Hong Kong Med J 2024 Feb;30(1):56–61 | Epub 19 Feb 2024

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PERSPECTIVE

Feasible non-surgical options for management of knee osteoarthritis during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond

JR Khoo, MB, BS1; PK Chan, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; Chunyi Wen, MB,BS, PhD (Orthopaedic Surgery)2; Lawrence CM Lau, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; Thomas KC Leung, MB, BS, FHKCOS3; Michelle Hilda Luk, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)3; Vincent WK Chan, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)3; Amy Cheung, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)3; MH Cheung, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; Henry Fu, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1; KY Chiu, FHKCOS, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)1

1 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Biomedical Engineering, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr PK Chan (cpk464@yahoo.com.hk)

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common degenerative joint

disease involving progressive deterioration of joint

cartilage and underlying bone. It most commonly

affects the distal interphalangeal, hip, and knee joints

through degeneration resulting in progressive loss of

function, increasing stiffness, and worsening pain.1

Knee OA is a common debilitating disease among

older adults. In 2018, 1.27 million (17.9%) Hong

Kong residents were aged ≥65 years; this number

is projected to double to 2.44 million by 2038.2 The

increasing ageing population and worsening obesity

epidemic are expected to greatly increase the number

of individuals with knee OA. Although early-stage

OA can be asymptomatic, subsequent joint pain

often causes healthcare-seeking behaviour.

Patients with knee OA experience rapidly

worsening pain and decreasing joint functionality

during prolonged inactivity. The social distancing

measures enforced during the coronavirus disease

2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Hong Kong have

hindered patient adherence to international OA

guidelines.3 Due to the possibility of future pandemics

and outbreaks, it is crucial that we provide patients

with practical non-surgical approaches to pain

management and minimising the risk of progression.

Considering language barriers, treatment availability,

and variations in COVID-19 regulations, locality-specific

recommendations are essential. Primary

healthcare practitioners and Hong Kong residents can

utilise the therapeutic tools described in this article to

promote self-management of knee OA in Hong Kong

throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

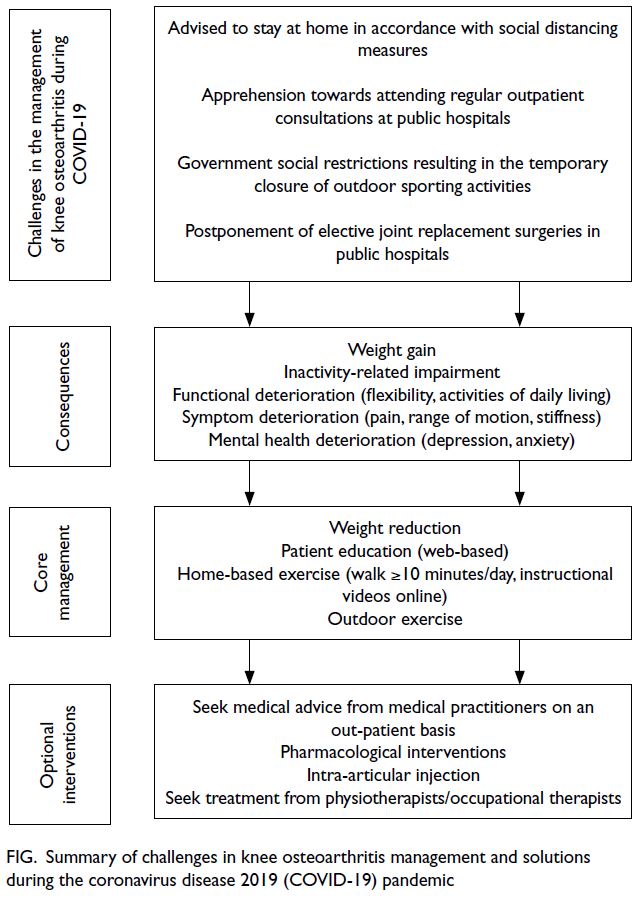

Overview of knee osteoarthritis treatment during coronavirus disease 2019

A recent analysis of COVID-19 effects on arthroplasty services in Hong Kong showed large (>50%) decreases

in elective arthroplasties and surgical volume from

January to June 2020.4 Although the rate of revision

operations remained similar during this period, the

number of primary arthroplasty operations decreased

by 91%, emphasising the importance of effective

non-surgical treatment options for knee OA.4 The

multifactorial aetiology and slow progression of knee

OA enable implementation of diverse therapeutic

regimens. Non-surgical treatments can be broadly

divided into non-pharmacological (preferred) and

pharmacological options (Fig).

Figure. Summary of challenges in knee osteoarthritis management and solutions during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic

Non-pharmacological treatments

Non-pharmacological options are the first-line

treatment for OA. Despite their high efficacy and

favourable side-effect profiles, such treatments are

often overlooked in favour of pharmacological or

surgical approaches.5 Non-pharmacological options

involve patient education, weight reduction and

exercise, physical and occupational therapy, and

orthotic assistance. Their principle outcomes include

slower disease progression, pain relief, and improved

functionality.

Education

A better understanding of knee OA and its

progression can motivate patients to assume

an active role in their treatment plan, thereby

improving compliance and promoting health-seeking

behaviours. Knowledgeable patients can

recognise relevant symptoms, reducing anxiety and

enabling clear reporting. Patient education also

limits misinformation and misconceptions. In a

qualitative study of patients with hip and knee OA

during the COVID-19 pandemic, most individuals

failed to utilise first-line interventions for OA (ie,

therapeutic exercises) despite pandemic-related

restrictions; they believed that complementary OA treatments (ie, physiotherapy) offered better

therapeutic effects than exercise.6 The Elderly

Health Service, a subsidiary of the Department of

Health of Hong Kong, has published official OA fact

sheets, instructional exercise videos, and treatment

guidelines in Cantonese, English and Mandarin,

facilitating use by the Hong Kong population, where

Cantonese is the first language.7 There are also

other web-based education programmes worldwide

(online supplementary Table 1).

Weight reduction

Knee OA is strongly associated with obesity. The

2014/15 Hong Kong Population Health Survey

revealed that approximately 50% of adults in the

general population were obese or overweight.8 A

meta-analysis9 found that obesity and overweight

increased the risk of knee OA by 35% for every

5 kg/m2 increase in body mass index. Weight

reduction can decrease the mechanical and inflammatory stressors involved in knee OA.

Treatment methods include lifestyle

modification, calorie restriction, regular physical

activity, pharmacological means, and surgical

approaches. Pandemic-related social restrictions have

hampered outdoor physical activity. Additionally,

stress-related calorie intake may increase during

lockdown. Access to outpatient dietetic services has

been limited during the pandemic, hindering patient

accountability for eating habits. In Hong Kong,

telemedicine consultations with dietitians were

more effective than face-to-face dietetic services

for promoting intermediate- and long-term weight

reduction in overweight individuals.10 There is

evidence showing the benefits of weight reduction

on pain and physical disability.11

Exercise

Exercise can help reduce body weight and strengthen

surrounding muscles. Although exercises involving

excessive joint loads should be avoided, low-impact

aerobic exercises can reduce pain, improve limb

mobility, and restore joint function.12 International

OA guidelines recommend multimodal exercise

programmes that incorporate targeted resistance

and flexibility training.3 Resistance programmes can

include resistance training machines (isokinetic)

and body weight (isotonic) exercises to strengthen

quadricep muscles, improving joint stability

and reducing pain severity. Recent COVID-19 restrictions in Hong Kong have resulted in

temporary closures of fitness centres and mandatory

mask usage during physical activity. These new

restrictions have precluded the exercise intensity

needed to improve knee OA outcomes. Nevertheless,

a randomised controlled trial showed that simple

home-based exercises led to 30% reduction in

the WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster

Universities Osteoarthritis Index) compared with

educational control and diet groups.13 A prospective

cohort study assessing the effects of the COVID-19

lockdown on hip and knee OA revealed significant

pain exacerbation (according to visual analogue scale

score) and reduced joint functionality (according

to WOMAC score for pain, stiffness, and physical

function) among individuals with decreased physical

activity.14 To prevent inactivity-related impairment,

adults with knee OA are advised to walk at least 10

minutes per day15; this goal is feasible for individuals

confined to their homes during the fifth wave of the

COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong.

Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy is important for patients with knee

OA. Full-range active and passive joint movements

can prevent contractures that limit joint function

and precede disability. Resistance training restores

periarticular muscle strength, thus improving physical function, reducing joint pain, and slowing

cartilage degeneration. The clinical effects on

knee OA include improvements in walking speed,

walking distance, timed up and go test outcomes,

and stair climbing. A community-based aquatic

exercise programme for patients with knee OA

recently demonstrated effectiveness and feasibility

in Hong Kong. Improvements in joint functionality

and quadricep strength were observed after 10

weeks of physiotherapist-led aquatic exercises.16

Although pandemic-related rehabilitation service

disruption interrupted treatment for some

patients, tele-rehabilitation usage in Hong Kong

significantly increased during the pandemic.17

Among 9101 patients utilising tele-rehabilitation,

rates of satisfaction and adherence to prescribed

rehabilitation activities were high; moreover, 1112

therapists (50.6% of the workforce) prescribed tele-rehabilitation

during the pandemic.17

Orthotics

Considering their affordability, negligible adverse

effects, and relative ease of application, braces are

ideal for Hong Kong patients with knee OA in the

COVID-19 era. The use of a soft knee brace improves

knee instability and functionality. A cohort study of

bracing and orthotics efficacy showed improvements

in pain and joint functionality among patients with

knee OA in Hong Kong after 24 weeks.18 Although

shoe insoles had a compliance rate exceeding

90%, bracing had a compliance rate of 54.5%; skin

discomfort in the hot and humid climate contributed

to poor adherence.18

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

has become a convenient option for in-home

pain relief among patients with knee OA. Retail

chains throughout Hong Kong offer affordable

stimulation devices, reducing barriers to treatment.

A recent randomised controlled trial demonstrated

considerable improvements in the visual analogue

scale score for pain and distance walked in the 6-minute walk test, following a trial of transcutaneous

electrical nerve stimulation in patients with minimal

knee pain.19

Pharmacological treatments

Pharmacological agents may be indicated for patients

with recalcitrant symptomatic knee OA. No available

pharmacological therapies for knee OA are disease-modifying;

they should only be used during symptom

worsening. A step-up approach should be utilised

regarding pharmacological treatments, with careful

and deliberate assessment of the clinical context

before administration. According to international

guidelines, paracetamol is not considered first-line firstline

treatment for knee OA because of its clinically

insignificant effects on pain management.3 However,

Hong Kong guidelines recommend paracetamol as

first-line treatment.20

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Topical and oral formulations of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs (NSAIDs) can be administered

to patients with knee OA. Under Hong Kong and

international guidelines, topical NSAIDs are strongly

recommended for the first-line management of knee

OA because of their pain management efficacy

and satisfactory safety.20 Patients with inadequate

symptom relief from topical NSAIDs may transition

to oral NSAIDs with satisfactory gastrointestinal,

cardiovascular, and renal profiles. The minimum

necessary dose of oral NSAIDs for pain control

should be used because of possible side-effects.

Patients with gastrointestinal complications

should receive a proton pump inhibitor along with

NSAIDs.21

Glucosamine and chondroitin sulphate

Glucosamine and chondroitin sulphate are

considered safe and useful conservative treatments

in oral supplement form. Both compounds have anti-inflammatory

and immunomodulatory activities that

can decrease cartilage degeneration and increase

hyaluronic acid (HA) synthesis.22 Despite strong

international recommendations against glucosamine

usage, Hong Kong guidelines support its application

in mild to moderate knee OA.20 Although active

prescribing of glucosamine and chondroitin sulphate

is discouraged, clinicians should not prohibit its use

among patients who experience clear benefits.

Opioids

Opioid administration for pain relief should be

reserved for patients with severe recalcitrant pain.

Similar to NSAIDs, the minimum necessary dosage

of opioids should be used while monitoring for

common side-effects. Opioid use is discouraged

because of negative impacts on patients and society.

The high incidences of short-term side-effects and

long-term consequences highlight the importance

of limiting opioid use.23 There is a negligible pain

reduction benefit during long-term use of opioid

medications for knee OA. The risks of opioid use

consistently outweigh the benefits of such treatment.

Clinicians should utilise alternative non-surgical

treatments in a stepwise manner.23

Topical capsaicin

Topical capsaicin is an alternative treatment

option for patients with mild recalcitrant knee OA.

Capsaicin alleviates pain by depleting substance P

and inhibiting the TRPV1 receptor on nociceptive sensory neurons. Prolonged capsaicin application

can desensitise nociceptive fibres and inhibit

pain transmission. Low-concentration capsaicin

formulations have consistently demonstrated

safety and efficacy. Nevertheless, topical NSAIDs

remain preferable as first-line treatment for knee

OA because of their favourable side-effect profile

and greater evidence of efficacy. A trial regimen of

capsaicin should be offered to patients with a poor

response (or contraindications) to topical NSAIDs.24

Injection

Intra-articular corticosteroids

Intra-articular corticosteroids are useful for

patients with symptoms recalcitrant to NSAIDs.

Although they are highly effective in reducing

short-term pain, they have poor long-term efficacy.3

Corticosteroids exhibit both anti-inflammatory and

immunosuppressive effects: after treatment, patients

typically experience improved joint mobility and

rapid reductions of erythema, swelling, heat, and

tenderness in affected joints.3 Frequent intra-articular

corticosteroid use should be avoided

because of the increased infection risk and potential

damage to joints and cartilage.

Intra-articular hyaluronic acid

Hyaluronic acid, a naturally occurring

glycosaminoglycan, increases the viscosity and

elasticity of synovial fluid, thereby facilitating

joint lubrication and reducing cartilage stress.

Additionally, HA has anti-inflammatory and

chondroprotective properties. Elevated levels of

inflammatory cytokines and proteolytic enzymes in

OA interfere with these properties and contribute to

knee joint deterioration.25 Intra-articular injection of

HA may restore viscoelasticity to synovial fluid. A

Cochrane review comparing intra-articular HA with

corticosteroids revealed no significant differences 4

weeks after administration; however, intra-articular

HA was more effective 5 to 13 weeks after injection.26

Other studies have shown that HA treatment for

moderate OA decreased the mean number of opioid

prescriptions (both existing and new), improved the

maintenance of medial and lateral joint space areas,

and delayed the need for total knee replacement

surgery.27 Although various intra-articular HA

preparations exist (online supplementary Table 2), their clinical effects remain controversial

because of conflicting data. The American College

of Rheumatology and American Academy of

Orthopaedic Surgeons do not recommend using HA

as an analgesic for OA. Although there is evidence

of HA safety and efficacy in knee OA, this expensive

treatment may be unsuitable for some patients.26

In Hong Kong, HA is recommended because it

significantly reduces pain and has an excellent safety profile. A study of hylan G-F 20 injection safety

and efficacy among patients with knee OA in Hong

Kong showed significant improvements in pain and

function over 6 months after a single 6-mL intra-articular

injection; that study also demonstrated

the feasibility of locality-wide HA use in outpatient

settings.28

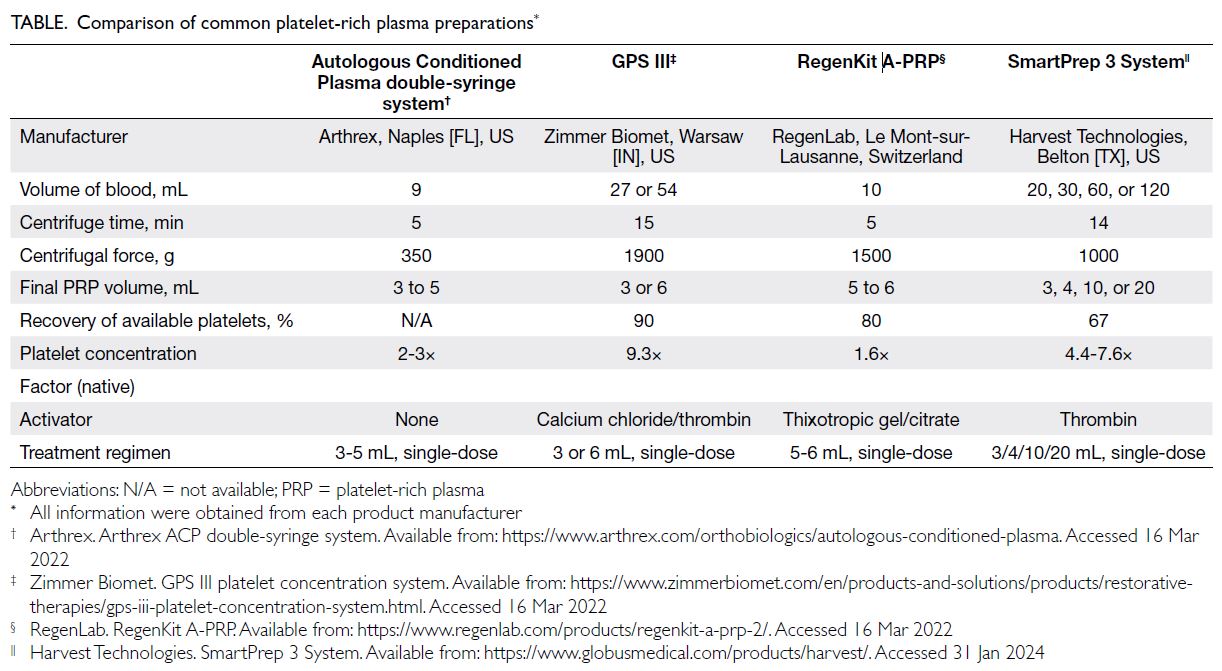

Platelet-rich plasma

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is a minimally invasive,

inexpensive method to obtain biologically active

molecules for the treatment of knee OA.29 Whereas

HA requires exogenous fermentation, PRP is

obtained by centrifugation of autologous blood.

There are four common PRP preparations (Table).

Extracted plasma can exhibit considerably higher

concentrations of platelets compared with normal

blood. The extracted platelets degranulate upon

reinjection, releasing growth factors and bioactive

molecules that promote healing at injured sites.

Improvements in chondrocyte apoptosis, cartilage

proteoglycan concentrations, and OA progression

have been observed after intra-articular injection

of PRP. Furthermore, pain relief, knee function,

and quality of life are improved, compared with

HA level.30 The Osteoarthritis Research Society

International discourages PRP usage considering the

low quality of evidence and lack of standardisation

among formulations. However, applications of PRP

persist in private clinics in Hong Kong; thus, patients

and clinicians should be knowledgeable regarding

the available formulations.

Mesenchymal stem cells

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent

progenitors that can be obtained from numerous

tissues. Although they do not have unlimited

differentiation potential, MSCs are preferred

among stem cell treatments for OA because of

their widespread availability.31 The pluripotency

of MSCs enables differentiation into osteoblasts,

chondrocytes, and adipocytes, facilitating the

recovery of knee joints with OA. Additionally, MSCs

secrete cytokines and growth factors with anti-inflammatory

and immunomodulatory properties

that can enhance cartilage regeneration, reduce

inflammation, and improve angiogenesis. Primary

isolated stromal cells constitute the best option for

knee OA treatment. Bone marrow–derived stromal

cells (from the posterior superior iliac spine) and

adipose tissue–derived stromal cells (from the

infrapatellar fat pad and subcutaneous sites) are

most commonly utilised in clinical settings.32 Despite

the promising potential of MSCs, existing evidence

has been obtained from small uncontrolled studies

with diverse cell preparation methods and short

follow-up. The optimal tissue source and cell dose

also remain unclear, hindering conclusions about the clinical effects of MSCs. Randomised controlled

trials with larger patient cohorts are needed to

confirm the safety and efficacy of MSCs in knee OA.

Exacerbation of knee pain during coronavirus disease 2019

Numerous underlying aetiologies may explain the

pronounced exacerbation of OA-related knee pain

throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Prolonged

inactivity and inadequate non-surgical management

have been associated with worsening knee pain and

joint functionality during the pandemic.14 There

have also been reports of COVID-19–related

arthritis; although its clinical presentation was

similar to knee OA, affected patients had reactive

or inflammatory arthritis that could require disease-modifying

antirheumatic drugs.33 Accordingly,

primary healthcare practitioners should make

referrals to appropriate specialists when doubt

arises.

Conclusion

Social distancing measures during the COVID-19

pandemic have hindered care for patients with knee

OA. Prolonged inactivity has been associated with

worsening symptoms, disease progression, and poor

functional outcomes. The non-surgical modalities

highlighted in this article are specifically tailored to

the Hong Kong population; they are feasible under stringent social distancing. Primary healthcare

practitioners should utilise and promote these tools

to enhance self-management and prepare patients

for future outbreaks and pandemics.

Author contributions

Concept or design: PK Chan, C Wen, LCM Lau, TKC Leung, MH Luk, VWK Chan, A Cheung, MH Cheung, H Fu, KY Chiu.

Acquisition of data: JR Khoo.

Analysis or interpretation of data: JR Khoo.

Drafting of the manuscript: JR Khoo.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: PK Chan, C Wen, LCM Lau, TKC Leung, MH Luk, VWK Chan, A Cheung, MH Cheung, KY Chiu.

Acquisition of data: JR Khoo.

Analysis or interpretation of data: JR Khoo.

Drafting of the manuscript: JR Khoo.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: PK Chan, C Wen, LCM Lau, TKC Leung, MH Luk, VWK Chan, A Cheung, MH Cheung, KY Chiu.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material was provided by the authors and some information may not have been peer reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by the Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association. The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine and the Hong Kong Medical Association disclaim all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content.

References

1. Abramoff B, Caldera FE. Osteoarthritis: pathology, diagnosis, and treatment options. Med Clin North Am 2020;104:293-311. Crossref

2. Wong K, Yeung M. Office of the Government Economist,

Hong Kong SAR Government. Population ageing trend of

Hong Kong. January 2019. Available from: https://www.hkeconomy.gov.hk/en/pdf/el/el-2019-02.pdf. Accessed 8 Mar 2022.

3. Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, et al. OARSI

guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip,

and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage

2019;27:1578-89. Crossref

4. Lee LS, Chan PK, Fung WC, et al. Lessons learnt from the

impact of COVID-19 on arthroplasty services in Hong

Kong: how to prepare for the next pandemic? Arthroplasty

2021;3:36. Crossref

5. Hussain SM, Neilly DW, Baliga S, Patil S, Meek RM. Knee

osteoarthritis: a review of management options. Scott Med

J 2016;61:7-16. Crossref

6. Battista S, Dell’Isola A, Manoni M, Englund M, Palese A,

Testa M. Experience of the COVID-19 pandemic as lived

by patients with hip and knee osteoarthritis: an Italian

qualitative study. BMJ Open 2021;11:e053194. Crossref

7. Elderly Health Service, Department of Health, Hong Kong

SAR Government. Elderly Health Service. Available from:

https://www.elderly.gov.hk/eindex.html. Accessed 8 Mar

2022.

8. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong

Kong SAR Government. Report of Population Health

Survey 2014/2015. 2017. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/dh_phs_2014_15_full_report_eng.pdf. Accessed 8 Mar 2022.

9. Zheng H, Chen C. Body mass index and risk of knee

osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of

prospective studies. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007568. Crossref

10. Chung LM, Law QP, Fong SS, Chung JW, Yuen PP. A cost-effectiveness analysis of teledietetics in short-, intermediate-, and long-term weight reduction. J Telemed Telecare 2015;21:268-75. Crossref

11. Christensen R, Bartels EM, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Effect of

weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee

osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann

Rheum Dis 2007;66:433-9. Crossref

12. Tanaka R, Ozawa J, Kito N, Moriyama H. Efficacy of

strengthening or aerobic exercise on pain relief in people

with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis

of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil

2013;27:1059-71. Crossref

13. Jenkinson CM, Doherty M, Avery AJ, et al. Effects of dietary

intervention and quadriceps strengthening exercises on

pain and function in overweight people with knee pain:

randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;339:b3170. Crossref

14. Endstrasser F, Braito M, Linser M, Spicher A, Wagner M,

Brunner A. The negative impact of the COVID-19

lockdown on pain and physical function in patients with

end-stage hip or knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports

Traumatol Arthrosc 2020;28:2435-43. Crossref

15. Jakiela JT, Waugh EJ, White DK. Walk at least 10 minutes

a day for adults with knee osteoarthritis: recommendation

for minimal activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. J

Rheumatol 2021;48:157-9. Crossref

16. Lau MC, Lam JK, Siu E, Fung CS, Li KT, Lam MW. Physiotherapist-designed aquatic exercise programme for community-dwelling elders with osteoarthritis of the knee:

a Hong Kong pilot study. Hong Kong Med J 2014;20:16-23. Crossref

17. Ku BP, Tse AW, Pang BC, et al. Tele-rehabilitation

to combat rehabilitation service disruption during

COVID-19 in Hong Kong: observational study. JMIR

Rehabil Assist Technol 2021;8:e19946. Crossref

18. Fu HC, Lie CW, Ng TP, Chen KW, Tse CY, Wong WH.

Prospective study on the effects of orthotic treatment for

medial knee osteoarthritis in Chinese patients: clinical

outcome and gait analysis. Hong Kong Med J 2015;21:98-106. Crossref

19. Shimoura K, Iijima H, Suzuki Y, Aoyama T. Immediate

effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

on pain and physical performance in individuals with

preradiographic knee osteoarthritis: a randomized

controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2019;100:300-6.e1. Crossref

20. Kan HS, Chan PK, Chiu KY, et al. Non-surgical treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Hong Kong Med J 2019;25:127-33. Crossref

21. Cao P, Li Y, Tang Y, Ding C, Hunter DJ. Pharmacotherapy

for knee osteoarthritis: current and emerging therapies.

Expert Opin Pharmacother 2020;21:797-809. Crossref

22. Simental-Mendía M, Sánchez-García A, Vilchez-Cavazos F,

Acosta-Olivo CA, Peña-Martínez VM, Simental-Mendía

LE. Effect of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate in

symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and

meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials.

Rheumatol Int 2018;38:1413-28. Crossref

23. da Costa BR, Pereira TV, Saadat P, et al. Effectiveness and

safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioid

treatment for knee and hip osteoarthritis: network meta-analysis.

BMJ 2021;375:n2321. Crossref

24. Persson MS, Stocks J, Sarmanova A, et al. Individual

responses to topical ibuprofen gel or capsaicin cream

for painful knee osteoarthritis: a series of n-of-1 trials.

Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60:2231-7. Crossref

25. Axe JM, Snyder-Mackler L, Axe MJ. The role of viscosupplementation. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2013;21:18-22. Crossref

26. Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V, Gee T, Bourne R, Wells G. Viscosupplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;2006:CD005321. Crossref

27. Bansal H, Leon J, Pont JL, et al. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP)

in osteoarthritis (OA) knee: correct dose critical for long

term clinical efficacy. Sci Rep 2021;11:3971. Crossref

28. Yan CH, Chan WL, Yuen WH, et al. Efficacy and safety of

hylan G-F 20 injection in treatment of knee osteoarthritis

in Chinese patients: results of a prospective, multicentre,

longitudinal study. Hong Kong Med J 2015;21:327-32. Crossref

29. Ayhan E, Kesmezacar H, Akgun I. Intraarticular injections

(corticosteroid, hyaluronic acid, platelet rich plasma) for

the knee osteoarthritis. World J Orthop 2014;5:351-61. Crossref

30. Wang-Saegusa A, Cugat R, Ares O, Seijas R, Cuscó X,

Garcia-Balletbó M. Infiltration of plasma rich in growth

factors for osteoarthritis of the knee short-term effects

on function and quality of life. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg

2011;131:311-7. Crossref

31. Kim C, Keating A. Cell therapy for knee osteoarthritis:

mesenchymal stromal cells. Gerontology 2019;65:294-8. Crossref

32. Cianca JC, Jayaram P. Musculoskeletal injuries and regenerative medicine in the elderly patient. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2017;28:777-94. Crossref

33. Mukarram MS, Ishaq Ghauri M, Sethar S, Afsar N, Riaz A,

Ishaq K. COVID-19: an emerging culprit of inflammatory

arthritis. Case Rep Rheumatol 2021;2021:6610340. Crossref