Hong Kong Med J 2023 Oct;29(5):404–11 | Epub 12 Oct 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

User perceptions of COVID-19 telemedicine testing services, disease risk, and pandemic preparedness: findings from a private clinic in Hong Kong

Kevin KC Hung, FHKCEM, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)1,2,3; Emily YY Chan, MD1,2,3,4; Eugene SK Lo, MPH2,3; Zhe Huang, MPH2,3; Justin CY Wu, MD3,5; Colin Alexander Graham, MD1,2,3

1 Accident and Emergency Medicine Academic Unit, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Collaborating Centre for Oxford University and CUHK for Disaster and

Medical Humanitarian Response, The Chinese University of Hong Kong,

Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

5 CUHK Medical Centre, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof Emily YY Chan (emily.chan@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: During the coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) pandemic, telemedicine has been

regarded as a method for providing safe access to

healthcare. Here, we explored the experiences of

individuals using telemedicine in Hong Kong during

the COVID-19 pandemic to understand their risk

perceptions and preparedness measures.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional online

survey of telemedicine users of private clinic–based COVID-19 testing services from 6 April to

11 May 2020. All users were invited to complete an

anonymous online survey regarding COVID-19 risk

perception and preparedness measures. The results

of the survey were compared with the findings of a

previous territory-wide survey.

Results: In total, 141 of 187 telemedicine users

agreed to participate; the response rate was 75.4%.

Of the participants, 95.1% (116/122) believed that

telemedicine consultations were useful. Nearly half

of the participants (49.0%) agreed or strongly agreed

that telemedicine consultations were appropriate

during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most participants

believed that telemedicine consultations could

perform the functions of ‘health protection,

promotion and disease prevention’ (73.6%) and

‘diagnosis’ (64.0%). Concerning the choice of

telemedicine provider, almost all participants (99.2%) were willing to consult medical doctors;

more than half of the participants (54.1%) were

willing to consult registered nurses, but only 13.1%

were willing to consult non-clinical staff who had

been trained to provide telemedicine services.

Conclusions: The use of telemedicine for screening

and patient education can be encouraged during the

COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong.

New knowledge added by this study

- Telemedicine use in Hong Kong was limited before the pandemic, but telemedicine users had high satisfaction with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) testing services.

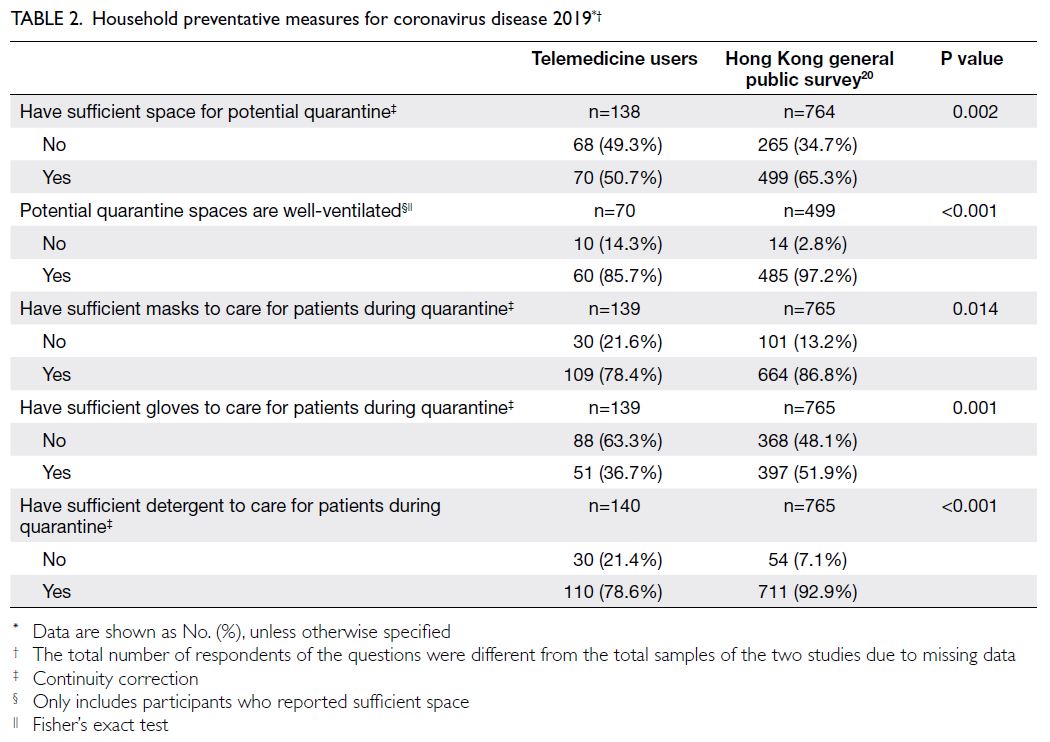

- Most participants believed that the telemedicine consultations could perform the functions of ‘health protection, promotion and disease prevention’ and ‘diagnosis’.

- Among telemedicine users, the preferred channels of infectious disease information were the internet or mobile applications as well as personal sources (eg, family, friends, or healthcare professionals).

- Telemedicine users in this study were relatively young; previous reports suggest that these users are less likely to use healthcare in the absence of telemedicine and less likely to have a follow-up visit in any setting, compared with patients who visit a clinic for a similar condition. The use of telemedicine services might provide opportunities for healthcare access that are not otherwise available.

- Additional training for telemedicine providers might be needed to improve the quality and scope of telemedicine services.

- The use of telemedicine for screening and patient education can be encouraged during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong and elsewhere.

Introduction

In the early days of the coronavirus disease

2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, telemedicine was

recommended as a solution to provide safe

access to healthcare.1 In 2020, the World Health

Organization reported that most global health

authorities regarded telemedicine as a potential

method to provide services for patients with

non-communicable diseases.2 For example, in a

national survey of healthcare providers in Germany,

approximately 60% of participants reported routine

or partial use of telemedicine during the COVID-19

pandemic.3 In the US in 2020, telemedicine was used

for COVID-19 screening, monitoring of patients

with positive COVID-19 test results, management of

chronic diseases, and virtual monitoring and follow-up.4 Telemedicine reduces patient travel costs and

improves access, while reducing the use of personal

protective equipment and the risk of COVID-19

transmission. In China, ‘internet hospitals’ offered

essential medical support to the public during the

early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.5

However, from a patient perspective, there are

limitations and barriers to the use of telemedicine. A

qualitative study conducted in Hong Kong in 20166

revealed that patient concerns included technical

and logistical issues (eg, difficulty in accessing and

using computers), limited personal interactions (eg, lack of in-person physical examinations and risk of

incorrect diagnosis related to poor communication),

concerns regarding cybersecurity and safety, and

problems with prescriptions (eg, distrust of local

community pharmacies). In 2020, clinical guidelines

were published concerning the performance of

remote primary care assessments and treatments

for patients with suspected COVID-19 in the United

Kingdom.7 During the COVID-19 pandemic, a

digital health ecosystem may benefit the healthcare

system, as well as the broader population (eg,

through tracking and communication strategies) and

research and health technology sectors (eg, online

activity monitoring and digital support for isolation

and quarantine situations).8

Telemedicine consists of remote healthcare

service delivery by healthcare professionals for

diagnosis, treatment, and prevention efforts, as

well as research and continuing education.9 The

fundamental goal of telemedicine is to increase

access to care, thereby serving populations that

otherwise would not receive timely medical

evaluation and treatment. Research concerning

telemedicine effectiveness has been controversial.10 11 12 13 14

A previous systematic review found that many

studies showed no difference between telemedicine

and usual care, and there remains limited evidence

concerning the cost-effectiveness of telemedicine.10

With respect to chronic disease management via

telemedicine, another review found publication

bias and a tendency to report only short-term

outcomes.11 Moreover, a Cochrane review revealed

improved control of blood glucose among patients

with diabetes using telemedicine, compared with

patients receiving in-person care; conversely, the

care modality did not affect health outcomes among

patients with heart failure.12 Regarding the impacts

and costs of telemedicine services, economic

analyses have been problematic because of complex

and unpredictable collaborative achievement

processes13; generalisability has been limited by poor

quality and low reporting standards.14 There is a need

to focus on patient perspectives and telemedicine

innovations.

In 2020, the health system in Hong Kong

was considerably impacted by COVID-19

transmission risk and public health responses.15

During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic,

the number of in-person medical consultations

decreased worldwide.16 17 In the Netherlands, the

use of telemedicine offset this decrease.17 Before

the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine was not

widely used in Hong Kong6 18; user perspectives

concerning the role of telemedicine during the

COVID-19 pandemic and future pandemics

require investigation. This study of telemedicine

users in Hong Kong explored their perceptions of

telemedicine use during the COVID-19 pandemic, their perceptions of disease risk, and their COVID-19

preparedness measures. We hypothesised that

telemedicine users have distinct perceptions of

risk, compared with the general public; we sought

to determine the effects of such differences on the

delivery of health services.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional online survey from 6

April to 11 May 2020. Participants in this study were

users of COVID-19 testing services provided by The

Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) Medical

Clinic,19 a multispecialty clinic offering specialist

consultations, health screenings, vaccinations, and

COVID-19 testing services.

Testing services and recruitment procedure

All service users completed a telemedicine

consultation, followed by COVID-19 testing. The

consultation, delivered using a standard telephone,

focused on assessment of the user’s COVID-19 risk

prior to the time of testing. Users were offered a deep

throat saliva test for COVID-19 detection. After the

telemedicine consultation and COVID-19 test, all

users were invited to complete an anonymous online

survey within 1 month for service evaluation and

data collection.

Survey design

The online survey consisted of 24 questions

regarding telemedicine services, COVID-19 risk

perception, and preparedness measures in Hong

Kong. The survey specifically focused on reasons for

using CUHK telemedicine and testing services, user

perceptions and attitudes regarding telemedicine

consultations, user perceptions and attitudes

regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and prevention,

and user characteristics (eg, age and sex). Questions

about user perceptions and attitudes regarding the

current COVID-19 pandemic and prevention were

phrased in a manner identical to a previous study,20

allowing direct comparison with survey results

from a study focused on the Hong Kong general

public. The survey was pilot tested and subsequently

modified to ensure content validity. Most questions

included ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers and a 5-point Likert

scale. Written consent to take part in the study was

obtained from all participants before they began the

survey.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported for participant

characteristics, perceptions, and attitudes regarding

telemedicine consultations. Perceptions and

attitudes regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and

prevention were recorded in a manner that allowed

comparison with the results of a prior COVID-19–focused telephone survey of the Hong Kong general

public.20 The prior telephone survey—a cross-sectional,

population-based landline telephone

survey using a computerised random-digit dialling

method—included 765 adult Hong Kong residents

during the period from 22 March to 1 April 2020.

The participants in that study were representative

of Hong Kong Census population data with respect

to age, sex, marital status, and residential district,

although they had higher levels of education and

household income.20 Chi squared tests were used

for comparisons between the prior survey and

the present survey. The threshold of statistical

significance was set at 0.05. All statistical analyses

were conducted using SPSS (Windows version 21.0;

IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US).

Results

Among 187 telemedicine users of COVID-19

testing services at the CUHK Medical Clinic, we

identified 150 responses to the online survey during

the period from 6 April to 11 May 2020. In total,

141 telemedicine users (response rate of 75.4%)

were willing to participate in this study. Table 1

shows the participants’ characteristics. Notably,

56.1% were men, over half (50.7%) were aged 18 to 24 years (all participants were aged <65 years),

most (59.4%) lived in private housing, and most

(65.4%) resided in the New Territories. The most

common reason for COVID-19 testing was a work-related

requirement (56.7%, 80/141), followed by

recent international travel (39.7%, 56/141); 14.9%

(21/141) of the participants sought testing because

of concerns about the spread of COVID-19. Overall,

14.2% (20/141) of the participants had either been

in close contact with a confirmed case or suspected

that they had symptoms of COVID-19.

Perceptions of telemedicine consultations

In total, 95.1% (116/122) participants believed

that COVID-19 telemedicine consultations were

useful. Most participants believed that telemedicine

consultations could perform the functions of ‘health

protection, promotion and disease prevention’

(73.6%) and ‘diagnosis’ (64.0%) [Fig 1]. Concerning

the choice of telemedicine provider, almost all

participants (99.2%) would accept medical doctors;

more than half of the participants (54.1%) would

accept trained nurses, but only 13.1% would accept

non-clinical staff who had been trained to provide

telemedicine services.

Figure 1. Functions that survey participants believed telemedicine consultations could perform (n=125)

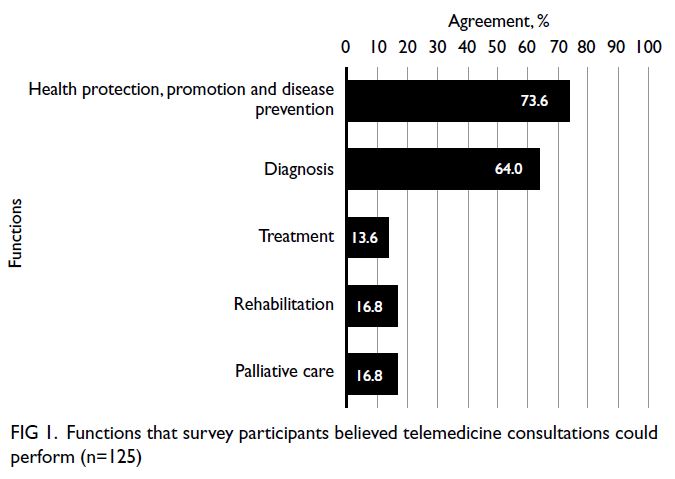

Nearly half of the participants (49.0%) agreed or

strongly agreed that telemedicine consultations were

appropriate during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig 2).

More than half (61.0%) of the participants reported

satisfaction with telemedicine consultations (‘agree’

or ‘strongly agree’) and services provided by clinic

staff (73.8% responded ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’).

However, only 36.2% agreed or strongly agreed that

service quality was identical between telemedicine

consultations and in-person consultations.

Figure 2. Participant responses concerning whether telemedicine consultations were appropriate during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (n=141)

Household capacity for potential coronavirus

disease 2019–related quarantine

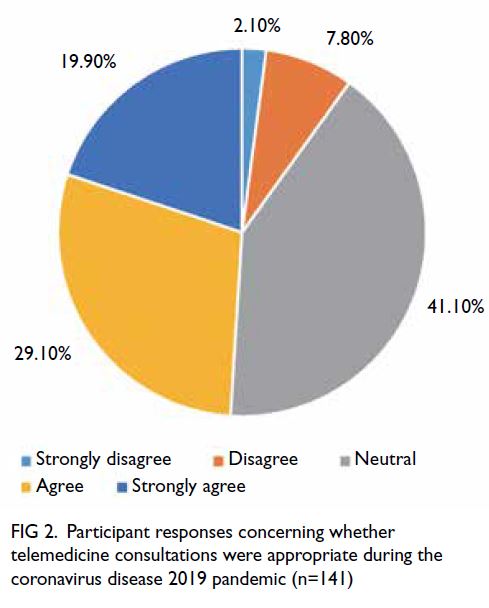

Household capacities for potential COVID-19—related quarantine were compared between

telemedicine users in this study and respondents

in the prior Hong Kong general public telephone

survey20 (Table 2). Telemedicine users reported

having less space at home, fewer masks, fewer

gloves, and less detergent for potential quarantine

situations, compared with respondents in the Hong

Kong general public telephone survey (all P<0.05).

In response to the question ‘How many

designated caregivers are appropriate for each

isolated/quarantined person?’, telemedicine users

were less likely to answer correctly (limit to one

main carer, 8.1%), compared with respondents in

the Hong Kong general public telephone survey

(51.3%)20 [P<0.001, Chi squared with continuity correction].

Perceptions of coronavirus disease 2019

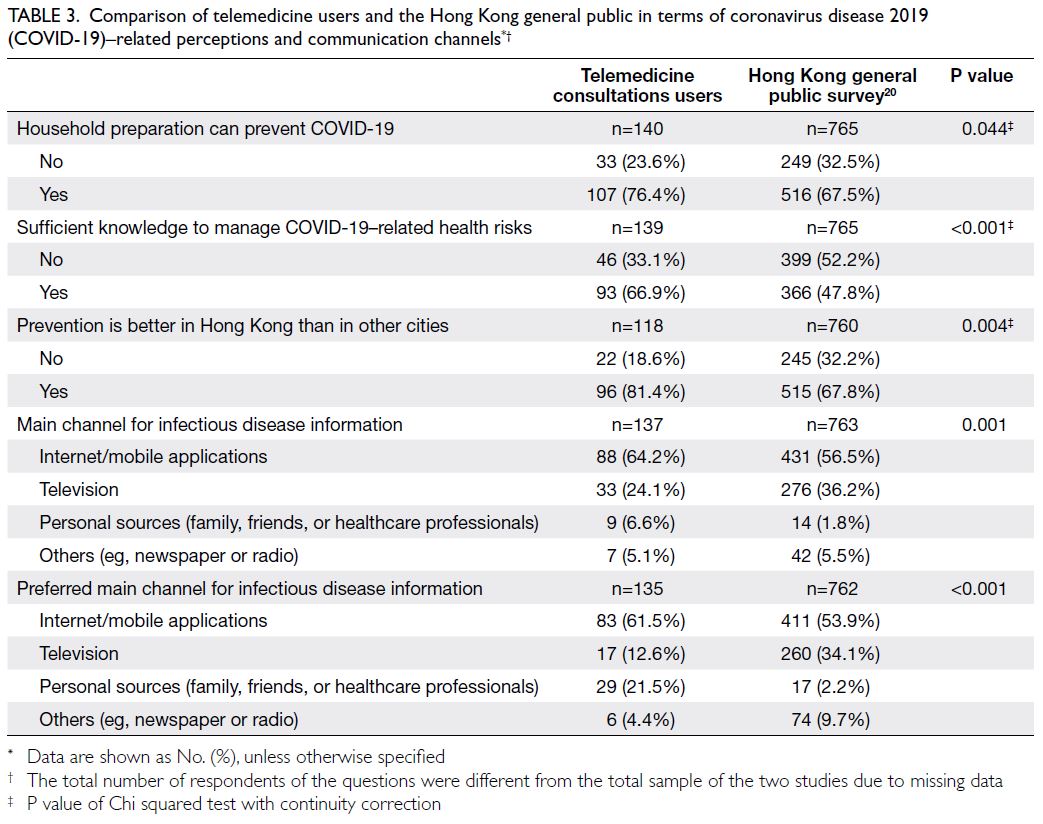

preparedness

Most telemedicine users (76.4%) believed that

household prevention could prevent COVID-19;

approximately 67% of them believed that they had

sufficient knowledge to manage COVID-19—related

health risks. These percentages were higher than

the percentages in the Hong Kong general public

telephone survey20 (Table 3). Additionally, >80% of telemedicine users believed that Hong Kong had

achieved better control of COVID-19, compared

with other major cities.

Table 3. Comparison of telemedicine users and the Hong Kong general public in terms of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)–related perceptions and communication channels

Regarding their main channel for infectious

disease information, approximately 64% of

participants were using the internet or mobile

applications, whereas 24% were using television;

these percentages differed from the Hong Kong

general public telephone survey, in which 56.5% of

respondents used the internet or mobile applications

and 36.2% used television20 (P<0.001). Overall,

telemedicine users preferred their main channel for

infectious disease information to be the internet or

mobile applications and personal sources (eg, family,

friends, or healthcare professionals).

Discussion

This study demonstrated high satisfaction with

telemedicine consultations among users and

revealed that users considered telemedicine to

be appropriate during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite the perception that telemedicine users

have sufficient knowledge to manage health risks

from COVID-19, when responses were compared

between telemedicine users and the Hong Kong

general public, we found that household preventative

measures were inadequate among telemedicine

users.

Acceptance of telemedicine

Most of our telemedicine users did not agree

that quality was identical between telemedicine

consultations and in-person consultations. This

perspective possibly resulted from the provision of

telemedicine consultations via telephone without

a video component; moreover, the users might not

have been familiar with the concept of telemedicine

consultation. Indeed, a 2014 nationwide survey in

the US revealed that only 15% of family physicians

reported using telemedicine in the previous

year; barriers included a lack of training, a lack of

reimbursement, the cost of equipment, and potential

liability issues.21 Furthermore, Schwamm22 has

described telemedicine as a disruptive technology

that may threaten traditional healthcare delivery.

Obstacles to the expansion of telemedicine in the US

include state-level statutes that require the clinician

to be located in the same state as the patient and to

have previously completed an in-person consultation

with that patient.23 Similar regulatory requirements exist in Hong Kong.24

Various studies in the US have detected

increasing uptake of telemedicine, particularly in

primary care.25 26 27 28 29 A study of telemedicine users in

a large commercially insured population in the US

from 2005 to 2017 showed that the mean age was

38.3 years; on average, users of primary care

telemedicine were younger than users of telemental

healthcare and more likely to reside in urban areas.25

A study regarding Teladoc, one of the largest telemedicine providers in the US, revealed that

Teladoc users were younger and less likely to have

used healthcare before the introduction of Teladoc;

they were also less likely to have a follow-up visit

in any setting, compared with patients who visited

a clinic for a similar condition.26 These findings

are consistent with our observations that most

telemedicine users were young; they also suggest

that the use of telemedicine services can provide

opportunities for healthcare access that are not

otherwise available.

Household preparations for coronavirus

disease 2019

Intriguingly, although more telemedicine users

agreed that household preparation could prevent

COVID-19, they were less likely to believe that their

household preventative measures were adequate,

compared with respondents in the Hong Kong

general public telephone survey.20 This disparity

may be attributed to differences in participant

characteristics: telemedicine users in this study were

younger (51% aged 18-24 years, vs 9% in the Hong

Kong general public20), were male (56% vs 47%20),

and were living in the New Territories (65% vs

51%20). Telemedicine users were also more likely to

use the internet (64% vs 57%20) as the main channel

for infectious disease information and to prefer

using the internet for such information (62% vs

54%20). These findings have important implications

for the use of telemedicine to fill gaps in health

promotion and disease prevention. Wu et al30 found

that secondary cases from household transmission

of COVID-19 were common in Zhuhai, China,

and one-third of these secondary cases were

asymptomatic. Sufficient household preparation

measures are needed to limit the spread of

COVID-19.31

Future use of telemedicine in Hong Kong

Telemedicine in Hong Kong had a ‘late start’ (in 1994);

in 1998, Hjelm32 predicted that the telemedicine would

be rapidly implemented in Hong Kong. However, in

the December 2019 version of the Ethical Guidelines

on Practice of Telemedicine by the Medical Council

of Hong Kong, it was noted that telemedicine in Hong

Kong has not fully developed.24 Despite the obvious

convenience benefit and reduced risk of COVID-19

transmission, the guidelines remind practitioners

that they remain fully responsible for legal and ethical

obligations during telemedicine consultations.24

Furthermore, the guidelines mention that standards

of care to protect patients are applicable during in-person

and telemedicine consultations; practitioners

should familiarise themselves with the World

Medical Association Statement on the Ethics of

Telemedicine.33

Training and patient assessment guidelines

for healthcare practitioners are urgently needed,

considering the unique circumstances surrounding

the use of telemedicine, such as technology (eg,

technical limitations of virtual consultations,

including assessments), patient education and

informed consent, cybersecurity, and other

concerns.6 These guidelines would ensure that the

same standards of telemedicine consultations can be

implemented, as described by the Medical Council

of Hong Kong.

Limitations

The present study focused on 141 telemedicine

users of a single private clinic providing deep

throat saliva polymerase chain reaction tests for

detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus 2; thus, the study participants may

not be representative of all telemedicine users in

Hong Kong. Responder bias may have affected the

results (the response rate was 75.4%), but it was not

possible to compare participants with individuals

who refused to participate. Furthermore, the recent

experience of a telemedicine consultation may

have biased participants’ responses in favour of

telemedicine.

Concerning the comparison of COVID-19

risk perception and preparedness measures,

methodological discrepancies between the online

survey of telemedicine users and the telephone

survey of the Hong Kong general public may have led

to differences in responses, particularly with respect

to including younger and more computer-literate

individuals in the online survey. Although the present

study was conducted from 6 April to 11 May 2020

(after a surge of COVID-19 cases in Hong Kong), the

Hong Kong general public telephone survey used

for comparison was conducted from 22 March to

1 April 2020 (during a surge in COVID-19 cases).20

The difference in data collection periods may have

contributed to different perceptions of COVID-19

preparedness. Various physical distancing measures

were implemented during the COVID-19 surge

(from late March to early April), which may also have

contributed to differences between the telephone

survey and online survey cohorts.

Finally, because of sample size limitations

and problems with representativeness, the findings

of the study may be restricted to understanding

views regarding telemedicine consultations among

participants in the present study. However, factors

such as young age, residence in private housing,

and residence in the New Territories may have

contributed to response bias; because no information

was collected concerning occupation, education

level, income, or ethnicity, we could not control for

bias related to these factors.

Conclusion

In this study, telemedicine users in Hong Kong

agreed that telemedicine consultations were

appropriate during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants agreed that telemedicine consultations

could perform the functions of health protection,

promotion, disease prevention, and diagnosis.

The use of telemedicine for screening and patient

education can be encouraged during the COVID-19

pandemic in Hong Kong.

Author contributions

Concept or design: KKC Hung, EYY Chan, JCY Wu.

Acquisition of data: KKC Hung, JCY Wu, CA Graham.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KKC Hung, EYY Chan, ESK Lo, Z Huang.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KKC Hung.

Acquisition of data: KKC Hung, JCY Wu, CA Graham.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KKC Hung, EYY Chan, ESK Lo, Z Huang.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KKC Hung.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding

agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Survey and Behavioural

Research Ethics Committee of The Chinese University of

Hong Kong (Ref No.: SBRE-19-730). Patients were treated

in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki

and provided written informed consent for all treatments and

procedures, as well as publication of their anonymised data.

References

1. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for

COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1679-81. Crossref

2. World Health Organization. Rapid assessment of service

delivery for NCDs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/rapid-assessment-of-service-delivery-for-ncds-during-the-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed 10 Aug 2020.

3. Peine A, Paffenholz P, Martin L, Dohmen S, Marx G,

Loosen SH. Telemedicine in Germany during the

COVID-19 pandemic: multi-professional national survey. J

Med Internet Res 2020;22:e19745. Crossref

4. Ford D, Harvey JB, McElligott J, et al. Leveraging health

system telehealth and informatics infrastructure to create

a continuum of services for COVID-19 screening, testing,

and treatment. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020;27:1871-7. Crossref

5. Gong K, Xu Z, Cai Z, Chen Y, Wang Z. Internet hospitals

help prevent and control the epidemic of COVID-19 in

China: multicenter user profiling study. J Med Internet Res

2020;22:e18908. Crossref

6. Kung K, Wong HF, Chen JY. An exploratory qualitative study on patients’ views of medical e-consultation in a public primary care setting. Hong Kong Pract 2016;38:120-7.

7. Greenhalgh T, Koh GC, Car J. COVID-19: a remote assessment in primary care. BMJ 2020;368:m1182. Crossref

8. Fagherazzi G, Goetzinger C, Rashid MA, Aguayo GA,

Huiart L. Digital health strategies to fight COVID-19

worldwide: challenges, recommendations, and a call for

papers. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e19284. Crossref

9. World Health Organization. A health telematics policy in

support of WHO’s Health-for-all strategy for global health

development: report of the WHO Group Consultation

on Health Telematics, 11-16 December, Geneva,

1997. 1998. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63857. Accessed 7 Sep 2023.

10. McLean S, Sheikh A, Cresswell K, et al. The impact of

telehealthcare on the quality and safety of care: a systematic

overview. PLoS One 2013;8:e71238. Crossref

11. Wootton R. Twenty years of telemedicine in chronic

disease management—an evidence synthesis. J Telemed

Telecare 2012;18:211-20. Crossref

12. Flodgren G, Rachas A, Farmer AJ, Inzitari M, Shepperd S.

Interactive telemedicine: effects on professional practice

and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2015;2015:CD002098. Crossref

13. Ekeland AG, Bowes A, Flottorp S. Effectiveness of

telemedicine: a systematic review of reviews. Int J Med

Inform 2010;79:736-71. Crossref

14. Eze ND, Mateus C, Cravo Oliveira Hashiguchi T.

Telemedicine in the OECD: an umbrella review of

clinical and cost-effectiveness, patient experience and

implementation. PLoS One 2020;15:e0237585. Crossref

15. Hung KK, Walline JH, Graham CA. COVID-19: emergency

medicine perspectives from Hong Kong. Eur J Emerg Med

2020;27:163-4. Crossref

16. Hung KK, Walline JH, Chan EY, et al. Health service

utilization in Hong Kong during the COVID-19

pandemic—a cross-sectional public survey. Int J Health

Policy Manag 2022;11:508-13. Crossref

17. Auener S, Kroon D, Wackers E, Dulmen SV, Jeurissen P.

COVID-19: a window of opportunity for positive healthcare

reforms. Int J Health Policy Manag 2020;9:419-22. Crossref

18. Sheng OR, Hu PJ, Chau PY, et al. A survey of physicians’

acceptance of telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare 1998;4

Suppl 1:100-2. Crossref

19. CUHK Medical Clinic. COVID-19 Testing Service

(Company/Groups). Available from: https://cuclinic.hk/programmes/covid-19-testing-service/covid-19-testing-testing-service-company-group. Accessed 30 Jul 2020.

20. Chan EY, Huang Z, Lo ES, Hung KK, Wong EL, Wong SY.

Sociodemographic predictors of health risk perception,

attitude and behavior practices associated with Health-Emergency Disaster Risk Management for biological

hazards: the case of COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong,

SAR China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:3869. Crossref

21. Moore MA, Coffman M, Jetty A, Petterson S, Bazemore A.

Only 15% of FPs report using telehealth; training and lack

of reimbursement are top barriers. Am Fam Physician

2016;93:101.

22. Schwamm LH. Telehealth: seven strategies to successfully

implement disruptive technology and transform health

care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:200-6. Crossref

23. Pearl R. Kaiser Permanente Northern California: current

experiences with internet, mobile, and video technologies.

Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:251-7. Crossref

24. The Medical Council of Hong Kong. Guidelines for all

registered medical practitioners. Available from: https://www.mchk.org.hk/files/newsletter-26th.pdf. Accessed 30 Jul 2020.

25. Barnett ML, Ray KN, Souza J, Mehrotra A. Trends in telemedicine use in a large commercially insured population, 2005-2017. JAMA 2018;320:2147-9. Crossref

26. Uscher-Pines L, Mehrotra A. Analysis of Teladoc use seems

to indicate expanded access to care for patients without

prior connection to a provider. Health Aff (Millwood)

2014;33:258-64. Crossref

27. Neufeld JD, Doarn CR. Telemedicine spending by

Medicare: a snapshot from 2012. Telemed J E Health

2015;21:686-93. Crossref

28. Mehrotra, A. The convenience revolution for treatment of

low-acuity conditions. JAMA 2013;310:35-6. Crossref

29. Courneya PT, Palattao KJ, Gallagher JM. HealthPartners’

online clinic for simple conditions delivers savings of

$88 per episode and high patient approval. Health Aff

(Millwood) 2013;32:385-92. Crossref

30. Wu J, Huang Y, Tu C, et al. Household transmission

of SARS-CoV-2, Zhuhai, China, 2020. Clin Infect Dis

2020;71:2099-108. Crossref

31. Chan EY, Gobat N, Kim JH, et al. Informal home care

providers: the forgotten health-care workers during the

COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020;395:1957-9. Crossref

32. Hjelm NM. Telemedicine: academic and professional

aspects. Hong Kong Med J 1998;4:289-92.

33. World Medical Association. WMA Statement on the

Ethics of Telemedicine. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-statement-on-the-ethics-of-telemedicine/. Accessed 15 Apr 2021.