Hong Kong Med J 2024 Feb;30(1):75–9 | Epub 8 Feb 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Utility and challenges of ultrasound education for medical and allied health students in Asia

Kwok Yin Leung, MD, FRCOG1,2; Kanu Bala, PhD, FRCP3; Jeonh Yeon Cho, MD4; Sudheer Gokhale, MD, FICR5; Akihiko Kikuchi, MD6; Ping Liang, MD,7; Chiou Li Ong, MB, BS, FRCR8; Quan Bao Nguyen-Phuoc, MD, PhD9; Tuangsit Wataganara, MD10; Yung Liang Wan, MD11

1 Gleneagles Hospital Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Bangladesh Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine and Research, University of Science and Technology Chittagong, Dhaka, Bangladesh

4 Department of Radiology, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea

5 Department of Radiology, Sri Aurobindo Institute of Medical Sciences, Sri Aurobindo University, Indore, India

6 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Saitama Medical Center, Saitama Medical University, Moroyama, Japan

7 Department of Ultrasound, Fifth Medical Center of Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital, Beijing, China

8 Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore

9 Department of Medical Imaging, Can Tho University Hospital, Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Can Tho, Vietnam

10 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

11 Department of Medical Imaging and Intervention, Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan

Corresponding author: Prof Yung Liang Wan (ylw0518@cgmh.org.tw)

Introduction

Nearly all medical specialties use ultrasound

for diagnosis and intervention.1 2 Point-of-care

ultrasound (POCUS) enables clinicians to perform

ultrasonographic examinations at the bedside to

assess urgent cases.3 The advantages of ultrasound

examination include portability, lower cost, and the

ability to perform multiplanar and repeated scanning

without ionising radiation. Because ultrasound is the

most operator-dependent imaging modality, formal

education that covers appropriate and optimal use,

specific imaging techniques, and its limitations is

required.4

Ultrasound education is usually targeted

towards postgraduate radiologists, with some

piecemeal training in other specialties. However, the

provision of undergraduate ultrasound education

(UUE) is increasing.1 5 In a recent survey, 72.6% of

medical schools in the United States who responded

reported having an ultrasound curriculum.5 In

another survey, the theoretical background of

ultrasound was taught in 87% of the universities in

Europe who responded, although only a minority

had incorporated ultrasound into the preclinical

curriculum.1 Undergraduate ultrasound education

can enhance understanding of basic medical

sciences, such as anatomy and physiology, provide

a bridge from basic science to clinical science, and

improve the physical examination skills of students.4

However, two reviews of this topic found conflicting

results regarding the value of ultrasound use among

medical students.6 7

Despite being recommended by the World

Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (WFUMB),8 UUE is not popular in Asia according

to our understanding. We recently ran a WFUMB-AFSUMB

(Asian Federation of Societies for

Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology) programme to

provide UUE in Asia. In this commentary, we report

the utility of UUE in Asia and the challenges around

its implementation.

Utility and challenges of undergraduate

ultrasound education in Asia

Between April and June in 2022, a pilot survey

consisting of four open questions about UUE was sent

by the AFSUMB to the presidents or representatives

of 16 affiliated societies.9 The main outcome measure

was the response to the question ‘In addition to

students of medical schools or clinical departments,

is there ultrasound education provided to other

students in medical college?’ Qualitative analysis was

performed on the data collected. Detailed survey

results can be found in the online supplementary Appendix.

Of the 16 AFSUMB-affiliated societies, 10 (62.5%) responded. Training for undergraduates (medical students or allied health professionals) was

provided in three places (30%), namely, mainland

China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Limited ultrasound

education was provided in five places (50%), namely,

Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Thailand, and

Vietnam. The societies in Bangladesh and India

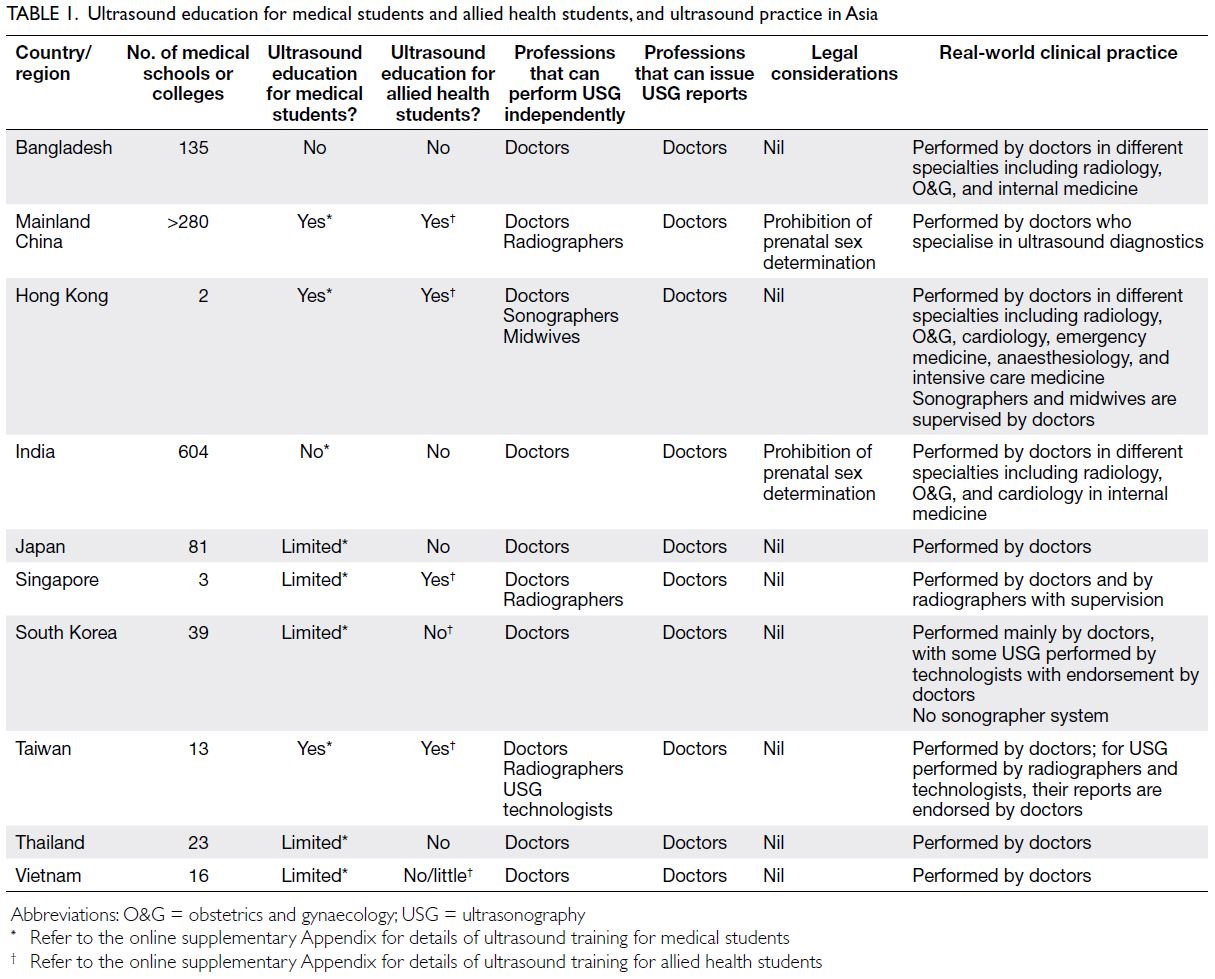

reported that there was no systematic UUE (Table 1).

Table 1. Ultrasound education for medical students and allied health students, and ultrasound practice in Asia

Except India, nine of the ten societies (90%)

reported that the determining factor in deciding

the provision of UUE was whether graduates would be required to perform ultrasound examinations

in hospitals after graduation. The way in which

ultrasound imaging was practised and which

specialities routinely performed it differed between

the societies and geographical locations surveyed

(Table 1). For example, student radiographers in

Taiwan and mainland China received training,

as may be expected, but in Hong Kong, student

midwives also received training and performed

obstetric examinations once qualified. In Taiwan,

qualified radiological technicians performed

ultrasound examinations but their final reports must

be approved by a physician. In Singapore, there was

an initiative whereby medical students were regularly

exposed to radiological practice from the start of their

education in the hope of attracting more residents

to the speciality.10 In Japan, UUE was provided to

medical students who were designated to provide

medical care, which would include ultrasound examinations, in rural areas after their graduation.11

Basic education was provided to student nurses in

mainland China, despite them not being allowed to

perform ultrasound examinations once qualified.

In South Korea, there was no education for allied

health students; however, there was no sonographer

role as medical doctors conducted all ultrasound

examinations. However, if the main aim of UUE

is to improve anatomical knowledge and physical

examination skills, it is questionable whether the

time and money required to implement it would be

justified.6

Unlike the usual issues that hamper the

introduction of UUE, the major issue identified in

India was the Preconception and Prenatal Diagnostics

Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Determination) Act

2003, which bans the use of ultrasound machines by

medical students, technicians, and nurses. Although

similar laws regarding sex selection for non-medical reasons are in place in other Asian countries with

high child sex ratios, to what extent this prohibition

has an effect on UUE in those countries is unknown.12

In Hong Kong, an ultrasound e-learning

module was provided by The University of Hong

Kong and The Chinese University of Hong Kong to

enhance and facilitate students’ learning by making

the material more accessible, relevant, and effective

(online supplementary Appendix).8 13 14 The use of

such an e-learning platform is one of the solutions

to the problems identified around the integration of

ultrasound into medical education, namely, a lack of

trained faculty, requisition of ultrasound machines

for teaching, and limited space in an already full

curriculum.4 13 14 The WFUMB is developing e-learning

that focuses on the development and

distribution of e-learning materials and web-based

simulations to supplement theoretical

knowledge.8 To improve practical skills, the use of

healthy volunteers, mannequins or clinical skills

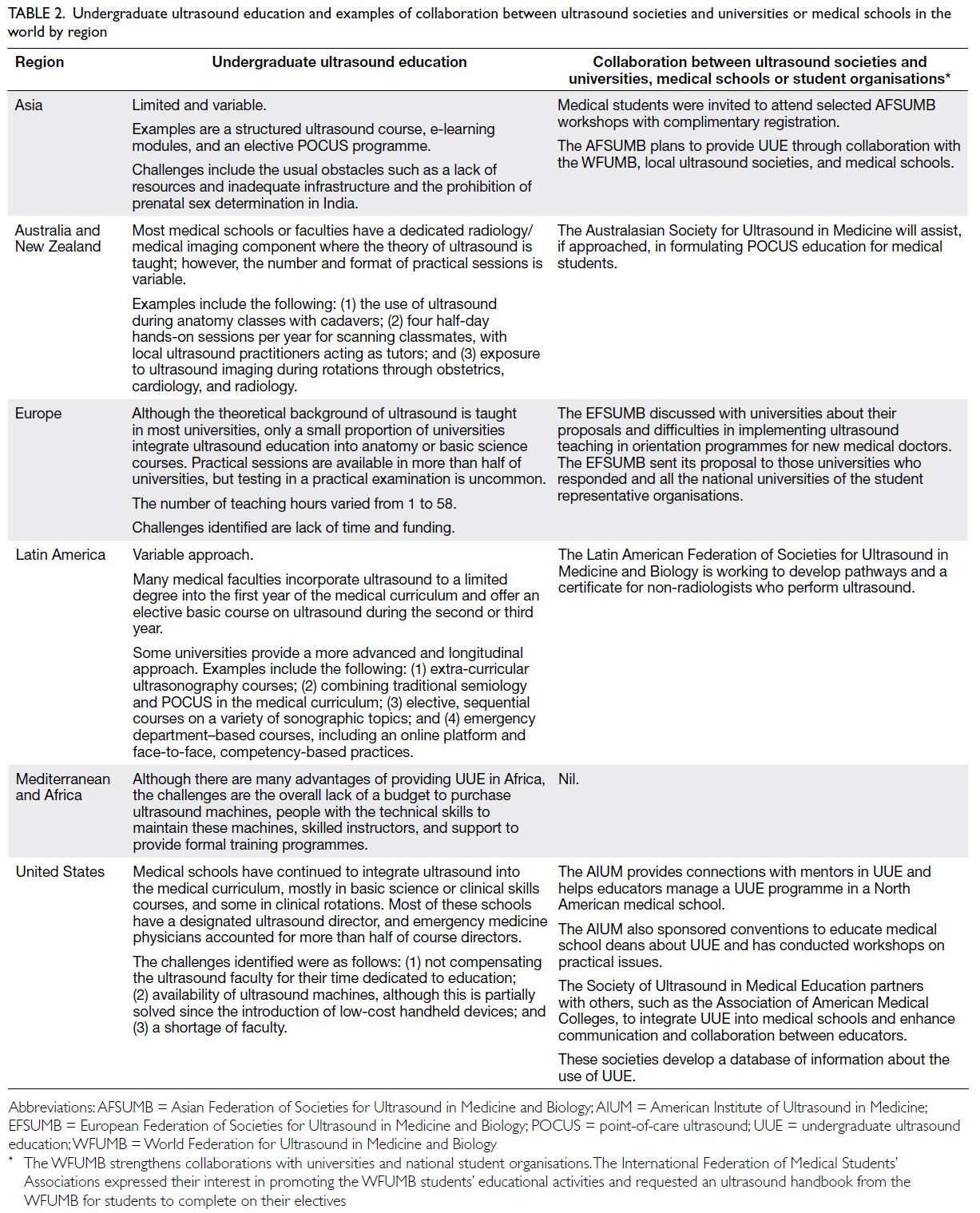

laboratories is required.4 8 11 Finally, collaboration

between ultrasound societies and medical schools is

important for a successful UUE programme (Table 2).8 15

Table 2. Undergraduate ultrasound education and examples of collaboration between ultrasound societies and universities or medical schools in the world by region

Point-of-care ultrasound was introduced in the

two medical schools in Hong Kong and in Taiwan.

After following a transthoracic echo programme

on a 2-week anaesthesia rotation, most students

had learned the basic views and had generally

favourable success rates in identifying obvious

cardiac anomalies, although with some variability.16

These results were consistent with a previous

critical review.6 With the development of portable

or affordable handheld ultrasound devices and the

growing body of evidence supporting its extensive

utility, POCUS has been widely accepted since its

introduction. It is therefore reasonable to suggest

that POCUS training can be incorporated into

undergraduate medical education.2 11

This was the first survey conducted by the

AFSUMB involving the presidents or representatives

from affiliated societies in various places in Asia,

although not all societies responded. Since responses

were not directly collected from medical schools

and/or colleges, it is possible that the information

might not have been up to date. The responses were

descriptive in nature, precluding statistical analysis.

In-depth, repeated surveys of medical schools are

required to gain a better appreciation of the situation

regarding UUE.

As the use of ultrasound and POCUS by various

medical specialties increases and the cost and size

of ultrasound machines decreases, we envisage that

medical students will be increasingly expected to use

ultrasound, or at least understand its use after their

graduation.2 The motivation of students to learn

ultrasound techniques is closely connected to their

future career as doctors17 and their feedback to such education is often positive.16 Medical schools may

adopt different teaching methods due to variations

in teaching methods between different universities

(Table 2).1 5 8 Medical systems also vary significantly

across Asia.8 18 19 20 21 The problems associated with

ultrasound teaching can be partly solved by adding,

for example, an e-learning platform for theoretical

education and training in POCUS as an elective

programme, as discussed above.4 11 13 14 15

Conclusion

The current state of UUE in Asia is in its infancy, as

well as being relatively varied because of the different

educational and medical systems. We believe that

the utility and challenges found in the present survey

will be useful to educators, institutions, and societies

for the development of UUE.

Author contributions

Concept or design: KY Leung, YL Wan.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KY Leung, YL Wan.

Drafting of the manuscript: KY Leung, YL Wan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KY Leung, YL Wan.

Drafting of the manuscript: KY Leung, YL Wan.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This commentary received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the local

institutional review board at Linkou Chang Gung Memorial

Hospital, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan as an

exempt study because it did not involve patients or human

images. All representatives of the responded societies gave

consent for their participation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors

and some information may not have been peer reviewed. Any opinions or

recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s)

and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy of

Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association. The Hong

Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical

Association disclaim all liability and responsibility arising

from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. Prosch H, Radzina M, Dietrich CF, et al. Ultrasound

curricula of student education in Europe: summary of the experience. Ultrasound Int Open 2020;6:E25-33. Crossref

2. Nelson BP, Narula S, Argulian E, Bhagra A, Narula J.

Including insonation in undergraduate medical school

curriculum. Ann Glob Health 2019;85:135. Crossref

3. Moore CL, Copel JA. Point-of-care ultrasonography. N

Engl J Med 2011;364:749-57. Crossref

4. Dietrich CF, Hoffmann B, Abramowicz J, et al. Medical

student ultrasound education: a WFUMB position paper,

part I. Ultrasound Med Biol 2019;45:271-81. Crossref

5. Nicholas E, Ly AA, Prince AM, et al. The current status of

ultrasound education in United States medical schools. J

Ultrasound Med 2021;40:2459-65. Crossref

6. Feilchenfeld Z, Dornan T, Whitehead C, Kuper A.

Ultrasound in undergraduate medical education: a

systematic and critical review. Med Educ 2017;51:366-78. Crossref

7. Oteri V, Occhipinti F, Gribaudo G, Marastoni F, Chisari E.

Integration of ultrasound in medical school: effects on

physical examination skills of undergraduates. Med Sci

Educ 2020;30:417-27. Crossref

8. Hoffmann B, Blaivas M, Abramowicz J, et al. Medical

student ultrasound education, a WFUMB position paper,

part II. A consensus statement by ultrasound societies.

Med Ultrason 2020;22:220-9. Crossref

9. Asian Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine

and Biology. AFSUMB affiliated societies as of 2022.

Available from: http://www.afsumb.org/about/. Accessed 25 Jan 2024.

10. Teo LL, Choo YS, Ong CC, Han T, Chong VF, Quek ST. A

follow-up longitudinal survey on a cohort of undergraduate

medical students’ attitudes towards radiology. Ann Acad

Med Singap 2015;44:29-31. Crossref

11. Kameda T, Taniguchi N, Konno K, Koibuchi H, Omoto K,

Itoh K. Ultrasonography in undergraduate medical

education: a comprehensive review and the education

program implemented at Jichi Medical University. J Med

Ultrason (2001) 2022;49:217-30. Crossref

12. Das Gupta M. Is banning sex-selection the best approach

for reducing prenatal discrimination? Asian Popul Stud 2019;15:319-36. Crossref

13. Coiffier B, Shen PC, Lee EY, et al. Introducing point-of-care

ultrasound through structured multifaceted ultrasound

module in the undergraduate medical curriculum at The

University of Hong Kong. Ultrasound 2020;28:38-46. Crossref

14. So T, King A, Leung K, et al. The Chinese University of

Hong Kong Courseware Development Grant (2018-19)

final report. eLearning module in abdominal ultrasound.

2019. Available from: https://www.cuhk.edu.hk/eLearning/c_tnl/cdgs/2018-19/report/fr_13.pdf. Accessed 29 Oct 2022.

15. Cantisani V. The Education and Professional Standards Committee (EPSC). Ultraschall Med 2016;37:210. Crossref

16. Ho AM, Critchley LA, Leung JY, et al. Introducing final-year

medical students to pocket-sized ultrasound imaging:

teaching transthoracic echocardiography on a 2-week

anesthesia rotation. Teach Learn Med 2015;27:307-13. Crossref

17. Wang TC, Chen WT, Kang YN, et al. Why do pre-clinical

medical students learn ultrasound? Exploring

learning motivation through ERG theory. BMC Med Educ

2021;21:438. Crossref

18. Grand View Research. Ultrasound device market size,

share & trends analysis report by product (diagnostic,

therapeutic), by portability (handheld, cart/trolley), by

application, by end-use, by region, and segment forecasts,

2022-2030. Available from: https://www.marketresearch.com/Grand-View-Research-v4060/Ultrasound-Device-Size-Share-Trends-31516542/. Accessed 5 Mar 2023.

19. Stewart KA, Navarro SM, Kambala S, et al. Trends in

ultrasound use in low and middle income countries: a

systematic review. Int J MCH AIDS 2020;9:103-20. Crossref

20. EduRank. Best universities for sonography/ultrasound technician in Asia. Available from: https://edurank.org/medicine/sonography/as. Accessed 5 Mar 2023.

21. Miles N, Cowling C, Lawson C. The role of the sonographer—an investigation into the scope of practice for the sonographer internationally. Radiography (Lond)

2022;28:39-47. Crossref