Hong Kong Med J 2023 Jun;29(3):233–9 | Epub 25 May 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Five-year retrospective review of ultrasound-guided

manual vacuum aspiration for first-trimester miscarriage

Olivia SY Chau, MB, ChB, MRCOG1; Tracy SM Law, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; Karen Ng, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)1; TC Li, PhD (Sheffield), FRCOG2; Jacqueline PW Chung, FHKCOG, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)2

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Jacqueline PW Chung (jacquelinechung@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Manual vacuum aspiration is

increasingly accepted as an alternative to medical or

surgical evacuation of the uterus after first-trimester

miscarriage. This study aimed to assess the efficacy

of ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration

(USG-MVA) in the management of first-trimester

miscarriage.

Methods: This retrospective analysis included adult women with first-trimester miscarriage who

underwent USG-MVA in Hong Kong between July

2015 and February 2021. The primary outcome

was the efficacy of USG-MVA in terms of complete

evacuation of the uterus, without the need for

further medical or surgical intervention. Secondary

outcomes included tolerance of the entire procedure,

the success rate of karyotyping using chorionic villi,

and procedural safety (ie, any clinically significant

complications).

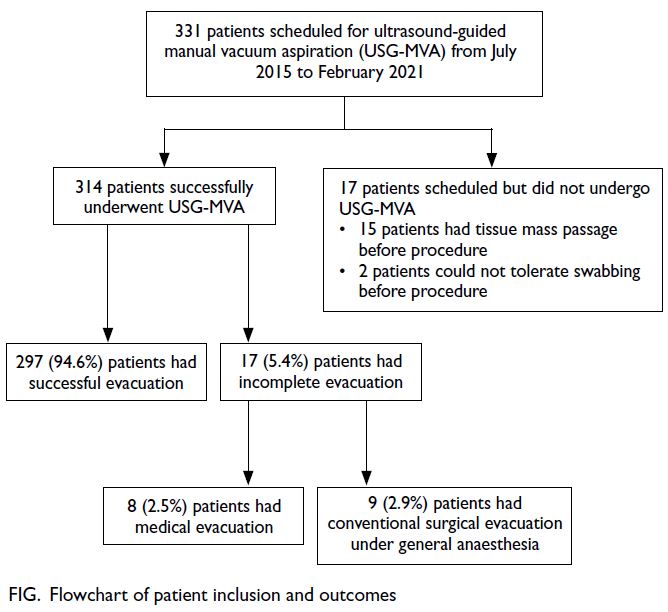

Results: In total, 331 patients were scheduled to

undergo USG-MVA for first-trimester miscarriage

or incomplete miscarriage. The procedure was

completed in 314 patients and well-tolerated in all

of those patients. The complete evacuation rate was

94.6% (297/314), which is similar to the rate (98.1%)

achieved by conventional surgical evacuation in a

previous randomised controlled trial in our unit. There were no major complications. Samples from

95.2% of patients were suitable for karyotyping,

which is considerably higher than the rate of suitable

samples (82.9%) obtained via conventional surgical

evacuation in our previous randomised controlled

trial.

Conclusion: Ultrasound-guided manual vacuum

aspiration is a safe and effective method to manage

first-trimester miscarriage. Although it currently

is not extensively used in Hong Kong, its broader

clinical application could avoid general anaesthesia

and shorten hospital stay.

New knowledge added by this study

- Ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration (USG-MVA) is a safe and effective method for the management of miscarriage, but its use is limited in Hong Kong.

- USG-MVA is similar in safety and efficacy to conventional surgical evacuation of the uterus (dilatation and curettage) under general anaesthesia for the management of miscarriage; it is well-tolerated by patients and causes minimal complications.

- USG-MVA is a good surgical option for women with miscarriage who wish to obtain products of conception for karyotyping.

- USG-MVA can be more widely implemented as an alternative to conventional dilatation and curettage/electrical vacuum aspiration of the uterus for the management of first-trimester miscarriage in Hong Kong.

- For women with recurrent miscarriage, USG-MVA should be considered because it has a higher rate of karyotyping success, compared with conventional suction evacuation of the uterus.

Introduction

Miscarriage occurs in 10% to 20% of pregnancies, and approximately one in four women will experience a

miscarriage in their lifetime.1 It is managed using one

of three approaches: expectant, medical, or surgical.

In 1972, manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) was introduced2 as an alternative method for the surgical

management of miscarriage. It is performed using

a handheld 60-mL syringe, which creates a suction

force to aspirate the contents of the uterus through

a cannula. This technique has various applications,

including the management of first-trimester miscarriage, incomplete or missed miscarriage,

endometrial biopsy, and first-trimester termination

of pregnancy; it can also be used after failed medical

evacuation of pregnancy. Because it only requires

simple oral analgesics or conscious sedation, this

procedure can be performed on an out-patient basis

in a treatment (or procedure) room; thus, it avoids

the use of a surgical theatre and the risks of general

anaesthesia, resulting in a shorter hospital stay.3

Conventional MVA is performed without

ultrasound guidance. However, because MVA is

performed on an out-patient basis without general

anaesthesia, ultrasound guidance may help to

minimise discomfort and procedure duration by

limiting the number of suction catheter passes and

achieving a higher rate of complete evacuation.

Studies by Elsedeek4 and Ali et al5 have shown that

ultrasound guidance allows clinicians to avoid

contact with the uterine fundus, leading to higher

rates of procedure completion, significantly lower

pain scores, and shorter procedure times. We

previously demonstrated that ultrasound-guided

manual vacuum aspiration (USG-MVA) is a feasible

and effective alternative surgical approach for first-trimester

miscarriage.6

Additionally, women with recurrent

miscarriage may prefer surgical evacuation (rather

than medical evacuation) because this approach

facilitates the acquisition of products of conception for cytogenetic analysis. The use of USG-MVA

causes less disruption of products of conception;

it also can aid in the identification of chorionic

villi for karyotyping. Therefore, USG-MVA may

be particularly useful for women with recurrent

miscarriage.

Ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration

is gaining acceptability, awareness, and recognition

in Hong Kong, although it is not commonly used

in clinical practice. To demonstrate the value

of the procedure, this study aimed to assess the

effectiveness of USG-MVA in the management of

first-trimester miscarriage.

Methods

Patient selection

This retrospective observational study included all women who underwent USG-MVA in Hong Kong

during the period from July 2015 to February 2021.

Eligible patients were identified by hospital records

in Prince of Wales Hospital and Union Hospital.

The indications for USG-MVA included missed or

incomplete miscarriage at <12 weeks of gestation,

as well as the desire for cytogenetic examination

of the products of conception to determine the

underlying cause of miscarriage. For naturally

conceived pregnancies, the date of the last menstrual

period was used to determine gestational age. For

artificially conceived pregnancies, gestational age

was determined according to the date of ovulation,

oocyte retrieval, or embryo transfer. All women

were counselled about the management options:

expectant, medical, conventional surgical (electrical

vacuum aspiration with or without dilatation and

curettage, under general anaesthesia), and USG-MVA.

Miscarriage was diagnosed by ultrasound

examination. A diagnosis of missed miscarriage

was made if a discrete embryo ≥7 mm without fetal

heart pulsation, or an intrauterine gestational sac

with a mean sac diameter of 25 mm excluding the

fetal pole, was detected on transvaginal ultrasound.

If only transabdominal ultrasound was performed,

the crown-rump length was recorded; a second scan

was performed 14 days later. A diagnosis of missed

miscarriage also was made if the mean sac diameter

was ≤25 mm without evidence of growth, or if there

was a sustained absence of fetal heart pulsation,

during a follow-up examination 7 to 14 days later.7 8

A diagnosis of incomplete miscarriage was

made if the ultrasound examination showed residual

products of conception after the initial passage,

defined as consistent intra-uterine thickness of

≥11 cm in the sagittal and transverse planes, and/or

if the patient experienced persistent symptoms such

as pain or bleeding.9

Patients were excluded if they had a known history of uterine anomalies, cervical stenosis, and/or multiple fibroids with uterine distortion. Patients

were also excluded if they had suspected infection,

an abnormal coagulation profile, haemodynamic

instability, and/or extreme anxiety that hindered

their ability to tolerate a pelvic examination.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the efficacy

of USG-MVA in terms of complete evacuation of

the uterus, without the need for further medical

or surgical intervention. We also compared the

complete evacuation rate with optimal outcomes in

our unit from a previous randomised controlled trial

(RCT) that involved other methods of miscarriage

management.10 Secondary outcomes included

whether patients could tolerate the entire procedure

without discontinuation prior to completion; the

success rate of karyotyping using chorionic villi

obtained from USG-MVA–collected samples,

compared with samples collected by conventional

surgical evacuation in our unit during the same

period; and procedural safety, defined as the

occurrence of any clinically significant complications

(eg, bleeding requiring blood transfusion, uterine

perforation, infection, and vasovagal shock).

Ultrasound-guided manual vacuum

aspiration procedure

Ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration was

performed on an out-patient basis in a treatment

room with a handheld syringe and flexible curette,

as well as an ultrasound machine. Each patient was

instructed to take misoprostol 400 μg orally 2 to

3 hours before the procedure for cervical priming;

they were also instructed to take naproxen 500 mg

1 hour before the procedure for pre-emptive pain

relief. Patients were instructed to take paracetamol

or codeine, rather than naproxen, if they were allergic

to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Upon

admission, patients were asked not to void because

a full bladder enables better visualisation of the

uterus on transabdominal ultrasound. Prophylactic

antibiotics were not routinely administered prior to

the procedure.

Ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration

was performed by an experienced clinician using a

60-mL handheld syringe with a self-locking plunge

(MedGyn Aspiration Kit; MedGyn Products,

Addison [IL], US) attached to a flexible curette (size

4-7 mm, according to clinician preference); a nurse

assisted with ultrasound guidance. During USG-MVA,

a speculum examination and swabbing were

performed with aseptic technique. A paracervical

block with 2% lidocaine was administered using a

Terumo Dental Needle (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). If

necessary, the clinician performing the procedure

could immobilise the cervix using a tenaculum. Local topical anaesthetic gel (xylocaine 2%) was applied

to the cervix and suction catheter. To guide curette

insertion into the uterine cavity, transabdominal

ultrasound was performed using a Voluson

E730 Expert USG system (GE Medical Systems,

Kretztechnik, Zipf, Austria). Suction was applied

with the handheld syringe to remove products of

conception, which were then immersed in normal

saline along with detached chorionic villi.

The USG-MVA procedure was completed

when the ultrasound examination showed a thin

endometrial lining, confirming that the uterine

cavity was empty. Products of conception were

sent to the laboratory for histological examination

and cytogenetic analysis, in accordance with each

patient’s preferences. All Rhesus-negative women

were administered anti-D prophylaxis.

Patients were discharged 2 to 3 hours after

the procedure if they were clinically healthy and

haemodynamically stable. A postoperative telephone

hotline was established; patients were advised to

contact the ward at any time if they encountered

excessive bleeding, abdominal pain, or fever. A

follow-up appointment was scheduled 2 to 3 weeks

after the procedure to ensure complete evacuation

had been achieved.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS (Windows

version 23.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

Data were expressed as counts and percentages.

Comparisons were conducted using the Chi squared

test for categorical variables and Student’s t test for

continuous variables. Two-tailed P values <0.05 were

considered statistically significant.

Results

In total, 331 patients were scheduled to undergo

USG-MVA during the study period. Seventeen of

these 331 patients did not undergo USG-MVA: 15

patients experienced passage of a tissue mass before

the procedure, and two patients could not tolerate

swabbing before the procedure. Thus, 314 patients

successfully underwent USG-MVA (Fig).

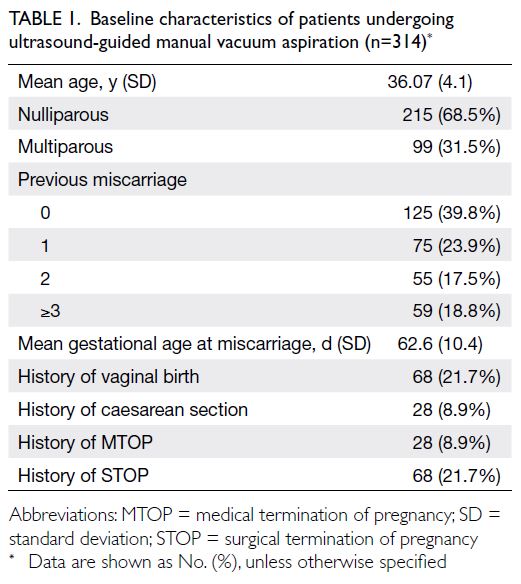

The baseline characteristics of the 314 included

patients are summarised in Table 1. All patients

received oral misoprostol for cervical priming;

all patients were able to tolerate and complete the

procedure. There were no major complications

such as uterine perforation or significant bleeding

(ie, requiring blood transfusion or uterotonics). All

patients were discharged within 3 hours after the

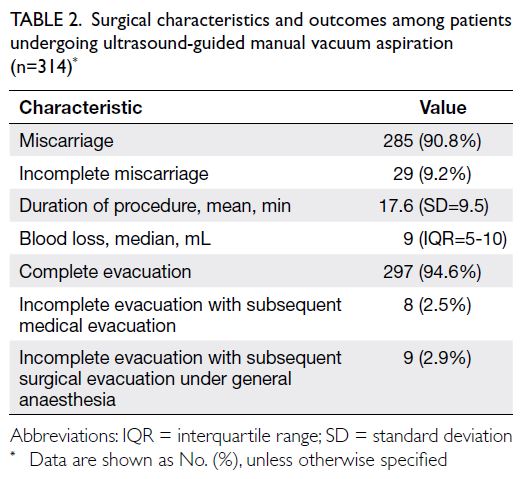

procedure. The complete evacuation rate was 94.6%

(297/314) [Table 2] and there were no unscheduled

readmissions.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients undergoing ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration (n=314)

Table 2. Surgical characteristics and outcomes among patients undergoing ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration (n=314)

With respect to the results of other miscarriage

management methods analysed in our previous

RCT,10 we found that USG-MVA had a significantly higher complete evacuation rate compared with

medical evacuation (94.6% vs 70%; P<0.001) or

expectant management (94.6% vs 79.3%; P<0.001).

Ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration also

had a complete evacuation rate that was comparable

with the rate achieved by conventional surgical evacuation (94.6% vs 98.1%10; P=0.024). Furthermore,

the rate of complete evacuation did not significantly

differ between women with missed miscarriage and

women with incomplete miscarriage (P=0.621).

Of the 17 patients (5.4%) who had incomplete

evacuation during USG-MVA, eight (2.5%)

subsequently underwent medical evacuation,

whereas nine (2.9%) selected conventional surgical

evacuation under general anaesthesia (Table 2).

In terms of histological examination, 66.2% of

patients (208/314) requested karyotyping. Among

samples from those patients, 95.2% (198/208) were

suitable for karyotyping; the culture failure rate

was 4.8% (10/208). During the same period, 82.9%

(295/356) of samples obtained via conventional

surgical evacuation10 were suitable for karyotyping,

which is significantly lower than the 95.2% of samples

obtained via USG-MVA (P<0.001).

Among the samples that were suitable for

karyotyping, 65.7% (130/198) had an abnormal

karyotype and 34.3% (68/198) had a normal

karyotype. Of the 10 samples that were unsuitable

for karyotyping, eight contained no chorionic villi,

whereas two had a limited number of villi; these

characteristics contributed to culture failure.

Discussion

Since our unit introduced MVA as an alternative to conventional surgical evacuation of the uterus for

first-trimester miscarriage, it has generally been

well-received by eligible patients.11 Manual vacuum

aspiration constitutes a safe and effective uterine

evacuation procedure; it is widely used in other

countries, including the United States and United

Kingdom.11 12 13 14 Thus far, MVA is not commonly used

in Hong Kong, possibly because there is a lack

of familiarity with the procedure. This study was

conducted to explore the utilisation and outcomes of

USG-MVA, particularly with respect to the complete evacuation rate, safety, tolerability, and successful

acquisition of chorionic villi for karyotyping.

In this study, the complete evacuation rate of

USG-MVA was 94.6%, which is within the range

of 89% to 98% reported in previous studies.12 15 The

complication rate was low, tolerability was good,

and the proportion of samples that were suitable for

karyotyping was high.

The complete evacuation rate achieved using

conventional dilatation and curettage reportedly

ranges from 88% to 98%,16 17 which is consistent

with previous data from our unit (98.1%).10 These

rates are comparable with the rate achieved using

USG-MVA in the present study. Moreover, complete

evacuation rates achieved via medical management

were 84% in an RCT by Zhang et al18 and 70% in our

unit10; complete evacuation rates after expectant

management reportedly ranged from 16% to 76%,19 20

similar to the rate of 79.3% observed in our unit.10

Overall, the complete evacuation rate achieved via

medical or expectant management is substantially

lower than the rate achieved using USG-MVA.

Clinical implications

The rate of complications associated with

conventional dilatation and curettage is reportedly

similar21 to the rate of complications associated

with MVA; neither approach has been linked to

major complications. These low complication rates

may be related to the use of ultrasound guidance,

which lowers the risk of uterine perforation or false

tract creation. There is evidence that ultrasound

guidance for dilatation and curettage reduces the

complication rate.22 23 In an RCT that investigated

the use of ultrasound guidance during surgical

termination of pregnancy, Acharya et al24 found

significant reductions in infection rates, retained

products of conception requiring repeat evacuation,

and volume and duration of bleeding in patients who

underwent the procedure with ultrasound guidance.

Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that USG-MVA

also has a lower complication rate, compared with

conventional MVA lacking ultrasound guidance.

However, ultrasound guidance requires additional

equipment and staff with appropriate ultrasound

probe training. Further research is needed to clearly

determine whether the use of ultrasound during

MVA provides a clinical benefit.

Because USG-MVA is an out-patient procedure

performed with local anaesthesia in a procedure

room, it does not require a surgical theatre or

surgical staff. These modified requirements could

reduce costs and allow the surgical theatre to be used

for other procedures. Patients also would also not

be required to fast for a prolonged period prior to

general anaesthesia, which would reduce discomfort

related to the miscarriage experience. Since a general

anaesthesia is not required, it would facilitate a shorter hospital stay, allowing patients to return

more rapidly to the comfort of their home after the

procedure. Other benefits include the potential for

reduced clinical costs and the availability of beds for

other patients who require hospitalisation.

This study also demonstrated that a large

proportion of samples obtained by USG-MVA

are suitable for karyotyping, which is particularly

important for women with recurrent miscarriage.

The culture failure rates with products of conception

obtained via conventional suction evacuation

reportedly range from 10% to 40%25; these rates

are higher than the culture failure rate using

samples obtained by USG-MVA in the present

study. Karyotyping requires relatively intact and

fresh samples, which are often difficult to obtain

by medical evacuation. The products of conception

may be passed hours before a sample is sent to the

laboratory; they may also be accidentally discarded

by the patient.26 During conventional suction

evacuation, the products of conception may be

extensively damaged by the curette, leading to a

higher rate of culture failure.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first large study in Hong Kong to assess USG-MVA over an extended

period. It provides a clear picture of the utilisation

of USG-MVA in Hong Kong, with important

information regarding the complete evacuation rate,

safety, and tolerability of the procedure.

A notable limitation in this study was its

retrospective design. Although MVA is generally

well-tolerated by patients, as demonstrated in

previous studies,3 11 12 15 it causes greater discomfort

than conventional dilatation and curettage under

general anaesthesia.11 In the present study, tolerability

was determined by review of patient medical

records; it was solely based on whether a patient had

been able to tolerate the entire procedure, and no

measurement of pain was conducted. The use of a

visual analogue scale score during the procedure may

provide a better indication of the actual tolerability

of the procedure. A previous trial of USG-MVA,

conducted by our unit to investigate the efficacy

of hyoscine butylbromide in reducing uterine

contraction pain during the procedure, showed

a slight reduction in pain score compared with

placebo.6 Additional methods could be investigated

to improve pain control during USG-MVA.

Furthermore, some patients may have

experienced pain because misoprostol was

administered for cervical priming prior to the

procedure; this was intended to facilitate insertion

of the suction catheter. The MedGyn Aspiration

Kit provides suction catheters in sizes 4 to 7; if

necessary, dilatation could thus be performed under

ultrasound guidance using the suction catheters, thereby eliminating the need for misoprostol before

the procedure and reducing the amount of pain

involved in USG-MVA.

The clinicians who performed USG-MVA in

this study ranged from supervised junior trainees to

attending physicians with many years of experience.

Although the procedures were performed by

experienced clinicians who had completed at least

30 MVA procedures before independent practice,

or by trainees who were directly supervised by

an experienced clinician, differences in clinician

experience have the potential to influence the rate

of complete evacuation and the amount of pain

involved. A standardised approach involving a few

dedicated clinicians may reduce this variation.

In this study, data were available concerning

the complete evacuation rate achieved by dilatation

and curettage in our unit and also from the Union

Hospital; however, no data were available from

Union Hospital, where USG-MVA is also performed.

Additionally, the present study was not designed to

allow a comprehensive comparison of miscarriage

management methods. In the future, a well-designed

RCT should be conducted to compare outcomes

among USG-MVA, surgical evacuation, and medical

evacuation.

Importantly, no long-term follow-up was

performed in this study; thus, we could not examine

the long-term effects of USG-MVA.

Future research

Ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration is

regarded as a safe, simple, efficient, and cost-effective

procedure. It allows patients to maintain greater

autonomy, avoids the risks of general anaesthesia,

and has a higher success rate in terms of collecting the

products of conception for karyotyping. However,

USG-MVA remains an invasive procedure, and some

patients may not be able to endure the physical or

(possible) emotional pain involved.27 The addition of

ultrasound guidance to MVA may reduce the number

of suctions required for complete evacuation and

help clinicians avoid contacting the uterine fundus,

thereby minimising the duration and severity of pain

during the procedure. Further research is needed

regarding approaches to minimise the physical and

emotional pain that patients may experience during

the procedure, such as the use of other pain-relieving

agents to minimise discomfort during the procedure.

Research is also needed to identify other potential

advantages of USG-MVA with respect to other

methods of miscarriage management. Moreover,

prospective studies comparing pain scores with

visual analogue scale scores and patient satisfaction

are needed to determine whether the addition of

ultrasound guidance to MVA has a meaningful effect

on pain outcomes.

Because USG-MVA is an out-patient

procedure that does not require a surgical theatre,

an anaesthetist, and an overnight stay, it may be

significantly less expensive than conventional

surgical evacuation of the uterus. The cost of

a USG-MVA procedure includes the MedGyn

Aspiration Kit, which costs approximately US$18. A

cost-effectiveness study is needed to fully explore the

potential for reduced clinical costs.

Future research should also focus on the

potential effects of USG-MVA on fertility. Asherman’s

syndrome, caused by trauma to the basal layer of the

uterus, is most commonly associated with dilatation

and curettage28; it is detected in approximately

20% of patients after dilatation and curettage.29

We hypothesise that the use of USG-MVA without

curettage may reduce endometrial trauma and the

number of intrauterine adhesions, thereby lowering

effects on future fertility. Currently, our unit is

investigating this hypothesis via second-look out-patient

hysteroscopy.

Conclusion

Ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration

is a safe and effective alternative to medical and

conventional suction evacuation, with minimal

complications (eg, uterine perforation, bleeding, and

retained products of conception). Patients can avoid

the risks of general anaesthesia and have a shorter

hospital stay. Ultrasound-guided manual vacuum

aspiration may be appropriate for patients with first-trimester

miscarriage, particularly women who have

experienced recurrent miscarriage and express a

desire for karyotyping.

Author contributions

Concept or design: OSY Chau, TC Li, JPW Chung.

Acquisition of data: OSY Chau, TC Li, JPW Chung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: OSY Chau, JPW Chung.

Drafting of the manuscript: OSY Chau, JPW Chung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: OSY Chau, TC Li, JPW Chung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: OSY Chau, JPW Chung.

Drafting of the manuscript: OSY Chau, JPW Chung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, JPW Chung was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no

conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank all women who participated in this trial. We also express gratitude to Ms Margaret Hiu-tan Lee, Dr Ying Li,

Ms Cheryl Lee, and Ms Yi-tso Kwan from the Department of

Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong

Kong for assistance in this study.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The human study protocol was approved by the

Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong—New Territories East

Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Ref No.: CREC-2021-206) and the Union Hospital Ethics Committee (Ref No.:

EC025), Hong Kong. All adult participants provided written

informed consent for inclusion in this study. The STROBE

(Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in

Epidemiology) guidelines were followed when reporting this

study.

References

1. Webster K, Eadon H, Fishburn S, Kumar G; Guideline Committee. Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis

and initial management: summary of updated NICE

guidance. BMJ 2019;367:l6283. Crossref

2. Karman H, Potts M. Very early abortion using syringe as vacuum source. Lancet 1972;1:1051-2. Crossref

3. Sharma M. Manual vacuum aspiration: an outpatient alternative for surgical management of miscarriage. Obstet

Gynaecol 2015;17:157-61. Crossref

4. Elsedeek MS. Comparison between the traditional non-guided and a novel ultrasound-guided technique for office

fitting of intrauterine contraceptive devices. Int J Gynecol

Obstet 2016;133:338-41. Crossref

5. Ali MK, Ramadan AK, Abu-Elhassan AM, Sobh AM. Ultrasound-guided versus uterine sound-sparing approach

during copper intrauterine device insertion: a randomised

clinical trial. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care

2022;27:3-8. Crossref

6. Chung JP, Law TS, Mak JS, Liu RC, Sahota DS, Li TC. Hyoscine butylbromide in pain reduction associated

with ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration: a

randomized placebo-controlled trial. Reprod Biomed

Online 2022;44:295-303. Crossref

7. Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, et al. Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1443-51. Crossref

8. Wie JH, Choe S, Kim SJ, Shin JC, Kwon JY, Park IY. Sonographic parameters for prediction of miscarriage: role

of 3-dimensional volume measurement. J Ultrasound Med

2015;34:1777-84. Crossref

9. Bar-Hava I, Aschkenazi S, Orvieto R, et al. Spectrum of normal intrauterine cavity sonographic findings after first-trimester abortion. J Ultrasound Med 2001;20:1277-81. Crossref

10. Kong GW, Lok IH, Yiu AK, Hui AS, Lai BP, Chung TK. Clinical and psychological impact after surgical, medical

or expectant management of first-trimester miscarriage—a

randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol

2013;53:170-7. Crossref

11. Chung JP, Chung CH, Mak JS, Li TC, Kong GW. Efficacy, feasibility and patient acceptability of ultrasound-guided manual vacuum aspiration for treating early pregnancy

loss. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2019;59:71-6. Crossref

12. Milingos DS, Mathur M, Smith NC, Ashok PW. Manual vacuum aspiration: a safe alternative for the surgical management of early pregnancy loss. BJOG 2009;116:1268-71.Crossref

13. Macisaac L, Darney P. Early surgical abortion: an alternative to and backup for medical abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183 (2 Suppl):S76-83. Crossref

14. Morrison J. The care of women requesting induced abortion. Guideline No. 7. J Obstet Gynaecol 2003;23:521-4. Crossref

15. Tasnim N, Mahmud G, Fatima S, Sultana M. Manual

vacuum aspiration: a safe and cost-effective substitute of

electric vacuum aspiration for the surgical management of

early pregnancy loss. J Pak Med Assoc 2011;61:149-53.

16. Sajan R, Pulikkathodi M, Vahab A, Kunjitty VM, Imrana

HS. Expectant versus surgical management of early

pregnancy miscarriages—a prospective study. J Clin Diagn

Res 2015;9:QC06-9. Crossref

17. Wen J, Cai QY, Deng F, Li YP. Manual versus electric

vacuum aspiration for first-trimester abortion: a systematic

review. BJOG 2008;115:5-13. Crossref

18. Zhang J, Gilles JM, Barnhart K, et al. A comparison of

medical management with misoprostol and surgical

management for early pregnancy failure. N Engl J Med

2005;353:761-9. Crossref

19. Shelley JM, Healy D, Grover S. A randomised trial of surgical, medical and expectant management of first

trimester spontaneous miscarriage. Aust N Z J Obstet

Gynaecol 2005;45:122-7. Crossref

20. Jurkovic D, Ross JA, Nicolaides KH. Expectant management of missed miscarriage. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;105:670-1.Crossref

21. Goldberg AB, Dean G, Kang MS, Youssof S, Darney PD.

Manual versus electric vacuum aspiration for early first-trimester

abortion: a controlled study of complication

rates. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:101-7. Crossref

22. Hornstein MD, Osathanondh R, Birnholz JC, et al. Ultrasound guidance for selected dilatation and evacuation procedures. J Reprod Med 1986;31:947-50.

23. Chaikof M, Lazer T, Gat I, et al. Lower complication rates with office-based D&C under ultrasound guidance for missed abortion. Minerva Ginecol 2017;69:23-8. Crossref

24. Acharya G, Morgan H, Paramanantham L, Fernando R. A randomized controlled trial comparing surgical

termination of pregnancy with and without continuous

ultrasound guidance. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol

2004;114:69-74. Crossref

25. Shah MS, Cinnioglu C, Maisenbacher M, Comstock I,

Kort J, Lathi RB. Comparison of cytogenetics and molecular

karyotyping for chromosome testing of miscarriage

specimens. Fertil Steril 2017;107:1028-33. Crossref

26. Soler A, Morales C, Mademont-Soler I, et al. Overview of

chromosome abnormalities in first trimester miscarriages:

a series of 1,011 consecutive chorionic villi sample

karyotypes. Cytogenet Genome Res 2017;152:81-9. Crossref

27. Yu FN, Leung KY. Diagnosis and prediction of miscarriage:

can we do better? Hong Kong Med J 2020;26:90-2. Crossref

28. Asherman JG. Traumatic intra-uterine adhesions. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp 1950;57:892-6. Crossref

29. Hooker AB, Lemmers M, Thurkow AL, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of intrauterine adhesions after

miscarriage: prevalence, risk factors and long-term

reproductive outcome. Hum Reprod Update 2014;20:262-78. Crossref