Hong Kong Med J 2022 Aug;28(4):285–93 | Epub 21 Jan 2022

© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Stillbirth rate in singleton pregnancies: a 20-year

retrospective study from a public obstetric unit in Hong Kong

Sani TK Wong, MB, ChB; WT Tse, MB, ChB, MRCOG; SL Lau, MB, ChB, MRCOG; Daljit S Sahota, PhD; TY Leung, MD, FRCOG

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof TY Leung (tyleung@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: Although the stillbirth rate is

low in Hong Kong, up to 50% of stillbirths have

unclassifiable causes and up to one third of stillbirths

have unexplained causes. This retrospective study

investigated the underlying causes of singleton

stillbirths in Hong Kong.

Methods: This study examined the prevalences and

causes of stillbirths in a university tertiary obstetric

unit between 2000 and 2019. Medical records were

reviewed for all singleton pregnancies complicated

by stillbirths. Causes of stillbirth were determined

via clinical assessments and laboratory findings,

then compared between 2000-09 and 2010-19.

Results: Overall perinatal mortality significantly

decreased by 16.7%, from 5.50/1000 in 2000-09 to

4.59/1000 in 2010-19; the singleton stillbirth rate

slightly decreased (from 3.27/1000 to 2.91/1000).

These changes were related to early prenatal

diagnostic improvements concerning congenital

malformations and genetic disorders. Pre-eclampsia

prevalence among singleton pregnancies increased

from 1.5% to 1.7% because of increasing maternal

age; the stillbirth rate among patients with pre-eclampsia

decreased from 2.5% to 1.4%. Foetal

growth restriction of unknown cause contributed to 16% of all stillbirths; this prevalence did not change

over time. Moreover, foetal growth restriction was

not diagnosed during routine antenatal care in 43.5%

of patients. Thirty-six percent of all stillbirths were

unexplained. The prevalences of stillbirth associated

with chorioamnionitis and placental abruption did

not change over time.

Conclusions: Causes of stillbirth in Hong Kong have changed in the past 20 years because of altered

demographic characteristics and improved prenatal

testing. Further improvements should focus on

early foetal growth restriction detection and preeclampsia

prevention.

New knowledge added by this study

- The stillbirth rate among singleton pregnancies in Hong Kong is declining (from 3.27/1000 in 2000-09 to 2.91/1000 in 2010-19), mainly because of reductions in congenital malformations and genetic diseases.

- Pre-eclampsia is becoming more prevalent (from 1.5% in 2000-09 to 1.7% in 2010-19), although the pre-eclampsia–related stillbirth rate has decreased (from 2.5% to 1.4%).

- Foetal growth restriction (FGR) remains a common cause of stillbirths (16% of all stillbirths), and 43.5% of FGR-related stillbirths were undiagnosed during routine antenatal care.

- Primary prevention of pre-eclampsia through first trimester screening and aspirin prophylaxis is essential for improving maternal and foetal health.

- Antenatal detection of FGR should be improved using more accurate sonographic and biochemical tests.

- Territory-wide perinatal mortality monitoring is important for maintaining the standard of perinatal care in Hong Kong.

Introduction

Compared with many other regions worldwide,

Hong Kong has one of the lowest perinatal mortality

rates, defined as the total number of stillbirths and

early neonatal deaths per 1000 births.1 Worldwide,

there are consistent definitions of early and late neonatal deaths (ie, the death of a livebirth in the first

7 days and 28 days after birth, respectively); however,

the definition of stillbirth varies among regions.

Hong Kong has been using the United Kingdom’s

definition of stillbirth, which is ‘a baby delivered with

no signs of life at or after 24 weeks of gestation’.1 In contrast, some countries use 20 weeks, 22 weeks, or

500 g as a threshold for stillbirth.2 To facilitate global

comparisons, the World Health Organization has

stratified stillbirth into early (death at a birthweight

>500 g or at a gestational age ≥22 weeks) and late

foetal death (death at a birthweight ≥1000 g or at a

gestational age ≥28 weeks).3

The estimated global stillbirth rate was

18.4/1000 births in 2015.4 Estimated stillbirth

rates are significantly lower in developed countries

(approximately 3.4/1000 births); the highest stillbirth

rate has been reported in sub-Saharan Africa regions

(28.7/1000 births).4 Intrapartum stillbirths comprise

up to 57% of all reported stillbirths in South Asia;

most are related to obstetric emergencies.5 Thus, the

stillbirth rate is a potential indicator of a country’s

healthcare system quality; variations in intrapartum

stillbirth rates among countries may reflect the

readiness of health facilities to provide adequate

intrapartum care and ensure that trained birth

attendants are available for delivery.5 Therefore, the

United Nations has included stillbirth prevention as

a major Sustainable Development Goal.6

The stillbirth rate is consistently low in

Hong Kong (2/1000 births during the period from

2004 to 2014).1 However, up to 50% of stillbirths

have unclassifiable causes and up to one third of

stillbirths have unexplained causes, which may

reflect inconsistencies and limitations regarding the different coding systems that are used by obstetric

units in Hong Kong.

This study was performed to review the

overall perinatal mortality in a tertiary centre in

Hong Kong, and specifically explored the causes,

the associated risk factors and trends of stillbirth in

singleton pregnancies. Neonatal deaths and perinatal

mortalities in multiple pregnancies will be reported

separately.

Methods

Study setting

This study retrospectively reviewed data collected

from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2019, in the

Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong Kong. The hospital

serves a population of approximately 1.7 million

in the New Territories East region of Hong Kong,

with an annual delivery rate of approximately 6000

to 7000 births. The obstetric unit is also a tertiary

centre that receives complicated maternal and foetal

cases referred from other hospitals as well as a

maternal foetal medicine training centre accredited

by both The Royal College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists (https://www.rcog.org.uk) and

The Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists (www.hkcog.org.hk). The standard

antenatal and obstetric care, as well as the

investigation of stillbirth and neonatal death are

described in the Supplementary Appendix.

Data collection and analysis

Data of all deliveries including maternal demographic data (eg, ethnicity, maternal age, height, body weight,

body mass index [BMI], underlying medical diseases,

and obstetric history), obstetric and perinatal

outcomes were retrieved from a hospital-specific

Obstetric Specialty Clinical Information System that

is used to record maternal and perinatal outcomes

after birth.7 Stillbirths (defined as foetal death that

occurred at or after 24 weeks; late stillbirth occurred

at or after 28 weeks)3 were identified from the

database and their details were further retrieved

from hospital electronic records. All stillbirths

were included regardless of their booking status

or whether their deaths were occurred before

admission to our unit; however, the booking status

was incorporated into the analysis.

The stillbirth rate was calculated as the number

of stillbirths divided by the total number of births

(after 24 weeks). The stillbirth rates of singleton

pregnancies were compared between 2000-09 and

2010-19.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared by the

independent samples t test or Mann-Whitney

U test for parametric and non-parametric data, respectively. Categorical variables were compared

by the Chi squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as

appropriate. The level of significance was set at

a two-sided P value of <0.05. Data analysis was

performed using SPSS (Windows version 22.0; IBM

Corp, Armonk [NY], United States).

Results

Mortality during the study period

During the 20-year study period, there were 128 967

babies delivered. Among them were 429 stillbirths,

159 early neonatal deaths, and 59 late neonatal

deaths. The total mortality rate was 5.02 per 1000

births and the perinatal mortality rate was 4.56 per

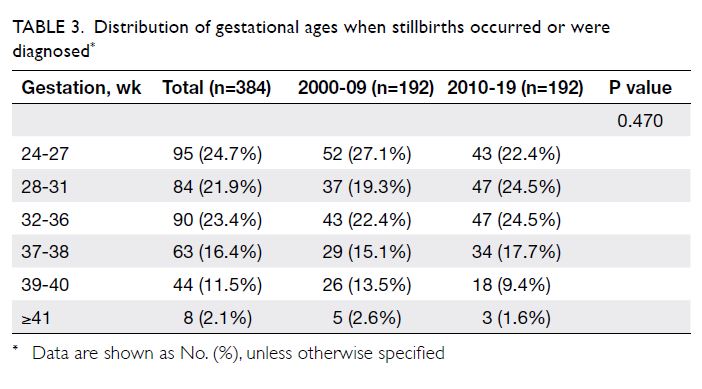

1000 births. The total mortality rate was significantly

lower during 2010-19 than during 2000-09 (4.59

per 1000 births vs 5.50 per 1000 births; P=0.023).

The perinatal mortality rate was also significantly

lower in 2010-19 (4.18 per 1000 births vs 5.00 per

1000 births; P=0.035), although the rates of stillbirths

and late stillbirths were not significantly different

between 2000-09 and 2010-19 (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of stillbirth rates, neonatal death (NND) rates, and total and perinatal mortality rates (per 1000 births) among both singleton and multiple pregnancies between 2000-09 and 2010-19

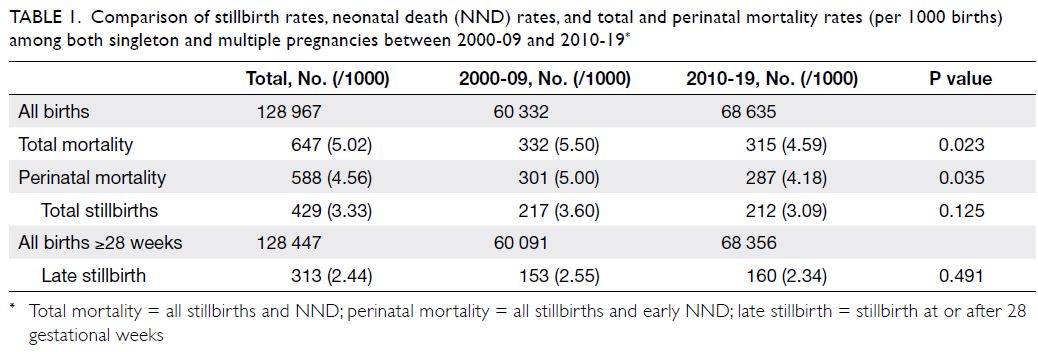

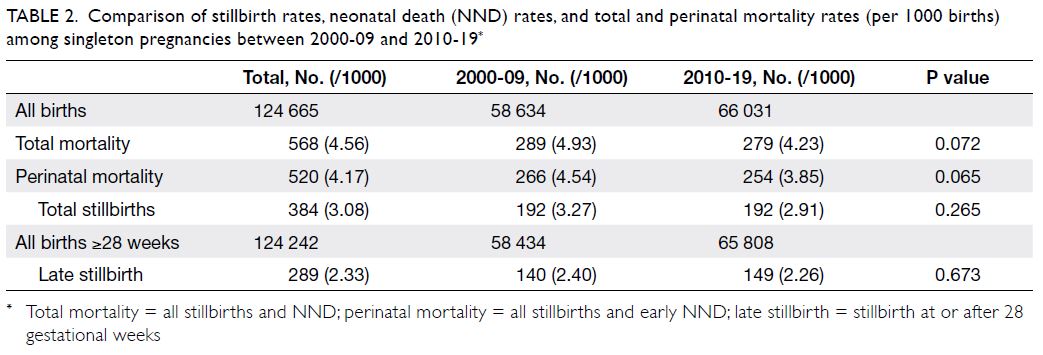

Table 2 shows all mortality data for singleton

pregnancies. Among 124 665 singleton babies,

the respective total mortality, perinatal mortality

and stillbirth rates were 4.56/1000, 4.17/1000 and

3.08/1000. Among the 384 singleton stillbirths, 95 (24.7%) occurred between 24 and 27 weeks,

while 289 (75.3%) occurred thereafter; thus, the

late stillbirth rate was 2.33/1000. The detailed

distribution of gestational ages among stillbirths

is shown in Table 3. There were 23 (6%) cases of

intrapartum death (0.18/1000 births); these were

caused by placental abruption (n=11), known lethal

foetal anomalies (n=7), chorioamnionitis (n=2),

uterine rupture (n=1), maternal diabetic ketoacidosis

(n=1), and umbilical cord accident—cord ulceration

related to duodenal atresia (n=1).8

Table 2. Comparison of stillbirth rates, neonatal death (NND) rates, and total and perinatal mortality rates (per 1000 births) among singleton pregnancies between 2000-09 and 2010-19

Singleton stillbirths: causes and potential risk

factors

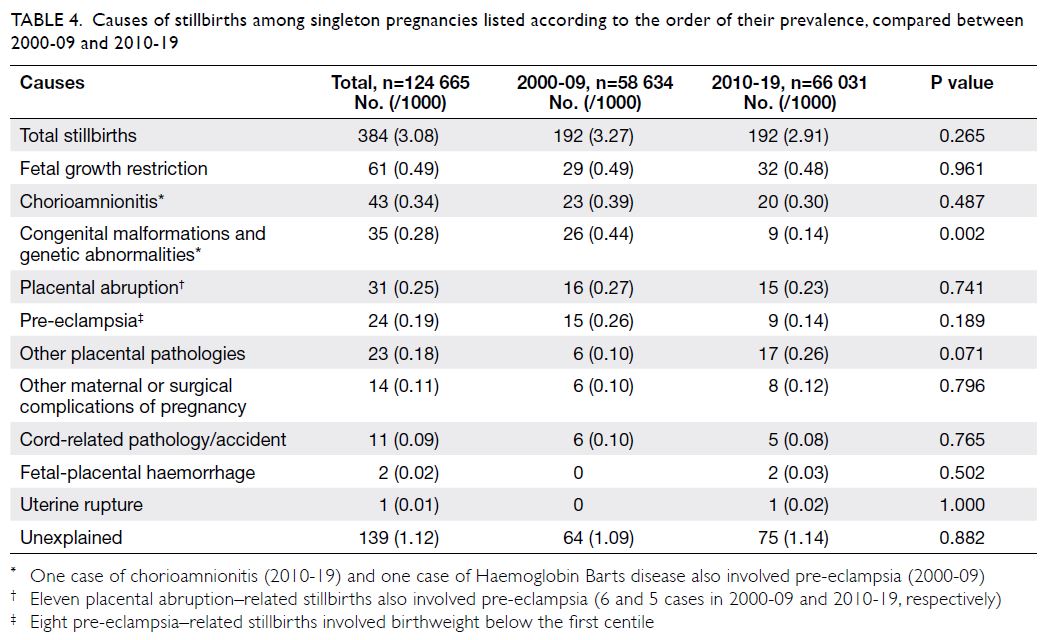

Table 4 shows the direct causes of the 384 singleton stillbirths that occurred during the study period.

The most common leading cause was foetal

growth restriction (FGR) [n=61, 15.9% of singleton

stillbirths]; 41 of these 61 cases (67.2%) were not

diagnosed before birth. The next most common

leading causes were chorioamnionitis (n=43, 11.2%

of singleton stillbirths), congenital malformations

and genetic abnormalities (n=35, 9.1% of singleton

stillbirths), placental abruption (n=31, 8.1% of

singleton stillbirths), and pre-eclampsia (n=24, 6.3%

of singleton stillbirths). Pre-eclampsia also occurred

in 11 cases of placental abruption, one case of genetic abnormality (Haemoglobin Barts), and one case of

chorioamnionitis; importantly, pre-eclampsia was

not regarded as the leading cause in these 13 cases.

There were 139 unexplained stillbirths and

comprised about one third of all singleton stillbirths.

Table 4. Causes of stillbirths among singleton pregnancies listed according to the order of their prevalence, compared between 2000-09 and 2010-19

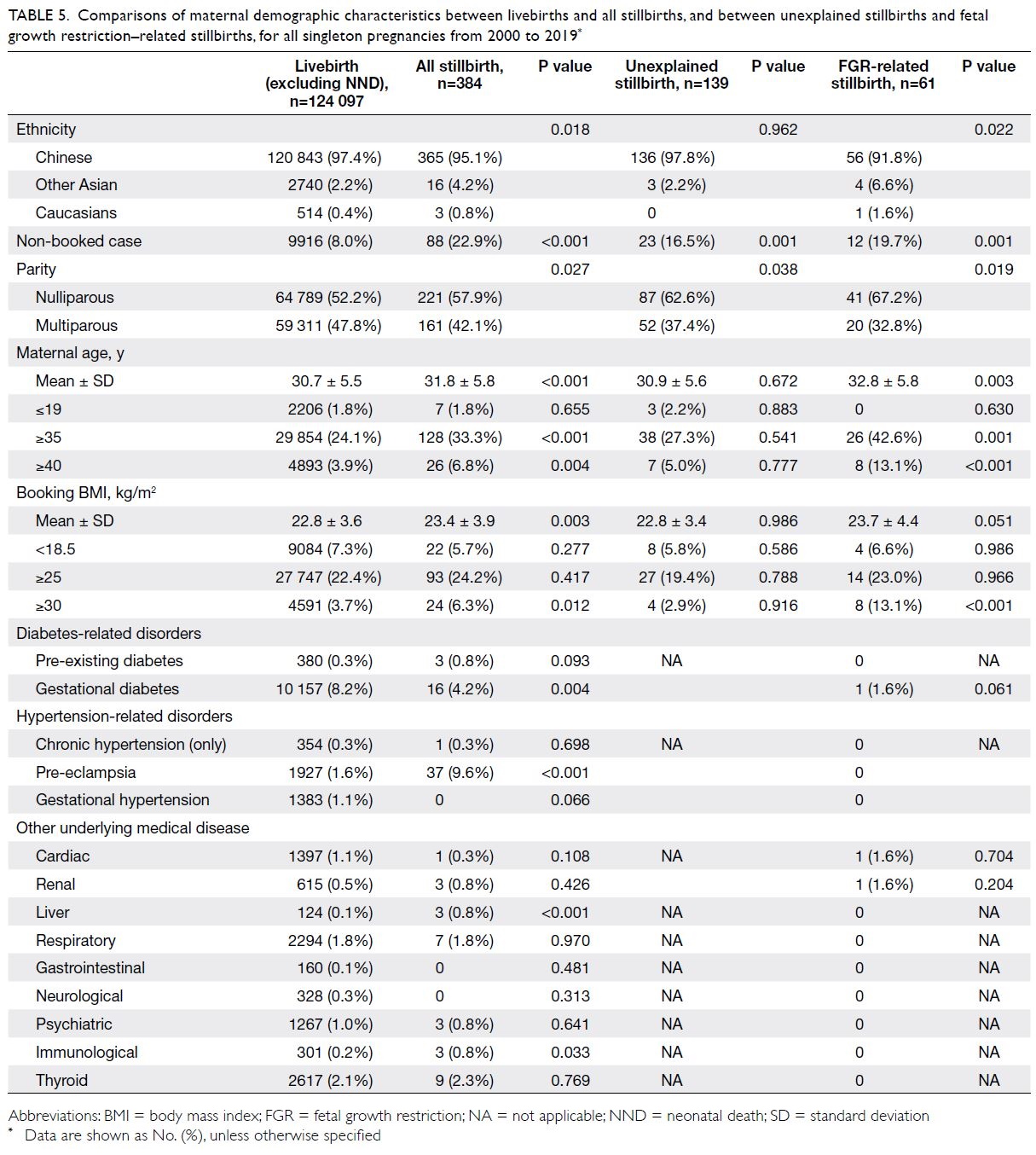

Table 5 shows the maternal characteristics for

all stillbirths and for the subgroups of unexplained

stillbirths and FGR-related stillbirths in singleton

pregnancies. Compared with mothers in the

livebirth group (excluding neonatal death), mothers

in the stillbirth group were significantly older

(30.7 ± 5.5 years vs 31.8 ± 5.8 years; P<0.001); greater

proportions of mothers in the stillbirth group had

advanced maternal age ≥35 years (24.1% vs 33.3%;

P<0.001) and ≥40 years (3.9% vs 6.8%; P=0.004).

Mothers in the stillbirth group also had higher BMI at booking (22.8 ± 3.6 kg/m2 vs 23.4 ± 3.9 kg/m2;

P=0.003); greater proportions of mothers in the

stillbirth group had BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (3.7% vs 6.3%;

P=0.012). The prevalences of nulliparity (52.2% vs

57.7%; P=0.027), non-booked status (8.0% vs 22.9%,

P<0.001), and non-Chinese Asian ethnicity (2.6%

vs 5%; P=0.018) were also significantly higher in

the stillbirth group. In the unexplained stillbirth

subgroup, only nulliparity and non-booked status

remained significant risk factors. In the FGR-related

stillbirth subgroup, the mothers were more likely

to be non-Chinese, non-booked cases, nulliparous,

older, and obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2).

Table 5. Comparisons of maternal demographic characteristics between livebirths and all stillbirths, and between unexplained stillbirths and foetal growth restriction–related stillbirths, for all singleton pregnancies from 2000 to 2019

Compared with the livebirth group, the

prevalences of several medical diseases were also

higher in the stillbirth group, including pre-eclampsia

(1.6% vs 9.6%; P<0.001), liver diseases (0.1% vs 0.8%;

P<0.001), and immunological diseases (0.2% vs 0.8%;

P=0.033). However, histories of other pre-existing

medical condition such as diabetes and chronic

hypertension were not associated with stillbirth.

There was a lower prevalence of gestational diabetes

(8.2% vs 4.2%; P=0.004) in the stillbirth group.

Changes in stillbirth causes and risk factors

over time

Comparing 2000-09 and 2010-19, there was a trend

towards reduction in stillbirth rate (3.27/1000 vs

2.91/1000; P=0.265), although this difference was

not statistically significant. Among the direct causes

of stillbirths, there was a significant reduction in

the prevalence of congenital malformations and genetic abnormalities (0.44/1000 vs 0.14/1000;

P=0.002). There was a trend towards reduction

in pre-eclampsia–related stillbirths (0.26/1000 vs

0.14/1000; P=0.189), although this difference was

not statistically significant. There was an increasing

trend of singleton stillbirths related to other placental

pathologies although it did not reach statistical significance (0.10/1000 vs 0.26/1000; P=0.071). The

prevalences of FGR, chorioamnionitis, placental

abruption, other maternal or surgical complications

of pregnancy, cord-related pathology/accident,

foetal-placental haemorrhage, uterine rupture, and

unexplained stillbirth did not change over time

(Table 4).

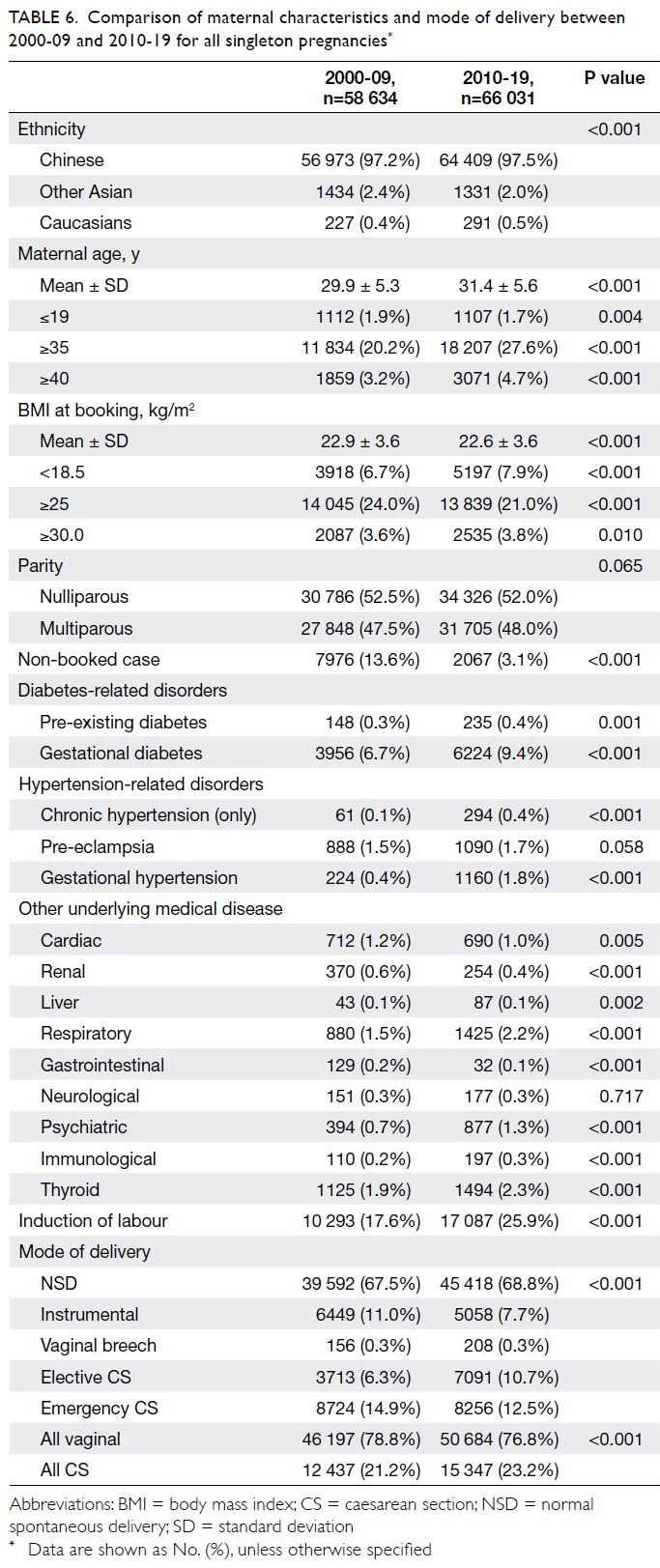

Between 2000-09 and 2010-19, there were

several significant changes in maternal demographics

(Table 6), including a higher maternal age over time

(29.9 ± 5.3 years vs 31.4 ± 5.6 years; P<0.001); in

2010-19, a greater proportion of mothers had

advanced maternal age ≥35 years (20.2% vs 27.6%;

P<0.001) and ≥40 years (3.2% vs 4.7%; P<0.001).

The mean booking BMI was significantly reduced

in 2010-19 (22.9 ± 3.6 kg/m2 vs 22.6 ± 3.6 kg/m2;

P<0.001), with greater prevalence of underweight

(BMI at booking <18.5 kg/m2; 6.7% vs 7.9%; P<0.001),

although a greater prevalence of obesity was also

observed (BMI at booking >30 kg/m2; 3.6% vs 3.8%,

P=0.01) [Table 6]. The prevalence of non-booked

cases was also significantly reduced (13.6% vs 3.1%;

P<0.001). Chinese ethnicity remained dominant

(97.2% vs 97.5%; P<0.001) and the proportions of

nulliparous mothers were similar (52.5% vs 52.0%;

P=0.065). In 2010-19, there were higher prevalence

of pre-existing diabetes (0.3% vs 0.4%; P=0.001),

gestational diabetes (6.7% vs 9.4%; P<0.001),

chronic hypertension (0.1% vs 0.4%; P<0.001) and

gestational hypertension (0.4% vs 1.8%; P<0.001);

the caesarean delivery rate also increased (21.2% vs

23.2%; P<0.001). Other changes in the prevalences of

medical diseases are summarised in Table 6.

Table 6. Comparison of maternal characteristics and mode of delivery between 2000-09 and 2010-19 for all singleton pregnancies

Discussion

Changes in perinatal mortality

This investigation of perinatal mortality in Hong

Kong showed that the overall perinatal mortality

rate was significantly reduced by 16.7% from

5.50/1000 in 2000-09 to 4.59/1000 in 2010-19. This

is a combined effect of reductions in stillbirths and

neonatal deaths, although these individual trends

(ie, rates of stillbirth and neonatal death) were not

significantly different over time. Compared with the

stillbirth rate of 4.44/1000 reported by our unit in

1994,9 we observed gradual declines to 3.60/1000

in 2000-09 and 3.09/1000 in 2010-19. Because our

hospital is a tertiary referral centre, it is reasonable

that our stillbirth rate is slightly higher than the rate

determined in a territory-wide audit performed

by the Hong Kong College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists (2/1000 births).1

The intrapartum death rate in Hong Kong was

considerably reduced from 0.96/1000 (22% of all

stillbirths) in the 1990s9 to 0.2/1000 in the present

study; intrapartum deaths only comprised 6% of

all stillbirths in our cohort. Our findings compare

favourably with the reported mean intrapartum

rates of 0.9/1000 and 7/1000 in developed and

developing countries, respectively, during the mid-2000s.10 Furthermore, approximately one third of

our intrapartum stillbirths involved congenital lethal

malformations; the patients had not undergone

intrapartum foetal monitoring and no active resuscitation had been performed after birth. Our

low intrapartum stillbirth rate was related to the

use of continuous foetal heart rate monitoring, as

well as short decision-to-delivery interval (median

10 minutes) and bradycardia-to-delivery interval

(median 11 minutes); these approaches have been

described in our previous reports.11 12 13

Changes in stillbirth causes and risk factors

In this study, we observed a significant decline

in stillbirths caused by congenital malformations

and chromosomal abnormalities since 2010. This

coincided with implementation of the universal first

trimester Down syndrome screening by the Hospital

Authority in 2010,14 15 16 as well as the provision of

non-invasive cell-free foetal DNA testing in private

sectors beginning in 2011.17 18 These two new

services might have various implications beyond

improvements in detection of foetuses with trisomy

21. The early detection of lethal malformations

and genetic disorders (eg, trisomy 18, trisomy 13,

and alpha-thalassemia major) was also improved.19

Because mothers were encouraged to undergo

earlier antenatal assessments, foetuses with those

lethal diseases were converted to legal abortions

earlier during pregnancy; instead of progressing

until stillbirth or neonatal death.

Pre-eclampsia is a known important causative

factor of foetal death.20 In this study, pre-eclampsia

was regarded as the leading cause of 24 stillbirths;

eight of these cases (33.3%) also had FGR that

contributed to birthweight below the first centile.

In addition, pre-eclampsia caused placental

abruption in another 11 stillbirths; co-existing pre-eclampsia

was present in one case of congenital

abnormality (Haemoglobin Barts) and one case of

chorioamnionitis. Therefore, the risk of stillbirth

in the presence of pre-eclampsia was increased by

six-fold, from 1.6% to 9.6% (Table 5). Although the

prevalence of pre-eclampsia increased from 1.5%

(888/58 634) in 2000-09 to 1.7% (1090/66 031)

in 2010-19 (Table 6), the pre-eclampsia–related

stillbirth rate decreased from 2.5% (22/888) to 1.4%

(15/1090). This reduction is probably related to

improvements in antenatal care, early detection,

and intervention (eg, iatrogenic preterm delivery).

Because increased pre-eclampsia prevalence is

related to advanced maternal age and obesity,7 21

primary prevention via first trimester screening

and aspirin prophylaxis is essential for preventing

adverse foetal outcomes in the future.22 23 24 25

We have noticed increasing rates of stillbirths

related to placental pathologies, such as villitis or

villous vasculopathy. Stillbirths were also associated

with FGR; approximately 30% of cases involved

birthweight below the third centile. Because

placentas of livebirths were not subjected to routine

histological examination, the prevalences of such pathologies remain unknown. Furthermore, these

cases were categorised only according to post-delivery

histology; the determinations were made

after exclusion of obvious clinical abnormalities

(eg, pre-eclampsia, medical diseases, congenital

disorders, and genetic disorders). Therefore, such

pathologies are challenging to diagnose prenatally

with the goal of preventing foetal death, unless

FGR is detected. Similarly, the 61 cases in the FGR

group involved stillbirths without obvious causes

of FGR. Their birthweight centiles were below first

centile, first to below third centile, and third to less

than fifth centile in 44 (72.1%), 16 (26.2%), and one

(1.6%) cases, respectively. However, a substantial

proportion of these cases (43.5%) were diagnosed

based on post-delivery birthweight alone, rather

than through prenatal assessments. Conventionally,

foetal growth is routinely monitored at intervals

of a few weeks by fundal height measurement in

public sector hospitals. Only high-risk patients

or suspected cases of FGR are monitored via

sonographic foetal biometric measurement. Further

service improvements should focus on increasing the

rate of FGR detection, while minimising the false-positive

rate using a combination of first trimester

biochemical markers.26 27 28 29 30 31

Unexplained stillbirths constituted 36.2% of

our stillbirth cohort, which is consistent with the

prevalences in other developed countries32; the

prevalence in our study did not substantially decrease

during the study period. With the exceptions of

nulliparity and non-admitted status, we were unable

to identify any maternal demographic factors that

contributed to this type of stillbirth. Unexplained

stillbirths were unrelated to extreme maternal

age or extreme maternal BMI (ie, underweight or

overweight). In 17.4% of these cases, the birthweight

centile was between the third and less than tenth

centile, which was much higher than expected.

These might have constituted more subtle cases of

FGR or late-onset FGR. Further studies are needed

to determine whether late-onset FGR or elective

induction of labour at 39 weeks can reduce the

stillbirth rate in Hong Kong. Chorioamnionitis,

placental abruption, and cord accidents are

unpredictable events; their prevalences among

stillbirths remained similar throughout the study

period.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the largest study

concerning the prevalence and causes of stillbirth

in Hong Kong with a 20-year study period. The

computerised database of the Hospital Authority

provided comprehensive information concerning

major risk factors, although it did not contain data

concerning maternal social factors (eg, smoking,

family income, and marital status). Clinical practice might have changed during the 20-year

study period; this might have led to modifications

regarding the classification of stillbirth causes. For

example, the shift from karyotyping to chromosomal

microarrays may facilitate more diagnoses of genetic

diseases.33 Foetal growth restriction was classified

based on birthweight centile; it might have been

underestimated because foetal death might have

occurred several days before birth. Thus, we used

foetal weight below the third centile as a threshold to

identify high-risk cases. Lastly, although our cohort

provides extensive data regarding stillbirths in Hong

Kong, the number of cases may have been insufficient

to identify statistically significant results concerning

less common events. Nonetheless, our findings

provide a basis for future territory-wide reviews

of perinatal outcomes. We will also investigate the

neonatal mortality of singleton pregnancies and

perinatal mortality of multiple pregnancies in our

subsequent studies.

Conclusion

The overall perinatal mortality rate was significantly

reduced from 2000-09 to 2010-19. We observed a

declining trend in stillbirth rate among singleton

pregnancies, mainly because of improvements in

early prenatal diagnosis of congenital malformations

and genetic disorders; this led to increasing

termination of affected pregnancies before 24 weeks.

The prevalence of pre-eclampsia has been rising

because of the increasing maternal age, but the

stillbirth rate among patients with pre-eclampsia

has decreased. Foetal growth restriction of

unknown cause contributes to 16% of all stillbirths;

its prevalence has not changed over time. The

majority of FGR cases were not diagnosed before

birth. Overall, 36% of stillbirths were unexplained,

and they might have involved components of FGR.

Therefore, prenatal FGR detection remains a priority

for our obstetric service.

Author contributions

Concept or design: STK Wong, WT Tse, TY Leung.

Acquisition of data: STK Wong, WT Tse, TY Leung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: STK Wong, WT Tse, DS Sahota.

Drafting of the manuscript: STK Wong, SL Lau, TY Leung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: STK Wong, WT Tse, TY Leung.

Analysis or interpretation of data: STK Wong, WT Tse, DS Sahota.

Drafting of the manuscript: STK Wong, SL Lau, TY Leung.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster

Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Ref CRE 2017.442).

References

1. Hong Kong College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists.

Territory-wide Audit Report 2014. Available from: https://www.hkcog.org.hk/hkcog/Download/Territory-wide_Audit_in_Obstetrics_Gynaecology_2014.pdf. Accessed 11 Feb 2021.

2. Cousens S, Blencowe H, Stanton C, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in

2009 with trends since 1995: a systematic analysis. Lancet

2011;377:1319-30. Crossref

3. World Health Organization. Maternal, newborn, child

and adolescent health. Definition of stillbirths. Available

from: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/epidemiology/stillbirth/en/ Accessed 11 Feb 2021.

4. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, et al. National, regional,

and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with

trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob

Health 2016;4:e98-108.Crossref

5. Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Pattinson R, et al. Stillbirths: Where? When? Why? How to make the data count? Lancet

2011;377:1448-63. Crossref

6. de Bernis L, Kinney MV, Stones W, et al. Stillbirths: ending preventable deaths by 2030. Lancet 2016;387:703-16. Crossref

7. Leung TY, Leung TN, Sahota DS, et al. Trends in maternal obesity and associated risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes in a population of Chinese women. BJOG 2008;115:1529-

37. Crossref

8. Chan SS, Lau AP, To KF, Leung TY, Lau TK, Leung TN. Umbilical cord ulceration as a cause of fetal haemorrhage

and stillbirth. Hong Kong Med J 2008;14:148-51.

9. Lau TK, Li CY. A perinatal audit of stillbirths in a teaching

hospital in Hong Kong. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol

1994;34:416-21. Crossref

10. Goldenberg RL, McClure EM, Bann CM. The relationship

of intrapartum and antepartum stillbirth rates to measures

of obstetric care in developed and developing countries.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2007;86:1303-9. Crossref

11. Leung TY, Chung PW, Rogers MS, Sahota DS, Lao TT,

Chung TK. Urgent Cesarean delivery for fetal bradycardia.

Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:1023-8. Crossref

12. Leung TY, Lao TT. Timing of Caesarean section according to urgency. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol

2013;27:251-67. Crossref

13. Wong L, Tse WT, Lai CY, et al. Bradycardia-to-delivery

interval and fetal outcomes in umbilical cord prolapse.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2021;100:170-7. Crossref

14. Sahota DS, Leung WC, Chan WP, To WW, Lau ET,

Leung TY. Prospective assessment of the Hong Kong

Hospital Authority universal Down syndrome screening

programme. Hong Kong Med J 2013;19:101-8.

15. Sahota DS, Leung TY, Fung TY, Chan LW, Law LW, Lau TK.

Medians and correction of biochemical and ultrasound

markers in Chinese undergoing first trimester screening

for Trisomy 21. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009;33:387-93. Crossref

16. Leung TY, Chan LW, Leung TN, et al. First-trimester combined screening for trisomy 21 in a predominantly

Chinese population. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol

2007;29:14-7. Crossref

17. Cheng Y, Leung WC, Leung TY, et al. Women’s preference

for non-invasive prenatal DNA testing versus chromosomal

microarray after screening for Down syndrome: a

prospective study. BJOG 2018;125:451-9. Crossref

18. Chan YM, Leung WC, Chan WP, Leung TY, Cheng YK, Sahota DS. Women’s uptake of non-invasive DNA testing

following a high-risk screening test for trisomy 21 within

a publicly funded healthcare system: findings from a

retrospective review. Prenat Diagn 2015;35:342-7. Crossref

19. Leung TY, Vogel I, Lau TK, et al. Identification of

submicroscopic chromosomal aberrations in fetuses with

increased nuchal translucency and an apparently normal

karyotype. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011;38:314-9. Crossref

20. Harmon QE, Huang L, Umbach DM, et al. Risk of fetal death with preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:628-35. Crossref

21. Chaemsaithong P, Leung TY, Sahota D, et al. Body

mass index at 11-13 weeks’ gestation and pregnancy

complications in a Southern Chinese population: a

retrospective cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med

2019;32:2056-68. Crossref

22. Chaemsaithong P, Sahota D, Pooh RK, et al. First-trimester

pre-eclampsia biomarker profiles in Asian population:

a multicenter cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol

2020;56:206-14. Crossref

23. Chaemsaithong P, Pooh RK, Zheng M, et al. Prospective

evaluation of screening performance of first-trimester

prediction models for preterm preeclampsia in Asian

population. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:650.e1-16. Crossref

24. Cheng YK, Poon LC, Shennan A, Leung TY, Sahota DS.

Inter-manufacturer comparison of automated

immunoassays for the measurement of soluble FMS-like

tyrosine kinase-1 and placental growth factor. Pregnancy

Hypertens 2019;17:165-71. Crossref

25. Cheng Y, Leung TY, Law LW, Ting YH, Law KM, Sahota DS.

First trimester screening for pre-eclampsia in Chinese

pregnancies: case-control study. BJOG 2018;125:442-9. Crossref

26. Li W, Chung CY, Wang CC, et al. Monochorionic twins

with selective fetal growth restriction: insight from

placental whole transcriptome analysis. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2020;223:749.e1-16. Crossref

27. Meng M, Cheng YK, Wu L, et al. Whole genome miRNA

profiling revealed miR-199a as potential placental

pathogenesis of selective fetal growth restriction in

monochorionic twin pregnancies. Placenta 2020;92:44-53. Crossref

28. Cheng YK, Lu J, Leung TY, Chan YM, Sahota DS.

Prospective assessment of the INTERGROWTH-21

and World Health Organization estimated fetal weight

reference curve. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018;51:792-8. Crossref

29. Cheng Y, Leung TY, Lao T, Chan YM, Sahota DS. Impact

of replacing Chinese ethnicity-specific fetal biometry

charts with the INTERGROWTH-21(st) standard. BJOG

2016;123 Suppl 3:48-55. Crossref

30. Leung TY, Chan LW, Leung TN, Fung TY, Sahota DS,

Lau TK. First trimester maternal serum levels of placental

hormones are independent predictors of second trimester

fetal growth parameters. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol

2006;27:156-61. Crossref

31. Leung TY, Sahota DS, Chan LW, et al. Prediction of birth

weight by crown-rump length and maternal serum levels

of pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A in the first

trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008;31:10-4. Crossref

32. Reinebrant HE, Leisher SH, Coory M, et al. Making

stillbirths visible: a systematic review of globally reported

causes of stillbirth. BJOG 2018;125:212-24. Crossref

33. Hui AS, Chau MH, Chan YM, et al. The role of chromosomal

microarray analysis among fetuses with normal karyotype

and single system anomaly or nonspecific sonographic

findings. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2021;100:235-43. Crossref