© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Public awareness of preventive measures against

COVID-19: an infodemiology study

Alex Mok, MB, ChB1; Oliver OY Mui, MB, ChB1; KP Tang, MB, ChB1; WY Lee, MB, ChB1; CF Ng, MD, FRCSEd (Urol)1; Sunny H Wong, MB, ChB, DPhil (Oxon)2; Martin CS Wong, MD, MB, ChB3,4; Jeremy YC Teoh, MB, BS, FRCSEd (Urol)1,5

1 SH Ho Urology Centre, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

4 Centre for Health Education and Health Promotion, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

5 Office of Global Engagement, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Prof Jeremy YC Teoh (jeremyteoh@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) pandemic has led to an increase in

global awareness of relevant public health preventive

measures. This awareness can be explored using

online search trends from major search engines, such

as Google Trends. We investigated the relationship

between public awareness of preventative measures

and progression of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: Search data for five queries (‘mask’, ‘hand

washing’, ‘social distancing’, ‘hand sanitizer’, and

‘disinfectant’) were extracted from Google Trends

in the form of relative search volume (RSV). Global

incidence data for COVID-19 were obtained from 1

January to 30 June 2020. These data were analysed

and illustrated using a global temporal RSV trend

diagram, a geographical RSV distribution chart,

scatter plots comparing geographical RSV with

average number of daily cases, and heat maps

comparing temporal trends of RSV with average

number of daily cases.

Results: Global temporal trends revealed multiple increases in RSV, associated with specific COVID-19–related news events. The geographical

distribution showed top regions of interest for

various preventive measures. For the queries ‘mask’,

‘hand washing’, ‘hand sanitizer’, and ‘disinfectant’,

heat maps demonstrated patterns of early RSV peaks

in regions with lower average number of daily cases,

when the temporal element was incorporated into the analysis.

Conclusion: Early public awareness of multiple

preventive measures was observed in regions with

lower average number of daily cases. Our findings

indicate optimal public health communication

regarding masks, hand washing, hand sanitiser, and

disinfectant in the general population during early

stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Early public

awareness may facilitate future disease control

efforts by public health authorities.

New knowledge added by this study

- This study focused on the importance of early public awareness in controlling coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19); this effect was not extensively investigated in previous studies.

- Early awareness trends among regions with lower average number of daily cases were illustrated using heat maps for the queries ‘mask’, ‘hand washing’, ‘hand sanitizer’, and ‘disinfectant’.

- In contrast to prior infodemiology studies, this study used a global online approach and focused on specific preventive measures recommended by the World Health Organization.

- This study revealed correlations between regions with low average number of daily cases of COVID-19 and early public awareness of multiple preventive measures (ie, ‘mask’, ‘hand washing’, ‘hand sanitizer’, and ‘disinfectant’). Health policies should seek to promote these preventive measures among the general public, which could help to slow the spread of disease. Furthermore, early public awareness may help public health authorities to control future global public health crises.

- This study also investigated the effects of authorities, public figures, and social media on public health awareness. Future healthcare policies should consider these factors to effectively promote correct public health information among the general public.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) began in

December 2019 in Wuhan, China, and became

a public health crisis affecting millions of people

worldwide.1 On 11 March 2020, the World Health

Organization (WHO) declared that COVID-19

constituted a pandemic2; by 1 September 2020, the

total number of confirmed COVID-19 cases had

exceeded 26 million, with over 800 000 deaths.3

Accordingly, the WHO issued

recommendations to the general public with the goal

of reducing community transmission of COVID-19.

These recommended preventive measures included

the use of masks in specific situations as well as hand

washing, social distancing, and various other disease

prevention strategies.4 In the early and middle

of 2020, there was no specific treatment to cure

the aggressively spreading virus; thus, preventive

measures and public awareness of such information

had important roles in the formulation of public

health policies.

Because of technological advancements in

recent decades, the internet has become a convenient

and effective channel for providing readily accessible

and up-to-date public health information to members

of the general public. In the era of big internet

data, infodemiology—an emerging area of science

that explores the distribution and determinants

of information in electronic media—has been

implemented in multiple areas of modern medicine.5

The analysis of large amounts of internet data enables

researchers to identify trends in online search

behaviour; this information can be used to analyse

relationships among public health communication,

public awareness, and the progression of disease

outbreaks. Indeed, search trends from major search

engines (eg, Google) have been extensively used in

infodemiology and infoveillance studies focused on

outbreak patterns and public awareness,6 particularly

with respect to the Ebola,7 8 9 H1N1 influenza,10 11 and

Zika12 13 14 viruses.

In the context of COVID-19, various

infodemiology investigations have been conducted,

ranging from the impacts of COVID-19 on domestic

abuse15 and psychological distress,16 17 to its

impacts on social media discourse.18 In particular,

previous infodemiology studies used Google data to

examine public awareness of COVID-19 in various

countries.19 20 21 22 23 Analyses of other popular websites,

such as Wikipedia, revealed an increase in public

awareness of health-related topics during the

COVID-19 pandemic.24 However, previous regional

studies did not utilise extensive datasets with respect

to time period, number of countries, and all five

WHO-recommended preventive measures that

were selected in this study. Additionally, previous

studies did not explore how early public awareness

of preventive measures is related to lower average number of daily cases in specific countries.

This study was conducted to explore

relationships between early public awareness of

preventative measures and the progression of the

COVID-19 pandemic through the interpretation of

Google searches regarding multiple public health

preventive measures. The results are expected

to provide guidance for future public health

communication and policy decisions.

Methods

Overview of Google Trends and global

incidence data

To explore the relationship between public

awareness of specific preventive measures against

COVID-19 and the progression of COVID-19

pandemic, search data were extracted from Google

Trends (GT) and compared with global incidence

data for COVID-19. The global incidence data,

measured in number of cases, were retrieved from

the COVID-19 Data Repository by the Centre for

Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins

University of the US.3 Next, the average number of

daily cases in each country/region was calculated

based on the total number of cases in that country/region between the date of the first locally reported

case and 30 June 2020.3 Google Trends provides

quantitative information regarding actual search requests on Google for specific terms, in the form

of relative search volume (RSV). The RSV is the

volume of a search query for a specified location

and period of time, normalised both geographically

and temporally. The data are expressed using a range

from 0 to 100, depending on the ratio of searches for

that topic to all searches for all topics on Google.25 26

When conducting an infodemiology study using GT

data, accurate keyword, region, and period selections

must be made according to the study aims.25 26

Keyword, region, and period selections

Based on WHO recommendations27 and top-ranked

Google search queries related to COVID-19, we

selected ‘mask’, ‘hand washing’, ‘social distancing’,

‘hand sanitizer’, and ‘disinfectant’ as keywords that

represented public interest in preventive measures

against COVID-19. For each keyword, data were

retrieved from GT according to ‘search topic’ (where

available), which allowed simultaneous analysis of

five queries.28 In contrast to the ‘search term’ option,

‘search topic’ is a ‘group of terms that share the

same concept in any language’.26 By analysing GT

data in the form of search topics, we were able to

accommodate differences in language, translation,

terminology, and spelling of the same concept.

In terms of region selection, GT normalises

data differently according to geographical level.26 In

this study, we retrieved both global- and country-level

data depending on the analysis; global-level

data were used to analyse general trends in public

interest and geographical distribution, whereas

country-level data were used to analyse correlations.

Global incidence data for 190 countries/regions

worldwide are available from the aforementioned

Johns Hopkins University database. To clarify the

terminology used in this study, ‘geographical RSV’

data were normalised according to search volume

in individual regions over a fixed period of time

through analyses of ‘interest by region’ in worldwide

searches. In contrast, ‘temporal RSV’ data were

normalised according to daily search volume over

time, either globally or regionally, through analyses

of ‘interest over time’ in either worldwide or regional

searches.

Furthermore, global incidence data and GT-based

RSV data were collected for the period from 1

January to 30 June 2020. The period selected for GT

data completely matched the study period, consistent

with published guidance.26 As mentioned above, a

primary goal of this study was the examination of

global public awareness during early stages of the

COVID-19 pandemic. To examine awareness before

local outbreaks, a universal start date was selected,

rather than the date of the first reported case in

each country/region (used in the aforementioned

calculation of average number of daily cases).

According to the timeline of WHO’s response to COVID-19,29 the first event involving all three levels

of the WHO (headquarters, regional, country)

occurred on 1 January 2020; accordingly, this date

was selected as the start date for this study. Because

GT data are proportional to all searches for all topics

over time, it is important to note that the GT data

used in this study were last retrieved on 7 November

2020.26

Data analysis

To illustrate the global temporal RSV trends for

each query throughout the study period, global

RSV data for each search topic were extracted and

plotted on line graphs, where RSV was proportional

to worldwide temporal search volume. Moreover, for

each individual query, the geographical distribution

of RSV was analysed and summarised in a table

listing the top 20 regions of interest.

We analysed correlations between geographical

RSV trends for each query and average number of

daily cases in each country/region, whereby RSV

was normalised according to overall regional search

volume throughout the study period. Correlations

were presented using scatter plots, and Pearson

correlation coefficients were calculated. To avoid

pre-analytical errors, we used the default GT setting

of excluding regions with low search volume.

The temporal element of RSV trends in

each country/region is necessary to illustrate

the importance of early awareness. Therefore,

temporal RSV trends in each region were extracted

separately for each query; the RSV for each region

was normalised according to the search volume

of individual days in that region. Temporal RSV

trends were then plotted against the lists of regions

(excluding regions with low search volume) on five

individual heat maps. In each heat map, the y-axis

depicts the region list sorted from highest to lowest

average number of daily cases, whereas the x-axis

represents the timeline from 1 January to 30 June

2020. A three-colour scale of green, yellow, and red

was used to represent low, medium, and high RSV,

respectively.

Results

Global temporal trends

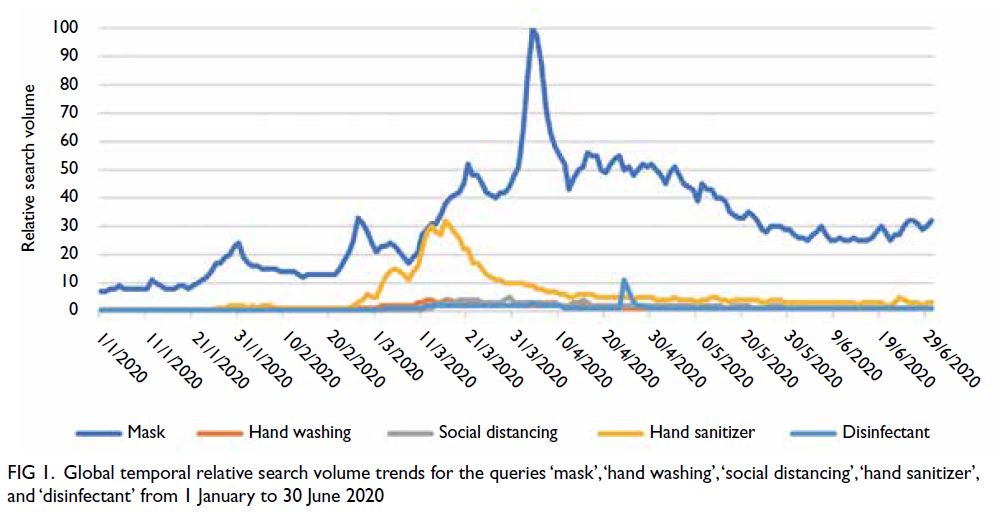

Figure 1 shows the global temporal RSV trends of

the five queries in this study, namely, ‘mask’, ‘hand

washing’, ‘social distancing’, ‘hand sanitizer’, and

‘disinfectant’. ‘Mask’ was the query that consistently

demonstrated the greatest global RSV throughout

the study period; at its peak, it exceeded the peak of

the second highest query, ‘hand sanitizer’, by more

than threefold.

Figure 1. Global temporal relative search volume trends for the queries ‘mask’, ‘hand washing’, ‘social distancing’, ‘hand sanitizer’, and ‘disinfectant’ from 1 January to 30 June 2020

With respect to the query ‘mask’, the greatest

peak occurred on 4 April 2020, and three other

peaks were identified (31 January 2020, 26 February 2020, and 21 March 2020). In particular, the peak on

4 April 2020 (RSV=100) corresponded to the WHO’s

announcement of 1 000 000 cases worldwide.30 The

peak on 31 January 2020 (RSV=24) corresponded to

the WHO Director-General’s Statement regarding

the International Health Regulations Emergency

Committee on 30 January 2020, in which COVID-19

was declared a ‘Public Health Emergency of

International Concern’.31 Similarly, the peak on

26 February 2020 (RSV=33) corresponded to the

WHO release of guidelines entitled ‘Rational use

of personal protective equipment for coronavirus

disease’,32 which detailed preventative measures

such as hand hygiene (soap/alcohol sanitiser), use of

masks, and social distancing.

The RSV peak for the query ‘hand sanitizer’

on 13 March 2020 (RSV=30) corresponded to the

WHO’s press release declaring that COVID-19 was

a pandemic, during a media briefing on 11 March

2020.2 This peak was also accompanied by an article

in The New York Times describing a shortage of hand

sanitiser.33

Another major peak, visible without extensive

data analysis, was recorded for the query ‘disinfectant’

on 24 April 2020. Unlike the other peaks, which

gradually increased, the query ‘disinfectant’

increased from an RSV of 1/100 on 23 April 2020 to

11/100 on the following day; this 11-fold increase is

visible in Figure 1.

Geographical distribution

With respect to country-level interest in the query ‘mask’ (online supplementary Table), the highest

RSV was observed in Hong Kong (100), followed by

Singapore (87) and France (75). The highest country-level countrylevel

RSV values for ‘hand washing’ were observed

in Indonesia (100), Vietnam (100), and Hong Kong

(88), while that for ‘social distancing’ were recorded

in Canada (100), Indonesia (95), and Singapore (92).

For ‘hand sanitizer’, the highest country-level RSV

values were recorded in Hong Kong (100), Singapore

(96), and Denmark (91). For ‘disinfectant’, the highest

country-level RSV values were observed in the US

(100), the Philippines (88), and Singapore (79).

The full list of geographical distributions showing

all countries/regions is included in the online supplementary Table.

Correlations between geographical relative

search volume trends and average number of daily cases

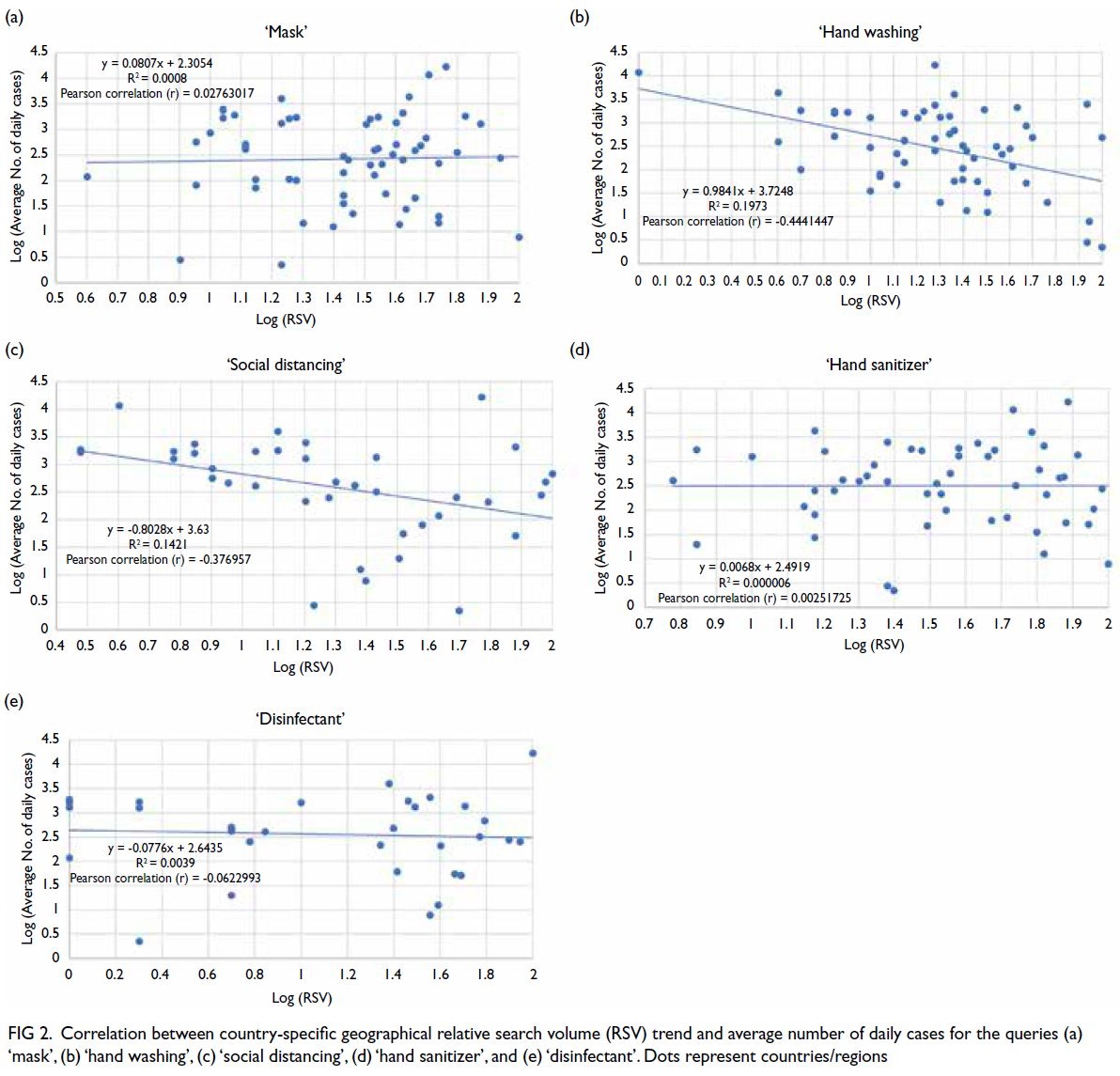

Figure 2 shows the correlation between the average

number of daily cases for each country/region and

the LogRSV of each respective search query from

1 January to 30 June 2020. ‘Hand washing’ and

‘social distancing’ were the only queries with mild

correlations, with Pearson correlations (r values) of

-0.44 (‘hand washing’) and -0.38 (‘social distancing’).

No strong correlations were observed for the other

three terms ‘mask’ (r=0.03), ‘hand sanitizer’ (r=0.00),

and ‘disinfectant’ (r=-0.06).

Figure 2. Correlation between country-specific geographical relative search volume (RSV) trend and average number of daily cases for the queries (a) ‘mask’, (b) ‘hand washing’, (c) ‘social distancing’, (d) ‘hand sanitizer’, and (e) ‘disinfectant’. Dots represent countries/regions

Correlations between temporal relative

search volume trends in each region and

average number of daily cases

The online supplementary Figure shows heat maps

for the five search queries. In online supplementary Figure a, a divergence pattern was observed for the

search query ‘mask’, which tended to display an

earlier RSV peak in countries/regions with lower average number of daily cases and a later RSV peak

in countries/regions with higher average number

of daily cases. Among the countries/regions with

an early RSV peak and low average number of daily

cases, Hong Kong had an early RSV peak (100) on

29 January 2020 and an average number of daily

case count of 7.75. Other notable examples include

Taiwan (early RSV peak on 3 February 2020 and

average number of daily case count of 2.79) and

Vietnam (early RSV peak on 31 January 2020 and

average number of daily case count of 2.23). In

contrast, countries/regions with a late RSV peak and high average number of daily cases included the US

(late RSV peak on 4 April 2020 and average number

of daily case count of 16789.11), Brazil (late RSV

peak on 3 April 2020 and average number of daily

case count of 11590.02), and Russia (late RSV peak

on 30 March 2020 and average number of daily case

count of 4327.68).

Similarly, online supplementary Figures b, d, and e show heat maps for the search queries of

‘hand washing’, ‘hand sanitizer’, and ‘disinfectant’,

respectively. Earlier increases in RSV tended to occur

in countries/regions with lower average number of daily cases. However, the heat map of ‘social

distancing’ did not display such a clear pattern; it

showed a sudden global increase in late March 2020

(online supplementary Fig c).

Discussion

Principal findings

Overview

The rapid and aggressive infectivity of COVID-19

requires the general public to be vigilant about

preventive measures. Although prevention is

generally preferred over curative treatment, the

effect of each preventive measure on COVID-19

transmission was unclear during early stages of

the pandemic. For example, during early stages of

the pandemic, there was controversy regarding the

importance of wearing masks to prevent COVID-19

transmission via droplets.34 Indeed, the routine use

of medical masks by normal healthy individuals

had not been recommended by the WHO at the

start of data collection.35 This controversy led to

confusion regarding public health policies, as well

as the stigmatisation of individuals who practised

specific preventive measures. Thus, the present

study retrospectively compared public awareness

of the five aforementioned preventive measures

with the progression of COVID-19; this analysis

was intended to provide guidance regarding public

health communication and policy decisions.

Early awareness in regions with low average

number of daily cases

The heat maps (online supplementary Figs a-d)

show a pattern of early awareness among countries/regions with lower average number of daily cases,

according to analyses of the queries ‘mask’, ‘hand

washing’, ‘hand sanitizer’, and ‘disinfectant’. These

findings suggested that such queries were associated

with the prevention of COVID-19 progression.

Despite these positive findings, we did not find

strong correlations between average number of daily

cases in specific countries/regions and the overall

geographical RSV trend throughout the study

period (Fig 2). This negative result highlighted the

importance of temporal element in the prevention

of COVID-19 transmission, implying that increased

public awareness in an earlier stage of the pandemic

was superior to an increase in the overall volume

of public awareness. Notably, a similar GT-based

study of mask awareness conducted earlier in May

2020 demonstrated a significant correlation (Kendall

rank correlation coefficient [τ] of -0.47) between

mask awareness and average RSV data during a very

early stage of the pandemic (21 January to 11 March

2020).36

Our positive findings regarding mask, hand washing, hand sanitiser, and disinfectant queries

are consistent with the current understanding

of COVID-19 transmission. The major routes

of COVID-19 transmission include contact,

droplets, and aerosols37; importantly, animate

and inanimate surfaces participate in COVID-19

transmission. Face masks may slow the spread of

COVID-19 by reducing aerosol and respiratory

droplet transmission.36 Systematic reviews and

meta-analyses have increasingly shown that mask

usage in community or healthcare settings reduces

COVID-19 transmission.38 39 40 41 42 43 In contrast, a Danish

randomised controlled trial of mask usage in the

general population suggested little to no evidence

that facemask usage alone could prevent transmission

of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2,

the virus causing COVID-19.44 Retrospective cohort

studies and case-control studies have provided some

evidence of the preventive effects of mask usage

in communities such as Beijing and Thailand.45 46

Additional randomised controlled trials are needed

to conclusively determine the benefits of mask usage

in the general population.47 Importantly, the routine

maintenance of good hand hygiene can reduce

contact transmission. The use of an alcohol-based

hand sanitiser can disrupt COVID-19 transmission

via surface protein precipitation.37 Our findings

regarding mask and hand washing queries were also

consistent with previous regional infodemiology

studies, including a Taiwanese GT-based study

focused on masks and hand washing.22 In support of

the regional results, the present study illustrated the

importance of early awareness on a global scale.

Despite the lack of a clear pattern of early

awareness concerning the search topic ‘social

distancing’, a meta-analysis has confirmed that

social distancing of ≥1 m reduces COVID-19

transmission.38 Therefore, the lack of positive findings

regarding ‘social distancing’ in the present study

does not necessarily indicate a lack of effectiveness.

Instead, it suggests inadequate public awareness.

Careful analysis of temporal RSV trends for all five

queries (Fig 1) revealed that a lower overall volume

of searches for ‘social distancing’. Although public

awareness of the topics ‘mask’, ‘hand sanitizer’, and

‘disinfectant’ may spontaneously increase because

of various other factors, such as a market shortage,

social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic

was often implemented via governmental policy,

rather than public awareness.48 49 This lack of public

awareness was demonstrated by the decrease

in confirmed COVID-19 cases in the US after

government-imposed social distancing measures

had been implemented.50 Despite their proven

efficacies, specific preventive measures such as hand

washing were often implemented via public health

initiatives, rather than law enforcement.48 49 Future

studies should seek to identify specific preventive measures beyond public awareness that can guide public health policy decisions regarding the COVID-19 pandemic.

Preventive measures against COVID-19

transmission are only effective if the majority of the

general public acknowledge and practise them with

the correct timing and knowledge. In addition to the

determination of whether a preventive measure is

effective, patterns of early public awareness should be

explored to enhance the preventive effects of public

health communication on COVID-19 transmission.

Effects of authorities, public figures, and social

media on public awareness

As mentioned above, there were multiple instances of a sudden surge in public awareness. One of the most

prominent patterns was the surge in ‘disinfectant’

queries on 24 April 2020. A substantial increase in

global awareness of disinfectant occurred within

a single day, leading to questions regarding the

underlying cause and whether that cause can provide

any insights concerning effective public health

communication. Further investigation revealed a

possible key event related to the timing and content

of the surge in ‘disinfectant’ queries: a speech made

by US President Donald Trump on 23 April 2020, in

which he claimed that disinfectant ‘knocks it [severe

acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2] out in a

minute’ and suggested that scientists should conduct

further research in this area.51 Although the scientific

legitimacy of the contents of Trump’s speech was

questionable, the speech itself had a substantial

impact on public awareness, as demonstrated by the

massive number of Google searches in such a short

period of time.

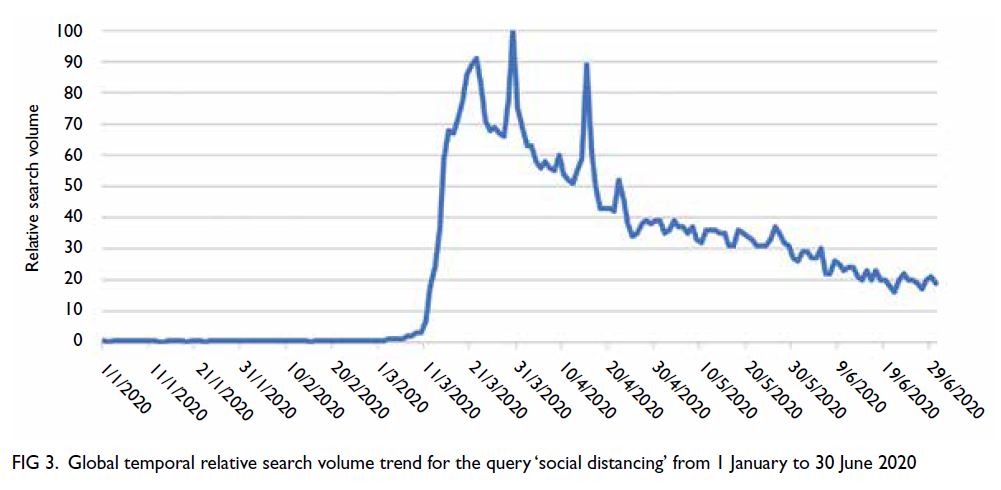

The example above was not the only surge

pattern evident in this study. Buried under the overwhelming search volumes of other queries,

the RSV magnitude of ‘social distancing’ appears

to be relatively negligible (Fig 1). However, closer

inspection of the temporal RSV trend of ‘social

distancing’ reveals an obvious surge from 10 March

2020 to 20 March 2020 (Fig 3). Over an interval of 10

days, the RSV of ‘social distancing’ increased from

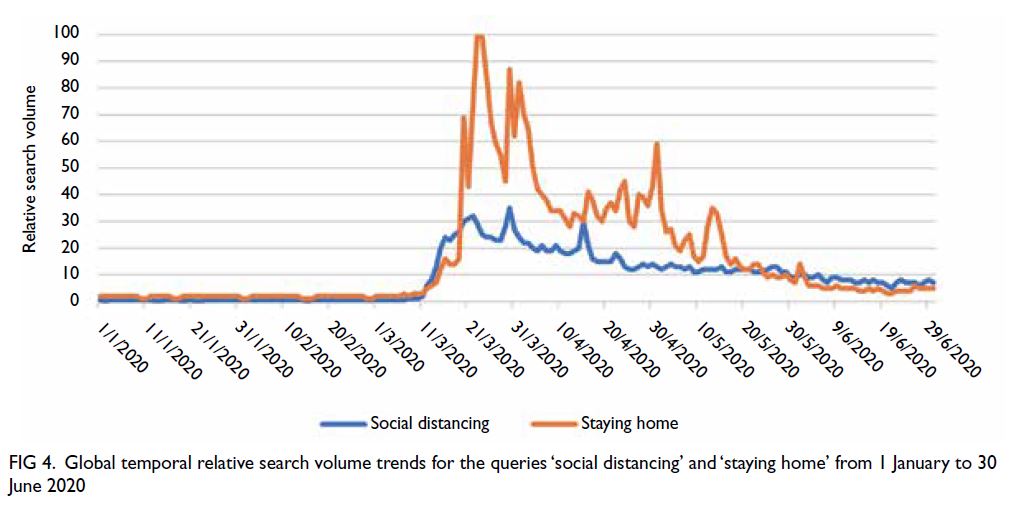

3 to 86. Similar to Trump’s speech, a key event in

early March was associated with the surge in ‘social

distancing’ queries. A sentiment of ‘staying home’

was reportedly coined by Florian Reifschneider, a

German engineer; it soon became a trend on social

media and was heavily promoted by prominent

celebrities.52 53 54 55 Although ‘staying home’ and ‘social

distancing’ are distinct key terms, an approximately

overlapping rise and fall pattern is evident upon

comparison of both RSV trends (Fig 4). Notably, the

RSV of ‘staying home’ overlapped with the RSV of

‘social distancing’, but the magnitude of the RSV of

‘staying home’ exceeded the magnitude of the RSV

of ‘social distancing’ by more than 50%; this finding

implies that the public response to social distancing

may have been greater if the concept of social

distancing had been promoted correctly.

Figure 3. Global temporal relative search volume trend for the query ‘social distancing’ from 1 January to 30 June 2020

Figure 4. Global temporal relative search volume trends for the queries ‘social distancing’ and ‘staying home’ from 1 January to 30 June 2020

The relationship between sudden surges in

global RSV and key events suggests that the effect of

global public awareness is secondary to promotion

by authorities and public figures. The evolution of

the internet and social media may offer new avenues

for public health communication, particularly in

times of crisis.

Limitations

There were a few limitations in this study. To begin with, GT data constitute an indirect representation of

public awareness; these data do not indicate whether

preventive measures were correctly implemented by the general public. Therefore, the analysis may

have overestimated or underestimated correlations.

Moreover, despite the use of search topics to explore

GT data, the selected keywords may not accurately

represent the concept of each preventive measure

because of variations in language, translation,

terminology, and spelling of the same concept.

Furthermore, to facilitate comparison, this study

exclusively analysed the queries in a single search

platform (ie, Google). This limited focus may have

led to sampling error based on access to Google, as

well as regional search engine preferences. Internet

accessibility also varies among regions; therefore, GT

data may not accurately represent public awareness

in regions with fewer internet users.

An important example is China (not including

Hong Kong), which was regarded as a country with

‘low search volume’ for some queries, despite its

538 million netizens.56 There are multiple reasons for

this bias. First, Google holds <20% of China’s online

search market; Baidu is the most popular search

engine.57 Future studies involving China should

consider the use of Baidu, as in a previous internet

query study specifically focused on China.57 However,

a study by Kang et al56 revealed that Chinese GT data

may be used as a valid complementary source of

information for influenza surveillance in south China.

Second, this study did not consider potential

confounders in the correlation analyses, including

the stringency of public health measures, the

containment capacities of the countries and regions

included, and the degree to which those countries and

regions are vulnerable to public health threats.58 59 60

Third, this study primarily focused on public

awareness and progression of COVID-19 in the early stages of the pandemic; thus, factors identified during later stages of the pandemic were not evaluated.

Finally, research concerning preventive

measures against COVID-19 is largely limited by the

lack of randomised controlled trials. Considering the

current scale of the pandemic, it is neither feasible

nor ethical to conduct individual randomised

controlled trials for each preventive measure in

healthcare or non-healthcare settings. Therefore,

infodemiology studies remain valuable in policy

making for the foreseeable future.

Conclusion

Google Trends offers large-scale population data

regarding public health events. The results of RSV

trend analysis revealed an earlier RSV peak in countries/regions with lower average number of daily cases,

suggesting that early public awareness can slow the

spread of a pandemic. During future pandemics,

global and local public health authorities could

focus on early public awareness to facilitate effective

disease control. Additionally, our findings illustrate

the value of early public health communication

regarding the use of masks, hand washing, hand

sanitiser, and disinfection among the general public

during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Author contributions

Concept or design: JYC Teoh, A Mok.

Acquisition of data: JYC Teoh, A Mok, OOY Mui.

Analysis or interpretation of data: JYC Teoh, A Mok, OOY Mui.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: JYC Teoh, A Mok, OOY Mui.

Analysis or interpretation of data: JYC Teoh, A Mok, OOY Mui.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As editors of the journal, CF Ng, MCS Wong and JYC Teoh were not involved in the peer review process. Other authors

have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet

2020;395:470-3. Crossref

2. World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s

opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19-11—March 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

3. Johns Hopkins University and Medicine. Coronavirus resource center. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

4. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

5. Eysenbach G. Infodemiology and infoveillance: framework

for an emerging set of public health informatics methods to

analyze search, communication and publication behavior

on the Internet. J Med Internet Res 2009;11:e11. Crossref

6. Chandrasekaran R, Mehta V, Valkunde T, Moustakas E. Topics, trends, and sentiments of tweets about the

COVID-19 pandemic: temporal infoveillance study. J Med

Internet Res 2020;22:e22624. Crossref

7. Alicino C, Bragazzi NL, Faccio V, et al. Assessing Ebola-related

web search behaviour: insights and implications

from an analytical study of Google Trends–based query

volumes. Infect Dis Poverty 2015;4:54. Crossref

8. Odlum M, Yoon S. What can we learn about the Ebola

outbreak from tweets? Am J Infect Control 2015;43:563-71. Crossref

9. van Lent LG, Sungur H, Kunneman FA, van de Velde B, Das E. Too far to care? Measuring public attention and fear for Ebola using Twitter. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e193. Crossref

10. Dugas AF, Jalalpour M, Gel Y, et al. Influenza forecasting with Google Flu Trends. PLoS One 2013;8:e56176. Crossref

11. Chew C, Eysenbach G. Pandemics in the age of Twitter: content analysis of Tweets during the 2009 H1N1 outbreak. PLoS One 2010;5:e14118. Crossref

12. Pruss D, Fujinuma Y, Daughton AR, et al. Zika discourse in

the Americas: a multilingual topic analysis of Twitter. PLoS

One 2019;14:e0216922. Crossref

13. Daughton AR, Paul MJ. Identifying protective

health behaviors on Twitter: observational study of

travel advisories and Zika virus. J Med Internet Res

2019;21:e13090. Crossref

14. Stefanidis A, Vraga E, Lamprianidis G, et al. Zika in Twitter: temporal variations of locations, actors, and concepts. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2017;3:e22. Crossref

15. Xue J, Chen J, Chen C, Hu R, Zhu T. The hidden pandemic

of family violence during COVID-19: unsupervised

learning of tweets. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e24361. Crossref

16. Chen X, Zhang SX, Jahanshahi AA, et al. Belief in a

COVID-19 conspiracy theory as a predictor of mental

health and well-being of health care workers in Ecuador:

cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Public Health Surveill

2020;6:e20737. Crossref

17. Rana U, Singh R. Emotion analysis of Indians using google

trends during COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab Syndr

2020;14:1849-50. Crossref

18. Chen E, Lerman K, Ferrara E. Tracking social media

discourse about the COVID-19 pandemic: development of

a public coronavirus Twitter data set. JMIR Public Health

Surveill 2020;6:e19273. Crossref

19. Effenberger M, Kronbichler A, Shin JI, Mayer G, Tilg H,

Perco P. Association of the COVID-19 pandemic with

internet search volumes: a Google TrendsTM analysis.

Int J Infect Dis 2020;95:192-7. Crossref

20. Hu D, Lou X, Xu Z, et al. More effective strategies are

required to strengthen public awareness of COVID-19:

evidence from Google Trends. J Glob Health

2020;10:011003. Crossref

21. Husain I, Briggs B, Lefebvre C, et al. Fluctuation of public

interest in COVID-19 in the United States: retrospective

analysis of Google Trends search data. JMIR Public Health

Surveill 2020;6:e19969. Crossref

22. Husnayain A, Fuad A, Su EC. Applications of Google

search trends for risk communication in infectious disease

management: a case study of the COVID-19 outbreak in

Taiwan. Int J Infect Dis 2020;95:221-3. Crossref

23. Rovetta A, Bhagavathula AS. COVID-19–related web

search behaviors and infodemic attitudes in Italy:

infodemiological study. JMIR Public Health Surveill

2020;6:e19374. Crossref

24. Chrzanowski J, Sołek J, Fendler W, Jemielniak D. Assessing

public interest based on Wikipedia’s most visited medical

articles during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: search trends

analysis. J Med Internet Res 2021;23:26331. Crossref

25. Google. FAQ about Google Trends data. Available from:

https://support.google.com/trends/answer/4365533?hl=en&dark=1. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

26. Mavragani A, Ochoa G. Google Trends in infodemiology

and infoveillance: methodology framework. JMIR Public

Health Surveill 2019;5:e13439. Crossref

27. World Health Organization. Advice for the public:

coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

28. Smallwood C, editor. The Complete Guide to Using Google in Libraries: Instruction, Administration, and Staff

Productivity. Volume 1. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield; 2015.

29. World Health Organization. Listings of WHO’s response to COVID-19. 2020; Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

30. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report–75. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200404-sitrep-75-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=99251b2b_4. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

31. World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s statement on IHR Emergency Committee on Novel

Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Available from: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-statement-on-ihr-emergency-committee-on-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

32. World Health Organization. Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) and considerations during severe shortages.

2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/rational-use-of-personal-protective-equipment-for-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-and-considerations-during-severe-shortages. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

33. Suthivarakom G. Coronavirus has caused a hand sanitizer shortage. What should you do? The New York Times. 11 March 2020. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/11/smarter-living/wirecutter/coronavirus-hand-sanitizer.html. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

34. Feng S, Shen C, Xia N, Song W, Fan M, Cowling BJ. Rational use of face masks in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:434-6. Crossref

35. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public: when and how to use masks. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/when-and-how-to-use-masks. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

36. Wong SH, Teoh JY, Leung CH, et al. COVID-19 and public interest in face mask use. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;202:453-5. Crossref

37. Pradhan D, Biswasroy P, Kumar Naik P, Ghosh G, Rath G. A review of current interventions for COVID-19 prevention. Arch Med Res 2020;51:363-74. Crossref

38. Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2020;395:1973-87. Crossref

39. Howard J, Huang A, Li Z, et al. An evidence review of face masks against COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

2021;118:e2014564118. Crossref

40. MacIntyre CR, Chughtai AA. A rapid systematic review of the efficacy of face masks and respirators against

coronaviruses and other respiratory transmissible viruses

for the community, healthcare workers and sick patients.

Int J Nurs Stud 2020;108:103629. Crossref

41. Tabatabaeizadeh SA. Airborne transmission of COVID-19 and the role of face mask to prevent it: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res 2021;26:1. Crossref

42. Fouladi Dehaghi B, Ghodrati-Torbati A, Teimori G, Ibrahimi Ghavamabadi L, Jamshidnezhad A. Face masks

vs. COVID-19: a systematic review. Invest Educ Enferm

2020;38:e13. Crossref

43. Li Y, Liang M, Gao L, et al. Face masks to prevent transmission of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control 2021;49:900-6. Crossref

44. Bundgaard H, Bundgaard JS, Raaschou-Pedersen DE, et al. Effectiveness of adding a mask recommendation to other

public health measures to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection

in Danish mask wearers: a randomized controlled trial.

Ann Intern Med 2021;174:335-43. Crossref

45. Wang Y, Tian H, Zhang L, et al. Reduction of secondary transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in households by face mask use, disinfection and social distancing: a cohort study in Beijing, China. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002794. Crossref

46. Doung-Ngern P, Suphanchaimat R, Panjangampatthana A,

et al. Case-control study of use of personal protective

measures and risk for SARS-CoV 2 infection, Thailand.

Emerg Infect Dis 2020;26:2607-16. Crossref

47. World Health Organization. Mask use in the context of COVID-19: Interim guidance, 1 December 2020. Available

from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/337199. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

48. International Monetary Fund. Policy responses to COVID-19. Available from: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

49. Mervosh S, Lu D, Swales V. See which states and cities have told residents to stay at home. The New York Times.

20 April 2020. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-stay-at-home-order.html. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

50. Courtemanche C, Garuccio J, Le A, Pinkston J, Yelowitz A. Strong social distancing measures in the United States reduced the COVID-19 growth rate. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39:1237-46. Crossref

51. Agence France-Presse. Experts rubbish Donald Trump’s

suggestion to inject disinfectant to kill coronavirus. South

China Morning Post. 24 April 2020. Available from: https://www.scmp.com/news/world/united-states-canada/article/3081503/experts-rubbish-trumps-suggestioninject?

module=perpetual_scroll&pgtype=article&campai

gn=3081503. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

52. American Medical Association. AMA, AHA, ANA: #StayHome to confront COVID-19. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-aha-ana-stayhome-confront-covid-19. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

53. Hudson A. Busy Philipps Joins Cameo to Record “Stay the Fuck Home” messages for coronavirus. Exclaim!. 17 March 2020. Available from: https://exclaim.ca/film/article/busy_philipps_joins_cameo_to_record_stay_the_fuck_home_messages_for_coronavirus. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

54. #StayTheFuckHome. A movement to stop the COVID-19 pandemic. Available from: https://staythefuckhome.com/. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

55. Ehrlich B. Taylor Swift urges fans to stay home amid COVID-19 outbreak. Rolling Stone. 15 March 2020. Available from: https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/taylor-swift-urges-fans-to-stay-home-amid-covid-19-outbreak-967629/. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

56. Kang M, Zhong H, He J, Rutherford S, Yang F. Using Google Trends for influenza surveillance in south China.

PLoS One 2013;8:e55205. Crossref

57. Yuan, Q, Nsoesie EO, Lv B, Peng G, Chunara R, Brownstein JS. Monitoring influenza epidemics in China with search query from Baidu. PLoS One 2013;8:e64323. Crossref

58. World Health Organization. e-SPAR State Party Annual Report. 2020. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/e-spar. Accessed 7 Sep 2020.

59. Wong MC, Huang J, Teoh J, Wong SH. Evaluation on different non-pharmaceutical interventions during COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of 139 countries. J Infect 2020;81:e70-1. Crossref

60. Wong MC, Teoh JY, Huang J, Wong SH. The potential impact of vulnerability and coping capacity on the pandemic control of COVID-19. J Infect 2020;81:816-46. Crossref