lower treatment

withdrawal rate due to side-effects compared with

other anticholinergics.18 However, there remains

a lack of strong evidence concerning the degree

of cognitive decline from various anticholinergic

agents.

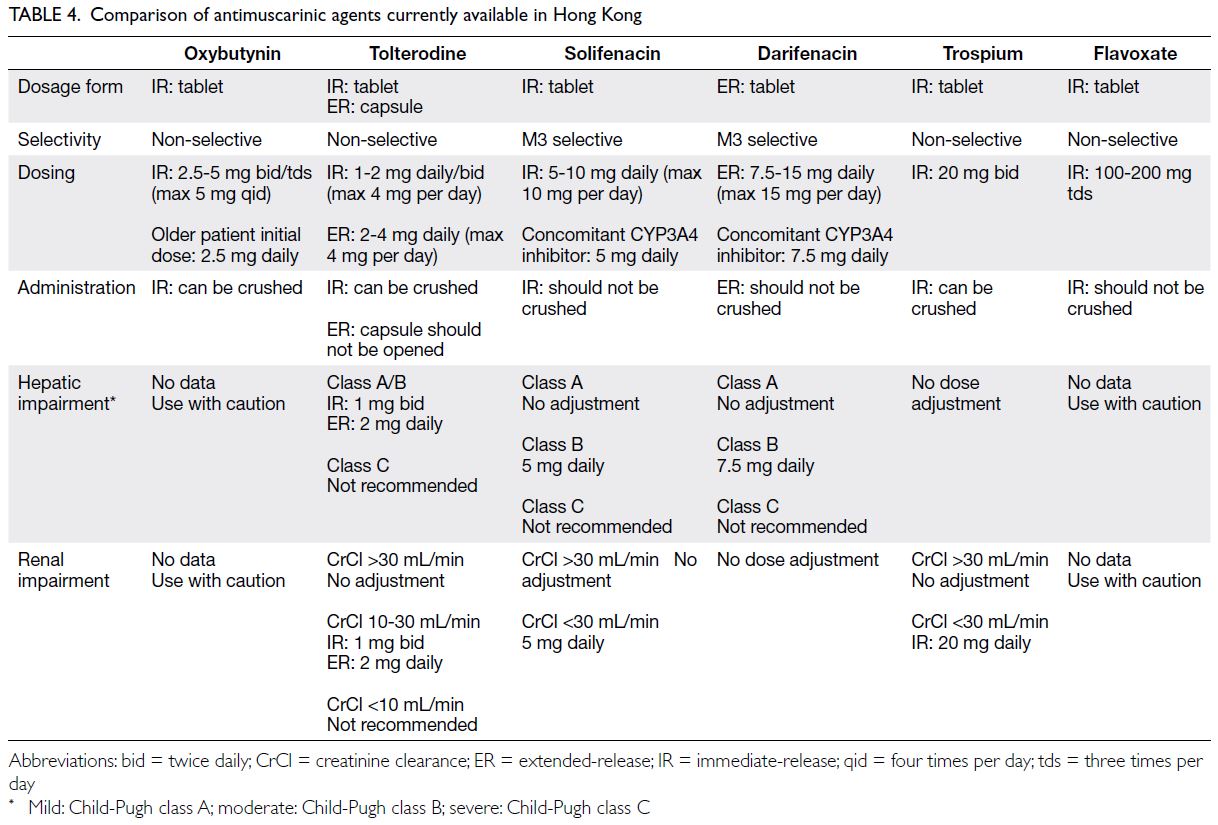

Antimuscarinic agents registered for the

treatment of OAB in Hong Kong are listed in Table 4.

Beta-3 agonists

Statement 19: Beta-3 agonists provide overall efficacy similar to that of commonly used antimuscarinic monotherapies.

Beta-3 adrenoceptor agonists (ie, mirabegron

and vibegron) relax detrusor muscles in the urinary

bladder wall, allowing the bladder to remain

distended during the storage phase. Mirabegron

significantly improved incontinence episodes and

micturition frequency compared with placebo in a

phase 3 trial.19 The efficacy of mirabegron 50 mg is

similar to that of most antimuscarinic monotherapies

regarding micturition frequency, urgency urinary

incontinence, dry rate, and 50% reduction in

incontinence episodes.20 Mirabegron is efficacious in

improving OAB symptoms and quality of life.21 22

Statement 20: Beta-3 agonists appear to be better tolerated than antimuscarinics (eg, in terms of dry mouth, constipation, and urinary retention).

Compared with antimuscarinic monotherapy,

mirabegron is better tolerated and has significantly

lower risks of dry mouth, constipation, and urinary

retention. This safety profile remains consistent for

up to 1 year of treatment.22 Mirabegron also has

better treatment persistence and adherence rates

at 12 months.22 Therefore, mirabegron can serve as

an alternative pharmacological treatment for older

patients with OAB.23 24

Statement 21: Mirabegron should not be used in patients with severely uncontrolled hypertension.

According to recommendations from

the United Kingdom25 and European26 health

authorities, mirabegron is contraindicated in

patients with severely uncontrolled hypertension

(ie, systolic blood pressure ≥180 mm Hg and/or

diastolic blood pressure ≥110 mm Hg) due to the

lack of studies concerning mirabegron effects in this

group of patients. However, in a phase 3 randomised

controlled trial comparing mirabegron 25 mg,

mirabegron 50 mg, and placebo, the incidence

of hypertension was similar across all subgroups (12%, 11%, and 8.5%, respectively).19 Additionally,

the adjusted mean changes in systolic and diastolic

blood pressures from baseline to the final visit were

comparable between the mirabegron 25 mg and

placebo groups. Patients in the mirabegron 50 mg

group experienced a clinically insignificant increase

in blood pressure (ie, 1.0-1.5 mm Hg) compared with

the placebo group.19

Combination therapy

Statement 22: Combination drug treatment (a beta-3 agonist and an antimuscarinic agent) may be considered for overactive bladder that is unresponsive to monotherapy with either antimuscarinics or beta-3 agonists.

Several trials have investigated the use

of combination drug therapy comprising an

antimuscarinic agent and a beta-3 agonist,

especially solifenacin and mirabegron, in patients

with OAB.20 21 In the SYMPHONY study, three

combination groups (solifenacin 10 mg/mirabegron

25 mg, solifenacin 5 mg/mirabegron 50 mg, and

solifenacin 10 mg/mirabegron 50 mg) displayed

significant improvements in mean volume voided per micturition, micturition frequency, and

urgency episodes compared with solifenacin 5

mg monotherapy.27 Despite a slight increase in

the incidence of constipation among combination

groups using solifenacin 10 mg, combination drug

treatments were well tolerated compared with

monotherapy or placebo.

In the SYNERGY study, the combination of

solifenacin 5 mg/mirabegron 50 mg was superior to

solifenacin or mirabegron monotherapy in terms of

reducing incontinence episodes, urgency episodes,

and nocturia.28 In two other studies (BESIDE29 and

MILAI30), mirabegron was used as an add-on therapy

for patients with OAB who remained symptomatic

on solifenacin alone. Both studies showed that the

combination of solifenacin 5 mg/mirabegron 50 mg

produced greater improvements in incontinence

episodes and micturition frequency.29 30 The

incidence and frequency of treatment-emergent

adverse events were similar in the combination and

monotherapy groups. The withdrawal rate related to

treatment-emergent adverse events was low (ie, 1.1%

to 1.5%).29 30

The long-term safety and efficacy of solifenacin

and mirabegron combination treatment over 12 months were demonstrated in the SYNERGY II31 and

MILAI II studies,32 and the use of antimuscarinics

other than solifenacin in combination therapy was

assessed in the MILAI II study.32 Similar efficacy

and adverse events were observed with various

combinations of antimuscarinics (eg, imidafenacin,

propiverine, and tolterodine) and mirabegron.

Statement 23: Combination treatment using a beta-3 agonist and an antimuscarinic is preferred over the use of two antimuscarinics due to fewer side-effects and a lower anticholinergic burden.

There is a lack of large-scale randomised

controlled trials evaluating combination therapy

with two antimuscarinic agents. In a retrospective

study, the long-term persistence rate for combination

therapy with two antimuscarinics was poor due

to adverse events.20 In contrast, the combination

of an antimuscarinic agent and a beta-3 agonist

exhibited a better persistence rate compared with

monotherapy among patients with OAB who had

moderate to severe symptoms.20 21 Considering the

high anticholinergic burden in older individuals, the

use of two antimuscarinics is not preferable, even if

the response to monotherapy is inadequate. Instead,

combination therapy with an antimuscarinic agent

and a beta-3-agonist is recommended.

Surgical treatment

Statement 24: Posterior tibial nerve stimulation should be considered for patients who have been unsuccessful with pharmacological treatment.

Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS)

is a less invasive procedure among the available

surgical interventions for OAB. A meta-analysis

involving 2461 patients showed that PTNS could

reduce voiding frequency, nocturia frequency,

urgency episodes, and incontinence episodes while

increasing the maximum cystometric capacity.33

The main complication was pain at the puncture

site, but its incidence was low. One trial comparing

the efficacies of PTNS and tolterodine showed that

PTNS had superior results concerning the composite

outcome of cure or symptom improvement (79.5%

vs 54.8%; P=0.01).34 Trials comparing PTNS with

beta-3 agonists are ongoing.

Statement 25: Intravesical botulinum toxin injection or sacral neuromodulation should be considered in carefully selected patients who have been unsuccessful with pharmacological treatment.

A phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled

trial demonstrated that intravesical injection of

botulinum toxin A significantly reduced micturition

frequency, increased the rate of complete continence,

and improved OAB symptoms and quality of life

scores compared with placebo.35 The clinical effects of botulinum toxin A usually persisted for 3 months

to 1 year, and additional injections were needed when

the effects diminished. Uncomplicated urinary tract

infection was the most common adverse event, and

urinary retention was observed in 5.4% of patients.35

Sacral neuromodulation (SNM) utilises a

principle similar to PTNS but involves implantation

of electrical leads at the S3 nerve root.36 A systematic

review showed that 15% of patients were completely

cured with SNM, whereas 50% of patients had a >90%

reduction in the number of incontinence episodes.36

The most common complications associated with

SNM were pain at the implant or lead site (25%), lead

migration (16%), and replacement and repositioning

of the implanted pulse generator (15%).36 Pain at

the implant or lead site is similar to sciatica, which

radiates down to the lower back to the hip, thigh,

and toes. A test implant is generally required. If the

pain is intolerable, permanent implantation is not

performed.

Conclusion

Overactive bladder is a common condition with a

substantial impact on quality of life. The number of

patients with increasing OAB complexity is expected

to increase due to population ageing. Representatives

of the HKGS and the HKUA have agreed upon 25

consensus statements regarding the diagnostic

approach, management, and referral mechanism for

OAB in primary care settings. Through collaborations

among primary care practitioners, geriatricians, and

urologists, we hope to provide more holistic care to

patients with OAB in Hong Kong.

Author contributions

Concept or design: PSK Chu, WKK Wong, TNH Chan, RWM Kan.

Acquisition of data: RWM Kan, PS Lam, PMH Cheung, TCT Pun, TK Lo.

Analysis or interpretation of data: EYL Cheng, MWS Tang, SWS Woo, CLH Leung.

Drafting of the manuscript: TCT Pun, TNH Chan, WKK Wong, PKF Chiu.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: PSK Chu, WKK Wong, PKF Chiu.

Acquisition of data: RWM Kan, PS Lam, PMH Cheung, TCT Pun, TK Lo.

Analysis or interpretation of data: EYL Cheng, MWS Tang, SWS Woo, CLH Leung.

Drafting of the manuscript: TCT Pun, TNH Chan, WKK Wong, PKF Chiu.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: PSK Chu, WKK Wong, PKF Chiu.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and some information may not have been peer reviewed. Accepted

supplementary material will be published as submitted by the

authors, without any editing or formatting. Any opinions

or recommendations discussed are solely those of the

author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy

of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association.

The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong

Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility

arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. D’Ancoa C, Haylen B, Oelke M, et al. The International

Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for

adult male lower urinary tract and pelvic floor symptoms

and dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn 2019;38:433-77. Crossref

2. Eapen RS, Radomski SB. Review of the epidemiology of

overactive bladder. Res Rep Urol 2016;8:71-6. Crossref

3. Yee CH, Chan CK, Teoh JY, et al. Survey on prevalence

of lower urinary tract symptoms in an Asian population.

Hong Kong Med J 2019;25:13-20. Crossref

4. DB Ng, McCart M, Klein C, Campbell C, Schoenhaus R,

Berner T. Evaluating outcomes in patients with overactive

bladder within an integrated healthcare delivery system

using a treatment patterns analyzer. Am Health Drug

Benefits 2016;9:343-53.

5. Kraus SR, Bavendam T, Brake T, Griebling TL. Vulnerable

elderly patients and overactive bladder syndrome. Drugs

Aging 2010;27:697-713. Crossref

6. Bragg R, Hebel D, Vouri SM, Pitlick JM. Mirabegron: a

beta-3 agonist for overactive bladder. Consult Pharm

2014;29:823-37. Crossref

7. European Association of Urology. Guidelines for non-neurogenic

female LUTS. Available from: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/non-neurogenic-female-luts/chapter/introduction. Accessed 1 Jun 2023.

8. European Association of Urology. Guidelines for

management of non-neurogenic male LUTS. Available

from: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/management-of-non-neurogenic-male-luts/chapter/introduction. Accessed 1 Jun 2023.

9. Hashim H, Abrams P. How should patients with an overactive bladder manipulate their fluid intake? BJU Intl 2008;102:62-6. Crossref

10. Subak LL, Wing R, West DS, et al. Weight loss to treat urinary incontinence in overweight and obese women. N Eng J Med 2009;360:481-90. Crossref

11. Painter CE, Suskind AM. Advances in pharmacotherapy

for the treatment of overactive bladder. Curr Bladder

Dysfunct Rep 2019;14:377-84. Crossref

12. Chapple C, Khullar V, Gabriel Z, Dooley JA. The effects

of antimuscarinic treatments in overactive bladder: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol 2005;48:5-26. Crossref

13. Chapple CR, Khullar V, Gabriel Z, Muston D, Bitoun CE,

Weinstein D. The effects of antimuscarinic treatments in

overactive bladder: an update of a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Eur Urol 2008;54:543-62. Crossref

14. Khullar V, Chapple C, Gabriel Z, Dooley JA. The effects

of antimuscarinics on health-related quality of life in

overactive bladder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urology 2006;68(2 Suppl):38-48. Crossref

15. Khurana AK, Khurana B, Khurana AK. Drug-induced

angle-closure glaucoma. J Curr Glaucoma Pract 2012;6:6-8. Crossref

16. Abrams P, Kaplan S, de Koning Gans HJ, Millard R.

Safety and tolerability of tolterodine for the treatment of

overactive bladder in men with bladder outlet obstruction.

J Urol 2006;175:999-1004. Crossref

17. Isik AT, Celik T, Bozoglu E, Doruk H. Trospium and

cognition in patients with late onset Alzheimer disease. J

Nutr Health Aging 2009;13:672-6. Crossref

18. Madhuvrata P, Cody JD, Ellis G, Herbison GP, Hay-Smith EJ. Which anticholinergic drug for overactive bladder symptoms in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2012;(1):CD005429. Crossref

19. Herschorn S, Barkin J, Castro-Diaz D, et al. A phase III,

randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled,

multicentre study to assess the efficacy and

safety of the β3 adrenoceptor agonist, mirabegron, in

patients with symptoms of overactive bladder. Urology

2013;82:313-20. Crossref

20. Wani MM, Sheikh MI, Bhat T, Bhat Z, Bhat A. Comparison

of antimuscarinic drugs to beta adrenergic agonists in

overactive bladder: a literary review. Curr Urol 2021;15:153-

60. Crossref

21. Kelleher C, Hakimi Z, Zur R, et al. Efficacy and

tolerability of mirabegron compared with antimuscarinic

monotherapy or combination therapies for overactive

bladder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis.

Eur Urol 2018;74:324-33. Crossref

22. Chapple CR, Siddiqui E. Mirabegron for the treatment

of overactive bladder: a review of efficacy, safety and

tolerability with a focus on male, elderly and antimuscarinic

poor-responder populations, and patients with OAB in

Asia. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2017;10:131-51. Crossref

23. Nakagomi H, Mitsui T, Shimura H, et al. Mirabegron

for overactive bladder in frail patients 80 years or over

(HOKUTO study). BMC Urol 2022;22:40. Crossref

24. Herschorn S, Staskin D, Schermer CR, Kristy RM, Wagg A.

Safety and tolerability results from the PILLAR study: a

phase IV, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled

study of mirabegron in patients ≥ 65 years with overactive

bladder-wet. Drugs Aging 2020;37:665-76. Crossref

25. GOV.UK. Mirabegron (Betmiga▼): risk of severe hypertension and associated cerebrovascular and cardiac events. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/mirabegron-betmiga-risk-of-severe-hypertension-and-associated-cerebrovascular-and-cardiac-events. Accessed 1 Jun 2023.

26. European Medicines Agency. Assessment report of Betmiga (mirabegron). 2012. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/betmiga-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf. Accessed 1 Jun 2023.

27. Abrams P, Kelleher C, Staskin D, et al. Combination

treatment with mirabegron and solifenacin in patients

with overactive bladder: exploratory responder analyses of

efficacy and evaluation of patient-reported outcomes from

a randomized, double-blind, factorial, dose-ranging, phase

II study (SYMPHONY). World J Urol 2017;35:827-38. Crossref

28. Herschorn S, Chapple CR, Abrams P, et al. Efficacy and

safety of combinations of mirabegron and solifenacin

compared with monotherapy and placebo in patients

with overactive bladder (SYNERGY study). BJU Int 2017;120:562-75. Crossref

29. Drake MJ, Chapple C, Esen AA, et al. Efficacy and safety

of mirabegron add-on therapy to solifenacin in incontinent

overactive bladder patients with an inadequate response

to initial 4-week solifenacin monotherapy: a randomised

double-blind multicentre phase 3B study (BESIDE). Eur

Urol 2016;70:136-45. Crossref

30. Yamaguchi O, Kakizaki H, Homma Y, et al. Safety and

efficacy of mirabegron as ‘add-on’ therapy in patients

with overactive bladder treated with solifenacin: a postmarketing,

open-label study in Japan (MILAI study). BJU

Int 2015;116:612-22. Crossref

31. Gratzke C, van Maanen R, Chapple C, et al. Long-term

safety and efficacy of mirabegron and solifenacin in

combination compared with monotherapy in patients with

overactive bladder: a randomised, multicentre phase 3

study (SYNERGY II). Eur Urol 2018;74:501-9. Crossref

32. Yamaguchi O, Kakizaki H, Homma Y, et al. Long-term

safety and efficacy of antimuscarinic add-on therapy in

patients with overactive bladder who had a suboptimal response to mirabegron monotherapy: a multicenter,

randomized study in Japan (MILAI II study). Int J Urol

2019;26:342-52. Crossref

33. Wang M, Jian Z, Ma Y, Jin X, Li H, Wang K. Percutaneous

tibial nerve stimulation for overactive bladder syndrome:

a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J

2020;31:2457-71. Crossref

34. Peters KM, Macdiarmid SA, Wooldridge LS, et al.

Randomized trial of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation

versus extended-release tolterodine: results from the

overactive bladder innovative therapy trial. J Urol

2009;182:1055-61. Crossref

35. Nitti VW, Dmochowski R, Herschorn S, et al.

OnabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of patients with

overactive bladder and urinary incontinence: results of

a phase 3, randomized, placebo controlled trial. J Urol

2017;197(2S):S216-23. Crossref

36. Brazzelli M, Murray A, Fraser C. Efficacy and safety of

sacral nerve stimulation for urinary urge incontinence: a

systematic review. J Urol 2006;175:835-41. Crossref