Hong Kong Med J 2022 Oct;28(5):411-2 | Epub 30 Jun 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

Helping a patient with suicidal ideation: an

ethical perspective

Season HL Ho, BSc Applied Sciences (Health Studies); Ben YF Fong, MPH (Syd), FHKAM (Community Medicine)

Division of Science, Engineering and Health Studies, College of Professional and Continuing Education, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Ms Season HL Ho (hiulamseasonho@gmail.com)

“To be or not to be” is a well-known monologue from Shakespeare’s play Hamlet. The monologue

reflects the internal mental conflicts that many

people face in complex situations. Although we

are not all protagonists of a play, everyone faces

plenty of ethical dilemmas in their daily life. Ethical

dilemma occurs when a moral problem involving

two or more mutually exclusive, morally correct

actions.1 Indeed, healthcare practitioners also face

plenty of ethical dilemmas in practice. It is crucial

for healthcare practitioners to have a mindset that

is legal, ethical, and socially responsible,2 because

their decisions influence the outcome. Very often

healthcare practitioners and patients have different

perspectives of views on the same issue. Bioethics

is a set of moral principles that practitioners should

follow, but these principles can conflict with patient

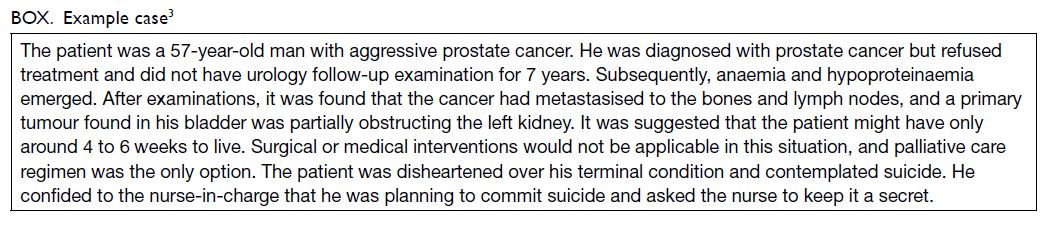

autonomy. An example case3 has been selected from

the literature because it provides an example of a

common encounter of ethical dilemma in clinical

practice (Box).

Autonomy or beneficence

The patient in this example (Mr X) unintentionally

placed the nurse in an ethical dilemma. When Mr

X disclosed the suicidal ideation (SI), the nurse had

two morally correct choices: conceal the truth or

report the SI. Concealing the truth would respect the

patient’s autonomy; however, this violates the code

of ethics for nurses. Reporting the SI to members

of the team not providing direct care to the patient

would comply with the beneficence principle, or

‘duty to warn’. This principle is an obligation for

healthcare practitioners to warn the potential victim if a patient reports an intention to cause imminent

danger or harm. However, reporting the SI would

violate the patient’s autonomy and breach patient

confidentiality, and this is particularly so in the

Hong Kong setting. The dichotomy between patient

autonomy and beneficence leads to a dilemma.

Neither can be chosen without violating the other.

Autonomy refers to the right of the patient

to make independent decisions for their care.

Healthcare professionals should respect patient

decisions without influencing or interrupting.4

Beneficence is the obligation of healthcare

professionals to act for the benefit of the patient

and to remove conditions that cause harm,5 and to

enhance patient health and well-being. In addition

to these two principles, non-maleficence should also

be considered. Non-maleficence is the obligation

of healthcare professionals to ‘do no harm’ to the

patient through negligence.6

It is a sophisticated decision to choose between

autonomy and the beneficence. Placing a priority on

identifying whether Mr X had the ability to make

an appropriate decision was required. Patients

with cancer are more likely to have very strong

psychological reactions, including suicide attempts7

or making “irresponsible” decisions that induce

severe consequences. In this situation, healthcare

professionals must override patient autonomy.8

Mental assessment and physical examination can

identify whether the patient can make informed

and appropriate decisions. If mental disorders

or unstable emotional conditions are diagnosed,

practitioners must guide them back to the right track

by good clinical practice and offer coordinated care.

To avoid unnecessary harm, the nurse should pick beneficence and non-maleficence in this situation.

Choosing to conceal the secret would satisfy

Mr X but could lead to traumatic consequences for

Mr X’s family and potentially even the healthcare

providers involved. Choosing to tell the truth would

satisfy his family and healthcare providers. The

family members could spend more time with Mr X,

and the healthcare providers could fulfil their duty.

Therefore, reporting the secret is considered the

more ethical choice, despite going against the wishes

of the patient.

Evaluation and treatment of

patients with suicidal ideation

Some patients with terminal illnesses have the desire for hastened death, and some request assisted suicide

or exhibit signs of suicidal ideation (SI).9 Suicidal

ideation is correlated with psychiatric disorders

that adversely affect the patient’s emotional and

psychological behaviour.10 Patients with cancer have

higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders.11 Despite

the high prevalence, <50% of cancer patients with

psychiatric disorders are identified and assigned

the appropriate care.11 Thus, it was fortunate that

Mr X was willing to express SI to the nurse. Symptom

assessments and psychological care in palliative care

are warranted. The patient’s psychiatric symptoms or

stressors should be identified before they manifest.

Patients with end-of-life illnesses often

experience severe pain and anxiety, leading to

psychological distress. However, psychological

support is insufficient in most cases. Under the

intense working environment in the medical ward,

medical practitioners often focus more on clinical

treatments rather than supportive care such as

recognising the patient’s needs and relieving the

anxiety of the patient and their family. Furthermore,

management and training in palliative care and end-of-life care are often neglected in medical education,12

and this remains the case in Hong Kong. Psychiatric

symptoms or even SI are often overlooked.

There are noticeable differences between

common clinical care and palliative care, which

is more holistic. In addition to the traditional

components of clinical assessment, palliative

care includes four unique domains: physical,

psychological, social and family, and spiritual.

Clinical knowledge and skills are the focus of medical

training programmes, but the beliefs and values that

underpin professional medical practice are seldom

addressed. Owing to societal norms in Hong Kong,

patients are reluctant to discuss the topic of “dying”

openly with their physicians. Gaps are found in

medical assessment in palliative care patients.13 To

alleviate the issue, more training in palliative care,

end-of-life issues, and ethical principles, should be

included in the curriculum for medical training.

Palliative care is patient- and family-centred care.14 Families and family caregivers can play a significant role in providing support

and encouragement. This can help the patients

to redefine themselves, and eventually improve

their physical status and intrapersonal features.

Furthermore, patients are more willing to talk with

family members instead of practitioners, improving

the possibility of identifying any abnormalities in the

patient’s mental and physical condition.

Conclusion

Practitioners’ decisions and actions affect patients’ lives and care. It is important for practitioners to assess which action is most appropriate for

the situation, even where there are two or more

morally correct approaches. Practitioners must be

responsible for the choices they make, and should

refer the patient to relevant services to support their

decisions. They should refer to and analyse the code

of ethics and related literature before making ethical

decisions.

Author contributions

Concept or design: Both authors.

Acquisition of data: SHL Ho.

Analysis or interpretation of data: Both authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: SHL Ho.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Both authors.

Acquisition of data: SHL Ho.

Analysis or interpretation of data: Both authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: SHL Ho.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Both authors.

Both authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

Both authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Chandra S, Mohammadnezhad M, Ward P. Trust and communication in a doctor- patient relationship: a

literature review. J Healthc Commun 2018;3:36. Crossref

2. Mujtaba BG, Cavico FJ, Nonet G, Rimanoczy I, Samuel M. Developing a legal, ethical, and socially responsible mindset for business leadership. Adv Soc Sci Res J 2015;2:9-26. Crossref

3. Jie L. The patient suicide attempt—an ethical dilemma case study. Int J Nurs Sci 2015;2:408-13. Crossref

4. Varkey B. Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Med Princ Pract 2021;30:17-28. Crossref

5. Pandit MS, Pandit S. Medical negligence: coverage of the profession, duties, ethics, case law, and enlightened defense—a legal perspective. Indian J Urol 2009;25:372-8. Crossref

6. Southern New Hampshire University. Why ethics in

nursing matters. Available from: https://www.snhu.edu/about-us/newsroom/2018/05/ethics-in-nursing. Accessed 21 Sep 2021.

7. Howard OM, Fairclough DL, Daniels ER, Emanuel EJ. Physician desire for euthanasia and assisted suicide:

would physicians practice what they preach? J Clin Oncol

1997;15:428-32. Crossref

8. Loewy EH. Beneficence in trust. Hastings Cent Rep 1989;19:42-3. Crossref

9. Goelitz A. Suicidal ideation at end-of-life: the palliative care team’s role. Palliat Support Care 2003;1:275-8. Crossref

10. Salters-Pedneault K. Types of psychiatric disorders.

Available from: https://www.verywellmind.com/psychiatric-disorder-definition-425317. Accessed 21 Sep

2021.

11. Rivest J, Levenson J. Clinical features and diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in patients with cancer: overview. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-psychiatric-disorders-in-patients-with-cancer-overview. Accessed 21 Sep 2021.

12. Woo JA, Maytal G, Stern TA. Clinical challenges to the delivery of end-of-life care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2006;8:367-72.

13. Lam WM. Palliative care in Hong Kong—past, present and future. HK Pract 2019;41:39-46.

14. Steele R, Davies B. Supporting families in palliative

care. Oxford Medicine Online. Available from:

https://oxfordmedicine.com/view/10.1093/med/9780190244132.001.0001/med-9780190244132-chapter-3. Accessed 21 Sep 2021.