Hong Kong Med J 2022 Oct;28(5):367-75 | Epub 1 Aug 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Behavioural adaptations and responses to

obstetric care among pregnant women during an early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional survey

PW Hui, MD, FRCOG; Mimi TY Seto, MB, BS, MRCOG; KW Cheung, MB, BS, MRCOG

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr PW Hui (apwhui@hku.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: This study evaluated behavioural

adaptations and responses to obstetric care among

pregnant women during an early stage of the

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Methods: This cross-sectional survey included

pregnant women who received obstetric care from

27 May 2020 to 16 June 2020 in a university-affiliated

hospital in Hong Kong. Responses were collected

with respect to obstetric appointment scheduling,

workplace changes, mask-wearing practices, travel

and quarantine experiences, obstetric service

adjustments, and visiting arrangements. Regression

analysis was used to compare the effects of patient

characteristics on their responses.

Results: In total, 1000 surveys were distributed;

733 pregnant women provided complete survey

responses. Among obstetric-related appointments in

public hospitals, 16% were postponed or cancelled by

pregnant women; such changes were most frequent

among women beyond 24 weeks of gestation,

women who had previous deliveries, and women

who had a history of mental illness. The practice of

working from home imposed psychological stress

and negatively impacted the pregnancy experience in 4.5% of women. Childbirth companionship was

regarded as an important service by 88.1% of women;

only 4.2% agreed with its suspension. Obstetric

service adjustments had the greatest impact on

Chinese women and nulliparous women.

Conclusions: The findings provide an overview

of how pregnant women adapted during an early

stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Women adjusted

obstetric service attendance, began working from

home, and wore masks. Women’s expectations did

not match changes in childbirth companionship and

peripartum services. Hospital administrators should

consider psychological impacts on pregnant women

when implementing service adjustments.

New knowledge added by this study

- Pregnant women, especially women who had previous deliveries and a history of mental illness, were more likely to postpone or cancel obstetric appointments during an early stage of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

- While working from home improved the overall pregnancy experience for most women, it caused psychological stress and had a negative influence in 4.5% of respondents.

- Childbirth companionship was considered important by 88.1% of the respondents; only 4.2% of respondents fully accepted its suspension.

- Obstetricians and policy makers should be aware of mismatches in the expectations of pregnant women concerning childbirth companionship and peripartum services; infection control should be balanced with peripartum needs.

- Obstetric service adjustments had the greatest impact on Chinese women and nulliparous women.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has had

substantial psychosocial impacts worldwide

and caused major behavioural changes. In 2020,

increased stress and anxiety levels were reported in

countries with major disease spread.1 2 3 4 5 6 Pregnancy is considered a risk factor for COVID-19 because

of relative maternal immunosuppression; there is

also a risk of vertical transmission.7 8 9 10 11 Importantly, behavioural changes have been recognised among

pregnant women.4 The pandemic situation could potentially disrupt obstetric care for pregnant women.8 Thus, it is important to study how the pandemic has affected obstetric care and pregnancy experiences.

Considering the severe adult respiratory

syndrome (SARS) outbreaks in 2002 to 2003 in

Hong Kong, a serious alert level was announced

on 4 January 2020 in response to the emergence of

novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China.12 13

This was escalated to an emergency alert level on

25 January 2020. Corresponding policies were

imposed in public hospitals with each alert

announcement. In obstetric units, husbands and

partners were no longer allowed to accompany

pregnant women for labour and delivery. No visiting

was allowed for mothers or babies staying with their

mothers in postnatal wards. All antenatal exercise

classes, antenatal seminars, hospital tours, and

postnatal classes were suspended. Many workplaces

for women and their partners shifted to working from

home. These changes were coupled with suspensions

of schools and non-urgent community services.

The infection continued to spread worldwide;

the COVID-19 pandemic was recognised by the

World Health Organization on 11 March 2020.

On 20 March 2020, the first case of COVID-19 in

a pregnant woman was confirmed in Hong Kong.

The local government subsequently restricted travel

with additional quarantine measures and mandated

social distancing in late March 2020.12 This study

was conducted in the middle of 2020 to examine how

pregnant women responded to changes in obstetric

care and alterations in the workplace during an early

stage of the COVID-19 pandemic; it also investigated their adaptations to the practices of mask wearing

and social distancing.

Methods

This prospective questionnaire survey was conducted in the obstetric unit of a university-affiliated tertiary

public hospital in Hong Kong from 27 May 2020

to 16 June 2020 in English (online supplementary Table 1) and Traditional Chinese (online supplementary Table 2). Pregnant women were

invited to participate in an online questionnaire

upon admission to obstetric wards or attendance

to obstetric clinics; each invitation was provided

by a midwife (in an obstetric ward) or a designated

research assistant (in an obstetric clinic). Clinic

sessions included an antenatal check-up, ultrasound

scan, and screenings for gestational diabetes and

Group B streptococcus. The survey was administered

to all women who could read either Chinese or

English. Each woman received an information

leaflet containing an introduction of the project, a

description of key events related to COVID-19 from

January 2020 to March 2020, and a QR code linked

to an online survey. The participants could begin

the survey by scanning the QR code, selecting the

language, and providing their consent.

The survey was developed by the authors and

tailored to address issues related to the impacts

of COVID-19 on obstetric services. Prior to this

study, the survey content was validated by local

consultant obstetricians and midwives; it consisted

of demographic data collection and questions that

involved five domains. These domains were related

to obstetric appointment scheduling, workplace

changes, mask-wearing practices, travel and

quarantine experiences, and adjustments to birth

companionship and visiting hours since the first

novel coronavirus alerts were announced in January

2020. Concerning obstetric appointment scheduling,

participants were asked whether their appointments

had been postponed or rescheduled from a public

hospital to a private hospital. Concerning workplace

changes, participants were asked whether they

and/or their partners had begun to work from home;

they were then asked to describe the impact of the

change on their pregnancy experience. Concerning

mask-wearing practices, participants were asked

about their pattern and type of mask use. With

respect to travel and quarantine, participants

were asked whether they had travelled because of

COVID-19 risk; they were also asked about their

experiences with COVID-19 testing and quarantine.

Regarding the importance of birth companionship

and visiting hours, as well as the acceptance of service

adjustments and relief measures, participants were

asked to rate their opinions of these factors using a

visual analogue scale of 0 to 100, with 100 as very

important or strongly accepted.

Women with gestational age ≤24 weeks

were regarded as the early gestational group,

while women with gestational age >24 weeks and

women in the postnatal period were regarded as

the late gestational group. The COVID-19 alert

was announced by the Hong Kong government on

4 January 2020, slightly more than 20 weeks prior

to the commencement of this study. Women in the

early gestational group conceived after the date of

COVID-19 alert announcement, while women in

the late gestational group were already pregnant

on the announcement date. Statistical analysis was

performed using SPSS software (Windows version

26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

The distributions of continuous variables were

checked for normality. Analysis of variance and t

test assessments were used for normally distributed

variables, while the Mann-Whitney U test was used

for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical

variables were evaluated by the Chi squared test

or Fisher’s exact test. Regression analysis was

performed to examine the effects of marital status,

ethnic background, parity, and mental illness on the

behaviours of pregnant women regarding antenatal

appointment rescheduling and their opinions of

obstetric service adjustments. A value of P<0.05 was

considered significant.

Results

In total, 1000 information leaflets were distributed to 200 women in obstetric wards and 800 women

in out-patient clinics. In all, 890 responses were

registered online, including 878 women who

consented to participate and 12 women who did not

consent. Among women who agreed to participate,

145 did not finish the survey; thus, 733 completed

responses were available for analysis.

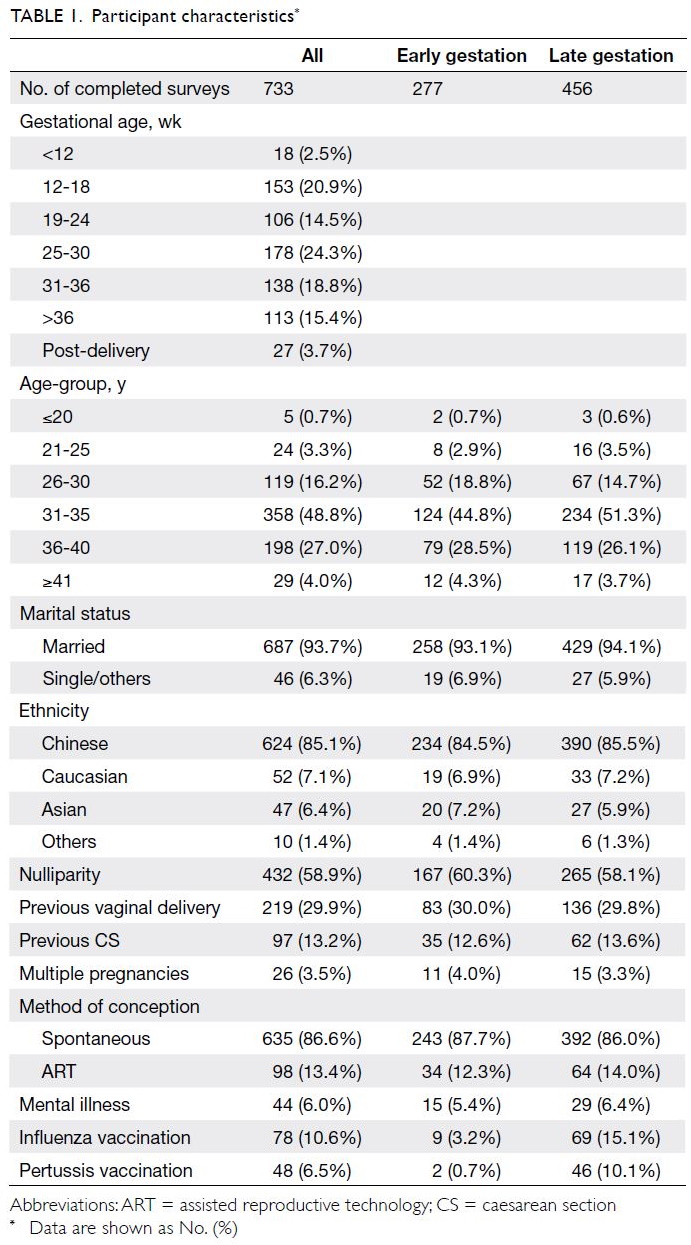

Table 1 shows the basic demographic

characteristics of the participants. Women aged

31 to 35 years constituted nearly half (48.8%) of

the respondents. The largest gestational age-group

was 25 to 30 weeks (24.3%). With the exception

of influenza and pertussis vaccination histories,

other background characteristics were comparable

between early and late gestational groups.

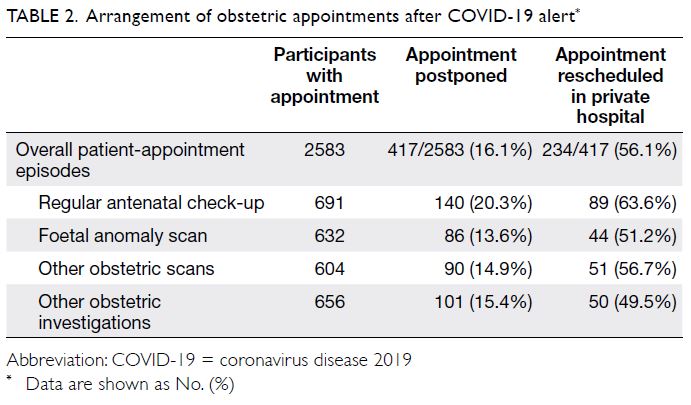

Obstetric appointment scheduling

Among 2583 patient appointments, 417 (16.1%)

were postponed or cancelled by pregnant women.

Over half (56.1%) of these were rescheduled to

a private hospital. The rate of postponement or

cancellation was higher for regular antenatal

visits (20.3%) and lower for foetal anomaly scans

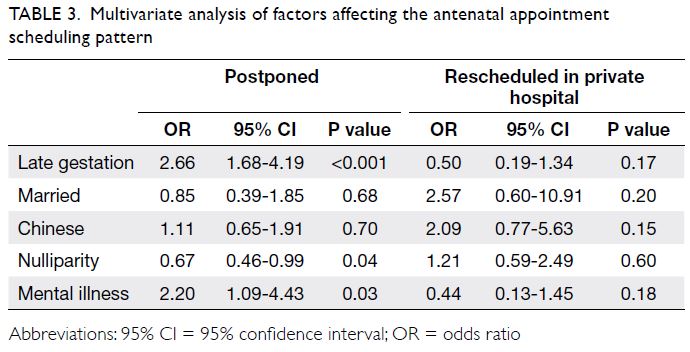

(13.6%) [Table 2]. Multivariate analysis showed that

women in the late gestational group (odds ratio

[OR]=2.66; 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.68-4.19;

P<0.001) and women with mental illness (OR=2.20; 95% CI=1.09-4.43; P=0.03) were more likely to

postpone or cancel regular antenatal appointments,

while nulliparous women (OR=0.67; 95% CI=0.46-0.99; P=0.04) were less likely to make such changes

(Table 3). No significant associations of demographic

characteristics with ultrasound and investigation

appointments (blood test, screening of Down’s

syndrome, or Group B streptococcus colonisation)

were identified.

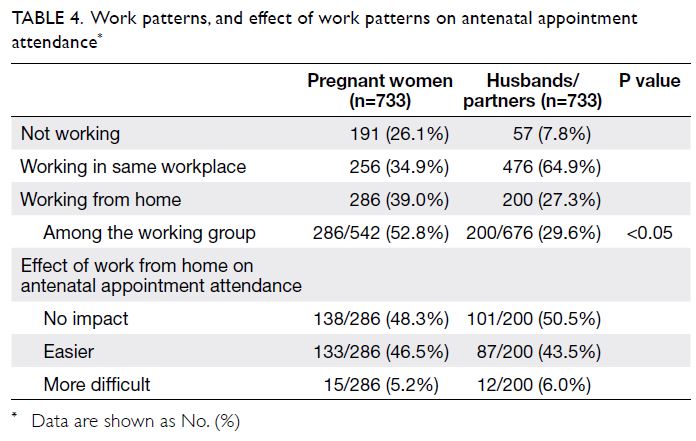

Working from home

As shown in Table 4, there were 542 (73.9%) working

women in this study; more than half of them began

working from home after the COVID-19 alert

announcement. Compared with their husbands/partners, significantly more women were working

from home (29.6% vs 52.8%; P<0.05). Among

women working from home, this work pattern facilitated obstetric appointment attendance for

46.5% (133/286) of the women and 43.5% (87/200)

of their husbands/partners. There was a tendency

for decreased omission of antenatal appointments

among women working at home, compared with

women working in usual workplaces, although the

differences were not statistically significant for any

type of appointment (antenatal check-up 6.6% vs

6.7%, P=0.10; anomaly scan 3.7% vs 8.0%, P=0.09;

obstetric scan 3.5% vs 6.6%, P=0.22; obstetric

investigations 5.1% vs 8.3%, P=0.30).

Overall pregnancy experience

Among the 131 women who reported that both they

and their husbands/partners worked from home,

107 (81.7%) reported a better overall pregnancy

experience. Among the 224 women who reported

that they or their husbands/partners worked from

home, 139 (62.1%) felt this work arrangement had

made their overall pregnancy experience better while

13 (5.8%) felt this had made their experience worse.

A significantly greater proportion of respondents

reported a much better overall pregnancy experience

when both they and their husbands/partners were

working from home than when either they or their

husbands/partners were working from home (50.4%

vs 31.7%; P=0.001). In contrast, suspension of school

and community services had more negative impacts

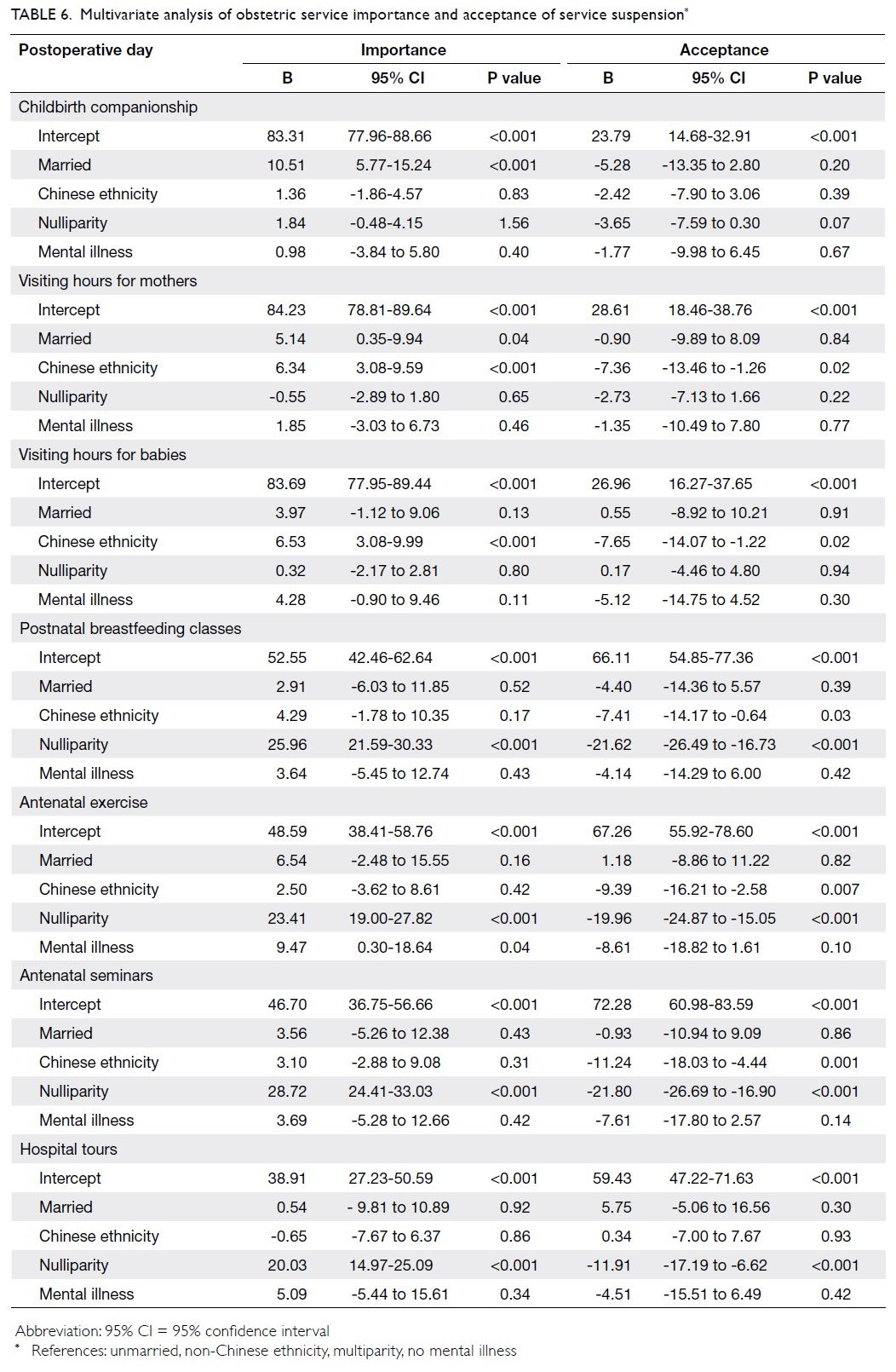

on pregnancy experience (Table 5).

Table 5. Effect of work pattern, school suspension, and community service suspension on overall pregnancy experience

More time to spend at home was selected by

80.1% (197/246) of the respondents as a beneficial

effect of working from home on their pregnancy

experience (online supplementary Table 3). Among

18 women who had a worse pregnancy experience

because of working from home, more psychological

stress was chosen by 13 (72.2%) women as one of the

underlying reasons. Five (27.8%) women reported

greater conflict with their husbands/partners because

of working from home (online supplementary Table 4).

Mask-wearing practices

The mean proportion of mask-wearing time was

significantly greater in clinical areas (97.2% for

hospitals and 97.0% for clinics) than in outdoor

areas (89.3%) and at home (4.1%, P<0.05). Over

90% of respondents always wore masks in clinical

areas; 63.8% always wore masks outdoors, and 0.8%

always wore masks at home. Among all women in

the study, surgical masks were most commonly

used; N95 masks were used by 55 (7.5%) women

in hospitals and 32 (4.4%) women in clinics (online supplementary Table 5).

Travel and quarantine experiences

Since the announcement of the COVID-19 alert,

6.8% (50/733) of respondents had travelled abroad because of COVID-19 risk in Hong Kong; 13.4%

(98/733) of respondents had returned to Hong Kong

because of COVID-19 risk abroad. Additionally, 31

(4.2%) women had been quarantined and 26 (3.5%)

women had lived with household members during

home quarantine. Coronavirus disease 2019 testing

had been performed in 3.7% of all respondents.

Moderate to marked emotional disturbance related

to personal quarantine experience was reported by

64.5% (20/31) of the women (online supplementary Table 6).

Adjustments of birth companionship and

visiting hours

Husband/partner companionship during childbirth

was regarded as the most important obstetric service,

followed by visiting hours for pregnant women and

neonates. Childbirth companionship was considered

important by 88.1% of the respondents; only 4.2%

of the respondents fully accepted its suspension.

In contrast, suspension of hospital tours was fully

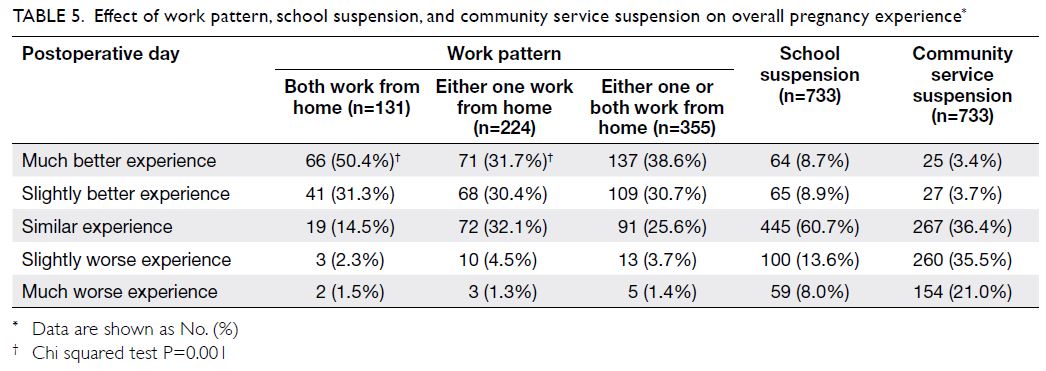

accepted by 27.0% of the respondents (online supplementary Fig). Univariate analysis showed

that marital status, ethnicity, parity, and history of

mental illness were factors that influenced opinions

of obstetric service importance and acceptance of

service suspension. Regression analysis showed that

being married was strongly associated with greater

perceived importance of childbirth companionship

(B=10.51; 95% CI=5.77-15.24) and visiting hours

for mothers (B=5.14; 95% CI=0.35-9.94). Chinese

women had the greatest perceived importance of

visiting arrangements for both mothers and babies;

they had the least acceptance of suspension of those

services. Nulliparity was only factor significantly

associated with the perceived importance of

antenatal exercise (B=23.41; 95% CI=19.00-27.82),

antenatal seminars (B=28.72; 95% CI=24.41-33.03),

hospital tours (B=20.03; 95% CI=14.97-25.09),

and postnatal breastfeeding classes (B=25.96;

95% CI=21.59-30.33) [Table 6].

Discussion

Summary

To our knowledge, this is the first study of the behavioural adaptations and responses to obstetric

care among pregnant women during an early stage

of the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong, a city

which previously experienced SARS outbreaks in

2002-2003. Approximately 16% of obstetric-related

appointments in public hospitals were postponed or

cancelled by pregnant women because of COVID-19,

but only 56% of these appointments were

rescheduled in private hospitals. Women who had

previous deliveries and a history of mental illness

were more likely adjust their appointments. Working

from home during the COVID-19 pandemic

improved the overall pregnancy experience in most

respondents. However, approximately 5% of women

reported negative impacts on their pregnancy

experiences, primarily because of psychological

stress. Concerning obstetric services, nearly 90% of

the women considered childbirth companionship

to be important; <5% of the women fully accepted

its suspension. More than 80% of the respondents

regarded visiting for mothers and newborns as

very important aspect of the overall pregnancy

experience. Obstetric service adjustments had the

greatest impact on Chinese women and nulliparous

women.

Antenatal care

Delays in seeking medical attention for acute medical

conditions such as cardiac and cerebrovascular

events were reported in 2020.14 15 16 Importantly,

failure to attend scheduled antenatal care can lead to

adverse outcomes.17 18 Women in the late gestational

group were already pregnant on the date of the

COVID-19 alert announcement; they might

have reported more adjustments to obstetric

appointments. Additionally, their shifts in obstetric

care and avoidance of in-hospital stays in public hospitals might be reflected by the reduced

delivery rate.19 Because of their previous pregnancy

experience, multiparous women might have been

more likely to modify antenatal appointments.

In contrast, women with mental illness require

greater antenatal care and psychosocial support.20

The establishment of virtual clinics for online

assessment without exposing pregnant women to

COVID-19 risk in clinical areas offers an important

alternative.21 To establish such clinics, antenatal

protocols must be revised to incorporate virtual

visits when ultrasounds, physical examinations, and

obstetric investigations are unnecessary. Pregnant

women would also require stable internet access, as

well as foetal doppler and blood pressure monitoring

equipment.

Working from home

Prior to and during the survey period, no complete

lockdowns were instituted in Hong Kong, although

working from home was encouraged. In this study,

slightly more than half of working women were

working from home after the COVID-19 alert.

There is a need to consider safety for women who

reported greater conflict with their husband/partner

while working from home. Increased domestic

violence was observed during the early stages of the

COVID-19 pandemic; greater relationship friction

and household conflict could be contributing

factors.22 Public policy should be revised to facilitate

the identification of women in need of conflict

assistance when physical and psychosocial support

may be limited because of physical isolation and the

suspension of community services.9 23

Behavioural adaptations

In this study, >90% of pregnant women reported

wearing a mask in clinical areas, although <10%

reported wearing an N95 mask in hospitals. Our

finding of 90% mask usage in clinical areas was much

greater than the 31.8% observed among the general

public in Taiwan in 2020.3 While the high rate of mask

use could represent compliance with hospital policies

regarding mandatory mask use and heightened

awareness of self-protection in pregnant women,

the use of N95 masks might also indicate a fear of

contacting COVID-19 in public hospitals where

confirmed cases were managed. Additionally, >20%

of the women either travelled abroad or returned to

Hong Kong because of COVID-19 risk. The history

of SARS outbreaks in Hong Kong might have led to

increased caution from the initial announcement of

the COVID-19 alert. Travel during pregnancy and

changes in delivery plans are important decisions.

In 2020, a study in China showed that women were

generally more anxious than men with respect to

COVID-19; greater perceived susceptibility and severity of COVID-19 were also associated with

greater anxiety.5 Obstetric decision-making and the

implementation of preventive measures have been

associated with antenatal anxiety secondary to the

COVID-19 pandemic.3 8 Quarantine can lead to

widespread and long-lasting adverse psychological

sequelae.24 In 2020, anxiety levels were significantly

higher among people who personally knew at least

one person with COVID-19.1 In our cohort, moderate

to marked emotional disturbance was reported by

two-thirds of women who had undergone quarantine

and one-third of women who had been living with

household members during home quarantine. There

is a need for supportive counselling to be provided to

this susceptible group of women.

Expectations of childbirth companionship

and peripartum services

Women’s expectations did not match changes in peripartum services and childbirth companionship;

these mismatches were greatest in married women.

Childbirth companionship provides multiple types

of physical and psychological support.25 Women of

Chinese ethnicity exhibited the greatest disagreement

with suspension of visiting hours. The principle

of “doing the month” in Chinese culture promotes

maternal rest with nutritious supplements; thus,

visits during the postpartum period are regarded

as essential convalescence for mothers and babies.26

In Hong Kong, a greater proportion of women had

a higher Edinburg Postpartum Depression Scale

score upon suspension of childbirth companionship

and visiting hours after announcement of the

COVID-19 alert.19 In 2020, a similar effect on the

Edinburg Postpartum Depression Scale score was

observed in a Turkish population.27 Importantly,

the Comprehensive Child Development Service in

public obstetric units provides a programme for the

identification, follow-up, and counselling of women

at risk of postpartum depression; this programme

constitutes critical support during stressful periods,

such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Strengths and limitations

Likely because many women of reproductive age

living in Hong Kong remember the SARS outbreaks

in 2002-2003, a notable strength was that the present

study provided a useful assessment of adaptations

and responses to a similar disease (COVID-19). Such

valuable information can improve the understanding

of behaviour among pregnant women in places that

encounter further waves of COVID-19 transmission.

The merit of this survey was that the online

questionnaire format allowed respondents to

complete the questionnaire remotely and at their

preferred speed. The responses were automatically

captured in a database, which minimised entry errors and potential transmission of COVID-19.

However, this questionnaire format is limited to

patients with electronic access and does not permit

the involvement of an interviewer to explain the

questions. The use of convenience sampling in a

single centre might also have introduced bias and

limited the generalisability of the findings to the

general population.

An additional limitation was that only women

who continued antenatal follow-up or delivered in

our public hospital were included in the present

study. The delivery rate for January to April

decreased by 13% in 2020, compared with the same

period in 2019, despite a similar number of delivery

bookings.17 This phenomenon was observed across

all public hospitals in Hong Kong, indicating that

pregnant women might have chosen to deliver in

private hospitals instead. There is no standalone

maternity hospital in Hong Kong; all maternity

units are housed within general hospitals that admit

patients with COVID-19. We suspect that this

situation might have led some pregnant women to

deliver in private hospitals where they perceived the

risk of COVID-19 to be lower.

The final limitation was that the survey was

conducted during a non-peak period of COVID-19

transmission in 2020. Childbirth companionship

was resumed 2 days prior to the survey period;

companions were required to complete an

assessment of fever, travel, occupational exposure,

contact history, and clustering phenomenon. Thus,

the practices might have differed and the overall fear

of disease might have been less intense, compared

with a peak period of COVID-19 transmission.

Furthermore, the retrospective nature of this

study might have introduced recall bias, which

we attempted to minimise by providing a timeline

of key events concerning COVID-19 in the

information leaflet. However, the initial response of

the general public to COVID-19 might have been

exaggerated because accurate disease information

was limited during the early stages of the pandemic;

the performance of a questionnaire study during

a non-peak period might have helped to gather

less exaggerated data concerning the behaviour of

pregnant women. Further prospective longitudinal

studies can address how women respond in different

phases of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the adaptations and

responses of pregnant women to the COVID-19

pandemic in Hong Kong. The women in this study

adjusted their obstetric appointments, began to

work from home, and practised protective measures

to reduce their risk of disease. While the overall

pregnancy experience was mostly improved by

working from home, women reported emotional disturbance because of the pandemic. Expectations

of obstetric services remained high, particularly

for Chinese women and nulliparous women.

Obstetricians and policymakers should attempt to

balance infection control and the peripartum needs

of pregnant women when modifying childbirth

companionship policies. Particular attention

to nulliparous women is needed because they

demonstrated higher levels of disagreement with the

suspension of antenatal and postnatal educational

programmes.

Author contributions

Concept or design: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PW Hui.

Drafting of the manuscript: PW Hui.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: All authors.

Analysis or interpretation of data: PW Hui.

Drafting of the manuscript: PW Hui.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Ms WK Choi for her assistance with creation of the online survey and Mr G Chu for his assistance

with participant recruitment.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The research has been approved by Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority

West Cluster (Ref UW 20-387).

References

1. Moghanibashi-Mansourieh A. Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatr 2020;51:102076. Crossref

2. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological

responses and associated factors during the initial stage

of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic

among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res

Public Health 2020;17:1729. Crossref

3. Wong LP, Hung CC, Alias H, Lee TS. Anxiety symptoms

and preventive measures during the COVID-19 outbreak

in Taiwan. BMC Psychiatry 2020;20:376. Crossref

4. Corbett GA, Milne SJ, Hehir MP, Lindow SW,

O’Connell MP. Health anxiety and behavioural changes of

pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J

Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;249:96-7. Crossref

5. Lin Y, Hu Z, Alias H, Wong LP. Knowledge, attitudes,

impact, and anxiety regarding COVID-19 infection among

the public in China. Front Public Health 2020;8:236. Crossref

6. Ozamiz-Etxebarria N, Dosil-Santamaria M, Picaza-Gorrochategui M, Idoiaga-Mondragon N. Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19

outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain [in

Spanish]. Cad Saude Publica 2020;36:e00054020.

7. Kotlyar AM, Grechukhina O, Chen A, et al. Vertical

transmission of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;224:35-53.e3.

8. Liu X, Chen M, Wang Y, et al. Prenatal anxiety and

obstetric decisions among pregnant women in Wuhan

and Chongqing during the COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional

study. BJOG 2020;127:1229-40. Crossref

9. Thapa SB, Mainali A, Schwank SE, Acharya G. Maternal

mental health in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2020;99:817-8. Crossref

10. Wu Y, Zhang C, Liu H, et al. Perinatal depressive and

anxiety symptoms of pregnant women along with COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;223:240.e1-9.

11. Westgren M, Pettersson K, Hagberg H, Acharya G.

Severe maternal morbidity and mortality associated with

COVID-19: the risk should not be downplayed. Acta

Obstet Gynecol Scand 2020;99:815-6. Crossref

12. Leung GM, Cowling BJ, Wu JT. From a sprint to a marathon

in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med 2020;382:e45.

13. To KK, Yuen KY. Responding to COVID-19 in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong Med J 2020;26:164-6.

14. Metzler B, Siostrzonek P, Binder RK, Bauer A, Reinstadler SJ.

Decline of acute coronary syndrome admissions in Austria

since the outbreak of COVID-19: the pandemic response

causes cardiac collateral damage. Eur Heart J 2020;41:1852-3. Crossref

15. Teo KC, Leung WC, Wong YK, et al. Delays in stroke onset to hospital arrival time during COVID-19. Stroke

2020;51:2228-31. Crossref

16. Marijon E, Karam N, Jost D, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac

arrest during the COVID-19 pandemic in Paris, France:

a population-based, observational study. Lancet Public

Health 2020;5:e437-43.

17. Vogel JP, Habib NA, Souza JP, et al. Antenatal care packages with reduced visits and perinatal mortality: a secondary analysis of the WHO Antenatal Care Trial. Reprod Health

2013;10:19. Crossref

18. Mohamed Shaker El-Sayed Azzaz A, Martínez-Maestre MA,

Torrejón-Cardoso R. Antenatal care visits during

pregnancy and their effect on maternal and fetal outcomes

in pre-eclamptic patients. J Obstet Gynaecol Res

2016;42:1102-10. Crossref

19. Hui PW, Ma G, Seto MT, Cheung KW. Effect of COVID-19

on delivery plan and postnatal depression score of pregnant

women. Hong Kong Med J 2021;27:113-7.

20. Berthelot N, Lemieux R, Garon-Bissonnette J, Drouin-Maziade C, Martel É, Maziade M. Uptrend in distress and psychiatric symptomatology in pregnant women during

the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Acta Obstet

Gynecol Scand 2020;99:848-55. Crossref

21. Aziz A, Zork N, Aubey JJ, et al. Telehealth for high-risk

pregnancies in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am

J Perinatol 2020;37:800-8. Crossref

22. Roesch E, Amin A, Gupta J, García-Moreno C. Violence against women during COVID-19 pandemic restrictions.

BMJ 2020;369:m1712.

23. Usher K, Bhullar N, Durkin J, Gyamfi N, Jackson D.

Family violence and COVID-19: increased vulnerability

and reduced options for support. Int J Ment Health Nurs

2020;29:549-52. Crossref

24. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological

impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of

the evidence. Lancet 2020;395:912-20. Crossref

25. Bohren MA, Berger BO, Munthe-Kaas H, Tunçalp Ö.

Perceptions and experiences of labour companionship:

a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev 2019;(3):CD012449.

26. Liu YQ, Maloni JA, Petrini MA. Effect of postpartum

practices of doing the month on Chinese women’s physical

and psychological health. Biol Res Nurs 2014;16:55-63. Crossref

27. Durankuş F, Aksu E. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic

on anxiety and depressive symptoms in pregnant women:

a preliminary study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med

2020;35:205-11. Crossref