© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Adult patients in paediatric intensive care units

Karen KY Leung, MB, BS, MRCPCH1; KL Hon, MD, FCCM1; Felix Oberender, MRCPCH, FCICM2; Patrick Ip, MB, BS, FRCPCH3; Joanna YL Tung, MB, BS, MRCPCH4

1 Paediatric Intensive Care Unit, Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Paediatric Intensive Care Unit, Monash Children’s Hospital Melbourne and Department of Paediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Australia

3 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

4 Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr KL Hon (ehon@hotmail.com)

Introduction

With advancement in technology and medical

care, approximately 1 in 10 paediatric patients with

chronic diseases and life-threatening conditions can

now survive into adulthood.1 Paediatricians caring

for critically ill adults in the paediatric intensive

care unit (PICU) should be aware of the potential

challenges that are unique to this group of patients.

We recently admitted to our PICU a patient in his 30s

with chronic renal disease and respiratory failure.

The patient had a complex history of end-stage

renal failure due to crescentic glomerulonephritis,

and previous peritoneal dialysis and cadaveric renal

transplant had been unsuccessful. He had received

subsequent haemodialysis under the care of the

paediatric nephrology unit. He had severe skeletal

deformities and multicentric carpotarsal osteolysis

syndrome likely due to a heterozygous mutation in

the MAFB gene.2 The patient developed respiratory

failure and necessitated admission to the PICU for

stabilisation.

In Hong Kong, many patients with chronic

childhood illnesses receive excellent multidisciplinary

care from territory-wide paediatric services. When

these patients reach adulthood, the transition

to adult services involves multiple stakeholders,

including paediatricians, adult physicians, allied

healthcare professionals, and the patient’s family, all

having to work together in the patient’s best interest.

This transition can involve several challenges. Firstly,

paediatricians and paediatric allied health providers

may be unfamiliar with adult diseases and must

continue the child’s care until they are transitioned

to adult services. Likewise, adult physicians are

often unfamiliar with paediatric conditions with

degenerative sequelae and may be reluctant to take

on the risks in managing these patients. Secondly,

there is a lack of comprehensive healthcare policy

on this subject matter, and this can affect healthcare

resource allocation and budgeting. Thirdly, there

is currently no standard paediatric transitional

programme or educational framework to prepare

patients and their families for transition into the adult healthcare services.3 Lastly, patients and

their families, who have become familiar with the

paediatric approach, might have difficulty adapting

to adult services or even lose confidence in their

medical professionals during the transition period.

Transitional care is widely defined as ‘the

purposeful, planned movement of adolescents and

young adults with chronic physical and medical

conditions from child-centred to adult-oriented

healthcare systems’.4 An effective transition process

can provide appropriate high-quality uninterrupted

medical care services for the patient, and a

communication platform for the main participants

in the patient’s treatment to enhance the patient’s

health, life outcomes, self-management, and

autonomy.4 5 6 7 8 9 In contrast, a premature transition

to adult-oriented therapy may lead to insufficient

preparation, resulting in transition failure, non-adherence

to treatment and poor engagement

with healthcare services subsequently, excess

morbidity, and even mortality.10 11 12 Therefore, a better

management strategy for chronically ill adolescents

is necessary to address the additional needs of

patients in adult life.11 Data on the overall number

of patients involved are scarce; however, registries of

subspecialty populations provide strong evidence to

support the general consensus that transitional care

is a growing challenge.13 14

Transitional care of paediatric patients to

adult care in Hong Kong should be easy to carry

out, as the majority of these patients with chronic

conditions are managed under the public healthcare

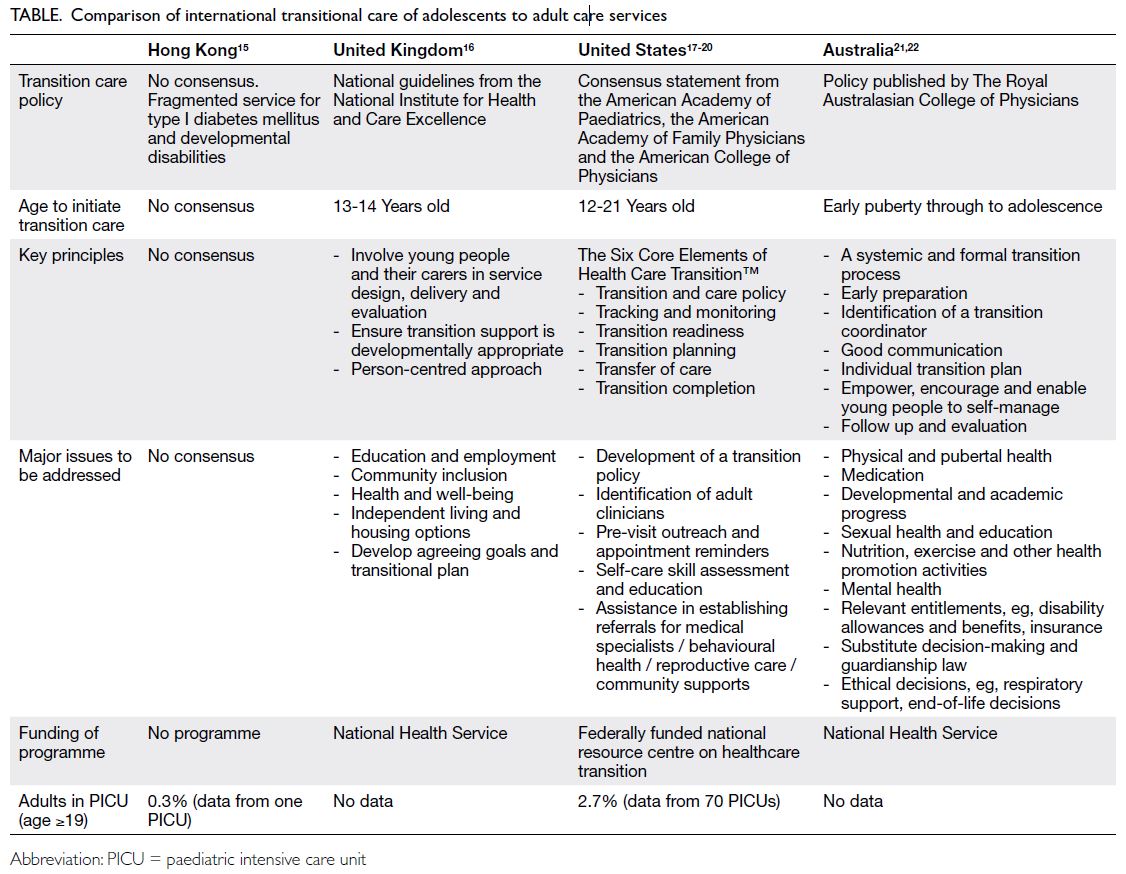

system. However, paediatric transitional care

services in Hong Kong are rather underdeveloped

and fragmented and, in comparison with other

countries, lack an agreed framework3 (Table 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22).

In Hong Kong, only limited success in transition

care has been established, primarily in patients

with cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, and diabetes

mellitus. Notorious challenges are present for those

with oncologic diseases, congenital heart diseases,

chronic renal diseases on renal replacement, and

inborn errors of metabolism. Transitional care for most of these other chronic conditions remains

fragmented, and for solid organ transplant recipients

it is even less developed.8 9 In 2010, a Hong Kong study

reported that it was commonplace for paediatricians

to continue seeing chronically ill adolescents well

into adulthood11; sadly, this remains the case at the

time of writing. In the 2010 study, the majority of

adolescents (85.3%) and parents (82.5%) were willing

to be transferred to adult care; however, fewer than

10% had received any transitional information.11

It is evident that the main obstacle to a successful

transition is the lack of a structured transitional care

programme and healthcare system, not resistance of

patients and families.23

The outcomes of adult PICU patients are

often overlooked in paediatric clinical studies,

and there have been no local data or reports on

adults admitted to a PICU. In a large report of such

patients in the United States, patients aged 21 to 29 years had two-fold greater odds of PICU mortality

compared with adolescent patients, after adjusting

for Paediatric Index of Mortality score, sex, trauma,

and having a complex chronic condition. Being aged

≥30 years was associated with a 3.5-fold greater

odds of mortality.17 It is difficult to draw a general

conclusion on whether a PICU or an adult intensive

care unit can provide the best critical care for this

group of patients. Paediatricians are more familiar

with some childhood-onset chronic conditions than

adult physicians; however, paediatricians may not

have the expertise to optimise the care of adult-acquired

conditions. Therefore, some investigators

have suggested that PICUs should have plans and

protocols specifically focused on this group of adult

patients.17

Transitional care programmes should be

tailored to the specific medical condition to ensure

optimal care and outcomes. Adult congenital heart disease or cystic fibrosis, for example, are obvious

candidates for the establishment of centralised,

disease-specific services that would bring together

specific paediatric and adult expertise for small and

complex patient cohorts.24 25 Other more common

conditions such as cerebral palsy, asthma or type 1

diabetes will benefit from a broader framework that

can guide clinicians and patients through a successful

transition from paediatric to adult care in a variety

of healthcare settings. A successful transitional

programme should include the following factors:

(1) a structured and written policy; (2) patient and

family involvement in preparation and planning;

(3) adequate training for staff and sensitisation to

the needs of adolescent patients; (4) continuity of

care to adult service (eg, paediatricians and adult

physicians should develop and implement joint

recommendations on diagnosis and treatment); and

(5) financial support for special healthcare service

needs.1 In addition to transitional care for chronic

medical conditions, psychiatric disorders, including

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or autism,

should also be addressed. Developing transitional

care programmes for adolescents is an important

healthcare policy, as it can improve adherence

to healthcare services, long-term outcomes for

the patient, and better utilisation of healthcare

resources.12

As survival rates improve for chronic childhood

conditions, it is inevitable that some adults with

rare childhood conditions, especially those with

congenital heart disease, might be admitted

to a PICU. The PICUs should have protocols,

infrastructures, and transition pathways specifically

focusing on this unique group of adults, who are

‘too old’ to be a paediatric patient, but might not be

best treated in an adult intensive care unit.17 From

initiating collaboration with adult physicians to

developing a structured transitional care programme

covering both in-patient and out-patient services,

paediatricians are ultimately responsible for the

clinical care and long-term outcomes of this group

of adult patients, so that they are not overlooked by

our healthcare system. This process should be an

integral practice of humanism, humanistic medicine,

and humanitarianism. The modern PICU may take

on an additional role as a ‘Progressive Integrative

Care Unit’.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design of the study, acquisition of the data, analysis or interpretation of the

data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the

manuscript for important intellectual content.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KL Hon was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts

of interest. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Mazur A, Dembinski L, Schrier L, Hadjipanayis A,

Michaud PA. European Academy of Paediatric consensus

statement on successful transition from paediatric to adult

care for adolescents with chronic conditions. Acta Paediatr

2017;106:1354-7. Crossref

2. Zankl A, Duncan EL, Leo PJ, et al. Multicentric carpotarsal

osteolysis is caused by mutations clustering in the amino-terminal

transcriptional activation domain of MAFB. Am J

Hum Genet 2012;90:494-501. Crossref

3. Lau KK. Transition care in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2016;22:408-9. Crossref

4. Blum RW, Garell D, Hodgman CH, et al. Transition from

child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents

with chronic conditions. A position paper of the Society

for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health 1993;14:570-6. Crossref

5. van Staa AL, Jedeloo S, van Meeteren J, Latour JM. Crossing

the transition chasm: experiences and recommendations

for improving transitional care of young adults, parents

and providers. Child Care Health Dev 2011;37:821-32. Crossref

6. Fair C, Cuttance J, Sharma N, et al. International and

interdisciplinary identification of health care transition

outcomes. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:205-11. Crossref

7. Rosen DS, Blum RW, Britto M, Sawyer SM, Siegel DM,

Society for Adolescent Medicine. Transition to adult

health care for adolescents and young adults with chronic

conditions: position paper of the Society for Adolescent

Medicine. J Adolesc Health 2003;33:309-11. Crossref

8. McDonagh JE, Kelly DA. Transitioning care of the pediatric recipient to adult caregivers. Pediatr Clin North

Am 2003;50:1561-83. Crossref

9. Jin YT, Chen CM, Chien WC. Factors influencing

transitional care from adolescents to young adults with

cancer in Taiwan: a population-based study. BMC Pediatr

2016;16:122. Crossref

10. Reiss J, Gibson R. Health care transition: destinations

unknown. Pediatrics 2002;110:1307-14. Crossref

11. Wong LH, Chan FW, Wong FY, et al. Transition care for

adolescents and families with chronic illnesses. J Adolesc

Health 2010;47:540-6. Crossref

12. Gabriel P, McManus M, Rogers K, White P. Outcome

evidence for structured pediatric to adult health care

transition interventions: a systematic review. J Pediatr

2017;188:263-9.e15. Crossref

13. Bell SC, Mall MA, Gutierrez H, et al. The future of cystic

fibrosis care: a global perspective. Lancet Respir Med

2020;8:65-124. Crossref

14. Iyengar AJ, Winlaw DS, Galati JC, et al. The Australia and

New Zealand Fontan Registry: description and initial

results from the first population-based Fontan registry.

Intern Med J 2014;44:148-55. Crossref

15. Pin TW, Chan WL, Chan CL, et al. Clinical transition for adolescents with developmental disabilities in Hong Kong: a pilot study. Hong Kong Med J 2016;22:445-53. Crossref

16. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, UK

Government. Transition from children’s to adults’ services

for young people using health or social care services. NICE

guideline [NG43]. 2016. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng43. Accessed 27 Aug 2020.

17. Edwards JD, Houtrow AJ, Vasilevskis EE, Dudley RA, Okumura MJ. Multi-institutional profile of adults

admitted to pediatric intensive care units. JAMA Pediatr

2013;167:436-43. Crossref

18. McManus M, White P, Schmidt A, et al. Health care gap affects 20% of United States population: transition

from pediatric to adult health care. Health Policy OPEN

2020;1:100007. Crossref

19. White PH, Cooley WC, Transitions Clinical Report

Authoring Group, American Academy of Pediatrics,

American Academy of Family Physicians, American

College of Physicians. Supporting the health care transition

from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home.

Pediatrics 2018;142:e20182587. Crossref

20. gotransition.org. Overview: transitioning youth to an adult

health care clinician. 2020. Available from: https://www.gottransition.org/6ce/?leaving-full-package. Accessed 27

Aug 2020.

21. The Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Transition

of young people with complex and chronic disability needs

from paediatric to adult health services. 2014. Available from:

https://www.racp.edu.au/docs/default-source/advocacy-library/transition-of-young-people-with-complex-and-chronic-disability-needs.pdf. Accessed 27 Aug 2020.

22. Agency for Clinical Innovation, Australia Government. Key

principles for transition of young people from paediatric

to adult health care. 2014. Available from: https://www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/251696/Key_Principles_for_Transition.pdf. Accessed 27 Aug 2020.

23. Scal P, Evans T, Blozis S, Okinow N, Blum R. Trends in transition from pediatric to adult health care services for

young adults with chronic conditions. J Adolesc Health

1999;24:259-64. Crossref

24. Bassareo PP, Mcmahon CJ, Prendiville T, et al. Planning

transition of care for adolescents affected by congenital

heart disease: the Irish national pathway. Pediatr Cardiol

2022 Jun 23. Epub ahead of print. Crossref

25. Office D, Heeres I. Transition from paediatric to adult care in cystic fibrosis. Breathe (Sheff) 2022;18:210157. Crossref