© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

REMINISCENCE: ARTEFACTS FROM THE HONG KONG MUSEUM OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

The Nelson’s inhaler

Rose HL Mak, FHKAM (Paediatrics)

Director, Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society

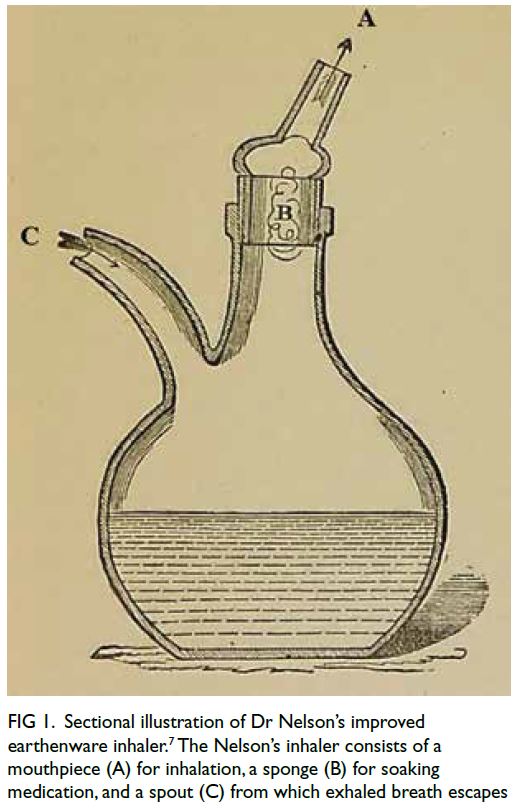

The Nelson’s inhaler is an earthenware vessel

that enables inhalation of the vapour of water and

medicinal substances (Fig 1). It was introduced on

28 May 1861 when Dr Nelson presented his recent

invention to the fellows of the Royal Medical and

Chirurgical Society of London at the conclusion

of a meeting. He drew their attention particularly

to its ‘great ease and simplicity of action, perfect

cleanliness, and an arrangement of the mouth-piece

by which is secured economy in the use of

any medicated ingredient that may be required for

inhalation’.1

Figure 1. Sectional illustration of Dr Nelson’s improved earthenware inhaler.7 The Nelson’s inhaler consists of a mouthpiece (A) for inhalation, a sponge (B) for soaking medication, and a spout (C) from which exhaled breath escapes

Respiratory ailments were rampant in Britain

at that time due to industrialisation and rapid

urban development that had occurred before the

sanitary revolution. Physicians who treated these

conditions were aware of the advantages that

inhaling medications directly into the lungs would

bring, but there was no suitable apparatus available. The demonstration of ether as an inhalational

anaesthetic in 1846 and, later, the successful use of

antiseptic heightened interest in the inhalational

administration of medication. Dr Nelson was

one of those who had spent time inventing and

experimenting with inhalation devices.

Dr John Mudge invented the first inhaler in

1778 and even coined the term. The purpose of his

invention was to provide a ‘radical and expeditious

cure for a recent catarrhous cough’ using hot water

and added herbs or medicinal products (such as

opium).2 The inhaler became popular and was used

both in hospitals and by patients at home, but those

with respiratory ailments struggled to inhale against

the pressure of the water.3 In 1865, S Maw & Son,

a prominent medical equipment manufacturer,

launched the Dr Nelson’s improved earthenware

inhaler with a notice in The Lancet. It was promoted as

a ‘very handy, cheap, simple and effective apparatus’.4

The promotional notice included the following

instructions for use: “Remove the corked stopper,

and fill the vessel half full of hot water; then pour the

remedy to be employed upon the sponge contained in

the hollow tube at B; and, having replaced the latter,

inhale the vapour through the mouth-piece at A, the

exhaled breath passing freely through the tube at C.

For the inhalation of the vapour of hot water only, or

the infusion of stramonium, hops, or other medicinal

plants, the sponge in the tube need not be displaced.”4

The new inhaler was well received by the

medical profession. In 1867, five vapour medications

(eg, vapor creasoti and vapor iodi) were incorporated

into the British Pharmacopoeia for the first time.5

In 1870, the inhaler was advertised in the British

Medical Journal as ‘a most efficient apparatus for the

inhalation of the vapour of hot water, either alone

or impregnated with ether, chloroform, henbane,

creosote, vinegar, etc., in affections of the throat and

bronchial tubes, asthma, consumption, etc.’6

The new inhaler was also well received by

patients and self-medicators. Its ‘great ease and

simplicity of action’ minimised errors when using

the device. Being earthenware, it was not liable to

corrosion and could be easily cleaned; it was also

readily available and affordable. From among the

numerous inhalers available at that time, Nelson’s was

selected to illustrate the use of an inhaler in Spencer

Thomson’s A Dictionary of Domestic Medicine and

Household Surgery.7 Over time, many different

designs of Nelson-type earthenware inhalers were produced, as witnessed by the variety collected in

many museums. The item in the collection of the

Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences bears the

logo of ‘Boots the Chemists’ and could have been

produced before the logo changed in the 1960s (Fig 2).

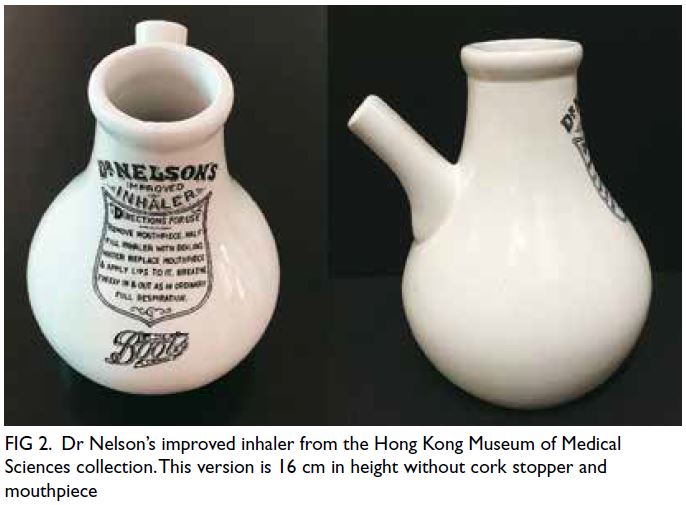

Figure 2. Dr Nelson’s improved inhaler from the Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences collection. This version is 16 cm in height without cork stopper and mouthpiece

From the mid-1900s, steam inhalers were

gradually replaced by safer and more effective drugs

(such as antibiotics, bronchodilators, steroids, and

mucolytics) and delivery systems (such as metered-dose

inhalers, dry-powder inhalers, soft mist

inhalers, and nebulisers). In Hong Kong, the Nelson’s

inhaler was used in hospitals until the 1980s (J Lui,

Senior Nursing Officer at Queen Mary Hospital from 1995 to 2007, oral communication, November

2021). Before then, tincture benzoin compound was

usually prescribed for inhalation as an expectorant.

The prepared pot would be wrapped in towels and

patients would sit in bed and inhale the vapours for 10

to 15 minutes (J Lui, oral communication, November

2021). The Nelson’s inhaler is still produced today

and is mainly used by singers to soothe their vocal

cords.

When the various inhalers were first invented,

their performance was not evaluated. While the

Nelson’s inhaler was popular, it was not specifically

referred to in case reports. Although many

advocated the use of inhaled vapours, the practice

also had its detractors.8 Williams9 concluded in

1888 that medicinal inhalations were more useful

for conditions of the pharynx, larynx and larger

bronchi but that their effects on lung parenchyma

were doubtful. He questioned whether the methods

available at the time could deliver medications

to the lungs as effectively as the oral route of

administration.9

More recently, in 2017, Murnane et al10

conducted modern inhalation performance testing

of the Nelson’s inhaler using simulated adult

breathing and a preparation of benzoic acid. They

demonstrated that about 45% of the benzoic acid

emitted from the inhaler had an aerosol size of

<6.4 μm and therefore could reach the lungs.10 This

finding could partly explain the inhaler’s enduring

popularity.

Invented 160 years ago, the Nelson’s inhaler

will be remembered as a ‘simple and effective’

apparatus that helped to establish inhalation as a

popular treatment for respiratory ailments.

References

1. Proceedings of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society of London, Volume III, Sessions 1860-61. May 28, 1861. Available from: https://books.google.ne/books?id=3fJXAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA421&hl=fr&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=2#v=onepage&q&f=false. Accessed 26 Aug 2023.

2. Cohen JS. Inhalation in the Treatment of Disease: Its Therapeutics and Practice. A Treatise on the Inhalation of Gases, Vapors, Fumes, Compressed and Rarefied Air, Nebulized Fluids, and Powders. Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston; 1876. Part I, Chapter on Inhalers, pages 19-20. Available from: https://archive.org/details/63720410R.nlm.nih.gov/mode/1up?view=theater. Accessed 26 Aug 2023.

3. Slatter EM. The evolution of anaesthesia. 2. The first English ether inhalers. Br J Anaesth 1960;32:35-45. Crossref

4. New inventions in aid of the practice of medicine and surgery. Dr. Nelson’s improved earthenware inhaler. The Lancet General Advertiser 1865;85:152.

5. General Council of Medical Education and Registration of the United Kingdom. British Pharmacopoeia, 1867. London: Spottiswoode; 1880. Available from: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/pw22vz6d/items?canvas=27&query=100. Accessed 26 Aug 2023.

6. Dr Nelson’s Improved Earthenware Inhaler (advertisement). Br Med J 1870;2:(520):Back Matter.

7. Thomson S. A Dictionary of Domestic Medicine and Household Surgery. 32nd ed. London: Charles Griffin & Company Limited; 1897: 354. Available from: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/etx3jv42/items?canvas=373&query=inhaler. Accessed 26 Aug 2023.

8. Hassall AH. On inhalation, more particularly antiseptic inhalation, in diseases of the lungs. Br Med J 1883;2:869-71.

9. Williams CT. The value of inhalations in the treatment of lung disease. Br Med J 1888;2:700-3. Crossref

10. Murnane B, Gallagher CT, Snell N, Sanders M, Moshksar R, Murnane D. Dispersing the mists: an experimental history of medicine study into the quality of volatile inhalations. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2017;30:157-63. Crossref