Hong Kong Med J 2023 Apr;29(2):132–41 | Epub 14 Apr 2023

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

The real-world impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with cancer: a multidisciplinary cross-sectional survey

Kelvin KH Bao, MB BChir, FRCR; Ka-man Cheung, MB, ChB, FRCR; James CH Chow, MB, ChB, FRCR; Carmen WL Leung, MB, ChB, FRCR; Kam-hung Wong, MB, ChB, FRCR

Department of Clinical Oncology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Corresponding author: Dr Kelvin KH Bao (bkh641@ha.org.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: The coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) pandemic has caused unprecedented

disruptions to cancer care worldwide. We conducted

a multidisciplinary survey of the real-world impact of

the pandemic, as perceived by patients with cancer.

Methods: A total of 424 patients with cancer were

surveyed using a 64-item questionnaire constructed

by a multidisciplinary panel. The questionnaire

examined patient perspectives regarding COVID-19–related effects (eg, social distancing measures)

on cancer care delivery, resources, and healthcare-seeking

behaviour, along with the physical and

psychosocial aspects of patient well-being and

pandemic-related psychological repercussions.

Results: Overall, 82.8% of respondents believed

that patients with cancer are more susceptible to

COVID-19; 65.6% expected that COVID-19 would

delay anti-cancer drug development. Although only

30.9% of respondents felt that hospital attendance

was safe, 73.1% expressed unaltered willingness

to attend scheduled appointments; 70.3% of

respondents preferred to receive chemotherapy

as planned, and 46.5% were willing to accept

changes in efficacy or side-effect profile to allow

an outpatient regimen. A survey of oncologists

revealed significant underestimation of patient motivation to avoid treatment interruptions. Most

surveyed patients felt that there was an insufficient

amount of information available concerning the

impact of COVID-19 on cancer care, and most

patients reported social distancing–related declines

in physical, psychological, and dietary wellness. Sex,

age, education level, socio-economic status, and

psychological risk were significantly associated with

patient perceptions and preferences.

Conclusion: This multidisciplinary survey concerning the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic

revealed key patient care priorities and unmet needs.

These findings should be considered when delivering

cancer care during and after the pandemic.

New knowledge added by this study

- Most patients with cancer (73.1%) reported that their willingness to attend scheduled oncology appointments was not affected by the pandemic. All surveyed oncologists underestimated patient motivation to avoid treatment interruptions.

- Patient acceptance of telerehabilitation varied according to age and socio-economic status, whereas the negative impact of social distancing on patients with cancer were substantial and multidimensional.

- Psychometric analyses can stratify patients with cancer into psychological risk groups, based on their distinct perceptions of the pandemic.

- These findings will help to increase awareness of the effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on patients with cancer, revealing their priorities and unmet needs.

- This work aligns the expectations of oncologists and patients with cancer with respect to modifications of cancer services during the pandemic.

- These results will promote better resource allocation and earlier multidisciplinary interventions to reduce pandemic-related impact on at-risk populations.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic

poses an unprecedented threat to health systems

worldwide. During the first year of the pandemic, there were more than 110 million confirmed

COVID-19 cases globally and more than 2.6 million

deaths.1 In terms of scale, the number of COVID-19

cases during that period was at least sixfold more than the global number of new cancer cases in 2018; the

mortality during that period exceeded the combined

mortalities of lung cancer and breast cancer in

2018.2 The many consequences of COVID-19 have

included unprecedented disruptions to cancer

care services,3 4 5 such as cancellations of outpatient

appointments to delays in scheduled systemic

treatments and radiotherapy; during periods of

increased transmission, such disruptions have forced

oncologists to make difficult decisions in attempts to

balance patient protection and disease control. There

have been similar impact to the delivery of oncology-related

allied health services, including physical

therapy and occupational therapy,6 dietetics,7

diagnostic imaging,8 and psychological services for patients with cancer9; there has been a particularly large shift in the use of telemedicine. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, and particularly

during periods of increased transmission, good

multidisciplinary coordination has been a crucial

aspect of cancer care. By acquiring comprehensive

knowledge regarding perceptions of the pandemic,

changes in healthcare-seeking behaviour, impact

on daily life, and the newly emerged unmet needs

(physical, socio-economic, and psychological)

of patients with cancer, multidisciplinary cancer

caregivers can customise and adjust their services

accordingly, thus enabling appropriate resource

allocation. Considering these challenges, we

designed and conducted a prospective study to comprehensively examine the real-world impact of

COVID-19 on patients with cancer; we sought to

identify actionable solutions from the perspective of

experienced multidisciplinary cancer caregivers.

Methods

A prospective survey regarding the perspectives

of patients with cancer on the impact of the

COVID-19 pandemic was jointly developed by

a multidisciplinary team at Queen Elizabeth

Hospital, Hong Kong that consisted of clinical

oncologists, clinical psychologists, physiotherapists,

occupational therapists, and dieticians specialising

in cancer care. A pilot survey was administered

to 88 patients, followed by interviews to further

assess patient understanding of the questions

and to develop additional items via thematic

analysis. The multidisciplinary team then refined

the questionnaire. The final version consisted of

64 items with a combination of Likert scales and

polar questions; it covered topics such as patient

perceptions of cancer care resources, treatment

delivery and quality, changes in healthcare-seeking

behaviour, adequacy of available pandemic-related

information, social distancing–related adverse

impact, and psychological repercussions of the

pandemic. We also invited patients who were newly

diagnosed with cancer to complete an extended

questionnaire which focused on psychometric

measurements of post-traumatic stress disorder

(PTSD) [the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)],10 anxiety and depression (the Emotion Thermometers

tool),11 and intolerance of uncertainty (the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-12 [IUS-12]).12 Patients were then stratified into risk groups. High-risk

individuals had scores of ≥5 on the abbreviated

PCL-5 scale,13 ≥3 on the Emotion Thermometers for depression or anxiety,14 and ≥25 on the IUS-12

scale.11 Associations between patient perceptions

and psychological risk were then explored. Full

details of the patient questionnaire are shown in

online supplementary Table 1.

Furthermore, we surveyed clinical oncologists

in Hong Kong (practising in Queen Elizabeth

Hospital, United Christian Hospital, and Buddhist

Hospital) regarding their perceptions of the

pandemic; the oncologists were also asked to predict

the responses of patients with cancer in various

domains of interest.

The patient survey was conducted between

12 and 22 May 2020 at Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

Patients with cancer and survivors aged ≥18 years

who attended their outpatient oncology appointments

were invited to participate. Patients who could

not read English or Chinese were excluded, and

participation was voluntary. Detailed survey

information was provided on the questionnaire

cover sheet, and a patient’s decision to participate in the survey was regarded as informed consent.

Hardcopies of the questionnaire were anonymously

completed by participants on site, then collected by

dedicated nursing staff.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to describe various

impact of the pandemic on patients. Patient

demographics, disease characteristics, treatment

details, and socio-economic information were

summarised. Qualitative data are presented as the

percentage of respondents who selected a particular

response. Chi squared tests were used to determine

associations between responses and categorical

patient factors. P values <0.05 were considered

indicative of statistical significance. Analyses were

performed using SPSS software (Windows version

25.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

Results

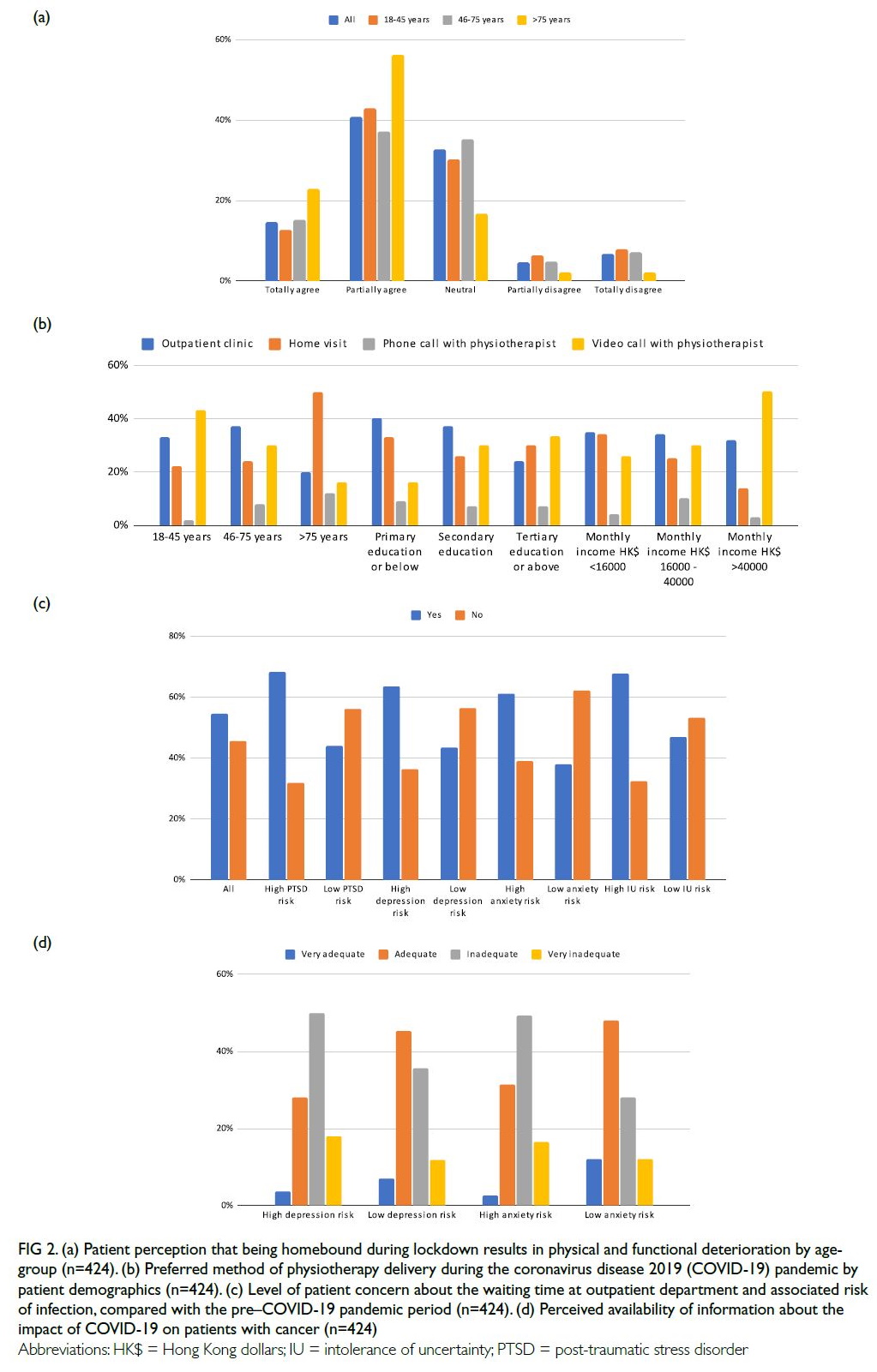

Demographic characteristics

Between 12 and 22 May 2020, 650 patients with

cancer were invited to participate in the survey; 424

responses were received, yielding a response rate of

65.2%. Demographic and clinical characteristics of

the participants are presented in the Table. Most

survey respondents were female (70.0%), and more

than half were aged 46 to 75 years. Nearly half (46.0%)

of the respondents were receiving active cancer

treatment. The cancer stage was III or below in half

of the respondents and 20.3% of respondents were

at stage IV; 29.2% of respondents were uncertain of

their staging. Almost half (43.9%) of the respondents

had a monthly family income of <HK$16 000 (around

US$2000), which is Hong Kong’s 2018 poverty line

for a family of three.15

Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on cancer

resources

As shown in online supplementary Table 1, most

respondents (82.8%) believed that patients with

cancer are more susceptible to COVID-19, while

more than half (52.1%) believed that cancer-related

resources will be depleted and 59.3% were

concerned that healthcare workforce shortages

during the pandemic would harm their treatment.

Overall, 65.6% of respondents were concerned that

COVID-19 would lead to delays in anti-cancer drug

development. These concerns were significantly

associated with education level of patients, in which

the more educated respondents demonstrated less

concern (tertiary level 57.6% vs secondary 64.4% vs

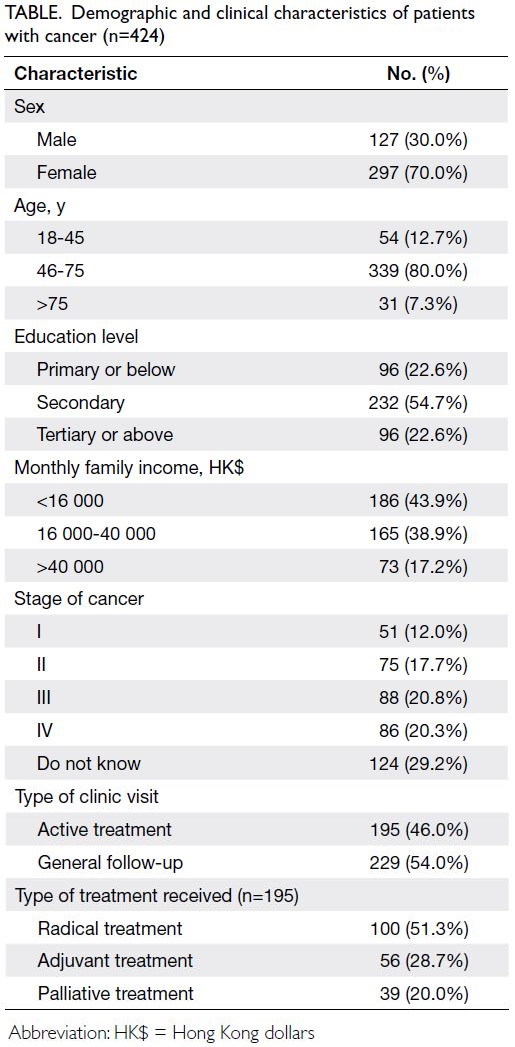

primary 71.4%, P=0.01) [Fig 1a].

Figure 1. (a) Level of patient concern about the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on anti-cancer drug development by education level (n=424). (b) Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on patient willingness to attend hospital appointments by patient demographics (n=424). (c) Perceived availability of information about the impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer by education level (n=424)

Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on

healthcare-seeking behaviour

As shown in online supplementary Table 1, fewer than one-third of respondents (30.9%) felt that it

was safe to attend hospital appointments during the

pandemic (the proportion was greater among men

than among women: 37.8% vs 27.8%). Furthermore,

most respondents reported that their willingness

to attend oncology clinic appointments (73.1%)

or undergo clinical tests (80.2%) was unaffected.

Age (P=0.021), sex (P=0.029), and education level

(P=0.003) were factors significantly associated with

patient willingness; respondents aged 18-45 years

or >75 years, female, and more educated individuals

were more hesitant to attend their scheduled

appointments (Fig 1b).

Compared with the pre-pandemic period,

most respondents (79.0%) stated that they were

equally willing (65.1%) or more willing (13.9%)

to seek medical attention now if they felt unwell.

Overall, 62.2% of respondents were equally willing or more willing to be hospitalised if requested by their

oncologists. Male respondents were more willing to

be hospitalised, compared with female respondents

(68.3% vs 59.2%); additionally, respondents

receiving radical treatment were more willing to be

hospitalised, compared with respondents receiving

palliative treatment (71.3% vs 59.0%).

Effects of social distancing on medical

consultation and cancer treatment

Nearly all respondents (98.4%) felt that it was

acceptable for medical staff to maintain an increased

physical distance from patients during consultations,

and most (83.3%) felt that it did not negatively

impact the quality of their clinic experience. During

the pandemic, some clinically stable patients

were exempt from the requirement for oncologist

examination prior to medication refills. Overall,

59.9% of respondents felt that such an arrangement

should continue beyond the pandemic period

(male respondents vs female respondents: 69.3% vs

55.9%; respondents receiving radical treatment vs

respondents receiving palliative treatment: 54.4% vs

69.2%).

Concerning the effects of the pandemic on

plans for cancer treatment, most respondents stated

that their decisions to receive chemotherapy (70.3%)

or radiotherapy (67.9%) were unaffected. However,

46.5% of the respondents were willing to accept

changes in treatment efficacy or side-effect profile

to allow an outpatient regimen; this preference was

particularly strong among respondents receiving

palliative treatment (61.5%), compared with

respondents receiving radical treatment (33.7%).

Acquisition and adequacy of pandemic-related

information

As shown in online supplementary Table 1, half of

the respondents (49.1%) spent an average of 10 to 30

minutes daily interacting with news and information

sources focused on COVID-19. Their most common

news sources were television (41.7%), the internet

(28.0%), and newspapers (12.9%). Only 3.5% of

respondents received pandemic-related news or

information from their hospitals. Young respondents

(<45 years) were significantly more likely to receive

news primarily from the internet, compared with

older respondents (>75 years) (37.6% vs 13.4%;

P=0.001); such a difference was also present between

respondents with different education levels (tertiary

education vs primary education: 35.5% vs 17.4%;

P=0.001) and between respondents with different

levels of monthly family income (>HK$40 000 vs

<HK$16 000: 32% vs 25%; P=0.006).

Concerning the adequacy of information

received regarding COVID-19 and its impact

on patients with cancer, more than half of the respondents (54.1%) felt that it was inadequate; this

sentiment was more prevalent among respondents

with a higher education level, compared with those

who were less educated (tertiary vs primary level:

60.2% vs 40.3%; P=0.017) [Fig 1c].

Effects of social distancing on allied health

professional services

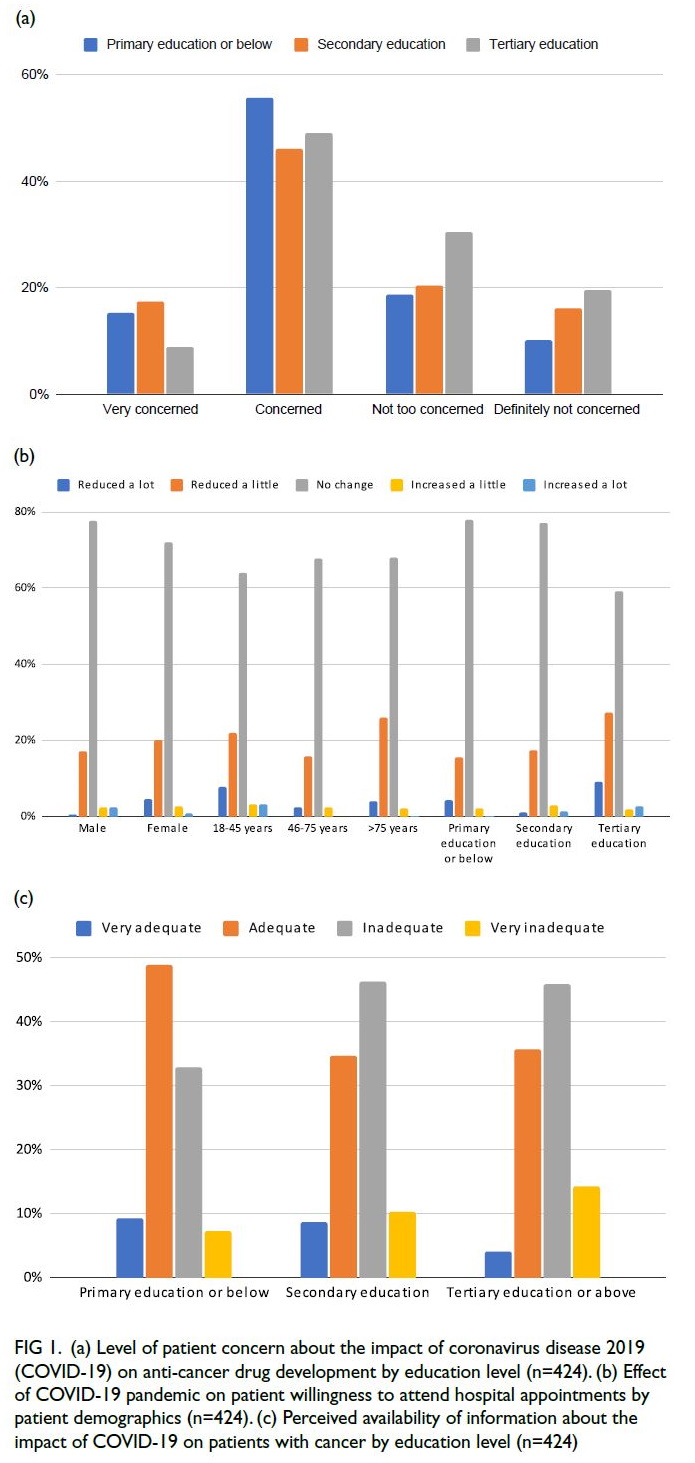

During the pandemic, social distancing became

the new daily norm. Nearly half of the respondents

(49.5%) reported exercising less, whereas 10.4%

reported exercising more. In general, 55.4% of

respondents noticed an overall deterioration in

their physical well-being (Fig 2a); about one-third

of respondents (32.1%) reporting reduced walking

tolerance, and 25.9% of respondents noticed some

reduction in limb power (online supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2. (a) Patient perception that being homebound during lockdown results in physical and functional deterioration by age-group (n=424). (b) Preferred method of physiotherapy delivery during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic by patient demographics (n=424). (c) Level of patient concern about the waiting time at outpatient department and associated risk of infection, compared with the pre–COVID-19 pandemic period (n=424). (d) Perceived availability of information about the impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (n=424)

With respect to patient preferences regarding

physiotherapy delivery during the pandemic, 42.9%

of young respondents (18-45 years) preferred online

sessions, whereas 50.0% of older respondents (>75

years) preferred home visits by a therapist [Fig 2b].

Education level (P=0.029) and income (P=0.034)

were significantly associated with patient preference.

Respondents with a higher education level (tertiary

vs primary level: 33.3% vs 16.3%) and respondents

with a higher income (monthly income >HK$40 000

vs <HK$16 000: 50.3% vs 26.0%) preferred online

sessions, rather than in-person sessions.

During the period of social distancing, 64.5%

of older respondents (>75 years) felt that their lives

had become monotonous and lonely; significantly

fewer (39.3%) younger respondents (<45 years)

expressed this sentiment. Most respondents (58.0%)

agreed that their home care support had improved

because family members spent more time together;

this sentiment was more prevalent among older

respondents (>75 years) [70.9%].

As shown in online supplementary Table 1,

the pandemic caused dietary habit alterations in

38.9% of respondents. Approximately one-fifth of

respondents reported reduced appetite (22.2%) and

increased consumption of junk food (processed

or ready-made meals) (19.3%). Significantly more

respondents in the low-income subgroup reported

reduced appetite, compared with respondents in

the high-income subgroup (30.6% vs 8.2%, P=0.001).

Notably, the use of face masks led to a reduction in

meal frequency among 30.7% of respondents; this

reduction was more prevalent among respondents

with lower income, compared with respondents who

had higher income (32.6% vs 23.2%).

Psychological impact of coronavirus disease

2019

Overall, 41.0% and 23.1% of respondents had recently experienced anxiety and/or depressed mood. In total,

103 consecutive newly diagnosed patients responded

to the extended psychometric questionnaire. The

results revealed greater levels of concern regarding

the impact of COVID-19 on cancer care manpower

and the risk of infection during outpatient clinic

waiting time in patients with higher risks of PTSD

(P=0.011 and P=0.015, respectively), anxiety

(P=0.013 and P=0.034, respectively), depression

(P=0.017 and P=0.043, respectively), and uncertainty

intolerance (P=0.004 and P=0.044, respectively) [Fig 2c]. A high IUS-12 score (uncertainty intolerance)

was associated with the presence of greater concern

regarding the effects of the pandemic on cancer

research and drug development (P=0.03). As shown

in online supplementary Table 2, respondents with

a high risk of anxiety were less likely to agree with

the ‘no visiting’ policy of hospitals (P=0.013). More

respondents with high risks of anxiety (P=0.024)

and depression (P=0.044) felt that there was an

insufficient amount of information available in the

media regarding the impact of COVID-19 on patients

with cancer (Fig 2d). Moreover, respondents with a

high risk of PTSD demonstrated significantly greater

concern when asked about their fear of being infected

by their caregiver or family members, compared with

respondents who had a low risk of PTSD (P=0.005).

Detailed results of the psychometric questionnaire

are shown in online supplementary Table 2.

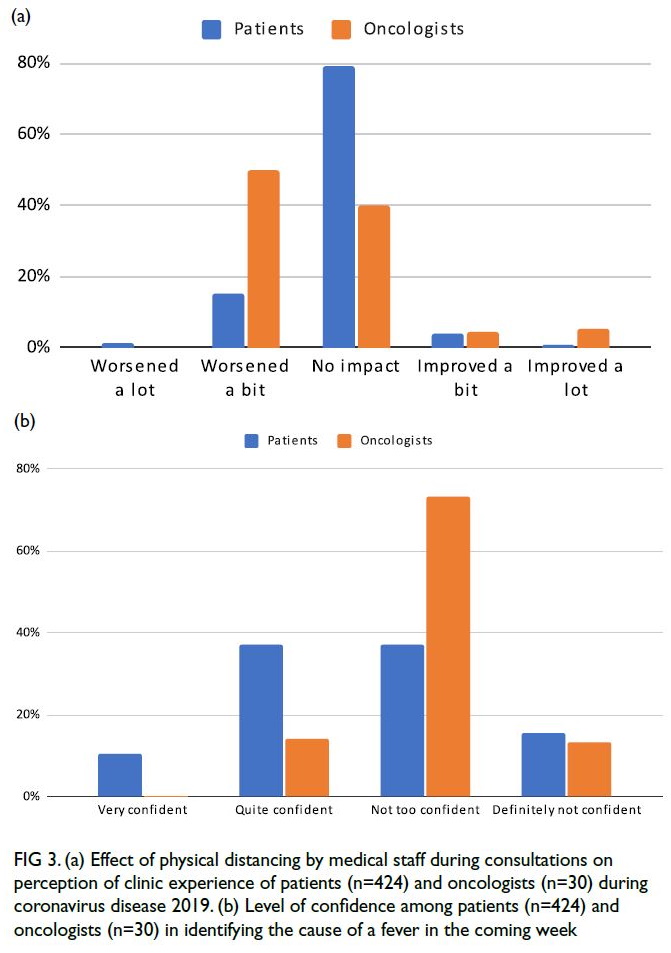

Comparison of oncologist and patient

perspectives

We invited 30 practising clinical oncologists to predict patient healthcare-seeking behaviour during the

pandemic. All 21 responding oncologists predicted

significant reductions in patient willingness to

attend appointments and patient willingness to be

hospitalised, but most patients reported no change

in either type of willingness (73.3% and 54.7%,

respectively). A greater proportion of oncologists

(50.0%) than patients (16.7%) reported a negative

impact on their clinic experience because of doctor-patient

distancing measures (Fig 3a). Furthermore,

when asked about their confidence in identifying the

cause of a new fever (COVID-19–related vs other

causes), most oncologists reported little (73.3%) or

no confidence (13.3%), whereas almost half of the

patients (47.4%) reported that they were quite or

very confident in their ability to identify the cause of

a new fever (Fig 3b).

Figure 3. (a) Effect of physical distancing by medical staff during consultations on perception of clinic experience of patients (n=424) and oncologists (n=30) during coronavirus disease 2019. (b) Level of confidence among patients (n=424) and oncologists (n=30) in identifying the cause of a fever in the coming week

Discussion

This study investigated the perceptions of patients

with cancer regarding the real-world impact of

COVID-19 (during the early days of the pandemic)

through the perspective of a multidisciplinary

team that included clinical oncologists, clinical psychologists, physiotherapists, dieticians, and

occupational therapists. Using a comprehensive

set of questions, we identified key concerns, unmet

needs, perceptions, and expectations of patients

with cancer at different stages in their cancer care

journeys. Cancer care16 and pandemic management17

are both resource-intensive endeavours. Because

the COVID-19 pandemic has become the focus

of healthcare worldwide, it is understandable

that patients with cancer are concerned about

pandemic-related negative impact on cancer care

resources. Our results suggest that patients with

cancer remained committed to attending scheduled

appointments, despite the perceived risk of

COVID-19 during the early days of the pandemic.

This sustained clinical demand—along with general

acceptance among patients regarding COVID-19

adaptive measures (staff-patient distancing),

streamlined services (prescription-only clinics),

and outcome trade-offs (efficacy and side-effect

profile)—allowed our oncology services to continue

with minimal disruptions despite the reduced

availability of healthcare resources. Nevertheless,

only 30.9% of surveyed patients felt that it was safe

to attend the hospital; this observation highlights the

need to ensure patients are informed about hospital

safety measures for COVID-19 management,

with details regarding rationale and efficacy. This

study also revealed a discrepancy between male

and female patients in terms of healthcare-seeking

behaviour; moreover, patients receiving radical

treatment demonstrated different perceptions and

needs, compared with patients receiving palliative

care. Oncology healthcare providers should consider

the unique needs of various patient groups when

implementing pandemic management strategies.

Between the initial outbreak and the time of

this survey, the general public’s understanding of

COVID-19 heavily relied on mainstream media

coverage,18 which often did not focus on the needs

of specific patient groups. International guidelines

regarding cancer management during the pandemic

began to emerge later in 2020,19 but they mainly targeted medical professionals. Accordingly,

patients with cancer felt that the COVID-19–related

information provided to patients was inadequate.

This perception was particularly prevalent among

patients with a higher education level, who tended to

obtain news and information more frequently from

multiple sources (eg, the internet and social media).

Notably, this situation highlights the phenomenon

of ‘the more you know, the more you realise you

don’t know’, thereby emphasising the presence of an

additional information barrier for underprivileged

patient groups.20 The situation is further

complicated by the presence of COVID-19–related

misinformation, which has been widespread on

social media since 2020.21 The findings in this study provide insights concerning the distinct pandemic-related

information preferences and needs among

patients according to age, education level, and

income. Cancer services should focus on addressing

these preferences and needs by providing patients

with current COVID-19–related information from

official sources, ensuring that the hospital remains

a source of verified and practical pandemic-related

information accessible to all patients.

The consequences of social distancing (eg,

reduced exercise, poor diet, increased financial

burden, and loss of social interactions) are

detrimental to the physical and psychological well-being

of patients with cancer,22 23 24 potentially reducing

cancer treatment tolerance and compromising

outcomes. Although the impact of pandemic-related

lockdowns on dietary patterns of diabetic patients25 and older population26 have been studied,

there are limited prospective data regarding the

nutritional status of patients with cancer and their

needs during the pandemic. This study has revealed

some real-world patient needs, particularly among

socio-economically disadvantaged patients; it also

highlights the importance of individualised dietetic

and occupational health assessments and early

interventions (inpatient or outpatient) by dieticians

and occupational therapists who specialise in cancer

care. Dedicated self-help materials prepared by

allied health professionals to address the adverse

effects of social distancing may also serve as effective

resources.

When the pandemic began, telerehabilitation

emerged as a promising alternative method for

patient–clinician interactions, with effective use in

a physiotherapy context.27 28 However, our findings

indicate that telerehabilitation may not be universally

welcomed, particularly among older patients. Turolla

et al29 described the challenges of implementing

telerehabilitation; our findings highlight the need

to carefully examine telemedicine accessibility and

‘telehealth literacy’30 among socio-economically underprivileged populations.31 32 When possible,

conventional physiotherapy and rehabilitation

should remain available, particularly for older

adults, less-educated individuals, and low-income

patients.33 Our findings offer a rationale for triaging

appropriate patients towards telemedicine; they

also highlight the need for improving telemedicine

quality and access, as well as the importance of

ensuring that alternatives are available.

This study demonstrated that psychometric

analysis is a meaningful tool for identifying at-risk

populations of patients with cancer during the

pandemic. Patients in psychological high-risk

groups clearly demonstrated distinct perceptions,

expectations, and needs when simultaneously

confronted with a cancer diagnosis and the

COVID-19 pandemic. Without effective

management, such patients could experience long-lasting

psychiatric morbidities, as revealed during

the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic in

2003.34 35 Wang et al36 emphasised the importance

of mental healthcare attention and resources

for patients with cancer during the COVID-19

pandemic. Along with routine cancer care, targeted

psychotherapies and follow-up care for both the

acute impact and long-term sequelae of COVID-19

are needed.

Oncologists and patients with cancer have

different perceptions of cancer symptoms, treatment

priorities, and psychosocial needs.37 38 39 We found

that oncologists tended to underestimate patient

motivation to avoid treatment interruptions, as

well as patient risk acceptance, consistent with the

observation by Catania et al40 that patients with cancer were more concerned about their cancers

than about the pandemic. Moreover, compared with

oncologists, a greater proportion of our surveyed

patients expressed confidence in identifying

COVID-19 symptoms. These results illustrate

differences in priorities and perceptions of pandemic

severity, along with the challenge of balancing

disruptions to cancer treatment and maintaining

COVID-19–related safety.

Proposed interventions to minimise the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on cancer patients

The following are some proposed interventions

to minimise the impact of COVID-19 on cancer patients:

1. Ensure that patients are informed about hospital safety measures for COVID-19 management, with details regarding rationale and efficacy.

2. Ensure that healthcare staff maintain appropriate physical distance from patients.

3. Operate prescription-only clinics and lengthen follow-up intervals for clinically stable patients.

4. Triage appropriate patients towards telemedicine; enhance general telehealth literacy by implementing user-friendly interfaces, step-by-step demonstrations, and support hotlines.

5. Establish a regularly updated COVID-19–related newsfeed that is customised for patients with cancer.

6. Work with dieticians, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists to create self-help pamphlets that can guide patients with cancer in coping with the effects of social distancing; facilitate the establishment of virtual support groups for patients with cancer.

7. Implement early allied health assessments and interventions for at-risk patients.

8. Ensure early psychological support, particularly for newly diagnosed patients.

9. Compassionately and flexibly enforce restrictive measures for newly diagnosed patients, individuals approaching the end of life, and selected at-risk patients.

10. Periodically review these measures as the pandemic progresses.

1. Ensure that patients are informed about hospital safety measures for COVID-19 management, with details regarding rationale and efficacy.

2. Ensure that healthcare staff maintain appropriate physical distance from patients.

3. Operate prescription-only clinics and lengthen follow-up intervals for clinically stable patients.

4. Triage appropriate patients towards telemedicine; enhance general telehealth literacy by implementing user-friendly interfaces, step-by-step demonstrations, and support hotlines.

5. Establish a regularly updated COVID-19–related newsfeed that is customised for patients with cancer.

6. Work with dieticians, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists to create self-help pamphlets that can guide patients with cancer in coping with the effects of social distancing; facilitate the establishment of virtual support groups for patients with cancer.

7. Implement early allied health assessments and interventions for at-risk patients.

8. Ensure early psychological support, particularly for newly diagnosed patients.

9. Compassionately and flexibly enforce restrictive measures for newly diagnosed patients, individuals approaching the end of life, and selected at-risk patients.

10. Periodically review these measures as the pandemic progresses.

Study strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies

to simultaneously explore perceptions of the real-world

impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among

patients with cancer and oncologists. Importantly,

the efforts of the multidisciplinary team to construct

the questions contributed to a multidimensional,

holistic understanding of issues and unmet needs

that affect patients with cancer at different stages of

their cancer care journeys. Because of the in-person

survey invitation and paper-and-pen methodology, our survey achieved a high response rate of 65%,

ensuring that the results are representative of the

surveyed population. However, sampling bias was

present because survey respondents were patients

who physically attended their clinic appointments;

data were missing for around 10% of patients

who declined to attend their clinic appointments.

Furthermore, this survey was conducted within a

short interval (2 weeks) towards the end of the first

wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong,

when there was a gradual easing of lockdown policies

and personal protective equipment availability began

to improve41; thus, this cross-sectional assessment

may not adequately reflect the evolution of patient

perceptions regarding the COVID-19 pandemic.

Other key limitations of the study include its

inclusion of patients from a single cancer centre, as

well as the exclusion of patients who could not read

Chinese or English and patients who underwent

treatment in private clinics. There is a need to repeat

the study at various time points throughout the

pandemic; future analyses should focus on other

affected countries and patient populations.

Conclusion

This multidisciplinary survey concerning the effects

of the COVID-19 pandemic impact revealed key

care priorities among patients with cancer, as well

as their unmet needs; in particular, it highlighted the

importance of distinct priorities and needs among

socio-economically underprivileged groups and

patients with diverse psychological phenotypes.

Oncologists should be aware that their own

perceptions of pandemic-related effects differ from

their patients’ perceptions. These findings should

be carefully considered as multidisciplinary teams

modify their delivery of cancer care services during

and after the pandemic.

Author contributions

Concept or design: KKH Bao, KM Cheung, JCH Chow.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KKH Bao, KM Cheung, JCH Chow.

Drafting of the manuscript: KKH Bao, KM Cheung, JCH Chow.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: KKH Bao, KM Cheung, JCH Chow.

Drafting of the manuscript: KKH Bao, KM Cheung, JCH Chow.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank all multidisciplinary team members and

participating patients for their efforts and contributions.

Declaration

This research has been presented in part as poster

presentations at the following conferences:

1. ESMO Congress 2020, virtual, 19-21 Sep 2020 (title: Cancer patients’ perspectives on the real-world impact of COVID-19 pandemic: a multidisciplinary survey)

2. ESMO Asia Congress 2020, virtual, 20-22 Nov 2020 (title: Psychometric interplay of the perception of the real-life impact of COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey of patients with newly diagnosed malignancies)

1. ESMO Congress 2020, virtual, 19-21 Sep 2020 (title: Cancer patients’ perspectives on the real-world impact of COVID-19 pandemic: a multidisciplinary survey)

2. ESMO Asia Congress 2020, virtual, 20-22 Nov 2020 (title: Psychometric interplay of the perception of the real-life impact of COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey of patients with newly diagnosed malignancies)

Funding/support

This research was supported by the Hong Kong Hospital

Authority Kowloon Central Cluster Research Grant 2020 (Ref No.: KCC/RC/G/2021-B01).

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Kowloon Central/Kowloon

East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Hospital

Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: KC/KE-20-0126/ER-1). All

eligible respondents explicitly agreed to join the panel and

provided informed consent to participate in the study.

References

1. World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available from: https://covid19.who.int. Accessed 7 Nov 2020.

2. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424. Crossref

3. Jazieh AR, Akbulut H, Curigliano G, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care: a global collaborative

study. JCO Glob Oncol 2020;6:1428-38. Crossref

4. Chen-See S. Disruption of cancer care in Canada during COVID-19. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:e374. Crossref

5. Sud A, Torr B, Jones ME, et al. Effect of delays in the

2-week-wait cancer referral pathway during the COVID-19

pandemic on cancer survival in the UK: a modelling study.

Lancet Oncol 2020;21:1035-44. Crossref

6. Prvu Bettger J, Thoumi A, Marquevich V, et al. COVID-19: maintaining essential rehabilitation services across the

care continuum. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002670. Crossref

7. Thibault R, Coëffier M, Joly F, Bohé J, Schneider SM, Déchelotte P. How the Covid-19 epidemic is challenging

our practice in clinical nutrition—feedback from the field.

Eur J Clin Nutr 2021;75:407-16. Crossref

8. Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in

diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based,

modelling study. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:1023-34. Crossref

9. Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet

Psychiatry 2020;7:e17-8. Crossref

10. Price M, Szafranski DD, van Stolk-Cooke K, Gros DF. Investigation of abbreviated 4 and 8 item versions of the

PTSD Checklist 5. Psychiatry Res 2016;239:124-30. Crossref

11. Beck KR, Tan SM, Lum SS, Lim LE, Krishna LK. Validation of the emotion thermometers and hospital anxiety and

depression scales in Singapore: screening cancer patients

for distress, anxiety and depression. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2016;12:e241-9. Crossref

12. Carleton RN, Norton MA, Asmundson GJ. Fearing the unknown: a short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty

Scale. J Anxiety Disord 2007;21:105-17. Crossref

13. Geier TJ, Hunt JC, Hanson JL, et al. Validation of abbreviated four- and eight-item versions of the PTSD

checklist for DSM-5 in a traumatically injured sample. J

Trauma Stress 2020;33:218-26. Crossref

14. Schubart JR, Mitchell AJ, Dietrich L, Gusani NJ. Accuracy of the Emotion Thermometers (ET) screening tool in patients undergoing surgery for upper gastrointestinal malignancies. J Psychosoc Oncol 2015;33:1-14. Crossref

15. Office of the Government Economist Financial Secretary’s

Office. Census and Statistics Department. Hong Kong SAR Government. Hong Kong Poverty Situation Report 2018.

Available from: https://www.povertyrelief.gov.hk/eng/pdf/Hong_Kong_Poverty_Situation_Report_2018(2019.12.13).pdf. Accessed 17 Mar 2023.

16. Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States:

2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:117-28. Crossref

17. Tan-Torres Edejer T, Hanssen O, Mirelman A, et al. Projected health-care resource needs for an effective response to COVID-19 in 73 low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e1372-9. Crossref

18. Casero-Ripollés A. Impact of Covid-19 on the media system. Communicative and democratic consequences of

news consumption during the outbreak. El profesional de

la información 2020;29:e290223. Crossref

19. Curigliano G, Banerjee S, Cervantes A, et al. Managing cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: an

ESMO multidisciplinary expert consensus. Ann Oncol

2020;31:1320-35. Crossref

20. Matsuyama RK, Wilson-Genderson M, Kuhn L, Moghanaki D, Vachhani H, Paasche-Orlow M. Education

level, not health literacy, associated with information needs

for patients with cancer. Patient Educ Couns 2011;85:e229-36. Crossref

21. Pennycook G, McPhetres J, Zhang Y, Lu JG, Rand DG. Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media:

experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy-nudge

intervention. Psychol Sci 2020;31:770-80. Crossref

22. Di Corrado D, Magnano P, Muzii B, et al. Effects of social distancing on psychological state and physical activity

routines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sport Sci Health

2020;16:619-24. Crossref

23. Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour

and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19

International Online Survey. Nutrients 2020;12:1583. Crossref

24. Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the

need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern

Med 2020;180:817-8. Crossref

25. Ruiz-Roso MB, Knott-Torcal C, Matilla-Escalante DC, et al. COVID-19 lockdown and changes of the dietary pattern

and physical activity habits in a cohort of patients with type

2 diabetes mellitus. Nutrients 2020;12:2327. Crossref

26. Ceolin G, Moreira JD, Mendes BC, Schroeder J, Di Pietro PF, Rieger DK. Nutritional challenges in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic [in Spanish]. Rev Nutrição

2020;33:e200174.Crossref

27. Smith AC, Thomas E, Snoswell CL, et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: implications for coronavirus disease

2019 (COVID-19). J Telemed Telecare 2020;26:309-13. Crossref

28. Scherrenberg M, Wilhelm M, Hansen D, et al. The future is now: a call for action for cardiac telerehabilitation in

the COVID-19 pandemic from the secondary prevention

and rehabilitation section of the European Association of

Preventive Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2021;28:524-40. Crossref

29. Turolla A, Rossettini G, Viceconti A, Palese A, Geri T.

Musculoskeletal physical therapy during the COVID-19

pandemic: is telerehabilitation the answer? Phys Ther

2020;100:1260-4. Crossref

30. Norman CD, Skinner HA. eHealth literacy: essential skills for consumer health in a networked world. J Med Internet

Res 2006;8:e9. Crossref

31. Jasemian Y. Elderly comfort and compliance to modern telemedicine system at home. 1st International ICST

Workshop on Connectivity, Mobility and Patients’ Comfort.

2008. Available from: https://eudl.eu/doi/10.4108/icst.pervasivehealth2008.2516. Accessed 5 May 2020. Crossref

32. Bujnowska-Fedak MM, Grata-Borkowska U. Use of telemedicine-based care for the aging and elderly:

promises and pitfalls. Smart Homecare Technol Telehealth

2015;3:91-105. Crossref

33. Chesser A, Burke A, Reyes J, Rohrberg T. Navigating the digital divide: a systematic review of eHealth literacy in

underserved populations in the United States. Inform

Health Soc Care 2016;41:1-19. Crossref

34. Chua SE, Cheung V, McAlonan GM, et al. Stress and psychological impact on SARS patients during the

outbreak. Can J Psychiatry 2004;49:385-90. Crossref

35. Mak IW, Chu CM, Pan PC, Yiu MG, Chan VL. Long-term psychiatric morbidities among SARS survivors. Gen Hosp

Psychiatry 2009;31:318-26.Crossref

36. Wang Y, Duan Z, Ma Z, et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems among patients with cancer during COVID-19 pandemic. Transl Psychiatry 2020;10:263. Crossref

37. Newell S, Sanson-Fisher RW, Girgis A, Bonaventura A. How well do medical oncologists’ perceptions reflect

their patients’ reported physical and psychosocial

problems? Data from a survey of five oncologists. Cancer

1998;83:1640-51. Crossref

38. Sakai H, Umeda M, Okuyama H, Nakamura S. Differences in perception of breast cancer treatment between patients,

physicians, and nurses and unmet information needs in

Japan. Support Care Cancer 2020;28:2331-8. Crossref

39. Söllner W, DeVries A, Steixner E, et al. How successful are oncologists in identifying patient distress, perceived

social support, and need for psychosocial counselling? Br J

Cancer 2001;84:179-85. Crossref

40. Catania C, Spitaleri G, Del Signore E, et al. Fears and perception of the impact of COVID-19 on patients with

lung cancer: a mono-institutional survey. Front Oncol

2020;10:584612. Crossref

41. Coronavirus.gov. Hong Kong SAR Government. Together, We Fight the Virus. Available from: https://www.coronavirus.gov.hk/eng/index.html. Accessed 7 Nov 2020.