MEDICAL PRACTICE

Recommendations for eligibility criteria concerning bariatric and metabolic surgical and endoscopic procedures for obese Hong Kong adults 2024: Hong Kong Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Position Statement

Shirley YW Liu, FRCS, FHKAM (Surgery)1; Carol MS Lai, FRCS, FHKAM (Surgery)1; Enders KW Ng, FRCS, FHKAM (Surgery)1; Fion SY Chan, FRCS, FHKAM (Surgery)2; SK Leung, FRCS, FHKAM (Surgery)3; Wilfred LM Mui, FRCS, FHKAM (Surgery)4; Daniel KH Tong, FRACS, FHKAM (Surgery)5; Dennis CT Wong, FRACS, FHKAM (Surgery)6; Patricia PC Yam, FRCS, FHKAM (Surgery)3; Simon KH Wong, FRCS, FHKAM (Surgery)1

1 Department of Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Surgery, Queen Mary Hospital, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Surgery, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Hong Kong Bariatric and Metabolic Institute, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

6 St Teresa's Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Full paper in PDF

Full paper in PDF

Abstract

The surgical management of obesity in Hong

Kong has rapidly evolved over the past 20 years.

Despite increasing public awareness and demand

concerning bariatric and metabolic surgery, service

models generally are not standardised across

bariatric practitioners. Therefore, a working group

was commissioned by the Hong Kong Society for

Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery to review relevant

literature and provide recommendations concerning

eligibility criteria for bariatric and metabolic

interventions within the local population in Hong

Kong. The current position statement aims to provide

updated guidance regarding the indications and

contraindications for bariatric surgery, metabolic

surgery, and bariatric endoscopic procedures.

Obesity is a complex multifactorial disease caused

by diverse combinations of genetic, behavioural,

environmental, and endocrine aetiologies. In 2013,

obesity was recognised by the American Medical

Association as a disease state requiring treatment and

prevention efforts.

1 Obesity substantially increases

an individual’s risks of cardiovascular diseases,

metabolic illnesses, musculoskeletal problems, and

cancer. For healthcare policymakers, the financial

burden of treating and preventing obesity and its

related conditions is exponentially growing. At the

community level, reduced workforce productivity

from obesity-related adverse health outcomes can

lead to detrimental impacts on the broader economy.

According to the World Health Organization,

adults are considered overweight when their body

mass index (BMI) is ≥25 kg/m

2 and obese when their

BMI is ≥30 kg/m

2.

2 However, Asian populations have

a higher percentage of body fat and greater metabolic

risk at lower BMIs.

3 A World Health Organization

expert consultation identified potential public health

action points for Asians as 23.0 kg/m

2, 27.5 kg/m

2, 32.5 kg/m

2, and 37.5 kg/m

2; these values generally

were 2.5 kg/m

2 lower than the thresholds established

for Caucasians.

4 Because of differences in body frame

and visceral fat distribution, lower BMI thresholds

were used to define overweight (≥23 kg/m

2) and

obesity (≥25 kg/m

2) in Asians.

3

Similar to other regions of the world, obesity

is a substantial public health problem in Hong

Kong.

5 According to the latest Population Health Survey 2020/22 conducted by the Department of

Health, the prevalences of obesity and overweight in

people aged 15 to 84 years were 32.6% and 22.0%,

respectively.

6 These prevalences indicate that at least

half of the local Hong Kong population faces health

risks associated with overweight or obesity.

Bariatric and metabolic surgery

Bariatric surgery (ie, surgical treatment for obesity)

has been continuously evolving worldwide over the

past 50 years, with increasingly diverse procedural

options and indications.

7 In 1991, the National Institutes of Health published the first international

consensus endorsing the use of gastrointestinal

surgery as treatment for severe obesity.

8 9 Since then,

numerous studies have confirmed the effectiveness

of bariatric surgery in achieving sustainable weight

loss and substantial improvement in co-morbidities

among obese patients.

10 According to a systematic

review and meta-analysis of 22 094 morbidly

obese patients across 136 studies, bariatric surgery

resulted in 61.2% excess weight loss.

10 Resolution

of diabetes, hypertension, and obstructive sleep

apnoea were achieved in 76.8%, 61.7%, and 85.7% of

patients, respectively.

10 In a prospective randomised

trial of 150 morbidly obese diabetic patients,

bariatric surgery plus intensive medical therapy

was associated with significantly better glycaemic

and metabolic outcomes at 5 years compared with

intensive medical therapy alone.

11 Because bariatric

surgery has demonstrated efficacy in treating type

2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), the term ‘metabolic

surgery’ was established to describe the role of

bariatric interventions in treating T2DM and

metabolic syndrome.

7 16 In 2016, metabolic surgery

was formally endorsed by 44 international diabetes

organisations as a treatment option for adults with

T2DM and obesity (defined as BMI >30 kg/m

2 for

Caucasians and >27.5 kg/m

2 for Asians), particularly

those with co-morbidities which cannot be

controlled by lifestyle changes and pharmacological

therapy.

17

Although operative safety is a concern for

morbidly obese individuals undergoing any type

of major surgery, current evidence suggests that

bariatric surgery has low perioperative mortality

rates, ranging from 0.03% to 0.2%.

12 In a systematic

review and meta-analysis of 161 756 patients

undergoing bariatric surgery, the 30-day mortality

rates ranged from 0.08% to 0.22%, whereas the

postoperative complication rates were between 9.8%

and 17.0%.

13 Currently, the most widely performed bariatric procedures are sleeve gastrectomy and

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Common operative

morbidities of sleeve gastrectomy include bleeding,

leakage, stricture, and symptoms of gastroesophageal

reflux.

14 Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is associated with

bleeding, leakage, stricture, stomal ulcer, small

bowel obstruction, internal herniation, and dumping

syndrome.

15 Data from randomised controlled trials

suggest that sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y

gastric bypass are comparable in terms of 30-day

mortality and morbidity rates.15

Primary bariatric endoscopic intervention

In recent decades, bariatric endoscopic procedures

have been developed for individuals who prefer

less invasive, non-surgical alternatives.

18 These

endoscopic therapies include intragastric space-occupying

devices (intragastric balloons [IGBs]),

gastric aspiration devices, endoluminal bypass

barrier sleeves, the POSE (primary obesity

surgery endoluminal) procedure, endoscopic

sleeve gastroplasty, and duodenal mucosal

resurfacing. All of these procedures can produce

clinically significant short-term weight loss and

improvements in obesity-related co-morbidities.

19

The first bariatric endoscopic intervention in Hong

Kong, IGB therapy, was introduced in 2004. An

early local report confirmed its efficacy in weight

reduction and co-morbidity improvement among

obese patients at 6 months after treatment.

20

Compared with weight-reduction medication, IGB

therapy was associated with better compliance and

superior weight reduction for up to 2 years after

treatment.

21 Because of its efficacy regarding short-term

weight loss and co-morbidity improvement,

IGB therapy can also serve as a bridging treatment

prior to bariatric or other operative interventions; it

facilitates preoperative weight loss that can reduce

anaesthetic risks. Thus, IGB therapy is a justifiable

non-surgical bariatric option for primary weight loss

and preoperative weight loss.

Overview of bariatric and metabolic surgery in Hong Kong

Hong Kong’s first bariatric surgery programme was

established in 2002 at Prince of Wales Hospital,

affiliated with The Chinese University of Hong

Kong.

22 Encouraged by the success and safety of

the early Prince of Wales Hospital obesity surgery

service,

23 increasing numbers of public and private

hospitals have begun to provide bariatric surgical

interventions to obese patients in Hong Kong (

Table).

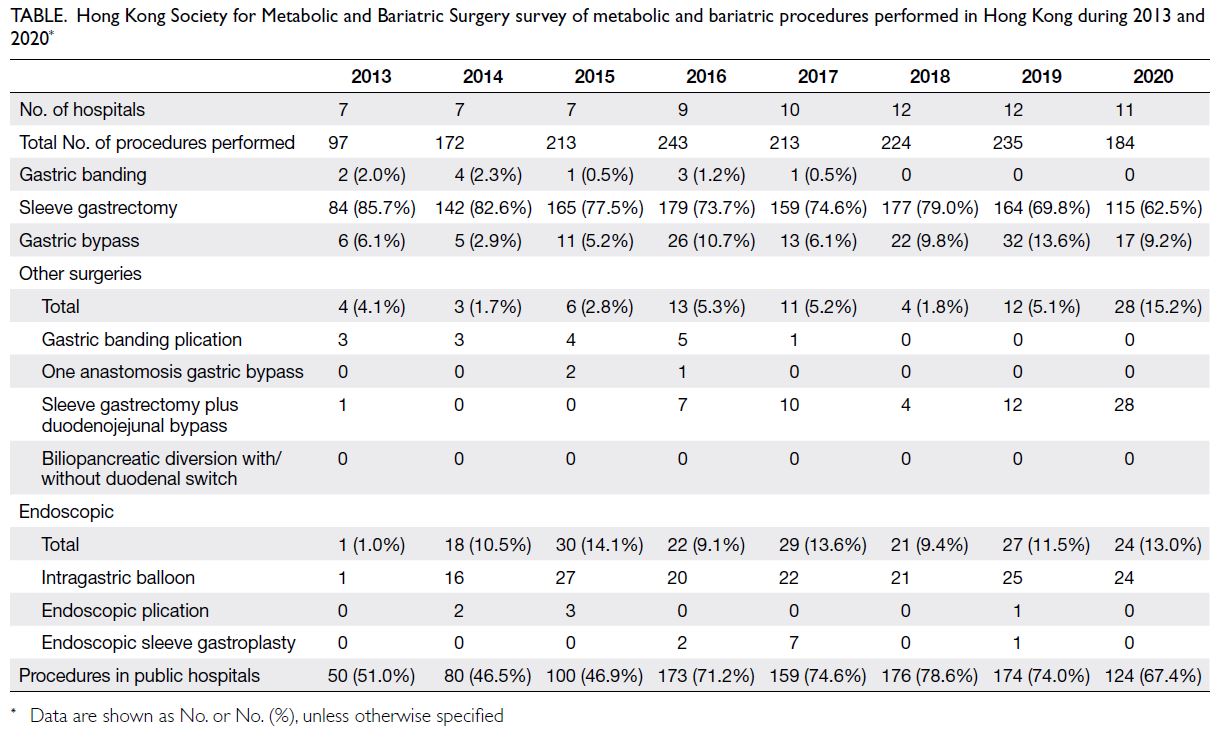

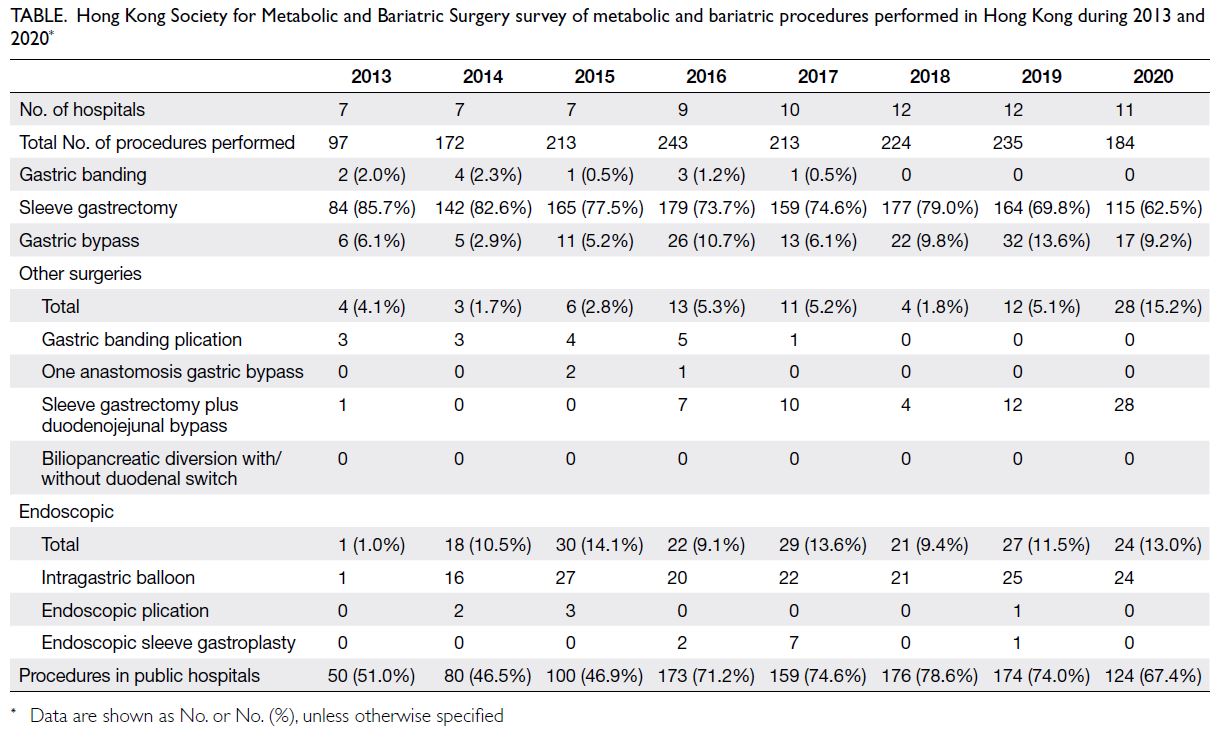

Table.

Table. Hong Kong Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery survey of metabolic and bariatric procedures performed in Hong Kong during 2013 and 2020

With the goal of promoting public and

professional awareness about obesity treatment,

leading local bariatric practitioners formed the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Group under the

Hong Kong Association for the Study of Obesity in

2012. In 2017, the Hong Kong Society for Metabolic

and Bariatric Surgery (HKSMBS) was established

as an independent society. Surveys concerning

bariatric surgery types and case volumes are carried

out annually by the two bodies.

Metabolic and bariatric surgery options are

broadly classified as restrictive procedures and

malabsorptive procedures. In Hong Kong, common

restrictive procedures are gastric banding and sleeve

gastrectomy. The most common malabsorptive

procedure is Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Other

less common malabsorptive procedures are one

anastomosis gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy

plus duodenojejunal bypass, and biliopancreatic

diversion with or without duodenal switch.

Between 2013 and 2020, 1582 bariatric surgical and

endoscopic procedures were performed in Hong

Kong (Table). Compared with 2002 when bariatric

surgery was first introduced, the number of bariatric

surgeries performed each year has exponentially

increased from <10 cases per year to >180 cases

per year in 2020. Current data indicate that more

than two-thirds of these surgeries are performed

in government hospitals. Sleeve gastrectomy is the most common bariatric procedure in Hong Kong

(~70%) and the second most common procedure is

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Gastric banding, popular

two decades ago, has not been favoured since 2013

(<2.5%). Biliopancreatic diversion with or without

duodenal switch has not been performed in Hong

Kong in the past ten years (

Table).

Development of the position statement

Although extensive international guidelines for

bariatric surgery have been established by various

bariatric authorities,

24 25 26 27 some of the existing

recommendations are not applicable to the Hong

Kong Chinese population because of ethnic and

practical differences. Nevertheless, there is a

lack of practical guidelines regarding bariatric

endoscopic interventions for Asian populations.

28

Among local bariatric practitioners, there has

been a lack of consensus regarding the indications,

contraindications, and procedural options for

bariatric surgery. This heterogeneity in clinical

practices surrounding bariatric surgery in Hong

Kong requires a position statement to address the

concerns of local bariatric practitioners.

In 1991, the National Institutes of Health

published a consensus statement regarding

indications for bariatric surgery; it utilised BMI

thresholds of ≥40 kg/m

2 or ≥35 kg/m

2 with co-morbidities

for Caucasians.

9 The American

Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and

International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity

and Metabolic Disorders recently updated the

indications for metabolic and bariatric surgery.

29

Their joint statement suggested a new threshold

of ≥35 kg/m

2 to receive a recommendation for

metabolic or bariatric surgery, regardless of the

presence, absence, or severity of co-morbidities.

Additionally, metabolic and bariatric surgery should

be considered for individuals with metabolic disease

and BMI ≥30 kg/m

2. For Asian populations, the joint

statement suggested that BMI thresholds should

be adjusted; specifically, individuals with BMI

>27.5 kg/m

2 should be offered metabolic and

bariatric surgery options.

29 In response to these

revised BMI thresholds for metabolic and bariatric

surgery, published in December 2022, extensive

discussions and debates have arisen in various

professional bodies focusing on metabolic and

bariatric surgery in Asia, including groups in

Hong Kong. Due to limited experience offering

metabolic and bariatric surgery to patients with BMI

<30 kg/m

2 in Hong Kong and other parts of Asia,

long-term surgical risks and benefits for such

patients have not been fully elucidated. Considering

that metabolic and bariatric surgery options are

associated with higher risks of perioperative

morbidity in patients with lower BMI, the HKSMBS

has reached a consensus to refrain from adopting

the newly updated BMI threshold of ≥27.5 kg/m

2

to receive a recommendation for metabolic and

bariatric surgery in this position statement.

The following position statement is issued

by the HKSMBS to define the indications and

contraindications for bariatric procedures and

endoscopic interventions which are suitable for the

Hong Kong population. The recommendations of

this position statement are based on current clinical

knowledge, expert opinion, and published peer-reviewed

scientific evidence.

25 26 27 28

General recommendations

The HKSMBS recommends that bariatric and

metabolic surgery be performed by surgeons

with specialised experience and training in these

procedures. Additionally, such procedures should be

conducted at facilities with multidisciplinary teams

of experts for appropriate perioperative assessment

and follow-up care. The multidisciplinary team may

include experienced surgeons, internal medicine

physicians, weight management coordinators,

nutritionists, exercise physiologists, and

psychologists or mental health professionals.

Eligibility for bariatric surgery

We define bariatric surgery as any surgical

procedure primarily intended for weight reduction

to improve physical and mental health in patients

with severe obesity. After careful review of available

data concerning the safety and efficacy of surgery

for obesity and weight-related diseases, as well as

the effectiveness of such surgery as treatment for

obesity and related co-morbidities, the position

statement committee reached a consensus on

the recommendation of bariatric surgery for the

following eligible candidates in the Hong Kong

adult population (aged ≥18 years) who are unable to

sustain weight loss through optimal lifestyle, dietary

or non-surgical interventions:

30

- appropriate surgical candidates who have a BMI

≥35 kg/m2 with or without obesity-related co-morbidities;

and

- appropriate surgical candidates who have a BMI

≥30 kg/m2 with clinically significant obesity-related

co-morbidities.

We define obesity-related co-morbidities as

conditions either directly caused by obesity or known

to contribute to the presence or severity of obesity.

These comorbid conditions are expected to improve

or resolve with effective and sustained weight loss.

The list of comorbid conditions includes, but is

not limited to, metabolic syndrome,31 T2DM, non-alcoholic

steatohepatitis, obstructive sleep apnoea

syndrome, degenerative arthritis, and polycystic

ovarian syndrome.

Eligibility for metabolic surgery

We define metabolic surgery as any surgical

procedure primarily intended to improve glycaemic

control in obese patients with T2DM. For adults (aged

≥18 years) with T2DM who are unable to sustain

weight loss through optimal lifestyle interventions,

metabolic surgery is recommended for the following

eligible candidates in treating T2DM with the

primary aim of glycaemic improvement:

17

- appropriate surgical candidates with BMI ≥37.5

kg/m2, regardless of the level of glycaemic control

or complexity of glucose-lowering regimens; and

- appropriate surgical candidates with BMI ranging

from 32.5 to 37.4 kg/m2 whose hyperglycaemia

is inadequately controlled by optimal medical,

lifestyle, dietary, and non-surgical interventions.

In addition, metabolic surgery can be regarded

as a treatment option for T2DM in appropriate

surgical candidates with BMI ranging from 27.5 to

32.4 kg/m2 whose hyperglycaemia is inadequately

controlled despite optimal medical control by either

oral or injectable medications (including insulin)

and lifestyle interventions.

We consider hyperglycaemia to be inadequately

controlled if the glycated haemoglobin level is >7.0% despite medical treatment involving two or

more oral hypoglycaemic agents or any injectable

medications (including insulin or glucagon-like

peptide-1 receptor agonist) for >6 months.

32 33

Fasting C-peptide levels should be checked if type 1

diabetes mellitus or latent autoimmune diabetes in

adults is suspected.

Eligibility for bariatric endoscopic

interventions

Intragastric balloon therapy

Intragastric balloon therapy is a minimally invasive

space-occupying system intended to provide

temporary weight loss by reducing gastric volume

and altering gastric motility.

34 35 The following

recommendations regarding IGB therapy are suggested:

1. As a bridging treatment for preoperative weight

loss, IGB therapy can be considered:

a. prior to metabolic or bariatric surgery for the optimisation of medical and/or anaesthetic status in severely obese individuals with very high BMI (eg, >50 kg/m2) who fail to respond to non-surgical optimisation; and

b. prior to non-bariatric surgery (eg, joint replacement surgery, ventral hernia repair, etc) for the optimisation of medical and/or anaesthetic status in obese individuals with BMI >30 kg/m2.

2. As a primary interventional treatment, IGB therapy can be considered:

a. in individuals with BMI ranging from 27.5 to 32.5 kg/m2 (30-35 kg/m2 for Caucasians) who fail to achieve weight loss through optimal lifestyle and dietary interventions; and

b. in obese individuals who meet the eligibility criteria for bariatric or metabolic surgery but are surgically unfit or reluctant to undergo bariatric or metabolic surgery.

3. Intragastric balloon therapy should be used for a

duration shorter than the maximum approved or

recommended duration (usually 4 to 12 months,

depending on IGB brand), or for a duration to be

decided on a case-by-case basis. Patients should

be informed about the intended duration of use.

Other endoscopic procedures

Currently, many restrictive and malabsorptive endoscopic procedures are available. These include,

but are not limited to, the following:

- space-occupying restrictive gastric devices (eg,

TransPyloric Shuttle, SatiSphere, Plenity, etc);

- gastric diversion devices (eg, AspireAssist

aspiration therapy);

- endoscopic gastric plication techniques (eg,

endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty, the POSE

procedure); and

- malabsorptive techniques (eg, duodenojejunal

bypass liner).

Some of these procedures have been approved

by the United States Food and Drug Administration,

whereas others remain investigational in most

countries. Except for endoscopic gastric plication,

AspireAssist aspiration therapy and endoscopic

sleeve gastroplasty, most of these endoscopic

procedures have not been explored in Hong Kong.

Due to the lack of scientific evidence and universal

consensus regarding their indications, efficacy, and

safety, these procedures should only be conducted

after careful evaluation and the acquisition of

informed patient consent and/or approval from

institutional review board.

Contraindications

Despite the beneficial effects of metabolic and

bariatric surgery with clinically significant

improvements in obesity-related co-morbidities,

these procedures are not without surgical and

anaesthetic risks. Moreover, most bariatric

procedures involve a gastric restrictive component;

an individual’s ability to maintain postoperative

dietary and lifestyle changes can substantially affect

surgical outcomes. Therefore, the position statement

committee reached a consensus on the following

suggestions.

Contraindications for bariatric and metabolic surgical and endoscopic interventions

Bariatric and metabolic surgical and endoscopic

procedures should not be performed in the following

situations or for the following individuals:

1. absence of multidisciplinary medical, dietary,

and behavioural guidance;

2. no fully informed consent from the patient or his/

her guardian regarding the risks, benefits, and

real expectations for weight loss, co-morbidity

management, and durability;

3. individuals with BMI <27.5 kg/m

2 (<30 kg/m

2

for Caucasians), unless the procedures are

performed under a research protocol approved

by a local institutional review board and/or

research ethics committee and informed patient

consent has been obtained;

4. individuals with medical conditions which

cannot be optimised before surgery, leading to

significantly increased anaesthetic and operative

risks. These conditions include, but are not

limited to, the following:

a. very high anaesthetic risk (defined as grade IV under the classification system of the American Society of Anesthesiologists) with organ failure that cannot be optimised and represents a constant threat to life;

b. uncontrolled endocrine disorders (eg, hypothyroidism, Cushing’s syndrome, drug-induced obesity, etc);

c. active infection (eg, tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus, etc);

d. uncorrected coagulopathy;

e. end-stage liver cirrhosis with or without portal venous hypertension;

f. uncontrolled enteropathy (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, protein-losing enteropathy, etc);

g. disseminated malignancy or advanced malignancy with <5 years of remission; and

h. uncontrolled major organ dysfunction (eg, cardiac, pulmonary, or renal disorders);

5. individuals with conditions that impair their

understanding of surgery and preclude them

from maintaining perioperative lifestyle changes.

These conditions include, but are not limited to,

the following:

a. inadequately controlled psychiatric illnesses (eg, untreated schizophrenia, major depression, bipolar affective disorder, eating disorders, etc);

b. major depression with suicidal ideation and/or attempt within the past year;

c. personality disorder involving poor compliance with instructions; and

d. active substance abuse/alcoholism;

6. individuals with potential non-compliance

problems regarding perioperative dietary and

lifestyle changes. These conditions include, but

are not limited to, the following:

a. intellectual/mental disability;

b. syndromic/genetic disease leading to obesity;

c. condition causing immobility (eg, paraplegia, stroke, etc); and

d. inability to attend regular follow-up.

Moreover, bariatric and metabolic surgical

and endoscopic procedures should not be offered to

pregnant women.

Contraindications specific to intragastric

balloon therapy

Generally, individuals with the above

contraindications for bariatric and metabolic

surgical interventions are also not recommended

to undergo IGB therapy. However, there are

additional contraindications for IGB therapy. These

contraindications include, but are not limited to, the

following, where IGB therapy is not recommended

for individuals:

- with contraindications for endoscopies, allergies

to proton-pump inhibitors, or allergies to balloon

materials (eg, silicone, polyurethane, etc);

- with active gastrointestinal pathology (eg, peptic

ulcers, gastroesophageal varices, inflammatory

bowel disease, etc), altered gastrointestinal

anatomy (eg, previous gastrointestinal surgery,

large hernia, suspect gastrointestinal malignancy, etc), gastrointestinal motility disorders, or a

history of idiopathic acute pancreatitis; and

- actively using anticoagulants or antiplatelet

medications, or individuals with a bleeding

tendency.

For patients who are intended to undergo

swallowable IGB therapy without prior endoscopy,

a preoperative endoscopic examination should be

considered if gastrointestinal pathology (eg, peptic

ulcer, large hiatus hernia, etc) is suspected based on

clinical assessment.

Conclusion

This position statement is not intended to provide

inflexible rules or requirements of practice, nor

to establish a local standard of care. Clinical

practitioners must use their own judgement in

selecting the best evidence-based treatment for

patients with informed consent. Physicians should

follow a reasonable course of action based on current

knowledge, available resources, and the needs of

the patient to deliver effective and safe medical

care. The sole purpose of this position statement is

to assist practitioners in achieving this objective.

This position statement was developed under the

auspices of HKSMBS position statement committee

and approved by the members of executive council.

These recommendations were considered valid at

the time of production based on the data available.

New developments in medical research and practice

will be reviewed, and the position statement will be

periodically updated.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: SKH Wong.

Analysis or interpretation of data: SYW Liu, SKH Wong.

Drafting of the manuscript: SYW Liu, CMS Lai, SKH Wong.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual

content: SYW Liu, CMS Lai, SKH Wong.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Declaration

This position statement has been endorsed by the Hong Kong

Association for the Study of Obesity. An abridged version of

the position statement has been published on the website of

the Hong Kong Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery

(

http://www.hksmbs.org/).

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight

and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of

Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on

Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation

2014;129 (25 Suppl 2):S102-38.

Crossref2. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight.

Available from:

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight . Accessed 14 May 2024.

3. Ko GT, Tang J, Chan JC, et al. Lower BMI cut-off value to

define obesity in Hong Kong Chinese: an analysis based on

body fat assessment by bioelectrical impedance. Br J Nutr

2001;85:239-42.

Crossref4. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index

for Asian populations and its implications for policy and

intervention strategies. Lancet 2004;363:157-63.

Crossref5. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic.

Report of a WHO consultation [editorial]. World Health

Organ Tech Rep Ser 2000;894:i-xii, 1-253.

6. Non-Communicable Disease Branch, Centre for Health

Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Report of Population Health Survey 2020-22

(Part II). 2023. Available from:

https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/dh_phs_2020-22_part_2_report_eng.pdf. Accessed 14 May 2024.

7. Buchwald H. The evolution of metabolic/bariatric surgery.

Obes Surg 2014;24:1126-35.

Crossref8. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity: National

Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference

Statement [editorial]. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;55(2

Suppl):615S-619S.

Crossref9. Consensus Development Conference Panel, NIH Conference. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe

obesity. Consensus Development Conference Panel

[editorial]. Ann Intern Med 1991;115:956-61.

Crossref10. Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric

surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA

2004;292:1724-37.

Crossref11. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al. Bariatric surgery

versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year

outcomes. N Engl J Med 2017;376:641-51.

Crossref12. Arterburn DE, Telem DA, Kushner RF, Courcoulas AP.

Benefits and risks of bariatric surgery in adults: a review.

JAMA 2020;324:879-87.

Crossref13. Chang SH, Stoll CR, Song J, Varela JE, Eagon CJ, Colditz GA.

The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery: an updated

systematic review and meta-analysis, 2003-2012. JAMA

Surg 2014;149:275-87.

Crossref14. Liu SY, Wong SK, Lam CC, Yung MY, Kong AP, Ng EK.

Long-term results on weight loss and diabetes remission

after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for a morbidly obese

Chinese population. Obes Surg 2015;25:1901-8.

Crossref15. Lee Y, Doumouras AG, Yu J, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve

gastrectomy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric

bypass: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight

loss, comorbidities, and biochemical outcomes from

randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg 2021;273:66-74.

Crossref16. Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, et al. Weight and type

2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and

meta-analysis. Am J Med 2009;122:248-56.e5.

Crossref17. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery

in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by International Diabetes Organizations.

Diabetes Care 2016;39:861-77.

Crossref18. Sullivan S, Edmundowicz SA, Thompson CC. Endoscopic

bariatric and metabolic therapies: new and emerging

technologies. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1791-801.

Crossref19. Winder JS, Rodriguez JH. Emerging endoscopic

interventions in bariatric surgery. Surg Clin North Am

2021;101:373-9.

Crossref20. Mui WL, So WY, Yau PY, et al. Intragastric balloon in ethnic

obese Chinese: initial experience. Obes Surg 2006;16:308-13.

Crossref21. Chan DL, Cruz JR, Mui WL, Wong SK, Ng EK. Outcomes

with intra-gastric balloon therapy in BMI <35 non-morbid

obesity: 10-year follow-up study of an RCT. Obes Surg

2021;31:781-6.

Crossref22. Wong SK, So WY, Yau PY, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable

gastric banding for the treatment of morbidly obese

patients: early outcome in a Chinese cohort. Hong Kong

Med J 2005;11:20-9.

23. Wu T, Wong SK, Law BT, et al. Bariatric surgery is expensive

but improves co-morbidity: 5-year assessment of patients

with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Br J Surg 2021;108:554-65.

Crossref24. Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, Sugerman HJ, et al. American

Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity

Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric

Surgery medical guidelines for clinical practice for the

perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical

support of the bariatric surgery patient. Obesity (Silver

Spring) 2009;17 Suppl 1:S1-70, v.

Crossref25. Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, et al. Clinical practice

guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and

nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient—2013

update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical

Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American

Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Obesity (Silver

Spring) 2013;21 Suppl 1(01):S1-27.

Crossref26. Mechanick JI, Apovian C, Brethauer S, et al. Clinical

practice guidelines for the perioperative nutrition,

metabolic, and nonsurgical support of patients undergoing

bariatric procedures—2019 update: cosponsored by

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, The Obesity Society,

American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery,

Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of

Anesthesiologists. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:O1-58.

Crossref27. Di Lorenzo N, Antoniou SA, Batterham RL, et al. Clinical

practice guidelines of the European Association for

Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) on bariatric surgery: update

2020 endorsed by IFSO-EC, EASO and ESPCOP. Surg

Endosc 2020;34:2332-58.

Crossref28. ASGE/ASMBS Task Force on Endoscopic Bariatric

Therapy. A pathway to endoscopic bariatric therapies. Surg

Obes Relat Dis 2011;7:672-82.

Crossref29. Eisenberg D, Shikora SA, Aarts E, et al. 2022 American

Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and

International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and

Metabolic Disorders (IFSO): indications for metabolic and

bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2022;18:1345-56.

Crossref30. Kasama K, Mui W, Lee WJ, et al. IFSO-APC consensus

statements 2011. Obes Surg 2012;22:677-84.

Crossref31. Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome—a

new world-wide definition. A consensus statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med

2006;23:469-80.

Crossref32. NICE guideline [NG28]. Type 2 diabetes in adults:

management. London: National Institute for Health and

Care Excellence (NICE); 2022.

33. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Kansagara D, et al. Hemoglobin A1c

targets for glycemic control with pharmacologic therapy

for nonpregnant adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a

guidance statement update from the American College of

Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2018;168:569-76.

Crossref34. Gómez V, Woodman G, Abu Dayyeh BK. Delayed gastric

emptying as a proposed mechanism of action during

intragastric balloon therapy: results of a prospective study.

Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016;24:1849-53.

Crossref35. Ali MR, Moustarah F, Kim JJ; American Society

for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Clinical Issues

Committee. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric

Surgery position statement on intragastric balloon therapy

endorsed by the Society of American Gastrointestinal and

Endoscopic Surgeons. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2016;12:462-7.

Crossref