Hong Kong Med J 2023 Oct;29(5):448–52 | Epub 15 Sep 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

PERSPECTIVE

Hong Kong Academy of Medicine position paper on postgraduate medical education 2023

HY So, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology)1; Philip KT Li, FHKAM (Medicine)2; Paul BS Lai, FHKAM (Surgery)3; Alexander CL Chan, FHKAM (Pathology)4; Karen KL Chan, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)5; TM Chan, FHKAM (Medicine)6; David VK Chao, FHKAM (Family Medicine)7; SN Chiu, FHKAM (Psychiatry)8; KM Chu, FHKAM (Surgery)9;

KY Ho, FHKAM (Dental Surgery)10; Hugh Simon HS Lam, FHKAM (Paediatrics)11; CK Law, FHKAM (Radiology)12; SW Law, FHKAM (Orthopaedic Surgery)13; CM Ngai, FHKAM (Otorhinolaryngology)14; FC Pang, FHKAM (Community Medicine)15; Clement CY Tham, FCOphthHK, FHKAM (Ophthalmology)16; Clara WY Wu, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)17; Gilberto KK Leung, FHKAM (Surgery)18

1 Educationist, Hong Kong Academy of Medicine / President, The Hong Kong College of Anaesthesiologists, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Vice-President (Education and Examinations), Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Immediate Past Vice-President (Education and Examinations), Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 President, The Hong Kong College of Pathologists, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 President, The Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Hong Kong SAR, China

6 President, Hong Kong College of Physicians, Hong Kong SAR, China

7 President, The Hong Kong College of Family Physicians, Hong Kong SAR, China

8 President, The Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists, Hong Kong SAR, China

9 President, The College of Surgeons of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

10 President, The College of Dental Surgeons of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

11 President, Hong Kong College of Paediatricians, Hong Kong SAR, China

12 President, Hong Kong College of Radiologists, Hong Kong SAR, China

13 President, The Hong Kong College of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Hong Kong SAR, China

14 President, The Hong Kong College of Otorhinolaryngologists, Hong Kong SAR, China

15 President, Hong Kong College of Community Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

16 Immediate Past President, The College of Ophthalmologists of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

17 President, Hong Kong College of Emergency Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

18 President, Hong Kong Academy of Medicine, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof Gilberto KK Leung (gilberto@hku.hk)

Introduction

The Hong Kong Academy of Medicine (HKAM)

is committed to promoting the development of

postgraduate medical education (PGME) and

continuing medical education (CME). In 2010,

HKAM published a position paper outlining the

necessary reforms to modernise PGME.1 Progress

has been made in areas such as defining core

competencies, incorporating communication skills

into specialist training, standardising training

programmes, and implementing comprehensive

assessments. An Education Office, operated by The

Hong Kong Jockey Club Innovative Learning Centre

for Medicine, has been established under the HKAM

Education Committee to support the development

of PGME.

As HKAM celebrates its 30th Anniversary,

we aim to build upon the foundation established

in the 2010 Position Statement by embracing

new opportunities and adapting to the evolving

professional landscapes of medical education

and healthcare delivery.2 In light of this, HKAM

organised the Tripartite Medical Education

Conference (MEC) 2023 and the Strategic Planning Retreat on Education and Training 2023 to evaluate

existing frameworks and formulate actions for the

future.

The Tripartite MEC 2023, themed ‘Actualising

the Curriculum Continuum’, brought together

local and international medical experts to share

experiences and insights on optimal alignment of

postgraduate and undergraduate education. In the

roundtable discussion on 14 January 2023, titled ‘Ten

Years Down the Line’, four distinguished speakers

discussed critical topics including the challenges

faced by young doctors; the importance of quality

assurance, role modelling, and demographic

shifts; the need for trust in the healthcare system;

the impacts of technology and data sciences on

healthcare delivery; the concept of mandatory

teaching skills instruction for trainees; and the

importance of resilience and well-being among

young doctors.3

The Strategic Planning Retreat on Education

and Training, held on 4 March 2023, aimed to

establish directions for HKAM in terms of fulfilling

its fundamental responsibilities and functions within

PGME and CME.

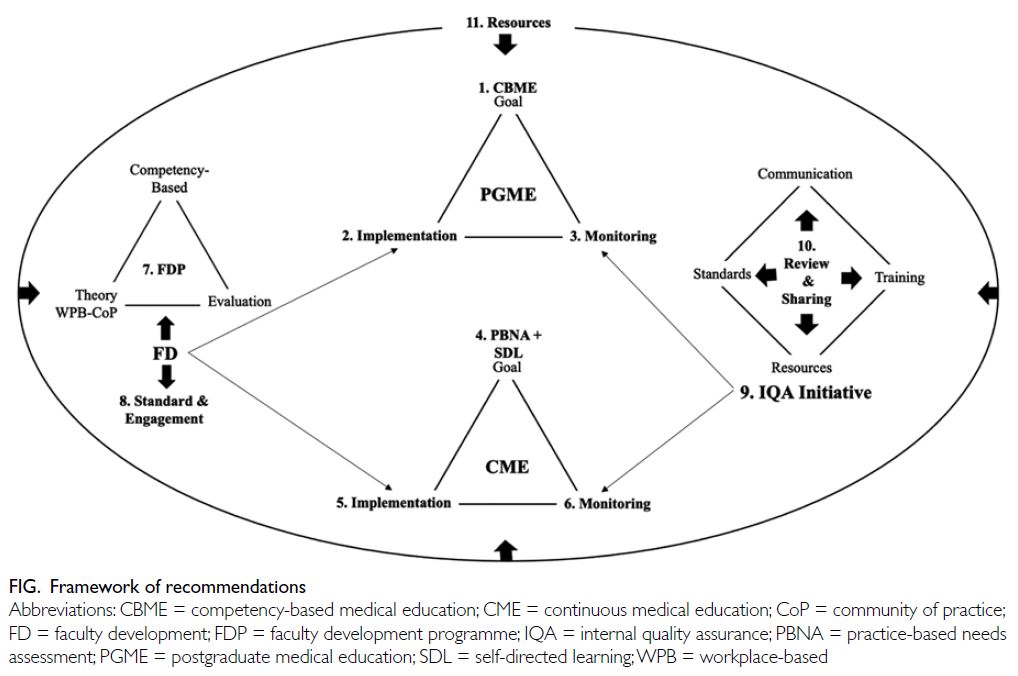

This position paper represents an update and

extension of the 2010 Position Statement based

on discussions arising from the Tripartite MEC

2023, the results of a survey conducted before

and discussed during the Retreat, and relevant

literature.4 The Figure illustrates the framework of

the recommendations made in this position paper.

Postgraduate medical education

Postgraduate medical education traditionally focused

on clinical competency alone. However, there is

increasing recognition that modern professional

training must prepare doctors to adapt to rapid

advancements in medicine, understand patient

perspectives, appreciate other professionals’ skills,

and work effectively in teams.2 5 Therefore, training

for ‘Hong Kong’s Specialist’ must encompass the

seven domains of competencies defined by HKAM.1

Postgraduate medical education has

traditionally been time-based, but there are

compelling reasons to move towards competency-based

medical education (CBME),6 which focuses on specialists’ abilities and organises competencies

based on societal and patient needs.2 While the 2010 Position Statement recommended a combination

of competency-based and time-based training,

the current view is that time should be regarded

as a resource for learning, rather than the basis for

competency progression.2 5 Therefore, instead of a

combination of time-based and CBME approaches,the focus should be on advancing towards CBME as the primary approach.

Recommendation 1: Colleges should continue to advance specialist training towards CBME.

Advancement towards CBME presents

challenges that can be addressed through four key

strategies.5 7 First, CBME is a complicated concept

that significantly differs from current practice.

Effective communication with stakeholders is

essential to engage them in this resource-intensive

change. Second, CBME requires trainers to master

teaching skills that may not be well-known. Faculty

development programmes (FDPs) are crucial. Third,

the alignment of learning and assessment methods

with CBME approaches requires educational

standards and procedures to be redesigned. Finally,

PGME is a relatively new discipline with limited

academic presence. Knowledge specific to our context

should be generated to guide implementation.2

Recommendation 2: HKAM and the Colleges should undertake the following actions to implement CBME.

(1) develop and implement a comprehensive

communication plan through appropriate channels

to effectively engage with each stakeholder segment;

(2) design and deliver FDPs that empower Fellows to

master the teaching and facilitation skills required

for CBME; (3) redesign training and assessment standards and procedures to align with the principles

and approaches of CBME; and (4) support and

participate in research activities that advance the field

of PGME and generate evidence concerning CBME

benefits that can be used to engage stakeholders.

Competency-based medical education is

a constantly evolving approach that focuses on

achieving better healthcare through effective medical

education.6 Regular evaluations are necessary to ensure progress and continuous improvement.

Recommendation 3: HKAM and the Colleges should establish a mechanism to regularly evaluate

CBME implementation and impact. A timeline for

this process should be implemented and external

reviewer involvement should be considered.

Continuing medical education/continuous professional development

Because our profession is constantly advancing,

specialists must engage in lifelong learning, known

as continuing medical education/continuous

professional development (CME/CPD).8 The

Institute of Medicine states that effective CME/CPD

should prepare healthcare professionals to provide

patient-centred care, work in teams, use evidence-based

practice, apply quality improvement, and

utilise health informatics.9 However, current CME

practices, which mainly involve didactic activities

that are not always related to patient outcomes,

have demonstrated limited impacts on physician

practice.8 Thus, there is a need for transformation.

Continuing medical education/continuous

professional development can improve performance

and patient outcomes if it is driven by practice-based

needs assessment, is ongoing, uses interactive

learning methods, and is contextually relevant.10

Recommendation 4: HKAM and the Colleges should promote lifelong learning driven by practice-based

needs assessment and self-directed learning.

The transformation of CME/CPD faces several

challenges. First, stakeholders are unfamiliar with

the new paradigm; effective communication is

essential to engage them. Second, many learners

currently view CME/CPD as a mere requirement

for specialist registration rather than an opportunity

for lifelong learning. This motivational problem

requires both engagement efforts and changes in

the CME system. Third, there is a need to empower

Fellows and CME/CPD providers to use methods

that support adult learning, and online learning is

a particularly promising method for this learning.11

Finally, many learners lack the skills and personal

attributes needed for self-directed learning; they

require support to acquire these abilities.12

Recommendation 5: HKAM and the Colleges should undertake actions to transform CME/CPD, including:

(1) devise and deliver a comprehensive

communication plan to effectively engage all

stakeholders; (2) reform the structure and redesign

the standards and procedures of CME requirements

and accreditation to align with the new CME

paradigm; (3) design and implement FDPs to

empower Fellows and possibly other CME providers

to use learning methods which support adult learning;

(4) nurture the capacities of learners to practise self-directed

learning; (5) support the development of

online learning through the provision of technology

and relevant training in educational practices; and

(6) establish partnerships with overseas CME/CPD

accreditation bodies.

The process of transforming CME/CPD will

be a long journey that requires regular evaluation to

ensure forward movement in the correct direction.

Recommendation 6: HKAM and the Colleges should establish a mechanism and regularly

evaluate the progress of CME transformation.

Faculty development

The development of PGME and CME relies on

clinical educators who are equipped with modern

medical education knowledge and skills. This

reliance highlights the critical need for faculty

development.13

A generic FDP that can be adapted to meet

specific needs of each College would be beneficial.

The objectives of the generic FDP should not be

limited to teaching skills; they should also focus

on motivating Fellows to participate in education,

emphasise professional identity, and build leadership

skills for Fellows with leading roles.14 15 The generic

FDP should be competency-based, be driven by

sound education theories, promote workplace

learning, foster the development of communities

of practice, and be evaluated for continuous

improvement.13 14 15

Recommendation 7: HKAM and the Colleges should enhance teaching skills, motivate

participation in educational activities, and

strengthen leadership in medical education through

the introduction of FDPs.

The Academy should create competency-based

curricula for FDPs that can be implemented

for clinical teachers at various levels, according to

their respective roles and responsibilities. Faculty

development programmes should comprise

induction courses or workshops based on theories

of situated learning, experiential learning, and adult

learning. Additionally, opportunities for workplace learning and mutual learning should be provided

through communities of practice involving clinical

educators. Moreover, HKAM and the Colleges

should establish mechanisms to evaluate FDPs using

both quantitative and qualitative methods.

The statuses of trainers should be enhanced

to engage Fellows in teaching activities. The

Academy should establish a benchmark, which

can be customised by each College, for trainer

accreditation and define trainers’ expected teaching

responsibilities. Additionally, HKAM and the

Colleges should explore ways to acknowledge

Fellows’ contributions to education. For example,

training activities should be eligible for credit

towards CME/CPD.

Recommendation 8: HKAM and the Colleges should develop a set of guidelines for trainers, a

system for certifying trainers, and strategies to

cultivate a distinguished image of clinical educators.

Quality assurance

As providers of PGME and CME, HKAM and

the Colleges are responsible for ensuring quality

and must be accountable for the training they

provide.16 However, quality assurance is not widely

regarded as a priority; greater communication and

encouragement are needed.

We focus on internal quality assurance (IQA),

which involves implementing activities and processes

that control, monitor, improve, and enhance

educational quality.17 The IQA cycle consists of three

steps: defining measurement parameters, judging

quality based on collected data, and taking actions

for improvement.17

The World Federation for Medical Education

has defined standards in eight areas for PGME,18

two of which were highlighted during the Retreat:

trainer quality and assessments. Evaluation of the

psychometric properties of assessments can be

supported by psychometricians and appropriate

software; training is necessary to interpret findings.

Qualitative methods are often used to collect

valuable data for improvement purposes. However,

Fellows may require training to become familiar

with these methods.

Next, criteria and standards can be established

to interpret the collected data and assess the quality

of education.17 Finally, actions taken for improvement

require the assignment of responsibility as well as the

development of a culture of continuous improvement

and a sense of ownership and commitment among

learners and staff.17 19

Recommendation 9: HKAM and Colleges should implement a structured quality assurance initiative

by taking the following steps:

(1) develop and execute a comprehensive

communication strategy that reaches each

stakeholder segment through appropriate channels;

(2) establish quality assurance standards; (3) provide

training to Fellows responsible for quality assurance

on quality assurance fundamentals, standard

establishment, quality metric interpretation, and

qualitative evaluation methods; and (4) allocate

resources to facilitate quality assurance initiatives.

Recommendation 10: HKAM and Colleges should create a mechanism for Colleges to regularly review

and share their experiences in quality assurance and improvement activities.

For IQA to yield helpful results, the assessment

tasks must be integrated into the Colleges’ daily

operations and executed in an organised and

structured manner.20 The Academy and the Colleges

should scrutinise their quality assurance procedures

to ensure compliance with these conditions.

Recommendation 11: HKAM should liaise with the Government, the Hospital Authority, and other

funding sources to secure resources that support

advancement towards CBME, transformation

of CME/CPD, faculty development, and quality

assurance. HKAM should work in partnership with

the Hospital Authority to identify training needs

for the whole territory, rather than the Hospital

Authority alone.

Successful implementation of the above 11

recommendations will require significant resource

investment. Both Fellows and doctors in training will

need to devote considerable time and effort towards

these aspirations. However, because of staffing

limitations and heavy clinical workload, it may be

challenging to assign the necessary personnel and

accomplish the recommended actions. The Academy

must liaise with the Government and the Hospital

Authority to obtain their support.

There are also needs for other resources

such as medical education expertise, information

technology, and secretarial assistance. Considering

the staffing limitations, it is essential to explore

the possibility of utilising technology. E-learning

can be developed that allows trainers to focus on

workplace-based learning activities rather than

information transmission. In addition, the Academy

should seek potential funding resources to support

these initiatives.

Conclusion

The recommendations expressed in this position

paper are the products of intense deliberations

involving all Colleges and the Education Office of

HKAM, as well as leaders from the two medical

schools and the Hospital Authority. The progressive implementation of these recommendations is

expected to provide an evidence-based and effective

framework of postgraduate training in the context

of new opportunities and challenges arising from

changes in professional landscapes, healthcare

delivery models, and societal needs.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting of the

manuscript, and critical revision for important intellectual

content of the manuscript. All authors had full access to the

data, contributed to the study, approved the final version

for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and

integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the following individuals and parties for their contributions to the article:

- Prof Francis KL Chan, Dean, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong (for participation in Tripartite Medical Education Conference [MEC] 2023: roundtable);

- Dr Pamela PW Lee, Assistant Dean (Clinical Curriculum), Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong (for participation in Tripartite MEC 2023: roundtable);

- Dr Tony PS Ko, Chief Executive of the Hospital Authority (for participation in Tripartite MEC 2023: roundtable);

- Education Office, Hong Kong Academy of Medicine [HKAM] (for conducting survey and preparing the Strategic Planning and Retreat on Education and Training 2023 and Tripartite MEC 2023);

- Secretariat, HKAM (for conducting survey and preparing the Strategic Planning and Retreat on Education and Training 2023 and Tripartite MEC 2023); and

- Mr Johnson ST Lo, Chief Innovative Learning Officer, HKAM (for preparing manuscripts).

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. Position paper on postgraduate medical education. 2010. Available from:

https://www.hkam.org.hk/sites/default/files/HKAM_position_paper.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2023.

2. So HY. Postgraduate medical education: see one, do one, teach one…and what else? Hong Kong Med J 2023;29:104.e1-

9. Crossref

3. Lai PB, Wong GT, Wong SY. ‘Ten Years Down the Line’: a roundtable on the progress and advancement of medical education and training. Hong Kong Med J 2023;29:195-7. Crossref

4. Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. Summary report of Strategic Planning Retreat on Education and Training

held on 4 March 2023. 2023. Available from: https://online.hkam.org.hk/lms/retreat2023/Report-on-Strategic-Planning-Retreat-with-appendixes.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2023.

5. Frank JR, Danoff D. The CanMEDS initiative: implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Med Teach 2007;29:642-7. Crossref

6. Holmboe ES, Sherbino J, Englander R, Snell L, Frank JR; ICBME Collaborators. A call to action: the controversy of

and rationale for competency-based medical education.

Med Teach 2017;39:574-81. Crossref

7. Caverzagie KJ, Nousiainen MT, Ferguson PC, et al. Overarching challenges to the implementation of competency-based medical education. Med Teach 2017;39:588-93. Crossref

8. Stevenson R. Learning and Behaviour in Medicine: A Voyage Around CME and CPD. London, England: CRC Press; 2022. Crossref

9. Institute of Medicine Committee on Planning a Continuing Health Professional Education Institute. Redesigning Continuing Education in The Health Professions. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

10. Cervero RM, Gaines JK. The impact of CME on physician performance and patient health outcomes: an updated synthesis of systematic reviews. J Cont Educ Health Prof 2015;35:131-8. Crossref

11. Gerstein J. Moving from education 1.0 through education 2.0 towards education 3.0. In: Hase S, Kenyon C, editors. Self-Determined Learning: Heutagogy in Action. London, England: Bloomsbury Academic; 2015: 83-98.

12. Sawatsky AP, Ratelle JT, Bonnes SL, Egginton JS, Beckman TJ. A model of self-directed learning in internal

medicine residency: a qualitative study using grounded

theory. BMC Med Educ 2017;17:31. Crossref

13. Steinert Y. Faculty development: core concepts and principles. In: Steinert Y. Faculty Development in the

Health Professions: A Focus on Research and Practice.

Dordrecht: Springer; 2013: 3-25. Crossref

14. Steinert Y, Naismith L, Mann K. Faculty development initiatives designed to promote leadership in medical education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 19. Med Teach 2012;34:483-503. Crossref

15. Steinert Y. Developing medical educators: a journey, not a

destination. In: Swanwick T, Forrest K, O’Brien BC, editors.

Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory, and

Practice, Third Edition. The Association for the Study of

Medical Education (ASME); 2019: 531-48. Crossref

16. Vroeijenstijn AI. Quality assurance in medical education. Acad Med 1995;70(7 Suppl):S59-67; discussion S68-9. Crossref

17. Stalmeijer R, Dolmans D, van Berkel H, Wolfhagen I. Quality assurance. In: van Berkel H, Scherpbier A, Hillen

H. editors. Lessons from Problem Based Learning. Oxford,

United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2010: 157-66. Crossref

18. World Federation for Medical Education. WFME Global Standards for Quality Improvement in PGME. 2023.

Available from: https://www.webfepafem-pafams.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/WFME-Standards-for-PGME-2023.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2023.

19. Stalmeijer RE, Whittingham JR, Bendermacher GW, Wolfhagen IH, Dolmans DH, Sehlbach C. Continuous enhancement of educational quality—fostering a quality culture: AMEE Guide No. 147. Med Teach 2023;45:6-16. Crossref

20. Dolmans DH, Wolfhagen HA, Scherpbier AJ. From quality assurance to total quality management: how can quality assurance result in continuous improvement in health professions education? Educ Health (Abingdon) 2003;16:210-7. Crossref