Hong Kong Med J 2022 Oct;28(5):376-82 | Epub 13 Sep 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Vaginal delivery of second twins: factors predictive of failure and adverse perinatal outcomes

SL Mok, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology); TK Lo, MB, BS, FHKAM (Obstetrics and Gynaecology)

Department Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr SL Mok (juliaslmok@yahoo.com.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: This study was performed to explore

factors associated with adverse perinatal outcomes

for second twins and to identify predictive factors

for successful vaginal delivery of the second twin

after vaginal delivery of the first twin.

Methods: This 10-year retrospective study included

231 cases of twin pregnancies in which vaginal

delivery of the second twin was attempted after

vaginal delivery of the first twin. The relationships of

obstetric characteristics with the composite adverse

perinatal outcome of the second twin were analysed.

Predictive factors for successful vaginal delivery of

the second twin were also explored.

Results: Gestational age <32 weeks was the only

independent risk factor for the composite adverse

perinatal outcome and neonatal intensive care

unit admission for the second twin. A longer inter-twin

delivery interval was associated with greater

risk of caesarean delivery of the second twin, but

it did not increase the risk of an adverse perinatal

outcome. Non-vertex presentation of the second twin at delivery was independently associated with

caesarean delivery (9.0% vs 2.0%, P=0.03). For second

twins in breech presentation, caesarean delivery was

associated with the presence of less experienced

birth attendants.

Conclusion: Among second twins born to mothers

who had attempted vaginal delivery, adverse perinatal

outcomes were mainly related to prematurity. The

presence of more experienced birth attendants

may contribute to successful vaginal delivery of the

second twin, particularly for twins in non-vertex

presentation.

New knowledge added by this study

- Among second twins born to mothers who had attempted vaginal delivery, adverse perinatal outcomes were mainly related to prematurity, rather than actual mode of delivery.

- An inter-twin delivery interval of >30 minutes alone did not increase the risk of an adverse perinatal outcome, although it increased the risk of caesarean delivery of the second twin.

- For second twins in breech presentation, caesarean delivery was independently associated with a longer intertwin delivery interval (>30 minutes) and the presence of less experienced birth attendants.

- Our findings support vaginal delivery of the second twin when the first twin is delivered in cephalic presentation.

- If monitoring of the second twin is possible and the findings are reassuring, obstetricians may consider a conservative approach, even 30 minutes after delivery of the first twin; emergency caesarean delivery should be readily available if necessary.

Introduction

Selection of the mode of delivery in a twin pregnancy

is always challenging for obstetricians, although

vaginal delivery is theoretically feasible for diamniotic

twins if the first twin is in cephalic presentation.1

In the past 15 years, two cohort studies2 3 and a

multicentre randomised trial4 concluded that when

the first twin was in cephalic presentation, planned

caesarean delivery did not significantly decrease or

increase the risk of fetal/neonatal death or serious

neonatal morbidity, compared with planned vaginal delivery. These findings suggest that vaginal delivery

of twins is a safe and reasonable mode of delivery.

However, attempts to deliver vaginally are not always

successful, and the intrapartum risks of adverse

outcomes for second twins should be carefully

considered.

In a study of factors that were predictive of

successful vaginal delivery, Easter et al5 found that

the vaginal delivery rates of second twins in non-vertex

presentation were comparable with the vaginal

delivery rates of second twins in vertex presentation. Successful vaginal delivery was associated with

higher parity. In the subgroup of second twins in non-vertex

presentation, successful vaginal delivery was

associated with the presence of more experienced

birth attendants. The rates of neonatal morbidity

and mortality were low in both groups, and they did

not differ between groups. However, that study only

included twins with gestational ages of ≥32 weeks.

In a study that examined caesarean delivery

of the second twin after successful vaginal delivery

of the first twin, Breathnach et al6 found that the

most common indication for caesarean delivery of

the second twin was malpresentation (transverse/shoulder/brow) or compound presentation. Second

twins who were delivered by emergency caesarean

section after vaginal delivery of the first twin had a

perinatal morbidity rate of 29%, but there were only

14 such twins; thus, the sample size was insufficient

for robust statistical analysis.

There is a need for additional information

concerning factors predictive of successful vaginal

delivery of the second twin, which will allow

better case selection and avoid combined vaginal-caesarean

delivery (ie, failed vaginal delivery of the

second twin). To our knowledge, there have been few

studies of these factors in Asian populations. Here,

we examined the medical records of second twins

born to mothers who had attempted vaginal delivery

of twins in Hong Kong; we sought to identify factors

that could affect the perinatal outcomes and predict

failure of vaginal delivery in a predominantly Asian

population. We also included deliveries of preterm

gestations (23-32 weeks), which were not extensively

investigated in previous studies.

Methods

This retrospective study focused on twin pregnancies

that were delivered between 1 January 2006 and 31

December 2015 in Princess Margaret Hospital, a

regional public hospital in Kowloon, Hong Kong.

Inclusion criteria were vaginal delivery of the first

twin at gestational viability or beyond. Exclusion

criteria were miscarriage (delivery before gestational

viability) or delivery of the first twin by elective

or emergency caesarean section. Under Hong

Kong law, 24 full weeks of gestation is generally

regarded as the threshold of gestational viability. In

exceptional cases, the threshold may be reduced to

23 weeks if, after full discussion with the obstetric

and neonatal care teams, the parents demonstrate

a strong preference for earlier initiation of active

neonatal management.

Eligible cases were identified from the Obstetric Clinical Information System (OBSCIS); for each case,

the mother’s demographic and clinical data were

retrieved. The OBSCIS is a territory-wide electronic

database that contains the prenatal, intrapartum, and

postpartum information of all mothers who receive

care in public hospitals in Hong Kong. Clinical

information in the system is updated in a timely

manner by each patient’s midwives and physicians

before the patient is discharged from the hospital.

Data entry integrity is continuously monitored by

a dedicated information technology team within

the Hospital Authority, and each obstetrics unit

is asked to provide missing data promptly. Each

infant’s clinical information was retrieved from the

Electronic Patient Record, a comprehensive system

that contains all health information (except obstetric

records) of patients from birth to death and is shared

by all public hospitals and out-patient clinics under

the Hong Kong Hospital Authority.

The following maternal data were retrieved:

age, parity, gestational age at delivery, chorionicity,

and mode of delivery of the second twin. The

following infant data were retrieved: birth weight,

Apgar score, cord blood pH, delivery time, inter-twin

delivery interval, presentation at delivery, and

neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission

status.

The primary outcome of the study was

a composite adverse perinatal outcome that

included any of the following: Apgar score <6 at

5 minutes after birth, cord blood pH <7, NICU

admission, birth trauma, and presence of neonatal

complications. For infants with a hospital stay of

>28 days, complications until hospital discharge

were included. The following complications were

considered: respiratory morbidity, intracranial

haemorrhage, hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy,

sepsis, metabolic disturbance, birth defects, and

neonatal death. The secondary outcome was mode

of delivery. Gestational age was established by the patient’s last menstrual period and verified by

ultrasound in the first or early second trimester.

Chorionicity was established by prenatal ultrasound

and confirmed by placental histology after delivery.

The likelihood of vaginal delivery may be adversely

impacted by considerably larger second twin size,

compared with the first twin. Breathnach et al6

found that the rate of caesarean section was higher

if the first twin had ≥20% lower weight than the

second twin. Therefore, clinically significant weight

discordance was regarded as ≥20% in the present

study, where weight discordance was defined as the

weight difference between the second and first twin

divided by the weight of first twin.

Vaginal deliveries of twins were managed in

accordance with our labour ward protocol, which

does not regard estimated fetal weight discordance as

a contra-indication to vaginal delivery. All deliveries

were attended by two physicians (as described

below) and assisted by ≥2 midwives. Specialist

supervision was recommended. In this context,

a specialist is an obstetrician who has completed

≥6 years of postgraduate residency training and

received accreditation as a Fellow of the Hong

Kong College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

(FHKCOG). Membership in the Royal College of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (MRCOG) is a

prerequisite for FHKCOG accreditation. When a

specialist was unavailable (particularly at night),

deliveries were conducted or supervised by an

MRCOG-qualified physician. Paediatricians were

present for all deliveries of second twins. Prenatal

steroids (either betamethasone or dexamethasone

depending on pharmacy availability and initial

treatment at the referral unit) were administered

in cases of delivery before 34 weeks of gestation.

If necessary, oral nifedipine was used as a first-line

tocolytic. Intravenous salbutamol was used as a

second-line tocolytic until 2012; since 2013, atosiban

has been used as a second-line tocolytic.

Statistical analysis was carried out using

SPSS software (Windows version 17.0; SPSS Inc.,

Chicago [IL], United States). Categorical data were

analysed by the Chi squared test or Fisher’s exact

test, as appropriate. Among the factors that showed

statistical significance in univariate analysis, binary

logistic regression was used to identify factors that

were independently predictive of vaginal delivery

and adverse perinatal outcomes. P values <0.05 were

considered statistically significant.

Results

During the 10-year study period, 47 595 deliveries

were performed in Princess Margaret Hospital;

718 twin pairs were delivered. Among these twin

pairs, 182 and 305 were delivered by elective and

emergency caesarean section, respectively; they were excluded from the study. In the remaining

231 cases, the mothers delivered the first twin

vaginally and intended to deliver the second twin

vaginally. The second twins in this group of patients

were included for analysis.

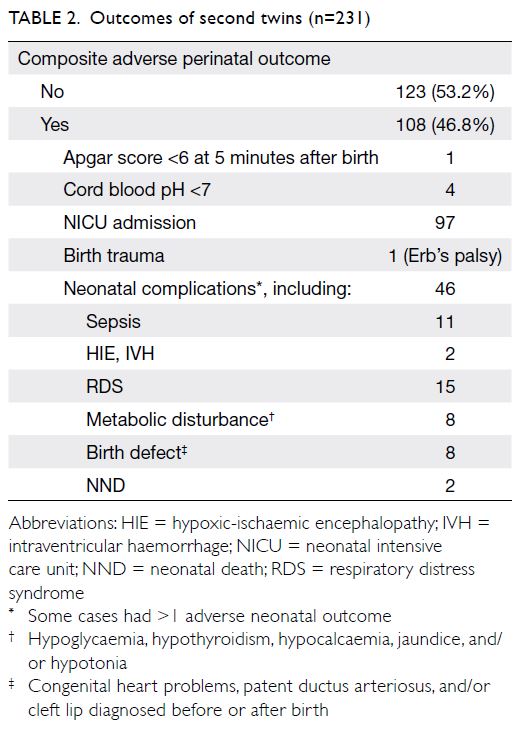

Table 1 shows the demographic and obstetric

characteristics of the 231 cases, stratified according

to the mode of delivery of the second twin.

Emergency caesarean delivery was required in

10 cases (4.3%). Among the three second twins in

vertex presentation, two were delivered by caesarean

section because of second twin retention; the

remaining twin was delivered by caesarean section

because of fetal distress. Among the seven second

twins in non-vertex presentation, the indications for

caesarean delivery were second twin retention (two

cases), fetal distress (four cases), and transverse lie

(one case). Of the factors shown in Table 1, only an

inter-twin delivery interval of >30 minutes and non-vertex

presentation of the second twin at delivery

were associated with the mode of delivery of the

second twin. Logistic regression analysis showed

that an inter-twin delivery interval of >30 minutes

(odds ratio [OR]=26.952, 95% confidence interval

[CI]=5.924-122.619) and non-vertex presentation

of the second twin at delivery (OR=5.003,

95% CI=1.101-22.743) were independently

associated with caesarean delivery of the second

twin.

Table 1. Demographic and obstetric characteristics of 231 cases of twin pregnancies in which vaginal delivery of the second twin was attempted after vaginal delivery of the first twin

In subgroup analyses, we examined the

relationships of the demographic and obstetric

factors in Table 1 to determine their relationships

with the mode of delivery for second twins in breech

presentation. Univariate analysis revealed that only

an inter-twin delivery interval >30 minutes and

the presence of less experienced birth attendants

were significantly associated with the mode of

delivery. Logistic regression showed that an inter-twin

delivery interval >30 minutes (OR=36.492,

95% CI=3.035-438.712) and the presence of

less experienced birth attendants (OR=10.252,

95% CI=1.001-104.956) were independently

associated with caesarean delivery of second twins

in breech presentation.

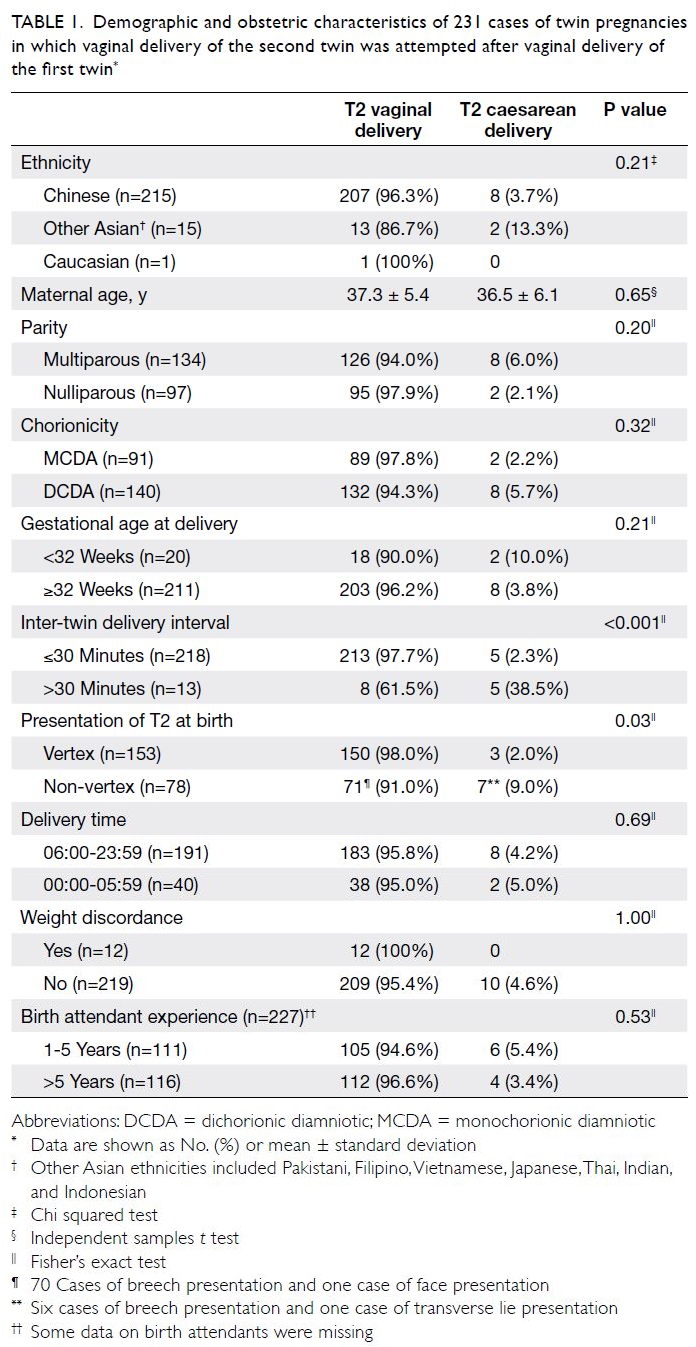

Perinatal outcomes of second twins are

shown in Table 2. Univariate analysis revealed

that the composite adverse perinatal outcome was

only associated with gestational age <32 weeks

(P<0.001; OR=12.1, 95% CI=2.738-53.481) [Table 3].

Similarly, gestational age <32 weeks was the only

factor significantly associated with NICU admission

(P<0.001; OR=6.420, 95% CI=2.073-19.878) [Table 4].

Among the 47 cases with delivery before 34

weeks of gestation, 27 completed steroid treatment

before delivery. In 17 cases, delivery occurred before

the completion of steroid treatment because of rapid

labour that did not respond to tocolytics. Steroid

treatment was not administered in three cases; two of these cases involved delivery before 24 weeks

of gestation, which is the threshold for beginning

steroid treatment in our hospital. In the third

case, the mother was admitted in advanced labour.

Completion or non-completion of steroid treatment

was not associated with the composite adverse

perinatal outcome (25/27 vs 18/20, P=0.753).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study in Hong Kong concerning the short-term composite adverse

perinatal outcomes of second twins in cases where

vaginal delivery was attempted. Our approach

enabled simultaneous consideration of multiple

outcome parameters. The inclusion of additional

clinical information until hospital discharge for

infants with prolonged hospital stay (>28 days)

allowed a more comprehensive assessment of

outcomes. Notably, cases of gestation <32 weeks

were included; there are minimal published data

for this group of infants because they have been

excluded from many large trials. Additionally, we

examined the effects of birth attendant experience

and birth timing.

Perinatal outcomes

Prior to this study, there were two analyses of twin deliveries in a predominantly Asia population,

both from Hong Kong. The first analysis mainly

focused on patient preference regarding the mode

of delivery; it also included few vaginal deliveries

(35 cases).7 The second analysis, reported by Tang

et al,8 was performed in the same obstetric unit

as the first analysis; it reviewed neonatal and

maternal outcomes after an increase in the rate of

vaginal delivery of twins. The authors did not find any significant differences in neonatal morbidities

between the vaginal delivery group and the elective

caesarean delivery group. However, there were fewer

successful vaginal deliveries of ≥1 twin (72 cases)

and the effect of inter-twin delivery interval was not

evaluated.

In this study, the main factor that affected

the composite adverse perinatal outcome was

gestational age; complications were mainly related

to prematurity. Similarly, NICU admission was

mainly related to complications of prematurity,

rather than complications of vaginal delivery. There

were no statistically significant differences in adverse

perinatal outcomes, even for twins who were not

delivered in cephalic presentation. Thus, non-cephalic

presentation alone should not be considered

sufficient to recommend caesarean delivery for twin

pregnancies.

A study in Hong Kong by Leung et al,9 published

in 2002, showed that all umbilical cord blood gas

parameters in the second twin were significantly

associated with the inter-twin delivery interval. The

risk of severe fetal acidosis was 27% if the second twin

was not delivered ≤30 minutes after delivery of the

first twin, but the outcomes of second twins were not

analysed. In our study, an inter-twin delivery interval

of >30 minutes alone did not increase the risk of

short-term adverse perinatal outcomes, although it

increased the risk of caesarean delivery of the second

twin. Schneuber et al10 also reported similar findings

in their series, which suggested that an increased

inter-twin delivery interval was not associated with

adverse fetal outcomes. If monitoring of the second

twin is possible and the findings are reassuring,

obstetricians may thus consider a conservative

approach, even 30 minutes after delivery of the first

twin; however, emergency caesarean delivery should

be readily available if necessary.

Our study also showed no increase in adverse

perinatal outcomes for infants who were delivered

after midnight. In general, delivery of twins in

daytime or early evening is preferable because

additional staff are present, and those staff are often

more experienced. Therefore, when there are no

indications for urgent delivery, the usual practice

in our unit is to begin labour induction for twin

pregnancies in the early morning. Deliveries after

midnight usually follow spontaneous labour and

are thus unplanned. However, such deliveries are

supervised by the most senior on-call obstetrician

(MRCOG-qualified or FHKCOG-accredited) during

the intrapartum period.

Delivery of non-cephalic second twin

The vaginal delivery of second twins in non-cephalic presentation is challenging. Our findings showed

a higher rate of caesarean delivery for second

twins in non-cephalic presentation (9.0% vs 2.0%, P=0.03). In a large cohort study using the World

Health Organization Global Survey dataset, Vogel

et al11 showed that caesarean rates were 6.2% and

0.9% for second twins in non-cephalic and cephalic

presentation, respectively. Another study by Kong

et al12 revealed the caesarean delivery rates of

second twins were 4.7% in cephalic presentation,

11.1% in breech presentation, and up to 90% in

transverse lie. In both of these studies, analyses were

conducted based on the presentation of the second

twin at the onset of labour; their findings were

consistent with our results. The presence of more

experienced obstetricians who are able to perform

artful manoeuvres (ie, internal podalic version and

external cephalic version) can increase the likelihood of successful vaginal delivery of the second twin.

Regular training and rehearsal of the vaginal delivery

of twins is important for obstetricians to maintain

their skills.

Caesarean section of second twin

In our study, caesarean delivery of the second twin

was necessary in 4.3% of cases, which is similar to

or lower than the proportions in other series.6 8 13 14

Regardless of whether the second twin was delivered

by caesarean section, there were no significant

increases in short-term adverse perinatal outcomes;

however, this mode of delivery is less favourable for

mothers. These results are contrary to the findings by

Breathnach et al,6 in which the perinatal morbidity

rate was 29% among second twins delivered by

emergency caesarean section after vaginal delivery

of the first twin. A systematic review by Rossi et al15

also showed a higher rate of morbidity in second

twins after caesarean delivery (19.8% vs 9.5% after

vaginal delivery). Thus, combined vaginal-caesarean delivery of twins should be avoided whenever possible.

In the present study, the presence of a larger

second twin (≥20% weight discordance) did not

significantly increase the risk of caesarean delivery.

The second twin was larger in only 12 cases (5.2%).

We suspect that many other cases with a larger second

twin were scheduled for caesarean delivery without

a trial of vaginal delivery. Decisions concerning the

mode of delivery are affected by the estimated fetal

weight, fetal presentation, and whether the mother

has a history of successful vaginal delivery. Various

factors must be carefully considered in each case.

Limitations

There were some limitations in this study. First, the retrospective design may have resulted in missing

data or incomplete data collection. This is not a large

problem because clinical information in the OBSCIS

and the Electronic Patient Record is required to be

updated when each patient is discharged from the

hospital; therefore, these systems are reliable sources

of patient data. Nevertheless, some information

was not retrievable, such as the presentation of

the second twin at the time of first twin delivery

and whether birth attendant manoeuvres were

necessary to deliver the second twin. Second, the

non-randomised analysis might have led to selection

bias concerning the mode of delivery, such that

low-risk cases were over-represented in the study.

The number of second twins delivered by caesarean

section was small; a larger trial is needed to more

comprehensively evaluate such cases.

Conclusion

Among second twins born to mothers who

had attempted vaginal delivery, we found that

adverse perinatal outcomes were mainly related to

prematurity, rather than actual mode of delivery. For

all second twins, an inter-twin delivery interval <30

minutes was associated with a higher rate of vaginal

delivery; for second twins in breech presentation, the

presence of more experienced birth attendants was

also associated with a higher rate of vaginal delivery.

Overall, the risk of caesarean delivery of the second

twin was low. Our findings in a predominantly Asian

population in Hong Kong support vaginal delivery

of the second twin when the first twin is delivered in

cephalic presentation.

Author contributions

This study was planned and designed by both authors. Both authors also jointly performed the data analysis. TK Lo

provided leadership and supervision, while SL Mok wrote

and managed the manuscript. Both authors had full access to

the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version

for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and

integrity.

Conflicts of interest

Both authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee (Ref KW/EX-17-154 (118-02)).

The requirement for patient informed consent was waived

because this was a retrospective review of medical records

that did not involve patient participation.

References

1. Monson M, Silver RM. Multifetal gestation: mode of delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2015;58:690-702. Crossref

2. Peaceman AM, Kuo L, Feinglass J. Infant morbidity and mortality associated with vaginal delivery in twin

gestations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:462.e1-6. Crossref

3. Fox NS, Silverstein M, Bender S, Klauser CK, Saltzman DH,

Rebarber A. Active second-stage management in twin

pregnancies undergoing planned vaginal delivery in a U.S.

population. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:229-33. Crossref

4. Barrett JF, Hannah ME, Hutton EK, et al. A randomized

trial of planned cesarean or vaginal delivery for twin

pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1295-305.Crossref

5. Easter SR, Lieberman E, Carusi D. Fetal presentation and successful twin vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214:116.e1-10.Crossref

6. Breathnach FM, McAuliffe FM, Geary M, et al. Prediction

of safe and successful vaginal twin birth. Am J Obsetet

Gynecol 2011;205:237.e1-7. Crossref

7. Liu AL, Yung WK, Yeung HN, et al. Factors influencing

the mode of delivery and associated pregnancy outcomes

for twins: a retrospective cohort study in a public hospital.

Hong Kong Med J 2012:18:99-107.

8. Tang HT, Liu AL, Chan SY, et al. Twin pregnancy

outcomes after increasing the rate of vagina twin

delivery: retrospective cohort study in a Hong Kong

regional obstetrics unit. J Maternal Fetal Neonatal Med

2016;29:1094-100. Crossref

9. Leung TY, Tam WH, Leung TN, Lok IH, Lau TK. Effect of

twin-to-twin delivery interval on umbilical cord blood gas

in the second twins. BJOG 2002;109:63-7. Crossref

10. Schneuber S, Magnet E, Haas J, et al. Twin-to-twin delivery

time: neonatal outcome of second twin. Twin Res Hum

Genet 2011;14:573-9. Crossref

11. Vogel JP, Holloway E, Cuesta C, Carroli G, Souza JP,

Barrett J. Outcomes of non-vertex second twins, following

vertex vaginal delivery of first twin: a secondary analysis of

the WHO Global Survey on maternal and perinatal health.

BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:55. Crossref

12. Kong CW, To WW. The predicting factors and outcomes

of caesarean section of the second twin. J Obstet Gynaecol

2017;37:709-13. Crossref

13. Yang Q, Wen SW, Chen Y, Krewski D, Fung KF, Walker M.

Neonatal death and morbidity in vertex-nonvertex second

twins according to mode of deliverya and birth weight. Am

J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192:840-7. Crossref

14. Persad VL, Baskett TF, O’Connell CM, Scott HM.

Combined vaginal-cesarean delivery of twin pregnancies.

Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:1032-7. Crossref

15. Rossi AC, Mullin PM, Chmait RH. Neonatal outcomes

of twins according to birth order, presentation and mode

of delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG

2011;118:523-32. Crossref