Hong Kong Med J 2024 Aug;30(4):300–9 | Epub 15 Aug 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

End-of-life practices in Hong Kong intensive care

units: results from the Ethicus-2 study

Gavin Matthew Joynt, MBBCh, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)1; Steven KH Ling, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)2; LL Chang, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)3; Polly NW Tsai, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)4; Gary KF Au, MB, ChB, FHKAM (Medicine)5; Dominic HK So, MB, BS, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)6; FL Chow, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)7; Philip KN Lam, MB, BS, FHKAM (Medicine)8; Alexander Avidan, MD9; Charles L Sprung, MD9; Anna Lee, MPH, PhD1; Hong Kong Ethicus-2 study Group

for the Hong Kong Ethicus-2 study group (group members are listed at the end of the article)

1 Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Intensive Care, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Intensive Care, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Adult Intensive Care Unit, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Department of Intensive Care, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

6 Department of Intensive Care Unit, Princess Margaret Hospital/Yan Chai Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

7 Department of Intensive Care, Caritas Medical Centre, Hong Kong SAR, China

8 Department of Intensive Care, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

9 Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Hadassah Medical Organization and Faculty of Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

Corresponding author: Prof Gavin Matthew Joynt (gavinmjoynt@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The need for end-of-life care is

common in intensive care units (ICUs). Although

guidelines exist, little is known about actual end-of-life care practices in Hong Kong ICUs. The study

aim was to provide a detailed description of these

practices.

Methods: This prospective, multicentre

observational sub-analysis of the Ethicus-2 study

explored end-of-life practices in eight participating

Hong Kong ICUs. Consecutive adult ICU patients

admitted during a 6-month period with life-sustaining

treatment (LST) limitation or death were

included. Follow-up continued until death or 2

months from the initial decision to limit LST.

Results: Of 4922 screened patients, 548 (11.1%) had

LST limitation (withholding or withdrawal) or died

(failed cardiopulmonary resuscitation/brain death).

Life-sustaining treatment limitation occurred in

455 (83.0%) patients: 353 (77.6%) had decisions

to withhold LST and 102 (22.4%) had decisions to

withdraw LST. Of those who died without LST

limitation, 80 (86.0%) had failed cardiopulmonary

resuscitation and 13 (14.0%) were declared brain

dead. Discussions of LST limitation were initiated

by ICU physicians in most (86.2%) cases. Shared

decision-making between ICU physicians and

families was the predominant model; only 6.0%

of patients retained decision-making capacity.

Primary medical reasons for LST limitation were

unresponsiveness to maximal therapy (49.2%) and

multiorgan failure (17.1%). The most important

consideration for decision-making was the patient’s

best interest (81.5%).

Conclusion: Life-sustaining treatment limitations

are common in Hong Kong ICUs; shared decision-making between physicians and families in the

patient’s best interest is the predominant model. Loss

of decision-making capacity is common at the end of

life. Patients should be encouraged to communicate

end-of-life treatment preferences to family members/surrogates, or through advance directives.

New knowledge added by this study

- Life-sustaining treatment (LST) limitation at the end of life is common in Hong Kong intensive care units (ICUs).

- Compared with international practices, the time from admission to LST limitation is relatively long in Hong Kong.

- Shared decision-making between healthcare providers and patients, family members, or patient surrogates is the predominant decision-making model.

- Most patients lack the mental capacity for decision-making at the end of life.

- Patient preferences regarding the use of life-sustaining therapies at the end of life are usually unknown, and the use of advance directives is rare.

- End-of-life care practices in Hong Kong ICUs generally align with local guidelines and the international consensus.

- Local factors possibly preventing earlier implementation of LST limitation in appropriate patients should be explored.

- The public should be educated to communicate their preferences regarding the use of life-sustaining therapies in ICUs to surrogates/family members, or through advance directives.

Introduction

Despite high-quality care, many patients admitted

to the intensive care unit (ICU) do not survive;

therefore, management of the dying process

is a required skill among modern healthcare

professionals.1 Life-sustaining technology has

advanced sufficiently that it is possible to maintain

vital organ function despite the knowledge that the

patient’s return to health and an acceptable quality

of life is no longer feasible. In these situations, a

decision to limit life-sustaining treatment (LST) has

become a common clinical practice in most countries

worldwide.2 3 4 5 6 In recent decades, attempts to define desirable principles for end-of-life care according

to a global professional consensus have achieved

considerable success.3 Nevertheless, decision-making

processes for death and dying are likely to

be heavily influenced by regional and cultural norms

and expectations; thus, it is reasonable to expect

different medical practices related to end-of-life

decisions. Several local and international surveys

of healthcare professionals have revealed regional

differences in attitudes towards end-of-life ethical

concerns, as well as substantial differences in clinical

practices.7 8 9 10 11 Limited prospective observational data from international studies support the existence of

regional variability in end-of-life practices.5 12 13

Hong Kong is a special administrative region of

China with an overwhelmingly Chinese population;

nevertheless, it maintains an independent fiscal

budget and healthcare system. The Hong Kong

Hospital Authority, funded by the Hong Kong SAR

Government, provides >90% of hospital-based

services available for the local population; although

nearly all healthcare workers in the public health

services exhibit Chinese ethnicity, health services

are based on Western medical conventions.14

Hong Kong is considered a high-income region,

and recently published patient outcomes data

indicate that the Hong Kong Hospital Authority

provides high-quality intensive care services.15 The

juxtaposition of a Western medical system and a

culturally Chinese population creates a situation

where Western medical practices (driven by Western

cultural and ethical values) may conflict with

Chinese cultural values, particularly at the end of

life when deep-rooted cultural beliefs may become

more relevant. A small number of studies have

explored end-of-life care practices in Hong Kong

ICUs; these include a survey of ICU physicians’

ethical attitudes concerning end-of-life care8 and a

prospective observational study regarding end-of-life

practices at a single tertiary university hospital.16

No observational territory-wide data have been

published thus far. Additionally, end-of-life practices

in Europe have substantially changed in recent

decades17; similar changes may have occurred in

Hong Kong, although previous comparative data

are sparse.16 Multiple Hong Kong ICUs participated

in the recent worldwide Ethicus-2 study,13 18 with

the understanding that the Hong Kong data would

be accessible for secondary analysis. The aim of

this study was to provide a detailed description of

current end-of-life care practices in Hong Kong.

Methods

This study constituted a secondary analysis of the

Ethicus-2 database, focusing on the Hong Kong data.

The Ethicus-2 study was a prospective, multicentre,

global observational study of end-of-life practices in

199 ICUs across 36 countries.13 17 All 15 adult ICUs in

publicly funded hospitals in Hong Kong were invited

to participate by the Hong Kong study coordinator,

representing the Hong Kong Society of Critical Care

Medicine. Eight ICUs in Hong Kong participated.

Consecutive adult patients admitted to the

ICU over an individual ICU-selected 6-month

period between 1 September 2015 and 30 September

2016 with LST limitation or death were included.

Follow-up continued until death or 2 months

from the initial decision to limit LST. End-of-life

categories included withholding LST, withdrawing

LST, active shortening of the dying process, failed cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and brain

death. These categories were mutually exclusive;

if more than one limitation was triggered in a

particular case, the most stringent limitation was

chosen (ie, active shortening of the dying process

was considered more stringent than LST withdrawal,

followed by LST withholding).

Data were collected by the senior physician, or

a representative, responsible for making end-of-life

decisions. De-identified patient data were entered

into a secure online database. Collected data included

age; sex; religion; end-of-life category; admission

date, time, and diagnoses; chronic disorders; use of

ventilation and vasopressors, sedatives, or analgesics;

date and time of hospital and ICU admission; and

date and time of death or discharge from the ICU or

hospital. End-of-life process data collected included

type, date, and time of LST; presence of information

about patient wishes; discussions with the patient

or their family; degree of concurrence between the

decision and patient/family wishes; and reasons for

treatment decisions.

Data quality was monitored by concurrent

audit and feedback, with a quality review involving

5% of all patients.17 Categorical variables were

reported as numbers and percentages within

end-of-life groups. After normality assessment

using the Shapiro–Wilk test, continuous variables

were reported as means (standard deviations)

or medians (interquartile ranges [IQRs]), as

appropriate. Differences among LST withholding,

LST withdrawal, and no LST limitation groups were

compared using analysis of variance, the Kruskal–Wallis H test, or the Chi squared test, as appropriate.

Subsequent pairwise group comparisons were

performed with Bonferroni correction for multiple

tests. All analyses were performed using SPSS

software (Windows version 27.0; IBM Corp, Armonk

[NY], United States).

This prospective observational study has been reported in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist for observational studies.

Results

The eight participating ICUs were distributed

across Hong Kong; at least two ICUs represented

each of the New Territories, Kowloon, and Hong

Kong Island. Two ICUs were located in academic

university hospitals (comprising 20 and 25 acute ICU

beds, respectively), and the remainder were located

in medium-to-large regional hospitals (ranging from

12 to 22 acute ICU beds per unit).

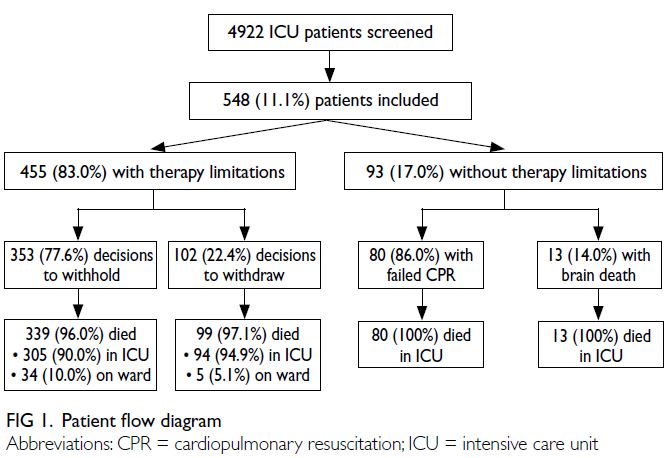

Among the 4922 consecutive patients screened

during the study period, 548 (11.1%) patients with

LST limitation (withholding or withdrawal) or death

(failed CPR or brain death) were included in the study. Life-sustaining treatment limitation occurred

in 455 (83.0%) patients, including 353 (77.6%) with

decisions to withhold LST and 102 (22.4%) with

decisions to withdraw LST. Of the 93 patients who

died without LST limitation, 80 (86.0%) had failed

CPR, and 13 (14.0%) experienced brain death (Fig 1). No patients underwent shortening of the dying process.

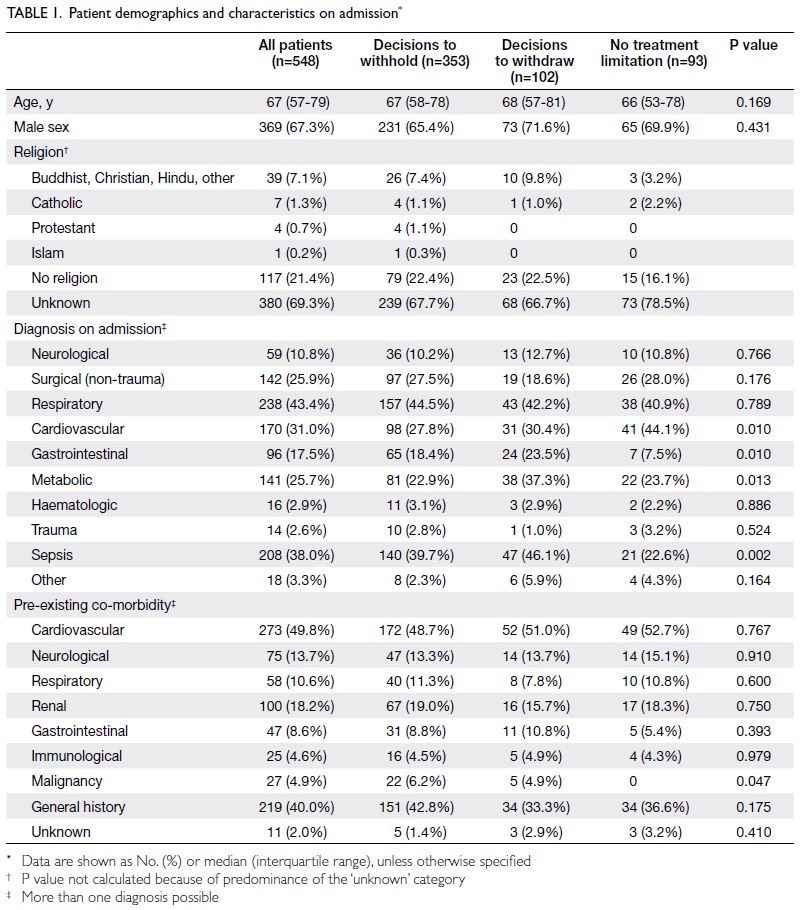

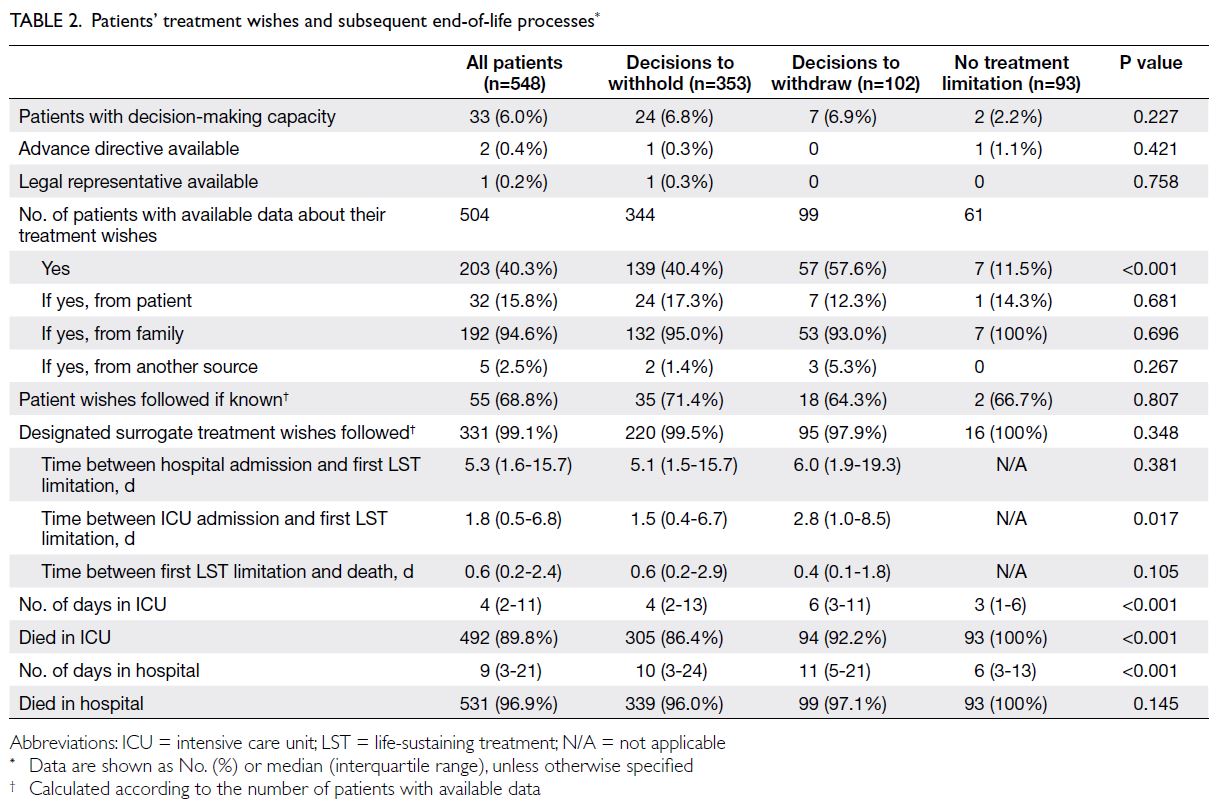

Patient characteristics are summarised in Table 1; knowledge of patient and family/surrogate wishes,

as well as the timing of end-of-life processes, are

described in Table 2. Patients without LST limitation

had a shorter duration of ICU stay (median: 3 days,

IQR=1-6) compared with patients who had decisions

to withhold (median: 4 days, IQR=2-13) or withdraw

(median: 6 days, IQR=3-11) [P<0.001].

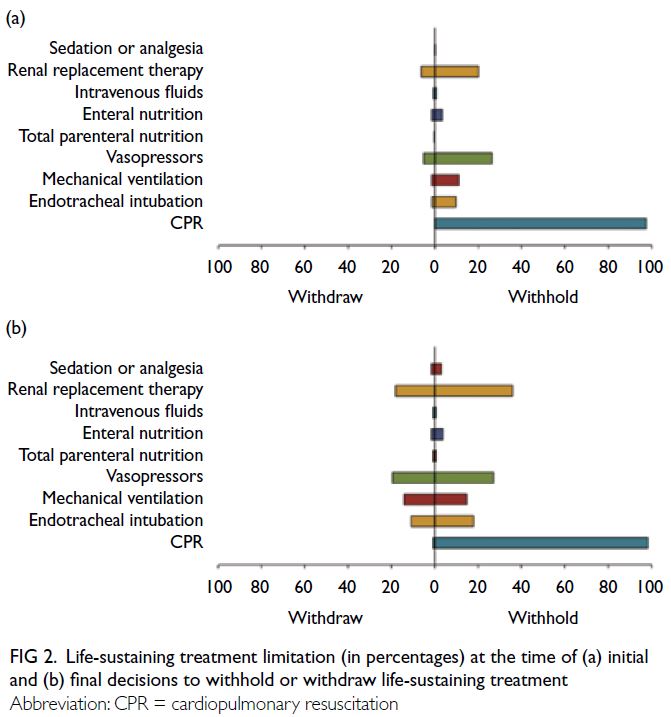

The prevalences of treatments withheld or

withdrawn at the initial and final decisions to limit

LST are shown in Figure 2. Higher percentages of

patients had endotracheal tube (P=0.009), renal

replacement therapy (P<0.001), and sedation/analgesia (P=0.002) withheld at the final decision,

compared with the initial decision. Similarly, higher

percentages of patients had endotracheal tube,

mechanical ventilation, vasopressor, and renal

replacement therapy withdrawn at the final decision

(all P<0.001), compared with the initial decision.

Figure 2. Life-sustaining treatment limitation (in percentages) at the time of (a) initial and (b) final decisions to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment

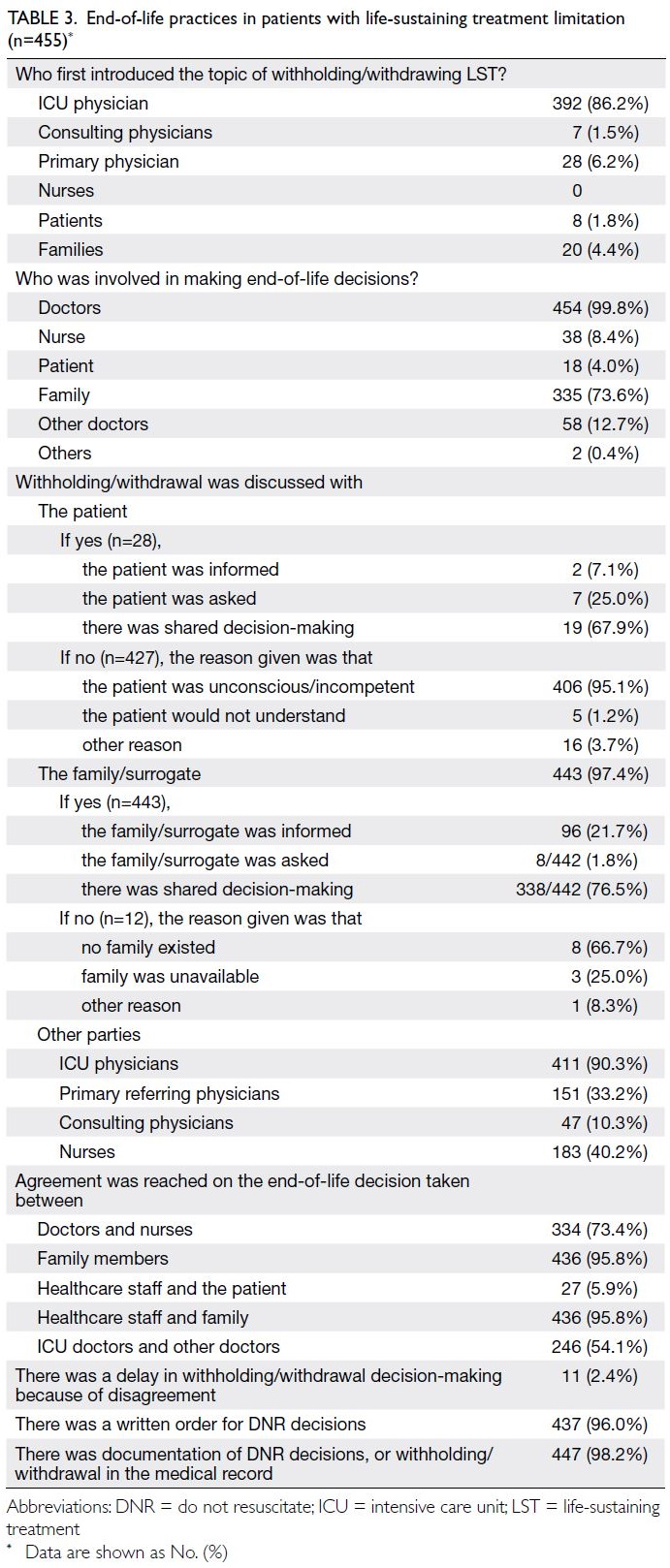

Information about decision-making practices

for patients with LST limitation is provided in Table 3. In the majority of cases, the ICU physician was

involved in key aspects of end-of-life decision-making

and implementation. The responsible

ICU physicians’ explanations of the reasons and

considerations for supporting end-of-life decisions

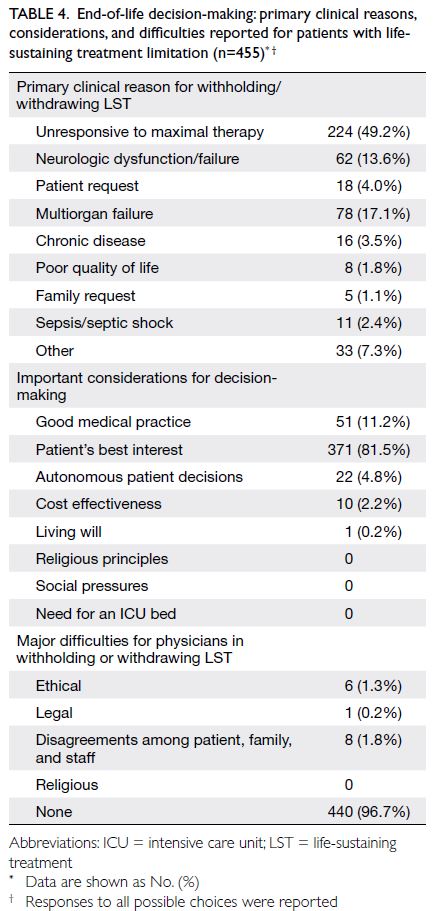

are provided in Table 4. The primary clinical reason

for limiting LST was unresponsiveness to maximal

therapy; the patient’s best interest, perceived good medical practice, and autonomy were key decision-making considerations.

Table 4. End-of-life decision-making: primary clinical reasons, considerations, and difficulties reported for patients with lifesustaining treatment limitation (n=455)

Discussion

This is the first large, multicentre, prospective,

observational study of end-of-life care practices in

Hong Kong ICUs. Our main findings were that LST

limitation preceded >80% of patient deaths, and

that death occurred in the vast majority of patients

with LST limitation; only 4% of patients with LST

limitation were alive at 2 months. Only 15% of

ICU patients died after failed CPR (ie, without any LST limitations). Advance directives were rarely

available, and no cases of active shortening of the

dying process (euthanasia) were reported. Life-sustaining

treatment limitation occurred in the

majority (83.0%) of patients, predominantly via

withholding (77.6%); withdrawal was less common

(22.4%) [Fig 1]. High rates of LST limitation, such as

those observed in this study, are generally presumed

to reflect good end-of-life practices and have been

associated with the presence of written end-of-life

guidelines,19 such as those provided by the Hong Kong Hospital Authority.20

Withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining

treatment

Regarding treatments that were withdrawn or

withheld, the withholding of CPR universally

accompanied all limitation decisions. Nutrition,

hydration, and sedation were rarely withheld or

withdrawn at any time, consistent with guidance from

professional bodies in Hong Kong that additional

safeguards are necessary when considering these

actions.20 At the time of the initial limitation

decision, there was relatively frequent withholding

of vasopressors and renal replacement therapy;

withholding or withdrawal of endotracheal tubes

was less common. Although the patterns of LST

limitation were similar between the initial and final

decisions, such that withholding remained more

prevalent than withdrawal, a substantial increase

was observed in the prevalence of LST withdrawal

at the time of the final decision. This finding may

reflect the common Chinese cultural perspective

that LST withholding and withdrawal are not

ethically equivalent, with a documented preference

for withholding over withdrawal as an end-of-life

care strategy.8 11 The increase in withdrawal

prevalence at the time of the final decision across key

treatment categories (eg, vasopressors, mechanical ventilation, and renal replacement therapy) suggests

that, with increasing prognostic certainty and clear

progression towards death, LST withdrawal becomes

more acceptable. There also appeared to be a greater

reluctance to adopt withdrawal strategies early in the

ICU stay, evidenced by the longer interval between

ICU admission and initial limitation, if the initial

limitation was withdrawal. This tendency may also

reflect the need for greater prognostic certainty

prior to the implementation of a withdrawal strategy.

Comparisons with international data indicate that

although the high rate of LST limitation prior to

death is similar to practices in other countries, the

early and more frequent use of withholding (rather

than withdrawal) remains distinct from practices reported in North America, North and Central Europe, and Asia.13

Comparative historical data from Hong

Kong are limited. A single-centre observational

study conducted between 1997 and 1999 showed

that LST limitation occurred in 59% of patients,16

although its LST limitation categories are not fully

aligned with those of the current study. Notably,

the mean interval between ICU admission and LST

limitation in this previous study was nearly 8 days,16

whereas the median interval in the current study

was 1.8 days (IQR=0.5-7); this difference suggests

that recognition of the need for LST limitation is

occurring much earlier in Hong Kong, consistent

with a pattern observed in Europe during the

same period.17 21 When LST limitation is indicated,

earlier intervention leads to a shorter duration of

patient discomfort; the observed reduction in time

to limitation may represent a meaningful practice

improvement over time.

Despite similar rates of LST withholding/withdrawal, the low rate of survival after LST

limitation in Hong Kong (3%-4%)—comparable to

the findings in a previous pan-European study12—contrasts with current European ICU outcomes,

where the combined survival rate after LST

withdrawal or withholding was 20%.17 This difference

may possibly be attributed to implementing LST

in patients at the very end-of-life when prognostic

certainty is greater. The earlier implementation of

end-of-life interventions may represent an area

for further exploration to improve end-of-life ICU

practices and minimise suffering.

Practice components of end-of-life care

Key practices in end-of-life decision-making

included the initiation of discussions to limit LST by

ICU physicians in the vast majority of cases; when

such discussions began, ICU physicians were always

involved in end-of-life decision-making processes.

Notably, shared decision-making between ICU

physicians and families was the predominant

model reported. These findings align with the best

practices described in recent international expert

consensus documents.1 3 Despite frequent use

of the shared decision-making model, direct or

indirect knowledge of the patient’s wishes regarding

LST was available for fewer than half of patients

(40.3%); in the vast majority of cases (94.6%), this

information was transmitted by relatives rather than

by the patient themselves. Only 33 (6.0%) patients

had decision-making capacity during the decision-making

process, and only two (0.4%) patients had

advance directives (Table 2). These results highlight

the need to encourage patients to discuss their

wishes regarding future end-of-life care preferences

with relatives, or communicate such wishes through

the use of advance directives, ensuring that patients receive the preferred level of care at this critical

time. Nevertheless, levels of agreement among all

parties regarding end-of-life decisions were high,

and delays in decision-making due to disagreement

were uncommon.

Advance directives

Advance directives in Hong Kong ICUs were rarely

available, possibly due to selection bias; individuals

with advanced disease and a greater likelihood of

advance directives may have lower ICU admission

priority. However, the current rate of advance

directive use in North American ICUs at the end of

life is nearly 50%.18 A relatively recent population-based

study demonstrated very low public awareness

of advance directives in Hong Kong, such that 86% of

participants reported no previous knowledge of the

advance directive concept.22 However, once informed

of this concept, the majority of participants indicated

a willingness to consider using such directives. The

legislative process to formalise advance directive

use in Hong Kong has substantially progressed,

and there is a recognised need for public education

and healthcare professional–specific guidance to

promote the use of these directives.23 24

Patient characteristics and reasons for limitations of life-sustaining treatment

In the present study, the most common diagnostic

categories at ICU admission were respiratory

(43.4%) and sepsis-related (38.0%) [Table 1],

similar to reported findings in most other regions

worldwide.18 There were no substantial age or sex

differences regarding LST limitation, but there were

distinct differences in ICU admission diagnoses,

such that limitation was less likely in patients

with cardiovascular conditions and more likely

in patients with sepsis or gastrointestinal disease.

The vast majority of patients exhibited at least one

co-morbidity, again similar to recently reported

findings in other regions.18 Intriguingly, no patients

with cancer were among those who died without

LST limitation.

The primary clinical reasons for initiating LST

limitation included unresponsiveness to maximal

therapy, multiorgan failure, and neurologic failure;

in few cases, the limitation arose from a family

request or mainly in relation to quality of life (Table 4). Overwhelmingly, the primary consideration for

decision-making was the patient’s best interest,

followed by the principle of good medical practice,

defined as the recognition that continued maximal

therapy would not be beneficial for the patient (Table 4). These observations closely match the responses

recently provided by a group of international experts

who were asked to rank the triggers they would likely

use in clinical practice to initiate discussions about

LST limitation.1

Decision-making at end-of-life

Two questions related to decision-making and

patient treatment wishes revealed an interesting

observation. Across all end-of-life categories,

approximately 70% of physicians in charge of end-of-life decision-making reported that if the patient’s

wishes were known, they were followed. In contrast,

when a surrogate’s treatment wishes were known,

they were followed in nearly every case (Table 2).

These responses indicate that the family’s treatment

preferences are respected more frequently compared

with known patient preferences, in contrast to

guidelines from the Medical Council of Hong Kong25 and the Hospital Authority.20 Both guidelines clearly

state that treatment preferences should be sought

via communication with patients and family when

possible, and a consensus should be reached; however,

when conflicting views cannot be reconciled, the

patient’s treatment preferences should supersede the

family’s preferences.20 25 It is possible that physicians

prioritised the family’s preferences because few

patients were capable of direct communication;

there was low certainty regarding perceived

patient wishes when communicated through third

parties. Nevertheless, this finding warrants further

investigation and reflection among Hong Kong ICU

healthcare professionals.

Most communication related to end-of-life

decision-making occurred between ICU physicians

and family/surrogates; nurses, primary physicians,

and consulting physicians were involved in

fewer than half of the reported cases. It has been

suggested that this relatively low percentage of nurse

involvement is an underestimate because most data

were reported by physicians who may be unaware of

nurse involvement.26 Decision agreement between

healthcare staff and family members, as well as

among family members, was reportedly very high

(>95%) [Table 3]. Disagreements between family

and staff were rare, as were delays in implementing

end-of-life care because of disagreement, indicating

a high level of acceptance of the decision-making

process by the public and healthcare professionals in

Hong Kong.

Strengths and limitations

This study’s strengths included its involvement of

a large number of patients over a 6-month period,

provision of detailed follow-up data for up to 2

months, prospective design, and representation of

most public ICUs in Hong Kong. Moreover, the data

were provided by the physician in charge of end-of-life decision-making, with support from clear

definitions and uniform collection across ICUs;

they were also subjected to external quality control

measures, minimising measurement bias. The main

limitations were the lack of random ICU allocation and inclusion of consenting ICUs only, which may have introduced selection bias.

Conclusion

Data from the majority of Hong Kong ICUs,

spanning the entire territory and representing both

academic and non-academic ICUs, revealed that LST

limitation occurs in most patients prior to death in

ICU. Practices generally align with recommendations

from local professional bodies and key international

consensus documents. Although decision-making

is usually initiated by ICU physicians, shared

decision-making between medical staff and family/surrogates is the predominant model. Because a loss

of decision-making capacity is common in the ICU,

patients should be encouraged to communicate their

wishes regarding end-of-life care through dialogue

with relatives or more formal methods. Certain

practices and outcomes observed in Hong Kong are

more similar to those reported in North America

and Europe than to patterns in other parts of Asia.

Author contributions

Concept or design: CL Sprung, A Avidan, GM Joynt.

Acquisition of data: GM Joynt, SKH Ling, LL Chang, PNW Tsai, GKF Au, DHK So, FL Chow, PKN Lam.

Analysis or interpretation of data: A Lee, GM Joynt.

Drafting of the manuscript: GM Joynt.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: GM Joynt, SKH Ling, LL Chang, PNW Tsai, GKF Au, DHK So, FL Chow, PKN Lam.

Analysis or interpretation of data: A Lee, GM Joynt.

Drafting of the manuscript: GM Joynt.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

No funding was obtained to conduct this research from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit

sectors. The Walter F and Alice Gorham Foundation funded

the international co-ordination of the Ethicus-2 study. The

Foundation had no part in the design and conduct of the

research; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation

of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript;

and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the relevant Research Ethics Committee for each of the participating centres, including:

(1) Tuen Mun Hospital—The New Territories West Cluster Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: NTWC/CREC/15078);

(2) Prince of Wales Hospital and North District Hospital—The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong—New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee, Hong Kong (Ref No.: 2015.080);

(3) Caritas Medical Centre—The Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Authority, Hong Kong [Ref No.: KW/EX-15-103(88-02)];

(4) Kwong Wah Hospital—The Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Authority, Hong Kong [Ref No.: KW/EX-15-105(88-04)];

(5) Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital—The Hong Kong East Cluster Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: HKEC-2015-028);

(6) Princess Margaret Hospital—The Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Authority, Hong Kong [Ref No.: KW/EX-15-104(88-03)]; and

(7) Queen Mary Hospital—Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong / Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster, Hong Kong (Ref No.: UW 15-361).

(1) Tuen Mun Hospital—The New Territories West Cluster Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: NTWC/CREC/15078);

(2) Prince of Wales Hospital and North District Hospital—The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong—New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee, Hong Kong (Ref No.: 2015.080);

(3) Caritas Medical Centre—The Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Authority, Hong Kong [Ref No.: KW/EX-15-103(88-02)];

(4) Kwong Wah Hospital—The Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Authority, Hong Kong [Ref No.: KW/EX-15-105(88-04)];

(5) Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital—The Hong Kong East Cluster Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: HKEC-2015-028);

(6) Princess Margaret Hospital—The Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Authority, Hong Kong [Ref No.: KW/EX-15-104(88-03)]; and

(7) Queen Mary Hospital—Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong / Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster, Hong Kong (Ref No.: UW 15-361).

The requirement for informed patient consent was waived

by the relevant Clinical Research Ethics Committees as the

study was observational only, where all collected data were

anonymised at source and only de-identified data were

passed on to the co-ordinating centre for analysis, and risk to

participants was minimal.

Members of the Hong Kong Ethicus-2 study

group (in alphabetical order):

Gary KF Au, Department of Intensive Care, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Alexander Avidan, Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Hadassah Medical Organization and Faculty of Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

KC Chan, Department of Intensive Care, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

WM Chan, Adult Intensive Care Unit, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

LL Chang, Department of Intensive Care, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

FL Chow, Department of Intensive Care, Caritas Medical Centre, Hong Kong SAR, China

Gavin Matthew Joynt, Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Gladys WM Kwan, Department of Intensive Care, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Philip KN Lam, Department of Intensive Care, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Anna Lee, Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

E Leung, Adult Intensive Care Unit, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Steven KH Ling, Department of Intensive Care, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

CH Ng, Department of Intensive Care, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

HP Shum, Department of Intensive Care, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Dominic HK So, Department of Intensive Care Unit, Princess Margaret Hospital/Yan Chai Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Charles L Sprung, Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Hadassah Medical Organization and Faculty of Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

L Sy, Department of Intensive Care, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Polly NW Tsai, Adult Intensive Care Unit, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

HH Tsang, Department of Intensive Care, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

WT Wong, Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Alexander Avidan, Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Hadassah Medical Organization and Faculty of Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

KC Chan, Department of Intensive Care, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

WM Chan, Adult Intensive Care Unit, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

LL Chang, Department of Intensive Care, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

FL Chow, Department of Intensive Care, Caritas Medical Centre, Hong Kong SAR, China

Gavin Matthew Joynt, Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Gladys WM Kwan, Department of Intensive Care, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Philip KN Lam, Department of Intensive Care, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Anna Lee, Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

E Leung, Adult Intensive Care Unit, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Steven KH Ling, Department of Intensive Care, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

CH Ng, Department of Intensive Care, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

HP Shum, Department of Intensive Care, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Dominic HK So, Department of Intensive Care Unit, Princess Margaret Hospital/Yan Chai Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Charles L Sprung, Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Hadassah Medical Organization and Faculty of Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

L Sy, Department of Intensive Care, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Polly NW Tsai, Adult Intensive Care Unit, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

HH Tsang, Department of Intensive Care, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

WT Wong, Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

References

1. Joynt GM, Lipman J, Hartog C, et al. The Durban World

Congress Ethics Round Table IV: health care professional

end-of-life decision making. J Crit Care 2015;30:224-30. Crossref

2. Vincent JL. Forgoing life support in western European

intensive care units: the results of an ethical questionnaire.

Crit Care Med 1999;27:1626-33. Crossref

3. Sprung CL, Truog RD, Curtis JR, et al. Seeking worldwide

professional consensus on the principles of end-of-life

care for the critically ill. The Consensus for Worldwide

End-of-Life Practice for Patients in Intensive Care

Units (WELPICUS) study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2014;190:855-66. Crossref

4. Phua J, Joynt GM, Nishimura M, et al. Withholding and

withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in low-middle-income

versus high-income Asian countries and regions.

Intensive Care Med 2016;42:1118-27. Crossref

5. Lobo SM, De Simoni FH, Jakob SM, et al. Decision-making

on withholding or withdrawing life support in the ICU: a

worldwide perspective. Chest 2017;152:321-9. Crossref

6. Wong WT, Phua J, Joynt GM. Worldwide end-of-life

practice for patients in ICUs. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol

2018;31:172-8. Crossref

7. Attitudes of critical care medicine professionals concerning

forgoing life-sustaining treatments. The Society of Critical

Care Medicine Ethics Committee [editorial]. Crit Care

Med 1992;20:320-6. Crossref

8. Yap HY, Joynt GM, Gomersall CD. Ethical attitudes of

intensive care physicians in Hong Kong: questionnaire

survey. Hong Kong Med J 2004;10:244-50.

9. Yaguchi A, Truog RD, Curtis JR, et al. International differences in end-of-life attitudes in the intensive care unit: results of a survey. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1970-5. Crossref

10. Bito S, Asai A. Attitudes and behaviors of Japanese

physicians concerning withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining

treatment for end-of-life patients: results from

an Internet survey. BMC Med Ethics 2007;8:7. Crossref

11. Weng L, Joynt GM, Lee A, et al. Attitudes towards ethical

problems in critical care medicine: the Chinese perspective.

Intensive Care Med 2011;37:655-64. Crossref

12. Sprung CL, Cohen SL, Sjokvist P, et al. End-of-life practices

in European intensive care units: the Ethicus study. JAMA

2003;290:790-7. Crossref

13. Avidan A, Sprung CL, Schefold JC, et al. Variations in end-of-life practices in intensive care units worldwide (Ethicus-2): a prospective observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:1101-10. Crossref

14. Kong X, Yang Y, Gao J, et al. Overview of the health care

system in Hong Kong and its referential significance to

mainland China. J Chin Med Assoc 2015;78:569-73. Crossref

15. Ling L, Ho CM, Ng PY, et al. Characteristics and outcomes

of patients admitted to adult intensive care units in Hong

Kong: a population retrospective cohort study from 2008 to 2018. J Intensive Care 2021;9:2. Crossref

16. Buckley TA, Joynt GM, Tan PY, Cheng CA, Yap FH.

Limitation of life support: frequency and practice in a Hong

Kong intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2004;32:415-20. Crossref

17. Sprung CL, Ricou B, Hartog CS, et al. Changes in end-of-life

practices in European intensive care units from 1999 to

2016. JAMA 2019;322:1692-704. Crossref

18. Feldman C, Sprung CL, Mentzelopoulos SD, et al. Global

comparison of communication of end-of-life decisions in

the ICU. Chest 2022;162:1074-85. Crossref

19. Mentzelopoulos SD, Chen S, Nates JL, et al. Derivation

and performance of an end-of-life practice score aimed at

interpreting worldwide treatment-limiting decisions in the

critically ill. Crit Care 2022;26:106. Crossref

20. Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government. Working

Group on review of Hospital Authority Clinical Ethics

Committee (HKCEC) guidelines related to EOL decisionmaking.

HA Guidelines on Life-Sustaining Treatment

in the Terminally Ill. 2020. Available from: https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/psrm/LSTEng.pdf. Accessed 4 Jul 2023.

21. Lesieur O, Herbland A, Cabasson S, Hoppe MA, Guillaume F,

Leloup M. Changes in limitations of life-sustaining

treatments over time in a French intensive care unit: a

prospective observational study. J Crit Care 2018;47:21-9. Crossref

22. Chung RY, Wong EL, Kiang N, et al. Knowledge, attitudes,

and preferences of advance decisions, end-of-life care, and

place of care and death in Hong Kong. A population-based

telephone survey of 1067 adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc

2017;18:367.e19-27. Crossref

23. Food and Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government.

End-of-Life Care: Legislative Proposals on Advance

Directives and Dying in Place Consultation Report. July

2020. Available from: https://www.healthbureau.gov.hk/download/press_and_publications/consultation/190900_eolcare/e_EOL_consultation_report.pdf . Accessed 4 Jul 2023.

24. Fong BY, Yee HH, Ng TK. Advance directives in Hong Kong: moving forward to legislation. Ann Palliat Med 2022;11:2622-30. Crossref

25. Medical Council of Hong Kong. Code of professional

conduct: for the guidance of registered medical

practitioners. Revised October 2022. Available from:

https://www.mchk.org.hk/english/code/files/Code_of_Professional_Conduct_(English_Version)_(Revised_in_October_2022).pdf . Accessed 4 Jul 2023.

26. Benbenishty J, Ganz FD, Anstey MH, et al. Changes in

intensive care unit nurse involvement in end of life decision

making between 1999 and 2016: descriptive comparative

study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2022;68:103138. Crossref