© Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Serial surveys of Hong Kong medical students

regarding attitudes towards HIV/AIDS from 2007 to 2017

Greta Tam, MB, BS, MS1; NS Wong, PhD2; SS Lee, MD2

1 Department of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Corresponding author: Prof SS Lee (sslee@cuhk.edu.hk)

Abstract

Introduction: With widespread adoption of

antiretroviral therapy, human immunodeficiency

virus (HIV) epidemiology has changed since the late

2000s. Accordingly, attitudes towards the disease

may also have changed. Because medical students

are future physicians, their attitudes have important

implications in access to care among patients with

HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Here, we performed a survey to compare medical

students’ attitudes towards HIV/AIDS between the

late 2000s (2007-2010) and middle 2010s (2014-2017).

Methods: From 2007 to 2010, we surveyed three

cohorts of medical students at the end of clinical

training to assess their attitudes towards HIV/AIDS.

From 2014 to 2017, we surveyed three additional

cohorts of medical students at the end of clinical

training to compare changes in attitudes towards

HIV/AIDS between the late 2000s and middle 2010s.

Each set of three cohorts was grouped together to

maximise sample size; comparisons were performed

between the 2007-2010 and 2014-2017 cohorts.

Results: From 2007 to 2010, 546 medical students

were surveyed; from 2014 to 2017, 504 students were surveyed. Compared with students in the late 2000s,

significantly fewer students in the mid-2010s initially

encountered patients with HIV during attachment

to an HIV clinic or preferred to avoid work in a field

involving HIV/AIDS; significantly more students

planned to specialise in HIV medicine. Student

willingness to provide HIV care remained similar

over time: approximately 78% of students were

willing to provide care in each grouped cohort.

Conclusion: Although medical students had

more positive attitudes towards HIV/AIDS, their

willingness to provide HIV care did not change

between the late 2000s and middle 2010s.

New knowledge added by this study

- Although medical students had more positive attitudes towards human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), their willingness to provide HIV care in Hong Kong did not change between the late 2000s and middle 2010s.

- Interventions to reduce stigmatising attitudes towards people living with HIV should be incorporated during training for healthcare professionals.

- The medical school curriculum could be updated to incorporate interventions that involve experiential and affective teaching components to adequately address HIV stigma; additional clinical attachments can ensure that medical students have adequate exposure to patients with HIV.

Introduction

Since the beginning of the human immunodeficiency

virus (HIV) epidemic, stigma and discrimination

have affected the provision of healthcare to patients

with HIV. These factors have limited access to HIV

testing and treatment; they have also prevented

the uptake of interventions, such as pre-exposure

prophylaxis.1 The global shift necessary in the

biomedical response to acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome (AIDS) thus heavily relies on reductions of both stigma and discrimination. The importance

of stigma reduction has been recognised as a key

priority in the Blueprint for Achieving an AIDS-Free

Generation (established by The United States

President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief)2 and in

the HIV investment framework (established by The

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS).3

For many years, stigma from healthcare

professionals has remained a major barrier to

access for HIV prevention and treatment services. According to aggregated data from the Stigma

Index for 50 countries, healthcare has been denied

to one in eight people living with HIV (PLHIV).4

Despite high antiretroviral therapy coverage, Hong

Kong is no exception to this phenomenon. In the

early and middle 2010s, 26.8% of PLHIV reported

stigmatising experiences during treatment for non-

HIV-related healthcare needs.5 Since the late 2000s,

advances in HIV treatment have led to a decline in

mortality.6 Increasing life expectancy among PLHIV

has resulted in higher HIV prevalence.7 Thus,

medical students have an increased likelihood of

encountering patients with HIV in future clinical

practice, irrespective of their specialties. Because

HIV epidemiology has changed over the years,

medical students’ attitudes towards the disease

may also have changed. If attitudes have changed,

the medical school curriculum should be adjusted

to match such changes; this will ensure that future

physicians can provide the best possible care. To our

knowledge, no study has compared changes over

time in medical students’ attitudes towards HIV.

Thus, we performed a survey to compare medical

students’ attitudes towards HIV/AIDS between the

late 2000s (2007-2010) and middle 2010s (2014-2017).

Methods

Study design

This study was a descriptive cross-sectional survey to measure medical students’ attitudes towards HIV/AIDS, as well as their experiences within the HIV curriculum.

Sampling

An assessment survey was administered to final-year

medical students at the Chinese University of

Hong Kong, one of the two medical schools in Hong

Kong. Questionnaires were distributed to medical

students at the end of their final-year attachment to

an HIV specialist clinic. At the Chinese University

of Hong Kong, HIV education is an integral part of

the medical student curriculum. Over the course of

3 years, students attend microbiology and medicine

lectures regarding HIV/AIDS, a community

medicine module that includes the prevention and

control of HIV infection, a half-day attachment

to Hong Kong’s largest HIV specialist clinic, and

hospital ward rounds that involve patients with

HIV. The HIV curriculum was generally consistent

between the late 2000s and middle 2010s. This study

was based on the analysis of survey data collected

from six cohorts of medical students: three from

2007 to 2010 and three from 2014 to 2017. All

students were asked to complete the survey during

their final teaching session. Hard copies of the

self-administered structured questionnaire were

distributed to the students and collected by the

course instructors. All responses were anonymous

and participation was voluntary.

Data collection instrument

The study questionnaire was originally developed as

an assessment form by the HIV medicine teaching

team at the Chinese University of Hong Kong; it

was designed for completion by final-year medical

students. The form was piloted in 2005 and became

standardised in 2007, with minor modifications in

subsequent years.8 The questionnaire was in English

and consisted of 25 close-ended questions; all

questions were completed by the students without

assistance. The questionnaire contents slightly

differed between the 2007-2010 and 2014-2017

survey periods. Seven questions that appeared in

both questionnaires were selected for analysis.

These questions focused on demographics, exposure

to patients with HIV, and attitudes towards patients

with HIV. Eight additional questions were analysed

for cohorts from 2014 to 2017. These questions

focused on a participant’s ability to recall various

HIV learning experiences and their satisfaction with

clinical exposure during attachment to an HIV clinic.

We divided students into groups according to their willingness to provide HIV care in the future. An

unwilling student chose “strongly agree” or “agree” (on a four-point scale for cohorts from 2007 to 2010

and a six-point scale for cohorts from 2014 to 2017)

when asked whether they would refuse to perform

treatment or surgical procedures for patients with HIV.

Statistical analysis

We calculated proportions of responses, along

with exact binomial 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

We used bivariable logistic regression to compare

exposure and attitudes between participants in the

2007-2010 cohort (cohorts from 2007 to 2010) and

the 2014-2017 cohort (cohorts from 2014 to 2017);

each set of three cohorts was grouped together

to maximise sample size. Factors associated with

willingness to provide HIV care were analysed

using bivariable logistic regression. SPSS software

(Windows version 26; IBM Corp., Armonk [NY],

United States) was used for data management and

statistical analyses. Two-sided P values <0.05 were

considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

In total, 1050 final-year students participated in the

survey. Three cohorts of final-year medical students

participated between 2007 and 2010 (n=546); three

additional cohorts of final-year medical students

participated between 2014 and 2017 (n=504).

The response rates were 97% in the 2007-2010

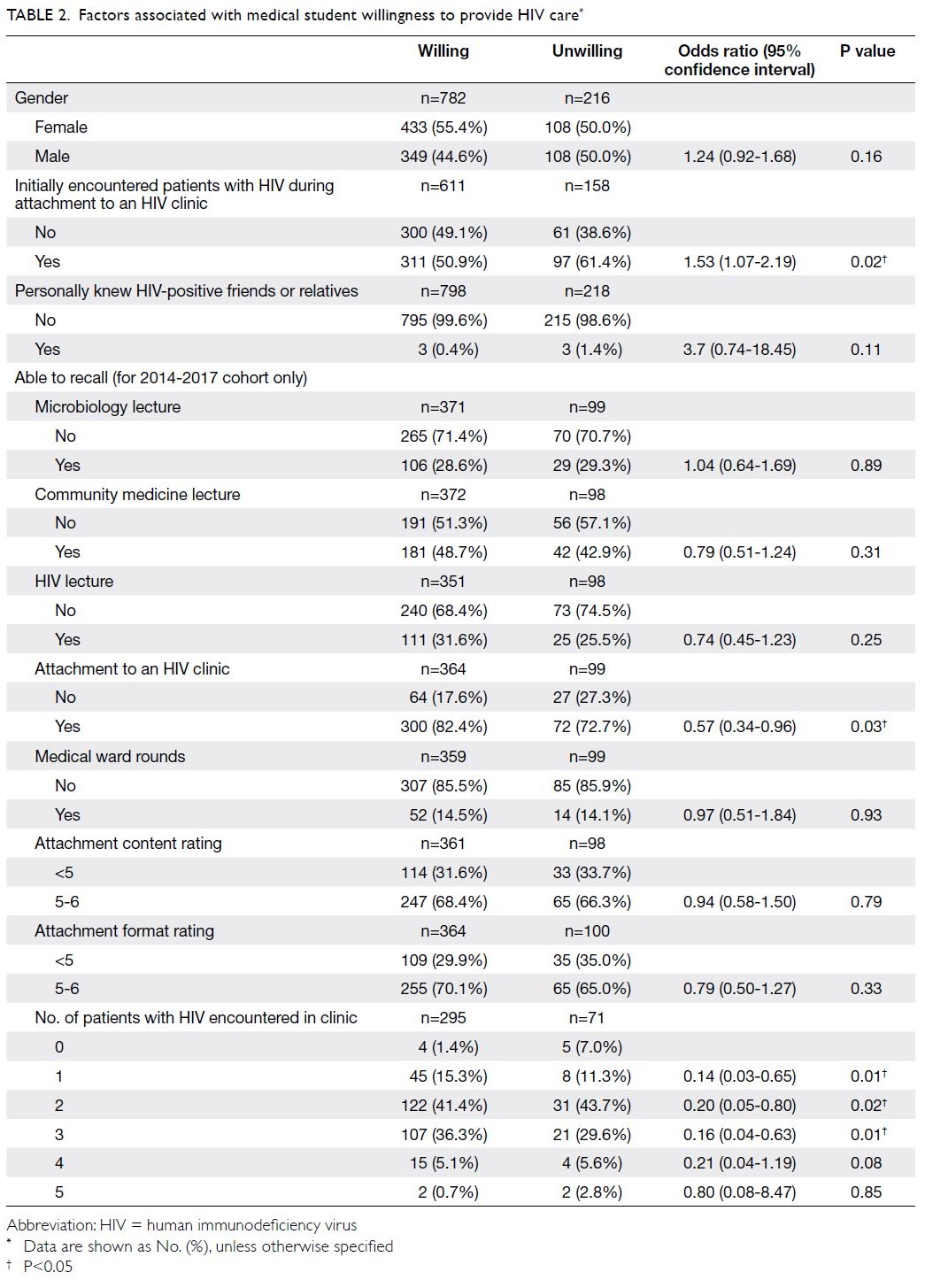

cohort and 91% in the 2014-2017 cohort. Table 1

shows the detailed characteristics, exposure, and

attitudes among the surveyed students. There was

no difference in gender between the 2007-2010

and 2014-2017 cohorts (odds ratio [OR]=1.14; 95%

CI=0.89-1.46).

Table 1. Medical students’ exposure to and attitudes towards patients with HIV: comparison between cohorts

Participant exposure

Significantly fewer students (39.3%) in the mid-2010s initially encountered patients with HIV during

attachment to an HIV clinic, compared with students

in the late 2000s (72.1%; OR=0.25; 95% CI=0.18-0.34)

[Table 1]. The proportion of students who personally

knew HIV-positive friends or relatives remained low and did not significantly differ over time (OR=0.55;

95% CI=0.1-3.01). In the 2007-2010 and 2014-2017

cohorts, only four of 545 students (0.7%) and two of

495 students (0.4%), respectively, personally knew

HIV-positive friends or relatives.

Participant attitudes

Student willingness to provide HIV care was similar between cohorts (Table 1). Approximately 78% of

students were willing to provide care (OR=0.98;

95% CI=0.73-1.33). The proportion of students who

preferred to avoid work in a field involving HIV/AIDS significantly decreased over time: 17.2% in

the 2007-2010 cohort, compared with 10.6% in the

2014-2017 cohort (OR=0.57; 95% CI=0.4-0.83). An

increasing number of students planned to specialise

in clinical HIV treatment: 11 of 517 students (2.1%)

in the 2007-2010 cohort, compared with 53 of 480

students (11%) in the 2014-2017 cohort (OR=5.71;

95% CI=2.95-11.07).

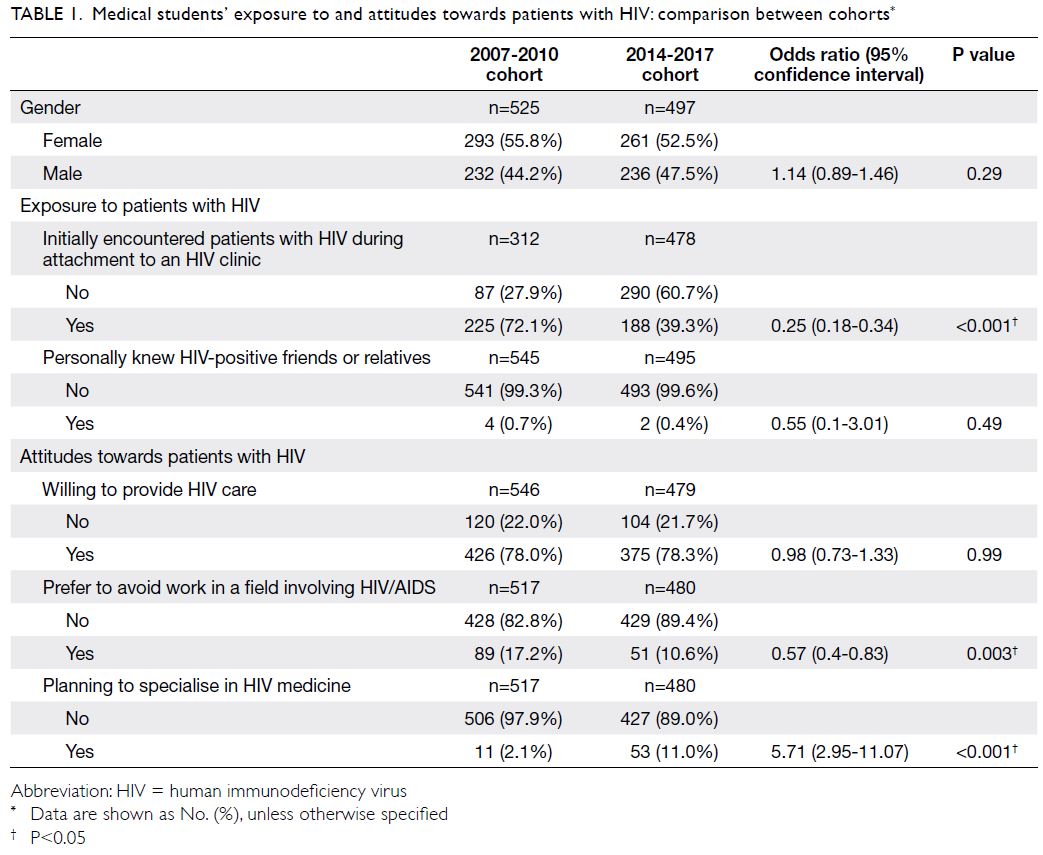

There was no difference in gender between

willing and unwilling students (OR=1.24;

95% CI=0.92-1.68) [Table 2]. Unwilling students were

more likely than willing students to have initially

encountered patients with HIV during attachment

to an HIV clinic (61.4% vs 50.9%) [OR=1.53;

95% CI=1.07-2.19]. Willingness was not associated

with personally knowing HIV-positive friends or

relatives. In the 2014-2017 cohort, most students

(80.3%) recalled their attachment to an HIV

clinic, whereas fewer than half could recall other

components of the HIV curriculum (lectures and

ward rounds; 14.5-48.7%). Notably, the ability to

recall attachment to an HIV clinic was associated

with willingness (OR=0.57; 95% CI=0.34-0.96)

to provide HIV care. Ratings of the content and

format of the attachment to an HIV clinic were not

associated with willingness (OR=0.94; 95% CI=0.58-1.50 and OR=0.79; 95% CI=0.50-1.27, respectively).

Overall, most students (97.5%) have encountered

>1 patient with HIV during clinical attachment.

Unwilling students (5/71, 7%) were less likely than

willing students (4/295, 1.4%) to have encountered

any patients with HIV during clinical attachment.

Discussion

Human immunodeficiency virus prevalence has

risen over time8 with advances in antiretroviral

therapy that contribute to prolonged survival; this

pattern has been observed in nearly all countries,

irrespective of the initial HIV prevalence. Thus,

it is unsurprising that exposure to patients with

HIV/AIDS increased over time among medical

students in our study. Nevertheless, Hong Kong

remains a low prevalence setting for HIV/AIDS9;

therefore, the number of students who personally

knew HIV-positive friends or relatives has remained

low. Despite predictable trends in exposure to patients with HIV since the late 2000s, some students

maintained negative attitudes towards patients with

HIV. Although exposure to patients with HIV has

increased, the proportion of students unwilling to

provide HIV care did not change between the late

2000s and middle 2010s. The proportion of unwilling

students in our study is higher than that in a similar

study conducted in 2011 in Malaysia, where 10% to

15% of students reported unwillingness to provide

HIV care.10 Because medical students are future

healthcare providers, their unwillingness to provide

HIV care represents an extreme manifestation

of stigma, which has been a problem since the

HIV/AIDS epidemic began.11

Stigma can have subtle effects, which may

influence career choices. A previous study found

that these effects can diminish over time12; our

results are consistent with that finding. While a large

proportion of students did not plan to work in a field

involving HIV, such plans may be related to personal

preferences for medical disciplines that facilitate

career development and job opportunities, although

discrimination cannot be ruled out. However, the

present study showed that, over time, fewer students

have reported that they prefer to avoid working in a

field involving HIV/AIDS. Encouragingly, increasing

numbers of students are planning to specialise in

clinical HIV treatment. “Interest” has been most

frequently cited as the main reason for choosing

a specialty; thus, interest in HIV/AIDS may be

increasing among medical students.13 However, the

proportion of students who intended to specialise in

clinical HIV treatment was lower in our study than

in a previous study in the United Kingdom, where

8% to 24% of students reported such an intention.14

Clinical attachment with patient exposure

appears to be an effective learning experience. In the

current system, some students may have overlooked

and missed the opportunity to encounter a patient

with HIV/AIDS. We found that, compared with

willing students, a higher proportion of students

unwilling to provide HIV/AIDS care had not

encountered a patient with HIV/AIDS during their

clinical attachment. This difference may be attributed

to a lack of exposure to patients with HIV/AIDS

during the medical school curriculum. Students

may benefit from repeated exposure to patients with

HIV/AIDS in different settings—willing students

were more likely to have previously encountered a

patient with HIV/AIDS. Further research is needed

to determine whether students could be exposed

to patients with HIV outside clinical settings (eg,

through non-governmental organisations) and to

understand the impacts of such exposure. Willing

students were more likely to recall their attachment

to an HIV clinic, compared with other teaching

methods; this suggests that their emotions were

aroused, which prompted recall.15

Previous research has shown that teaching

methods with experiential, small group, or affective

components and role models of positive attitudes

can effectively change students’ attitudes.14 Such considerations may be useful in clinics where small

numbers of students observe patient management

by a specialist physician. If a student is emotionally

affected by a patient or sees the clinician as a good role model, the clinical attachment may constitute a

memorable experience. This may be more important

than gaining technical knowledge and skills through

the clinical attachment experience because content

and format were not associated with willingness to

provide HIV care. Our results are consistent with

the findings of previous studies, which showed that

frequent clinical exposure to patients with HIV/AIDS

led to more positive attitudes.14 16 17 18 19 20 Furthermore,

knowledge alone cannot effectively decrease HIV

stigma21; similarly, we found that the ability to

recall lectures was not associated with willingness

to provide care for patients with HIV/AIDS.

However, increased exposure alone may be

insufficient to combat HIV stigma. Antibias

information is also needed to reduceprejudice,22

such as homophobia, which has been associated

with unwillingness to provide care for patients with

AIDS.12 Medical training should address these issues

that contribute to stigma towards patients with

HIV/AIDS. Notably, medical students reportedly

demonstrated increased willingness to provide

care for patients with HIV/AIDS after they had

attended an PLHIV sharing session or participated

in experiential games that were designed to increase

empathy towards PLHIV.23 In another study, HIV

stigma levels decreased in medical students after

exposure to an intervention that included discussion

of HIV stigma and other pre-existing related stigmas

(eg, homosexuality and illegal drug use).24

This study had some limitations. First, it was a comparison of cross-sectional surveys over a

10-year period and thus we were unable to assess

potential changes in attitudes among medical

students within a single cohort. Second, each cohort

used in comparative analysis was composed of three

annual cohorts; therefore, time intervals varied

among cohorts (eg, the 2007 and 2017 cohort were

separated by 10 years, whereas the 2010 and 2014

cohorts were separated by 4 years). Nevertheless,

we grouped cohorts together to maximise sample

size; our analysis clearly showed changes in attitudes

among medical students over time.

Conclusions

Despite more positive attitudes towards HIV/AIDS in terms of career choices, the willingness of medical

students to provide HIV care did not change between

the late 2000s and middle 2010s.

Interventions to reduce stigmatising attitudes

among towards PLHIV should be incorporated

in medical training; however, the framework for

medical school curriculum in Hong Kong makes

no mention of such interventions, although it

lists “attitudes and professionalism” as a core

competency.25 The medical school curriculum could

be updated to incorporate interventions that involve

experiential and affective teaching components to adequately address HIV stigma; additional clinical

attachments can ensure that medical students have

adequate exposure to patients with HIV.

Author contributions

Concept or design: G Tam, SS Lee.

Acquisition of data: SS Lee.

Analysis or interpretation of data: NS Wong.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Acquisition of data: SS Lee.

Analysis or interpretation of data: NS Wong.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Survey and Behavioural

Research Ethics Committee, The Chinese University of Hong

Kong (Ref 12-01-2011). Participation was voluntary and

completion of the survey implied consent to participate in the

study. All data were anonymised and confidential.

References

1. Stangl AL, Lloyd JK, Brady LM, Holland CE, Baral S. A

systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related

stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have

we come? J Int AIDS Soc 2013;16(3 Suppl 2):18734. Crossref

2. US Department of State. The United States President’s

emergency plan for AIDS relief. Available from: https://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/201386.pdf.

Accessed 7 Jun 2022.

3. Schwartländer B, Stover J, Hallett T, et al. Towards an improved investment approach for an effective response to HIV/AIDS. Lancet 2011;377:2031-41. Crossref

4. International Health Policy Program (IHPP), Ministry

of Public Health, Thailand. Report of a Pilot: Developing

Tools and Methods to Measure HIV-related Stigma and

Discrimination in Health Care Settings in Thailand.

Thailand: IHPP, Ministry of Public Health; 2014.

5. Scientific Committee on AIDS and STI (SCAS) Centre for

Health Protection Department of Health. Recommended

principles and practice of HIV clinical care in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong, 2016. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/static/24003.html. Accessed 8 Jun 2022

6. The Lancet. The global HIV/AIDS epidemic—progress and

challenges. Lancet 2017;390:333. Crossref

7. Fettig J, Swaminathan M, Murrill CS, Kaplan JE. Global epidemiology of HIV. Infect Dis Clin North Am

2014;28:323-37. Crossref

8. Lee SS, Lam A, Lee KC. How prepared are our future doctors for HIV/AIDS? Public Health 2012;126:165-7. Crossref

9. Virtual AIDS Office of Hong Kong. HIV/AIDS Statistics in

Hong Kong 1984-June 2020. Available from: http://www.info.gov.hk/aids/english/surveillance/cumhivaids.jpg.

Accessed 8 Jun 2022.

10. Ahmed SI, Hassali MA, Bukhari NI, Sulaiman SA. A

comparison of HIV/AIDS related knowledge, attitudes and

risk perceptions between final year medical and pharmacy

students: a cross sectional study. Healthmed 2011;5:317-25.

11. Radecki S, Shapiro J, Thrupp LD, Gandhi SM, Sangha SS,

Miller RB. Willingness to treat HIV-positive patients at

different stages of medical education and experience. AIDS

Patient Care STDS 1999;13:403-14. Crossref

12. Kopacz DR, Grossman LS, Klamen DL. Medical students

and AIDS: knowledge, attitudes and implications for

education. Health Educ Res 1999;14:1-6. Crossref

13. Wu SM, Chu TK, Chan ML, Liang J, Chen JY, Wong SY. A

study on what influence medical undergraduates in Hong

Kong to choose family medicine as a career. Hong Kong

Pract 2014;36:123-9.

14. Ivens D, Sabin C. Medical student attitudes towards HIV.

Int J STD AIDS 2006;17:513-6. Crossref

15. Storbeck J, Clore GL. Affective arousal as information:

how affective arousal influences judgments, learning, and

memory. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2008;2:1824-43. Crossref

16. Syed IA, Hassali MA, Khan TM. General knowledge &

attitudes towards AIDS among final year medical and

pharmacy students. Folia Medica 2010;45:9-13.

17. Mohsin S, Nayak S, Mandaviya V. Medical students’

knowledge and attitudes related to HIV/AIDS. Natl J

Community Med 2010;1:146-9.

18. Tešić V, Kolarić B, Begovac J. Attitudes towards HIV/AIDS among four year medical students at the University of Zagreb Medical School—better in 2002 than in 1993 but

still unfavorable. Coll Antropol 2006;30:89-97.

19. Sanchez NF, Rabatin J, Sanchez JP, Hubbard S, Kalet A.

Medical students’ ability to care for lesbian, gay, bisexual,

and transgendered patients. Fam Med 2006;38:21-7.

20. Umeh CN, Essien EJ, Ezedinachi EN, Ross MW. Knowledge,

beliefs and attitudes about HIV/AIDS-related issues, and

the sources of knowledge among health care professionals

in southern Nigeria. J R Soc Promot Health 2008;128:233-9. Crossref

21. Liu X, Erasmus V, Wu Q, Richardus JH. Behavioral

and psychosocial interventions for HIV prevention in

floating populations in China over the past decade: a

systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PLoS One

2014;9:e101006. Crossref

22. Aboud FE, Tredoux C, Tropp LR, Brown CS, Niens U,

Noor NM, Una Global Evaluation Group. Interventions

to reduce prejudice and enhance inclusion and respect for

ethnic differences in early childhood: a systematic review.

Dev Rev 2012;32:307-36. Crossref

23. Mak WW, Cheng SS, Law RW, Cheng WW, Chan F.

Reducing HIV-related stigma among health-care

professionals: a game-based experiential approach. AIDS

Care 2015;27:855-9. Crossref

24. Varas-Díaz N, Neilands TB, Cintrón-Bou F, et al. Testing

the efficacy of an HIV stigma reduction intervention with

medical students in Puerto Rico: the SPACES project. J Int

AIDS Soc 2013;16(3 Suppl 2):18670. Crossref

25. The Medical Council of Hong Kong. Hong Kong doctors.

2017. Available from: https://www.mchk.org.hk/english/publications/files/HKDoctors.pdf. Accessed 8 Jun 2022.