© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

COMMENTARY

ICU Liberation for critically ill children in

Hong Kong

A Dudi, MB, BS, FAAP1; KL Hon, MB, BS, MD1; Henry CH Pak, MSc, BSc PT2 Stephen WW Chan, DHSc, MSc2; Cecilia YS Leung, MSc, BSc OT2; Sabina CS Chan, MSc, MA2 CC Au, MB, BS, MRCPCH1

1 Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Allied Health, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Dr CC Au (aucc@ymail.com)

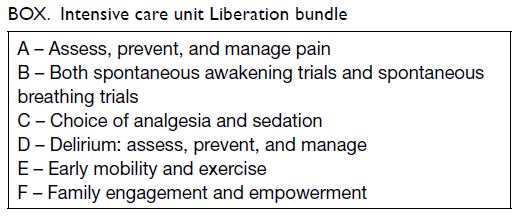

Intensive care unit (ICU) Liberation (https://www.sccm.org/iculiberation) is a campaign to promote

patient recovery by being mindful of reducing

iatrogenic harms during ICU stay, proposed by the

United States Society of Critical Care Medicine.1 2

The ICU Liberation bundle includes the ABCDEF

elements (Box). The ICU Liberation elements have

been broadly adopted in adult intensive care units

and improved outcomes significantly.3 Moreover,

ICU Liberation could be adapted to the needs of

children and their family.4 5 Herein we present our

own experience of adopting and implementing ICU

Liberation practices at a paediatric ICU (PICU) in

Hong Kong.

In the past decade, more patients have survived paediatric intensive care compared with previous

decades.6 This has brought long-term morbidities

among patients discharged from the PICU,

collectively known as post–intensive care syndrome

(PICS) in children.7 8 These long-term morbidities

include functional deficits of physical, cognitive,

emotional, and social health that affect the daily

life, school performance, and social performance

of these patients and their family.9 10 11 The PICS

affects one-third of patients discharged from PICU

and can persist for years.12 The well-intended and

often aggressive treatment in the PICU is, in part,

the origin of PICS in children. The PICU stay is a

physically traumatic and emotionally stressful

experience for children and their family, and these

individuals may develop PICS, such as post-traumatic

stress disorder13 or critical illness myopathy.14 Acute

PICU care prioritise disease control with aggressive

treatment over considerations for sleep, recovery,

and rehabilitation; however, the patient may develop ventilator dependence,15 physical impairment,16 or delirium.17 18

The PICU at Hong Kong Children’s Hospital

commenced service on 27 March 2019. In the first

2 years, the capacity of the PICU grew rapidly from

four beds to 16 beds, with a total of 650 patients

treated. The PICU provides a full range of intensive

care support, including mechanical ventilation,

continuous renal replacement therapy, and

extracorporeal life support. As clinical leaders with

a vision to transform PICU culture in our hospital,

we advocate ICU Liberation in our daily practice.

We have established close collaboration between

medical, nursing, and allied health teams. The PICU

practice has evolved according to consensus and

teamwork.

Our practice is founded on a humanistic

approach. Learning, caring, and smiling are the

core values of the Hong Kong Children’s Hospital.

Education is emphasised to consolidate knowledge

and changes. Individual patient care goals are

regularly discussed by staff during team rounds.

Staff also receive formal on-the-job training as well

as informal feedback, including on pain assessment,

non-pharmacological treatment, and analgesics;

spontaneous awakening and breathing trial in

children; sedation titration to target adequate effect;

environmental modification to promote sleep and

reduce delirium; early mobilisation; and family

empowerment. A clinical information system is

used to document and review individual patient

progress in the ABCDEF elements. Patient outcomes

are audited and long-term follow-up is arranged

for patients with complicated PICU course. For

patients with acute medical conditions, after their

condition is stabilised, they are considered for each

of the ABCDEF elements. We carefully consider

how to proceed, taking necessary precautions and

correcting deviations, to ensure patient safety at

all times. Patient-related factors, such as functional

status, development, and nutrition, are considered

individually. As a result, interventions in our PICU

have progressed towards improving physical,

psychological, and social sequelae.

Through implementing ICU Liberation practices, we have realised several key improvements.

We have been able to actively mobilise patients who

are still receiving mechanical ventilation, continuous

renal replacement therapy, or intracranial pressure

monitoring. We have actively engaged families, even

during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic,

by using communication tools such as digital

photographs and videoconferencing software. We

have facilitated family care even in complex medical

conditions by training caregivers. And we have also

extended family support to palliative care in the

PICU, including home visits. In each case, the ICU

Liberation bundle was carefully considered and

tailored to according to individual assessment.

Barriers to ICU Liberation have been

overcome by leadership and teamwork. Challenges

present were owing to system factors and staff

factors. In our future development we would address

these challenges by developing clinical practice

protocols, coordinating the roles of team members,

and supporting staff knowledge and procedural

competence. We propose focusing in future on

further improvements to treating pain, facilitating

spontaneous breathing, minimising sedation,

preventing delirium, mobilising early, and engaging

family members, in order to better support patient

recovery. Further studies are warranted to evaluate

implementation strategies for ICU Liberation and

perceptions of ICU Liberation in our PICU.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept or design of the study,

acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data, drafting

of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for

important intellectual content. All authors had full access to

the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version

for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and

integrity.

Conflicts of interest

As an editor of the journal, KL Hon was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

1. Ely EW. The ABCDEF Bundle: science and philosophy of how ICU liberation serves patients and families. Crit Care Med 2017;45:321-30. Crossref

2. Marra A, Ely EW, Pandharipande PP, Patel MB. The ABCDEF bundle in critical care. Crit Care Clin

2017;33:225-43. Crossref

3. Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, et al. Caring for critically ill patients with the ABCDEF bundle. Crit Care Med 2019;47:3-14. Crossref

4. Walz A, Canter MO, Betters K. The ICU liberation bundle and strategies for implementation in pediatrics. Curr Pediatr Rep 2020;8:69-78. Crossref

5. Smith HA, Besunder JB, Betters KA, et al. 2022 Society

of critical care medicine clinical practice guidelines

on prevention and management of pain, agitation,

neuromuscular blockade, and delirium in critically

ill pediatric patients with consideration of the ICU

environment and early mobility. Pediatr Crit Care Med

2022;23:e74-110. Crossref

6. Namachivayam P, Shann F, Shekerdemian L, et al. Three

decades of pediatric intensive care: who was admitted,

what happened in intensive care, and what happened

afterward. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010;11:549-55. Crossref

7. Manning JC, Pinto NP, Rennick JE, Colville G, Curley MA.

Conceptualizing post intensive care syndrome in

children—The PICS-p Framework. Pediatr Crit Care Med

2018;19:298-300. Crossref

8. Herrup EA, Wieczorek B, Kudchadkar SR. Characteristics of postintensive care syndrome in survivors of pediatric critical illness: a systematic review. World J Crit Care Med

2017;6:124-34. Crossref

9. Ebrahim S, Singh S, Hutchison JS, et al. Adaptive behavior, functional outcomes, and quality of life outcomes of children requiring urgent ICU admission. Pediatr Crit

Care Med 2013;14:10-8. Crossref

10. Bronner MB, Knoester H, Sol JJ, Bos AP, Heymans HS, Grootenhuis MA. An explorative study on quality of life and psychological and cognitive function in pediatric survivors

of septic shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2009;10:636-42. Crossref

11. Jones S, Rantell K, Stevens K, et al. Outcome at 6 months after admission for pediatric intensive care: a report of a national study of pediatric intensive care units in the United Kingdom. Pediatrics 2006;118:2101-8. Crossref

12. Ong C, Lee JH, Leow MK, Puthucheary ZA. Functional outcomes and physical impairments in pediatric critical care survivors: a scoping review. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016;17:e247-59. Crossref

13. Nelson LP, Gold JI. Posttraumatic stress disorder in

children and their parents following admission to the

pediatric intensive care unit: a review. Pediatr Crit Care

Med 2012;13:338-47. Crossref

14. Kukreti V, Shamim M, Khilnani P. Intensive care unit acquired weakness in children: critical illness

polyneuropathy and myopathy. Indian J Crit Care Med

2014;18:95-101. Crossref

15. Shehabi Y, Bellomo R, Reade MC, et al. Early intensive care sedation predicts long-term mortality in ventilated critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

2012;186:724-31. Crossref

16. Bone MF, Feinglass JM, Goodman DM. Risk factors for acquiring functional and cognitive disabilities during admission to a PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2014;15:640-8. Crossref

17. Smith HA, Gangopadhyay M, Goben CM, et al. Delirium

and benzodiazepines associated with prolonged ICU stay

in critically ill infants and young children. Crit Care Med

2017;45:1427-35. Crossref

18. Smith HA, Fuchs DC, Pandharipande PP, Barr FE, Ely EW.

Delirium: an emerging frontier in the management of

critically ill children. Crit Care Clin 2009;25:593-614. Crossref