Hong Kong Med J 2024 Jun;30(3):209–17 | Epub 21 May 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Healthy Eating Report Card for Pre-school Children in Hong Kong

Alison WL Wan, MSc; Kevin KH Chung, PhD; JB Li, MEd, PhD; Derwin KC Chan, MSc, PhD

Department of Early Childhood Education, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Derwin KC Chan (derwin@eduhk.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to develop the

Healthy Eating Report Card for Pre-school Children

in Hong Kong for evaluating the prevalence of healthy

eating behaviours and favourable family home food

environments (FHFEs) among pre-school children

in Hong Kong.

Methods: In this cross-sectional study, 538 parent-child

dyads from eight kindergartens in Hong Kong

were recruited. Parents or guardians completed a

questionnaire comprising Report Card items. The

Report Card included two indicators of Children’s

Eating Behaviours (ie, Children’s Dietary Patterns

and Children’s Mealtime Behaviours) and three

indicators of FHFEs (ie, Parental Food Choices and

Preparation, Avoidance of Unhealthy Foods, and

Family Mealtime Environments). Each indicator

and its specific items were assigned a letter grade

representing the percentage of participants

achieving the predefined benchmarks. The grades

were defined as A (≥80%, Excellent); B (60%-79%,

Good); C (40%-59%, Fair); D (20%-39%, Poor); and F

(<20%, Very poor). Plus (+) and minus (-) signs were

used to indicate the upper or lower 5% of each grade.

Results: Overall, Children’s Eating Behaviours were classified as Fair (average grade of ‘C’), whereas

FHFEs were classified as Good (average grade

of ‘B’). The sub-grades ranged from ‘C’ to ‘A-’, as

follows: Children’s Dietary Patterns, ‘C+’; Children’s

Mealtime Behaviours, ‘C’; Parental Food Choices and

Preparation, ‘C+’; Avoidance of Unhealthy Foods, ‘B’;

and Family Mealtime Environments, ‘A-’.

Conclusion: The findings highlight areas for

improvement in healthy eating among children.

The Healthy Eating Report Card could offer novel

insights into intervention tools that promote healthy

eating.

New knowledge added by this study

- Eating behaviours among pre-school children in Hong Kong were classified as Fair (average grade of ‘C’).

- Among those children, family home food environments (FHFEs) were classified as Good (average grade of ‘B’).

- There is considerable potential for improvement in children’s dietary patterns, children’s mealtime behaviours, and parental food choices and preparation.

- The Healthy Eating Report Card for Pre-school Children can be considered a useful tool for evaluating the prevalence of healthy eating behaviours and favourable FHFEs among pre-school children.

- The grades provided by the Report Card offer valuable guidance concerning how healthy eating behaviours and favourable FHFEs among pre-school children could be promoted at the family, school, and community levels.

Introduction

Unhealthy dietary patterns, generally characterised

by low dietary diversity, skipping breakfast, low

consumption of fruits and vegetables, and frequent

consumption of energy-dense/nutrient-poor foods

and sugar-sweetened beverages, are common

among children worldwide.1 2 It is particularly

important for young children to adopt healthy

dietary patterns because eating habits and food

preferences in childhood can influence dietary

patterns in adulthood.3 Similar to children in other regions, Hong Kong children have a high prevalence

of unhealthy dietary patterns.4 A cross-sectional

survey evaluating infant and young child feeding

practices in Hong Kong identified numerous dietary

problems, including dietary imbalance (eg, high

protein but low fibre intake), overdependence on the

use of formula milk, inadequate intake of vegetables

and fruits, and unhealthy snacking and sugary

beverage habits.5 A previous study revealed a need for dietary improvement among Hong Kong pre-school

children.6 Key recommendations included a balanced diet, better nutritional adequacy, and

greater independence during mealtimes (ie, self-feeding).6 Indeed, inappropriate behaviours during

mealtimes, such as lack of self-feeding, food refusal,

picky eating, and prolonged meals, are common

in young children.7 8 Children with inappropriate

mealtime behaviours may be susceptible to

insufficient nutrient and/or energy intake.9 However,

there is limited information available regarding the

mealtime behaviours of typically developing pre-school

children in Hong Kong.

Family home food environments (FHFEs), ie,

parental food choices and preparation, avoidance of

unhealthy foods, and family mealtime environments,

have strong associations with children’s dietary habits

and body weight.10 11 12 Parental use of nutrition labels

to make healthier food choices has been linked to a

lower probability of overweight or obesity in their

children.13 Similarly, children with limited access

to unhealthy foods are reportedly more likely to

maintain a normal body weight.14 A review focusing

on the effects of family and social environment on

children’s dietary patterns found that a structured

mealtime environment—namely, regular meals with

family members and screen-free mealtimes—was

associated with healthy food consumption patterns

in children.15 In summary, children’s mealtime

behaviours and FHFEs are important for healthy

eating among young children. Thus far, no studies

have provided an overview of eating behaviours and FHFEs among pre-school children in Hong Kong.

The use of a report card at the country-/region-level can provide a valuable overview of

the prevalence of health behaviours through a

conventional letter grading system (ranging from

A+ to F).16 This framework has been used to evaluate

various health-related behaviours (eg, physical

activity,17 18 19 sedentary behaviour,17 18 19 smoking

behaviour,20 and dietary patterns20 21 22) in children and

youth. The findings of such report cards offer insights

concerning the extent to which health behaviours

are adopted in specific communities and provide

targeted recommendations for health behaviours

at the individual or public level.16 23 Moreover, the

publication of these report cards can facilitate health

promotion awareness and catalyse policy changes

that motivate individuals to commit to health

behaviours.16 19 24 Thus far, only one published report

card (the Healthy Active Kids South Africa [HAKSA]

Report Card) has revealed dietary patterns among

children and youth.21 However, the HAKSA Report

Card only covered the intake of fruits, vegetables, and

unhealthy snacks; other essential aspects of healthy

eating (eg, daily breakfast consumption, dietary

variety, mealtime behaviours, and FHFEs) were

not considered. Additionally, because the evidence

underlying the grading criteria for various aspects of

healthy eating was not explicitly stated, the findings

of the HAKSA Report Card might not provide useful

benchmarks concerning how well individuals adhere

to healthy eating standards or recommendations

adopted by health authorities. Therefore, we aimed

to address the aforementioned research gaps

through a cross-sectional study that developed the

Healthy Eating Report Card for Pre-school Children

in Hong Kong, using a grading scale and evidence-based

benchmarks to assess the current prevalence

of healthy eating behaviours and favourable FHFEs

among pre-school children in Hong Kong.

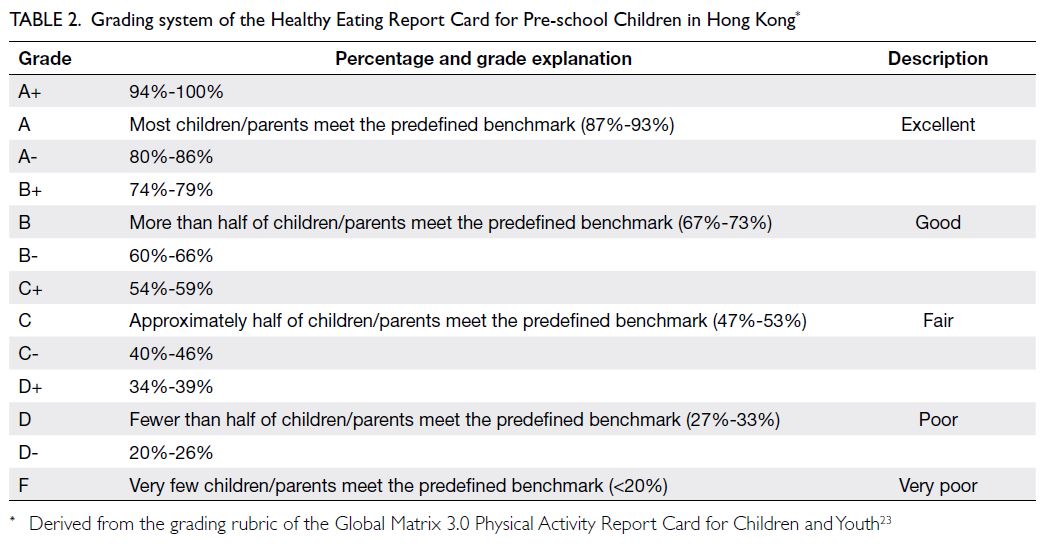

Our Report Card assesses various indicators of

Children’s Eating Behaviours (ie, Children’s Dietary

Patterns and Children’s Mealtime Behaviours) and

FHFEs (ie, Parental Food Choices and Preparation,

Avoidance of Unhealthy Foods, and Family Mealtime

Environments). Each indicator and its specific items

are assigned letter grades based on predefined

benchmarks, revealing how well pre-school children

in Hong Kong meet the recommendations and

standards established by the government and

published literature concerning pre-school children’s

healthy eating behaviours and FHFEs (Tables 125 26 27 28 29 30 31

and 223). The findings may enhance the understanding

of eating behaviours and FHFEs among pre-school

children in Hong Kong. Additionally, the Healthy

Eating Report Card established in our study will

be useful for future studies examining healthy

eating among young children in other countries or

regions.

Methods

Participants

We recruited 538 Hong Kong parent-child dyads

from eight local kindergartens in three main regions

of Hong Kong (29.55% of children from the New

Territories, 62.64% of children from Kowloon, and

7.81% of children from Hong Kong Island). The

children were aged between 2 and 6 years with a

mean age of 4.10 years (standard deviation=0.92);

49.63% of the children were boys. Of the children,

33.77%, 29.46%, and 36.77% were in grades K1, K2,

and K3, respectively. Respondents were mainly

mothers (85.63%), followed by fathers (13.25%) and

other legal guardians (1.12%). The mean respondent

age was 36.62 years (standard deviation=5.84).

Procedures

This cross-sectional study examined the prevalence

of healthy eating behaviours and favourable FHFEs

among Hong Kong pre-school children in October

2021. We sent invitation letters to 89 randomly

selected local kindergartens across 18 districts

in Hong Kong (excluding international schools

and special needs schools). Eight kindergartens

agreed to participate in this study and distribute

our questionnaire to eligible parents. The inclusion

criteria required participants to: (1) be Chinese parents or guardians; (2) have at least one child in

grades K1 to K3; and (3) have sufficient Chinese

reading ability to complete the questionnaire. Schools

and parents were both asked to provide written

informed consent. Parents completed a parent-reported

questionnaire (comprising the Healthy

Eating Report Card items) about their children’s

eating behaviours and FHFEs, which typically

required 15 minutes to complete. Respondents

received a HK$50 supermarket voucher as a token of

appreciation for their participation.

Report Card questionnaire

The design of our Healthy Eating Report Card was

based on the conceptual framework established by

the Report Card on Physical Activity for Children

and Youth, which offers a comprehensive grading

framework and benchmarks to evaluate health

behaviours.16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 The Global Matrix 3.0 Physical

Activity Report Card for Children and Youth has

been used in 49 countries to evaluate the prevalence

of physical activity behaviours among children and

youth.23 Using a similar assessment framework, our

Healthy Eating Report Card evaluated the prevalence

of healthy eating behaviours and favourable FHFEs

among Hong Kong pre-school children. The Healthy

Eating Report Card Questionnaire consisted of

21 items which were developed based on the healthy eating guidelines and recommendations

of the Department of Health of Hong Kong.25 26

The items were aligned with the five indicators of

our Report Card, including two Children’s Eating

Behaviours indicators (ie, Children’s Dietary

Patterns and Children’s Mealtime Behaviours) and

three FHFEs indicators (ie, Parental Food Choices

and Preparation, Avoidance of Unhealthy Foods,

and Family Mealtime Environments), to determine

whether the children adhered to healthy eating

behaviours and were involved in healthy FHFEs.

Participants responded to questionnaire items

using a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from ‘always’

to ‘never’), yes/no questions, open-ended questions,

and multiple-choice questions. The questionnaire is

provided in online supplementary Appendix 1.

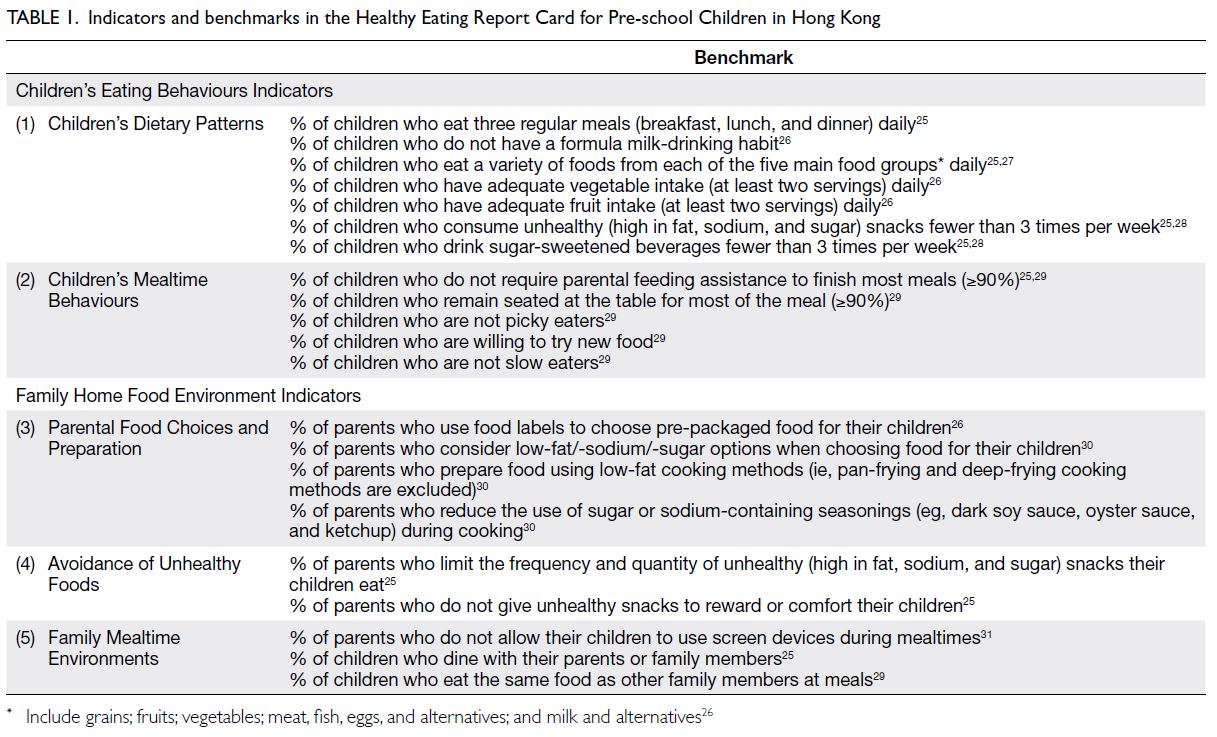

Data analysis

Benchmarks for each indicator were established

in accordance with recommendations and

guidelines for healthy eating behaviours and

FHFEs from the Hong Kong SAR Government and

published literature.25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Based on the results of the

questionnaire, we used a benchmark framework

to determine the letter grade for each indicator

that reflected the percentage of participants who

met the predetermined benchmarks. A sub-grade

was also determined for each indicator item. The

questionnaire items and criteria of questionnaire

answers related to the benchmarks are displayed

in online supplementary Appendix 2.25 26 28 29 30 31 The

grading system for the Healthy Eating Report

Card was derived from the grading rubric of the

Global Matrix 3.0 Physical Activity Report Card

for Children and Youth, ie, A (≥80%, Excellent); B (60%-79%, Good); C (40%-59%, Fair); D (20%-39%,

Poor); and F (<20%, Very poor).23 Plus (+) and minus

(-) signs were used to show the upper or lower 5%

of each grade.23 The proposed benchmarks and the

grading scheme are shown in Tables 125 26 27 28 29 30 31 and 2,23

respectively.

Table 1. Indicators and benchmarks in the Healthy Eating Report Card for Pre-school Children in Hong Kong

Due to the percentage calculation, responses

to 5-point Likert scale questions in the questionnaire

were converted to binary variables; responses of

‘sometimes’, ‘often’ and ‘always’ were categorised as

‘yes’, whereas responses of ‘never’ and ‘rarely’ were

categorised as ‘no’.32 All statistical analyses were

performed using SPSS software (Windows version

26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

Missing values ranged from 0.19% to 2.79% for

questionnaire items because of nonresponses to

some items. The descriptive statistics revealed valid

percentages for each indicator item, along with 95%

confidence intervals (CIs). The arithmetic mean

for each indicator was calculated by summing the

valid percentage for each item of the indicator, then

dividing that value by the number of corresponding

items. This arithmetic mean represents the average

percentage of participants who met predefined

benchmarks for that indicator.

Results

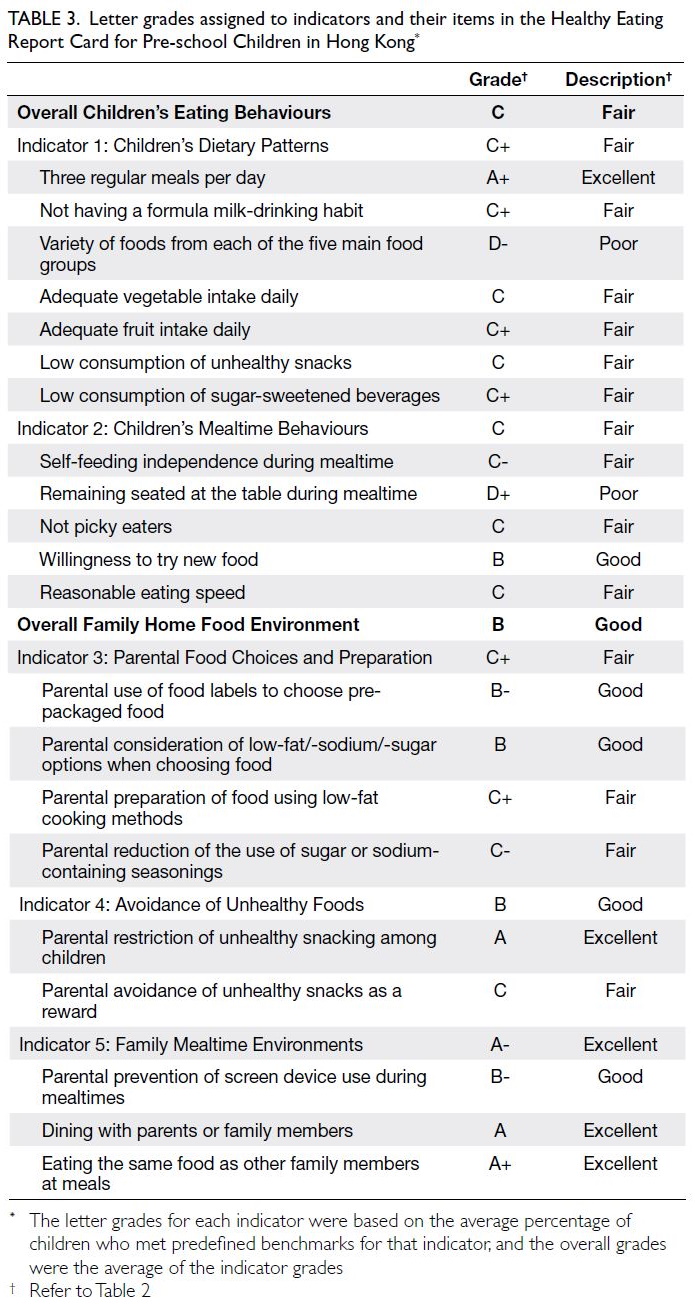

The letter grades of our Healthy Eating Report

Card are summarised in Table 3. The descriptive

statistics of the Report Card are displayed in online supplementary Appendix 3. The average grades of Children’s Eating Behaviours indicators and FHFEs

indicators were ‘C’ and ‘B’, respectively, showing

that the eating behaviours of Hong Kong pre-school

children were classified as Fair, whereas FHFEs were classified as Good (Table 3). On average, nearly half

of the pre-school children (52.88%; 95% CI=51.26%-54.50%) adhered to healthy eating behaviours,

whereas more than half of the parents (70.87%; 95%

CI=69.34%-72.40%) provided their children with

favourable FHFEs.

Table 3. Letter grades assigned to indicators and their items in the Healthy Eating Report Card for Pre-school Children in Hong Kong

Children’s Dietary Patterns

Nearly all children (97.58%) had three regular meals

daily. However, only 24.34% of the children ate a

variety of foods. Approximately half of the children

had adequate vegetable and fruit intakes (50.84%

and 58.40%, respectively). Moreover, 55.76% did not

have a formula milk-drinking habit. Additionally,

around half of the children had low consumption

of unhealthy snacks and sugary beverages (52.25%

and 58.87%, respectively) [online supplementary Appendix 3]. Overall, Children’s Dietary Patterns

was graded ‘C+’ (Fair), signifying that approximately

half of the children (55.37%; 95% CI=53.98%-56.75%)

adhered to healthy dietary patterns.

Children’s Mealtime Behaviours

Fewer than half of the children (43.02%) did not

require parental assistance to finish a meal. Only

38.32% of the children could remain seated during

mealtimes. Of the children, 49.15% and 67.98%

did not exhibit picky eating behaviours and were

willing to try new foods, respectively. Nearly half

of the children (49.35%) did not exhibit slow-eating

behaviours (online supplementary Appendix 3). Children’s Mealtime Behaviours was graded

‘C’ (Fair), showing that approximately half of the

children (49.92%; 95% CI=46.28%-55.07%) exhibited

desirable mealtime behaviours.

Parental Food Choices and Preparation

More than half of the parents (63.69%) used nutrition

labels. Similarly, more than half of the parents

(70.26%) considered low oil/salt/sugar food options

for their children. Approximately half of the parents

used low-fat cooking methods and reduced the use

of sugar- or salt-containing condiments (53.53%

and 43.58%, respectively) [online supplementary Appendix 3]. Parental Food Choices and Preparation

was graded ‘C+’ (Fair), revealing that approximately

half of the parents (57.88%; 95% CI=55.49%-60.28%)

made healthy food choices and prepared healthy

meals for their children.

Avoidance of Unhealthy Foods

Half of the parents (52.04%) did not reward their

children with unhealthy snacks or drinks. A

large majority of the parents (90.15%) limited the

frequency and quantity of unhealthy foods (online supplementary Appendix 3). Therefore, Avoidance

of Unhealthy Foods was graded ‘B’ (Good), signifying that more than half of the parents (71.10%; 95%

CI=68.66%-73.53%) controlled their children’s access

to unhealthy foods.

Family Mealtime Environments

A large majority of the children dined with their

parents or family members and ate the same food

as other family members (93.47% and 95.50%, respectively). More than half of the parents (61.08%)

did not allow their children to use screen devices

during mealtimes (online supplementary Appendix 3). Family Mealtime Environments was graded ‘A-’

(Excellent), showing that most children (83.46%;

95% CI=81.63%-85.29%) were involved in structured

family mealtime environments.

Discussion

This study aimed to develop the Healthy Eating

Report Card for Pre-school Children in Hong Kong,

which assessed the prevalence of healthy eating

behaviours and favourable FHFEs among pre-school

children in Hong Kong. We established evidence-based

benchmarks to guide the process of grading

Children’s Eating Behaviours indicators and FHFEs

indicators, then utilised letter grades to illustrate how

well children adhered to healthy eating behaviours.

Children’s Dietary Patterns and Children’s Mealtime

Behaviours were graded ‘C+’ and ‘C’, respectively,

signifying that eating behaviours in Hong Kong pre-school

children were Fair; the average overall grade

was ‘C’. Our findings indicate that approximately half

of the pre-school children in Hong Kong adhered to

healthy eating behaviours. Parental Food Choices

and Preparation, Avoidance of Unhealthy Foods,

and Family Mealtime Environments were graded

‘C+’, ‘B’, and ‘A-’, respectively, showing that FHFEs

were Good; the average overall grade was ‘B’. Our

results revealed that more than half of the pre-school

children in Hong Kong were involved in a

healthy home eating environment. Taken together,

these findings enhance the understanding of pre-school

children’s eating behaviours and FHFEs in

Hong Kong.

Comparison of Report Card findings with Hong Kong’s previous data

Our Report Card showed that the eating behaviours

of Hong Kong pre-school children were classified as

Fair; some unhealthy dietary patterns and undesirable

mealtime behaviours were prevalent because

nearly half of the children did not meet predefined

benchmarks for Children’s Eating Behaviours

indicators. Previous research33 concerning the

eating habits of Hong Kong pre-school children

showed that more than half of the surveyed children

(78.8%) had a habit of eating breakfast. Nevertheless,

fewer than half of the children achieved the

recommended daily intakes of vegetables (19.6%)

and fruits (47.3%), respectively.33 Some studies

identified a high prevalence of formula milk drinking

among Hong Kong pre-school–aged children, such

that 77% of 4-year-old children continue to drink

formula milk.5 34 Overdependence on formula milk

may reduce appetite in children and impede their

development of healthy eating habits.35 Lo et al33 found that, on average, children consumed high

energy-dense foods (eg, candy/chocolate, sweet

crackers, and sugary beverages) more than twice per

week; accordingly they suggested that such children

should minimise their consumption of these foods.

Additionally, an investigation regarding undesirable

mealtime behaviours among Hong Kong pre-school

children revealed that approximately 70% of the

children required >30 minutes to finish a meal;

these children often were unwilling to self-feed or

finish their meals.6 The present study are consistent

with previous research, indicating that there is

considerable potential for improvement in eating

behaviours among Hong Kong children.

Comparison of Report Card findings with

international data

As mentioned above, the HAKSA Report Card

assessed a few aspects of the dietary patterns of

South African children and youth aged 3 to 8 years

in 2018. Although using a grading rubric similar

to our Report Card, the HAKSA Report Card only

involved two indicators, namely Fruit and Vegetable

Intake (graded ‘D’) and Snacking, Sugar-Sweetened

Beverages, Dietary Sodium, and Fast Food Intake

(graded ‘F’).21 Our Report Card may provide better

coverage of healthy dietary patterns because it

included assessments of regular daily meals, food

variety, and formula milk-drinking habits, with a

particular focus on pre-school children aged 2 to 6

years. Despite the discrepancies between studies,

the healthy dietary patterns observed in our Report

Card were more favourable than patterns observed

in the HAKSA Report Card.21 This difference also

implies that standards for healthy eating behaviours

among children differ between South Africa and

Hong Kong. Future studies should develop a cross-ountry/region–level Report Card and establish

a global benchmark to comprehensively analyse

global variations in healthy eating, thereby raising

global awareness and stimulating global discussion

regarding the promotion of healthy eating.

Novel findings on family home food environments

Very little is known about FHFEs of children in

Hong Kong; therefore, the present study provides

initial information concerning parental food choices

and preparation, avoidance of unhealthy foods, and

family mealtime environments among Hong Kong

pre-school children. Based on our findings, the

FHFEs of the pre-school children in Hong Kong were

classified as Good. This result suggests that parents

in Hong Kong attempt to promote healthy diets by

limiting their children’s consumption of unhealthy

foods. A previous study revealed that Hong Kong

parents tended to adopt the ‘control over eating’ approach to feed their children, whereby parents

primarily determine the amounts of food that

children should eat, including unhealthy snacks.33

Moreover, parents often used food to reward or

comfort children.36 The indicator of Family Mealtime

Environments in our Report Card showed that most

pre-school children had a structured family mealtime

environment where they dined with their family and

shared the same food with their family members. This

finding may be attributed to the Chinese cultural

emphasis on shared meals with family members.37

Thus, the results of the present study are consistent

with previous research findings.

However, this high grade for Family Mealtime

Environments may have increased the average grade

for FHFEs indicators. Indeed, parents’ food choices,

purchases, and preparation directly influence

children’s home food environment and food

consumption.38 When we specifically focused on the

Parental Food Choices and Preparation indicator,

the grade decreased to Fair (letter grade of ‘C+’),

signifying that only half of the parents complied

with healthy eating practices for their children,

such as the use of nutrition labels and adoption of

healthy cooking methods. Thus, it is important to

promote healthy eating at home, which will facilitate

healthy eating behaviours among children. A pilot

FHFE intervention of the Healthy Home Offerings

via the Mealtime Environment Plus programme,

which provided parents and children with nutrition

education and meal preparation training and

activities, successfully promoted a structured

mealtime environment at home and helped to

improve dietary intake patterns.39 40 Accordingly,

future studies might utilise nutrition education

interventions to improve the FHFEs of pre-school

children in Hong Kong.

Strengths and limitations

This study had some strengths. In particular, we

collected primary data to enhance the understanding

of eating behaviours and FHFEs among pre-school

children in Hong Kong. Moreover, to our knowledge,

this is the first use of a report card framework to

comprehensively evaluate the prevalence of healthy

eating behaviours among pre-school children.41 The

Report Card can serve as an effective awareness-raising

tool that provides novel insights concerning

the promotion of healthy eating behaviours, as well

as recommendations for healthy eating policies and

healthy food environments.23

However, this study also had several limitations.

First, its cross-sectional design precluded the

identification of changes in children’s eating

behaviours and FHFEs over time. Future studies could

perform longitudinal measurements of variables

in the Report Card to reveal changes or stability in

healthy eating behaviours among young children; such measurements could also determine whether

Report Card scores are predictive of health outcomes

in children. An individual-level Healthy Eating

Report Card should be developed in future studies

to examine the effectiveness of the Report Card on

parental intentions towards healthy eating, as well as

children’s healthy eating behaviours and favourable

FHFEs. Second, although the items of the Healthy

Eating Report Card Questionnaire were developed

based on the guidelines and recommendations of the

Hong Kong SAR Government,25 26 the development

of the questionnaire did not include evaluations of

its content validity and psychometric properties.

Future studies should examine the psychometric

properties and other validity aspects of the Report

Card questionnaire (eg, factorial validity, convergent

validity, and discriminant validity).42 Third, the

study relied on parent-reported questionnaires of

children’s eating behaviours and FHFEs, which may

be susceptible to response biases, social desirability

bias, and general response tendencies.43 44 Validation

studies comparing parent-reported questionnaires

with more objective measures of children’s food

intake and observational assessments of mealtime

behaviours could be conducted in the future. Finally,

the current Report Card does not reflect several

components of children’s eating behaviours (eg, the

frequency of dining out and the variety of vegetable

and fruit consumption) and FHFEs (eg, parental

feeding practices and accessibility of healthy food

at home). Future studies should investigate whether

these components could be included within the

Healthy Eating Report Card to provide a more

holistic assessment of healthy eating among children.

Conclusion

This study developed the Healthy Eating Report

Card for Pre-school Children in Hong Kong to

reflect the prevalence of healthy eating behaviours

and favourable FHFEs among pre-school children in

Hong Kong. The Report Card revealed that Children’s

Eating Behaviours were classified as Fair (average

grade of ‘C’), whereas FHFEs were classified as Good

(average grade of ‘B’). There is considerable potential

for improvement in children’s eating behaviours (ie,

healthy dietary patterns and appropriate mealtime

behaviours) and FHFEs (particularly concerning

parental healthy food choices and preparation). We

believe that the Report Card can serve as a useful

tool for evaluating the prevalence of healthy eating

behaviours and favourable FHFEs in young children;

it could offer novel insights into strategies for

promotion of healthy eating in pre-school setting.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: AWL Wan, DKC Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: AWL Wan, DKC Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: AWL Wan, DKC Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: AWL Wan, DKC Chan.

Analysis or interpretation of data: AWL Wan, DKC Chan.

Drafting of the manuscript: AWL Wan, DKC Chan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Ms Kiko KH Leung, Ms Roni MY Chiu, and

Ms Tracy CW Tang from the Department of Early Childhood

Education of The Education University of Hong Kong for their

assistance in preparing study materials and collecting data.

The authors also thank the eight participating kindergartens

for aiding in the distribution and collection of questionnaires

from parents.

Funding/support

This research was funded by the Research Impact Cluster

Fund of the Department of Early Childhood Education,

Faculty of Education and Human Development, The

Education University of Hong Kong, through an award to

the corresponding author. The funder had no role in study

design, data collection/analysis/interpretation or manuscript

preparation.

Ethics approval

The study protocol of this research was approved by the

Human Research Ethics Committee of The Education

University of Hong Kong (Ref No.: 2020-2021-0420). All

schools and parents provided written informed consent for

participation in this research and have also consented to the

publication of its findings.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and

may include some information that was not peer reviewed.

Accepted supplementary material will be published as

submitted by the authors, without any editing or formatting.

Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely

those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong

Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical

Association. The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the

Hong Kong Medical Association disclaim all liability and

responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. World Health Organization. Healthy diet. 2020. Available

from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet. Accessed 9 Jul 2022.

2. Kupka R, Siekmans K, Beal T. The diets of children:

overview of available data for children and adolescents.

Glob Food Sec 2020;27:100442. Crossref

3. Movassagh EZ, Baxter-Jones AD, Kontulainen S, Whiting SJ,

Vatanparast H. Tracking dietary patterns over 20 years

from childhood through adolescence into young adulthood: the Saskatchewan Pediatric Bone Mineral Accrual Study. Nutrients 2017;9:990.Crossref

4. Department of Health. Hong Kong SAR Government.

Diet, physical activity and health: Hong Kong situation.

2010. Available from: https://www.change4health.gov.hk/filemanager/common/image/strategic_framework/action_plan/action_plan_2_e.pdf . Accessed 5 Jul 2022.

5. Woo J, Chan R, Li L, Luk WY. A survey of infant and young

child feeding in Hong Kong: diet and nutrient intake. 2012.

Available from: https://www.fhs.gov.hk/english/reports/files/Diet_nutrientintake_executive%20summary_2504.pdf . Accessed 5 Jul 2022.

6. Yip PS, Chan VW, Lee QK, Lee HM. Diet quality and eating

behavioural patterns in preschool children in Hong Kong.

Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2017;26:298-307. Crossref

7. Crist W, Napier-Phillips A. Mealtime behaviors of young

children: a comparison of normative and clinical data. J

Dev Behav Pediatr 2001;22:279-86. Crossref

8. Archer LA, Rosenbaum PL, Streiner DL. The children’s

eating behavior inventory: reliability and validity results. J

Pediatr Psychol 1991;16:629-42. Crossref

9. Samuel TM, Musa-Veloso K, Ho M, Venditti C, Shahkhalili-Dulloo Y. A narrative review of childhood picky eating and its relationship to food intakes, nutritional status, and

growth. Nutrients 2018;10:1992. Crossref

10. Boswell N, Byrne R, Davies PS. Family food environment

factors associated with obesity outcomes in early

childhood. BMC Obes 2019;6:17. Crossref

11. Vereecken C, Haerens L, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Maes L. The

relationship between children’s home food environment

and dietary patterns in childhood and adolescence. Public

Health Nutr 2010;13:1729-35. Crossref

12. Rex SM, Kopetsky A, Bodt B, Robson SM. Relationships

among the physical and social home food environments,

dietary intake, and diet quality in mothers and children. J

Acad Nutr Diet 2021;121:2013-20.e1. Crossref

13. Chang HH, Nayga RM Jr. Mother’s nutritional label use

and children’s body weight. Food Policy 2011;36:171-8. Crossref

14. Nepper MJ, Chai W. Associations of the home food

environment with eating behaviors and weight status

among children and adolescents. J Nutr Food Sci

2015(S12):1-5. Crossref

15. Patrick H, Nicklas TA. A review of family and social

determinants of children’s eating patterns and diet quality.

J Am Coll Nutr 2005;24:83-92. Crossref

16. Coppinger T, Milton K, Murtagh E, et al. Global Matrix

3.0 Physical Activity Report Card for Children and Youth: a

comparison across Europe. Public Health 2020;187:150-6. Crossref

17. Huang WY, Wong SH, Sit CH, et al. Results from the Hong

Kong’s 2018 Report Card on physical activity for children

and youth. J Exerc Sci Fit 2019;17:14-9. Crossref

18. Barnes JD, Colley RC, Tremblay MS. Results from the

Active Healthy Kids Canada 2011 Report Card on Physical

Activity for Children and Youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab

2012;37:793-7. Crossref

19. Tremblay MS, Barnes JD, Bonne JC. Impact of the Active

Healthy Kids Canada report card: a 10-year analysis. J Phys

Act Health 2014;11 Suppl 1:S3-20. Crossref

20. De Villiers A, Steyn N, Coopoo Y, et al. Healthy Active

Kids. South Africa Report Card 2010. 2010. Available

from: https://www.activehealthykids.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/south-africa-report-card-long-form-2010.pdf. Accessed 5 Jul 2022.

21. Draper CE, Tomaz SA, Bassett SH, et al. Results from

the Healthy Active Kids South Africa 2018 Report Card.

SAJCH 2019;13:130-6. Crossref

22. Draper C, Basset S, de Villiers A, Lambert EV; HKKSA

Writing Group. Results from South Africa’s 2014 Report

Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. J Phys

Act Health 2014;11 Suppl 1:S98-104. Crossref

23. Aubert S, Barnes JD, Abdeta C, et al. Global Matrix 3.0

Physical Activity Report Card grades for children and

youth: results and analysis from 49 countries. J Phys Act

Health 2018;15:S251-73. Crossref

24. Tremblay MS, Gray CE, Akinroye K, et al. Physical activity

of children: a global matrix of grades comparing 15

countries. J Phys Act Health 2014;11 Suppl 1:S113-25. Crossref

25. Family Health Service, Department of Health, Hong Kong

SAR Government. Healthy eating for preschool children (2

years to 5 years old). 2022. Available from: https://www.fhs.gov.hk/english/health_info/child/12185.html. Accessed 5 Jul 2022.

26. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Nutrition guidelines for children

aged 2 to 6. Revised 2018. Available from: https://www.startsmart.gov.hk/files/pdf/nutritional_guide_en.pdf. Accessed 5 Jul 2022.

27. United Nations World Food Programme. Food

consumption score nutritional quality analysis (FCS-N)

guidelines. 2015. Available from: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000007074/download/. Accessed 5 May 2022.

28. Bui C, Lin LY, Wu CY, Chiu YW, Chiou HY. Association

between emotional eating and frequency of unhealthy food

consumption among Taiwanese adolescents. Nutrients

2021;13:2739. Crossref

29. Family Health Service, Department of Health, Hong Kong

SAR Government. Healthy eating for 6 to 24 month old

children (3) ready to go (12-24 months). 2022. Available

from: https://www.fhs.gov.hk/english/health_info/child/16301.html. Accessed 5 Jul 2022.

30. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Ideas for healthy cooking. 2017.

Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/static/90039.html. Accessed 5 Jul 2022.

31. Family Health Service, Department of Health, Hong Kong

SAR Government. Do your 0-5-years old children need

electronic screen products? 2022. Available from: https://www.fhs.gov.hk/english/health_info/child/30047.html. Accessed 5 Jul 2022.

32. Shim JE, Kim J, Mathai RA; STRONG Kids Research

Team. Associations of infant feeding practices and picky

eating behaviors of preschool children. J Am Diet Assoc 2011;111:1363-8. Crossref

33. Lo K, Cheung C, Lee A, Tam WW, Keung V. Associations

between parental feeding styles and childhood eating

habits: a survey of Hong Kong pre-school children. PLoS

One 2015;10:e0124753. Crossref

34. Yeung S, Chan R, Li L, Leung S, Woo J. Bottle milk feeding

and its association with food group consumption, growth

and socio-demographic characteristics in Chinese young

children. Matern Child Nutr 2017;13:e12341. Crossref

35. Family Health Service, Department of Health, Hong Kong

SAR Government. Healthy eating for infants and young

children—milk feeding. 2022. Available from: https://www.fhs.gov.hk/english/health_info/child/12549.html. Accessed 5 Aug 2022.

36. Wong EM, Sit JW, Tarrant MA, Cheng MM. The

perceptions of obese school children in Hong Kong toward

their weight-loss experience. J Sch Nurs 2012;28:370-8. Crossref

37. Ma G. Food, eating behavior, and culture in Chinese

society. J Ethn Foods 2015;2:195-9. Crossref

38. Nowicka P, Keres J, Ek A, Nordin K, Sandvik P. Changing

the home food environment: parents’ perspectives four

years after starting obesity treatment for their preschool

aged child. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:11293. Crossref

39. Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, et al. The

Healthy Home Offerings via the Mealtime Environment

(HOME) Plus study: design and methods. Contemp Clin

Trials 2014;38:59-68. Crossref

40. Fulkerson JA, Friend S, Horning M, et al. Family home

food environment and nutrition-related parent and child

personal and behavioral outcomes of the Healthy Home

Offerings via the Mealtime Environment (HOME) Plus

program: a randomized controlled trial. J Acad Nutr Diet

2018;118:240-51. Crossref

41. Olstad DL, Raine KD, Nykiforuk CI. Development of a

report card on healthy food environments and nutrition

for children in Canada. Prev Med 2014;69:287-95. Crossref

42. Wan AW, Chung KK, Li JB, Xu SS, Chan DK. An assessment

tool for the international healthy eating report card for

preschool-aged children: a cross-cultural validation across

Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore, and the United States.

Front Nutr 2024;11:1340007. Crossref

43. Chan DK, Ivarsson A, Stenling A, Yang SX, Chatzisarantis NL,

Hagger MS. Response-order effects in survey methods: a

randomized controlled crossover study in the context of

sport injury prevention. J Sport Exerc Psychol 2015;37:666-73. Crossref

44. Chan DK, Stenling A, Yusainy C, et al. Editor’s Choice:

Consistency tendency and the theory of planned behavior:

a randomized controlled crossover trial in a physical

activity context. Psychol Health 2020;35:665-84. Crossref